Читать книгу Cumberland - Megan Gannon - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеNine

Izzy’s temperature is back up to 101˚ but she’s clear-eyed, intent on her books, and she doesn’t take her eyes from the pages as she opens her mouth for me to drop in the aspirin and tilt a glass to her lips. The house is dark with late-afternoon shadow when I go downstairs for the sewing scissors Grand keeps in the cabinets behind the kitchen table. I shove past all the old bills and lists and table linens so ancient they’re stiff along their creases to pull out the sewing kit. Putting everything back, I notice a stack of ragged-lipped envelopes rubber-banded together, all addressed to Grand with a return address from Carson & Carson Contractors. One of the envelopes has the postmark date June 3, 1974—only a month old, and the memory of Mrs. Jorgen and Mrs. Sibley saying something about the Carson brothers and money nudges me.

I slide the top envelope out from under the rubber band and peek inside. There’s half a piece of watermarked green paper with a ragged perforation across the bottom. At the top it reads “Group term policy for John Mackenzie” and under that “Death benefits paid in the form of annuity” with the date 5/1/74—5/30/74. Next to that is the number 543.56. I pull out another envelope and this one reads 4/1/74—4/31/74 and next to it again, 543.56. They’re both signed neatly at the bottom, Carl Carson. I read the words over and over but whatever I’m supposed to catch hovers just above me.

The couch creaks in the other room and I shove all the envelopes back, stacking them in front of some manila folders puffy with crinkled pages and labeled “Medical—John,” “Medical—Ansel” and “Medical—Isabel.” I shift the phonebook back into place and peek into the den. Grand’s still parked in front of the TV, so I go back and flip open the phonebook to the L’s. I try “Lloyd” and “Loid” and anything else even close, but there isn’t a listing in Cumberland and I wonder what Everett’s grandfather does to have an unlisted number. I stand at the sink window where the day’s grown sharp with shadows and imagine walking barefoot all the way into town, finding his grandparents’ house, tapping on the window… and then what.

Izzy’s propped up in the desk intent on the art book, and when I come back in with the scissors she reaches for her notepad.

Canvas, she writes. How big is it?

“You mean for painting? It comes in all sizes, I think. My art teacher last year showed us these drippy pictures that were so big they wouldn’t fit in this room.”

She outlines the shape of the window in the air with her finger then writes me out a shopping list. Tube acrylics: indigo viridian cadmium onyx violet white and any in-between blues and greens. And grey spelled ey not ay.

“Your wish is my command, mademoiselle,” I say, thinking there’s no way Grand will give me money for all of that. “Now if you’ll just hold still, I’ll have this wretched hobo disguise off of you in a jiffy.”

I straighten Izzy’s head, measuring her hair out with my fingers, looking for the shortest section to go by. Last summer tending Izzy’s hair got to be too much, so Grand had me crop it down short, and now the pieces hang in chunks like one of the cubist paintings Izzy’s poring over. I wet the brush in the sink until her hair’s all flat and damp, then hold strips of hair between my fingers and snip, the scissors’ sharpness kissing the sides of my fingers. When I’m done Izzy’s hair looks fuller, almost bouncy, curled under at her chin and tidy as a sailor on a box of salt.

After I make dinner, change Izzy’s sheets, take her temperature and tuck her in for the night, I take a deep breath and bring Grand a glass of ice water. Dressed in a filmy sea-green nightgown and matching robe, she sits on the edge of her unmade bed rolling her hair on small plastic rollers, her dingy pink terrycloth slippers dangling from her toes. When I set the water glass on her bedside table she smiles thinly and gives me a little nod of dismissal.

“Grand, I really think Izzy needs a doctor.”

She holds up a hand mirror to check her curlers and doesn’t meet my eye. “Haven’t you been taking care of her?”

“Yes, I’ve been trying, but she’s been running a fever for two days and I think—”

“Give her some aspirin.”

“I’ve been giving her aspirin, but it’s only brought her temperature down to 100˚.”

Grand reaches for another curler and starts to roll the last strand of hair over her left ear. “That isn’t very high,” she says. “I’m sure she’ll be fine.”

I sigh, and Grand’s flat gaze flicks to my face as her mouth purses. “What did you say?”

“Nothing.” She stares at me hard and I can feel her inhaling, dark clouds shifting and settling across her brow. My voice is small in the gathering silence. “I didn’t say anything.”

Grand smacks the roller down on the bed, the last strand of her hair sticking out in a grey tuft, and snatches me by the arm. “It’s hard enough raising two girls without being made to feel guilty all the time,” she says, her mouth trembling. “I live on a fixed income. I can’t indulge every little whim that flits into your heads.”

“This isn’t—” I say, and Grand shakes me, cuts me off.

“You want new clothes. Isabel wants to be waited on hand and foot. Well, we all want something. Do you think I want to make myself sick with worry, alone with you two in this house all day long?” She spits the words at me, the dark cinders of her eyes red-rimmed and watery. “I do all that I can for you girls—all that I can—but it’s not enough, it’s never enough.” She drops my arm and bolts to her feet, bumps into me, and shuffles towards the bathroom. She stops and half turns so I can hear her words. “I should have just let them take you.”

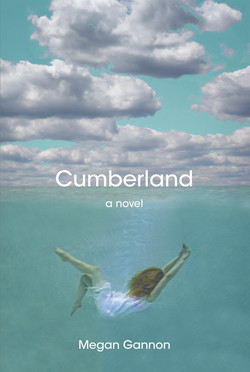

I drop my eyes and back out of the room, my breath coming quick and short as I shut the door behind me, then climb upstairs and don’t meet Izzy’s gaze. I lie on my bed in the dark, listening to her breathing deepen and lengthen, her sighs just out of sync with high tide, then shut my eyes and crowd out Grand’s dark, pinhole eyes with images of Everett’s thin, tendony forearms, Everett standing over his bike, Everett’s hairy, gangly legs. I dream Everett’s eyes, dream them closer and closer until I’m swimming in blue water laced with slants of white sunlight, sinking deeper and deeper with no need for air.

What goes on outside these walls that brings her back to me, gasping, teetering towards tears? This whatever-it-is shouldn’t be her worry. The whole world, and its whirled versions, and how to reel them all into this hive of old wallpaper, everything that could be something to me—which books, which pictures—how could she know? The connection severed, she can’t know what I light towards anymore than I can know who this is she’s lit with. The little tear that pulled apart the accordioned paper dolls. Now they’re two. So you can’t tell which one took the scissors first.

Izzy’s breath is measured, her body slack and tangled in the white sheets. Going downstairs, I’m careful to step over the noisy third step and squeeze through the back door before it can open far enough to squeak. The trees are creaking with frogs and crickets and the moon’s so bright I don’t need a light, just follow the faint glimmer of white sand into town.

When I get to Red’s garage I take a right on Cayman Street and realize, walking past the chain-linked yards and tattered screened-in porches, that I still don’t know where his house is. What was I thinking? That somehow I’d just sleepwalk there? That something would pull me through the streets, hypnotized, and I’d magically find Everett’s grandparents’ house and he’d be waiting?

There’s a light on in a house at the end of the street where an old man sits in his undershirt in front of the TV’s blue flicker. I turn back towards town, cross Main Street, walk along the dark windows of the stores and take a left onto Hill Street towards the blurry sounds of a jukebox, the red glow of a sign reading Watering Hole. Someone laughs, a ball cracks, and the voices are muddy and sluggish, slipping over each other like fat eels. I turn back around and catch out of the corner of my eye a red jeep with a New York plate. The Yankee. I duck under the awning of a store so I’m in shadow and watch two men standing across the street outside the bar’s open door, bottles held loosely in their hands.

“I don’t suppose,” one says, taking his hat off, smoothing his hair, and putting it back on.

“I wouldn’t know the first thing about one of them kind of women.”

“You and me makes two.” He chuckles, sticks out his lower lip, tilts the bottle, and takes a long swig. “Might be worth a look-see. You think?”

“You’re trouble, you know that? What was it my mama told me the first time you brought your scraggy ass around with a fishing pole and a can of crawdads?”

“Trouble had herself a litter and here comes the runt.” They’re laughing, and their laughter has too much air behind it and is too loud. “Must be why I’m always looking for something to suckle on.”

“Oh, no. No, you don’t.” The friend of the man in the hat laughs again, leaning against the wall beside the door, then slips a little and falls in a squat against the building.

“Get up, you drunk.”

“Just leave me be.”

“Get up so you can see how I saunter in there and sweep that damn Yankee off her barstool.” The man in the hat puts his bottle down on the sidewalk and tucks his shirt in, jiggling his belt buckle.

“You’d need one bitch of a broom to sweep her anywhere.”

“Come on, you drunk fuck.”

“I’m coming.” The friend grabs the elbow of the man in the hat and puts his hand out on the wall to steady himself. Then he sticks one foot through the threshold of the bar and puts it down carefully like a toddler stepping onto a boat bobbing against a dock.

I slide down to sit on the sidewalk and pull my t-shirt over my knees. Even across the street the smell seeping out the door is of stale pee and rusty beer cans. The jukebox sounds like it’s under water and a woman in a halter-top walks past the door carrying an empty tray, stuffing bills in her apron. Laughter, and the low murmur of voices.

After a while she comes out—Lee, the woman from the beach. In cargo shorts and a green tank top, she doesn’t look like she’s dressed for a bar. Her hair’s in a messy bun and her camera strap is slung diagonally across her chest like a line of ammo, camera bumping at her hip. She’s walking fast, but not like she’s scared. The man in the hat comes out after her.

“You are never gonna get an opportunity like this again, you know that?”

“Oh, Rusty, I bet you say that to all the girls.” She doesn’t turn around as she talks, taking her keys out of her pocket and walking up to the dusty jeep.

“These things we got around here? You can’t call them girls.” He sidles up behind her and drapes one arm on the window frame, pushes his hat back with his fist. “Not even women. They’re just bitches.” He puts a finger out to touch her bare shoulder and she fits her key in the door, opens it, swings inside and slams it before he can even get his hand back out of the air.

“Well, I’d hate to think what that makes me,” she says, turning the key in the ignition and popping the jeep in reverse. She flashes him a smile that has a little too much teeth then backs up even with the awning I’m crouched under, brakes, and looks at me. “Ansel, right? —Not after the photographer.”

“Yeah.” I stand up and realize it’s pretty cold and the man in the hat is turning to walk back towards the jeep.

She’s looking at me with something like laughter in her eyes, but there’s an edge to her voice. “If I were you, I’d get in.”

“Yeah. Okay.” I hustle around to the passenger side and jump in just as the man in the hat makes it to the jeep and Lee floors it. In the rear view mirror the man in the hat stands there, his hands hanging limply at his sides, then spits and heads back towards the bar.

“It’s none of my business,” she says, glancing at me, one wrist draped over the top of the steering wheel, “But I wouldn’t be out alone in this part of town so late if I were you.” I watch the dust blow up around the jeep and take my time responding since something in her tone rankles me.

“Except you were out alone in this part of town.”

“Right. But I’m not you.”

“Well, I was looking for someone.” She shifts in her seat, pulling her camera around onto her lap, and glances at me again.

“How old are you?”

“Almost sixteen.” I’m trying to sound cool but then I realize what a baby I sound like to be rounding up my age.

“Well, I hope to God whoever you were looking for wasn’t back there.”

“No. I just got lost. Sort of. I was looking for a house.”

“What’s the address?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, what’s it look like?”

“I don’t know.”

Lee lets out a quick “ha!” and leans over to tune the radio wavering between frequencies. She rolls the knob until she finds an oldies station and then pulls the rubber band out of her messy bun, shaking out her dark hair. “You don’t know what it looks like? The CIA must be recruiting you already.”

I think about the list of skills I’d bring to espionage—cereal making, butt wiping, hair brushing—and I can’t help laughing too. “Yeah. Actually, that’s what I was doing back there at the bar. Spying, you know. ”

“So that whole curled-up-in-the-fetal-position-like-an-abused-puppy thing was just part of your cover?”

“Right.”

“Good cover.”

“Thanks.”

She’s nice-looking in a skinny, unkempt kind of way. Except for a long, horsey nose, her features are generic as a china-doll’s, so balanced and symmetrical they might be pretty if she made an effort, but since she doesn’t wear make-up she just looks washed out and plain. Now, with her brown hair down, her plainness is messy enough to seem a little wild, the lines of her cheekbones angling into her small, bow-shaped mouth. The tiniest spark of jealousy simmers in my gut. I look in the rearview mirror and try to imagine my pointy chin, wide forehead, and light-lashed eyes as capable of that kind of fierceness, but I can’t see it. I slouch in the seat and fold my arms.

“It’s a nice night. I could drive up and down some of these sleepy little streets and you could give a shout if you see the house. The, uh, mystery house.” She grins at me.

“Yeah, okay.” We don’t talk, but the radio is tuned to the kind of music I imagine my parents used to listen to, bobby socks and hair pomade music. I shut my eyes and try to imagine what it felt like to have a reason to touch a boy, to put your hand on the hard curve of his shoulder and feel his arm nestle in against your back, his breath up close. His breath in your hair.

“Shouldn’t take long to drive a town that’s, what, eight blocks long and five wide?” She glances at me, and I shrug.

“I’ve never counted.” I try to imagine what a city is like, what New York City is like, and how long it would take to walk from one end to the other. I bet she knows.

“So, do we have anything to go on?” she asks.

“A bike. Probably the only one in town, if he parks it out front.”

Lee nods and smiles sideways at me, a knowing glint in her dark eyes. Although it’s been years since Cumberland had more than a dusting of late-January snow, all the houses look like they’ve emerged from a hard winter, the sea air bleaching them tired and wind-scoured. Each street we drive down, a dog barks somewhere inside.

“There.” Everett’s bike leans against the front porch of a yellow house with a tidy lawn. The windows are dark, but I worry if he looks outside he’ll see me craning forward in the seat of the jeep. When Lee slows down, I slouch low, waving her on, and she laughs and guns the engine.

“You get the house number, Ace?”

“316.”

“Right. Willow Street. Commit it to memory. Agents don’t leave a paper trail.”