Читать книгу The Harpy - Megan Hunter - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление10

The rest of the weekend passed in a haze of routine. I was struck by how easy it was to barely speak to Jake, let alone touch him. Sunday was slow, its minutes thick and draining, the children grumpy and unsettled by its end. But by Monday something had changed. We were quicker in our movements, it seemed, as though the backing track of our lives had been moved up tempo, into some other realm, a fast-forward reality.

The memory of Saturday night was still strong, raising my stomach as I spooned coffee into a glass jug, infusing the grounds with its flavour. I poured hot water from the kettle, seeing again the way Jake had looked at me, for a second, as though he had never seen me before. In that moment, we were strangers again. We had not slept beside each other, over and over, thousands of times. He had not watched me give birth to his children.

The Jake of Saturday was, it seemed, an entirely different man to the one who sat at the kitchen table in the Monday sun, his hair filled with light, flattened on one side from the sofa bed. He was making silly faces at the boys, getting Ted to eat an extra three bites of cereal. Paddy found him hilarious, was howling, rocking back and forth on his chair until Jake switched to serious mode, told him to stop rocking, to sit up straight.

I had always observed this as a kind of wonder: the way Jake knew how to pretend to be normal in front of the children. It was something my parents never managed; every dispute was aired completely openly, as though they had never been told that this was bad for children. As I grew up, I used to wonder whether, in fact, they had some liberal idea that children should be exposed to everything, for the strengthening of their minds or souls. Later on, I realized that there was no theory or plan at all: that was just the way they were.

There were some similarities between then and now, some taste of the past in the air. I remembered how energetic my parents often were, after an argument. How our house seemed to be on its own trajectory, moving more quickly than the rest of the planet, making me wonder how we were all still attached to the ground.

I’d always suspected that, after they made up, the arguments disappeared from their minds, dissolved as though they’d never taken place. But for me, the fights came back constantly: under doorways, through the paper of books I read, a weakening smell. To be around their aggression was one thing, but to not be around it was worse: jumping at noises, forever having strange fears, of fairground rides, loud building work, dogs.

Today, for us, there was no routine farewell, no kiss goodbye. Even Jake, the expert in normality, couldn’t manage it. He waved instead, while turning around, no eye contact. From the door, I watched him take off with the boys, his hand wrapped around the school bags they refused to carry, his voice marshalling them to cross the road. He was wearing a thick coat, a knitted hat. Under his coat, a good jumper his mother had given him. Under that, a cotton shirt: off-white, blue stripes. Under that, I knew, was the scratch: even paler now, peach-coloured, the skin already beginning to close over it, to regrow.

Jake would have known the proper terms for the healing: he could name it exactly. He had a scientific mind, was a biologist by profession; he studied bees, would bring home the tiniest fragments of his work, facts dangled on sticks, things I could understand. Apparently, he told me once, the name Queen Bee is misleading: she doesn’t control the hive, her sole function is to serve as the reproducer. But over this, she has almost perfect control.

~

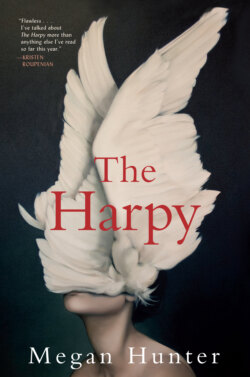

At school, the teachers asked why I always drew her: the woman with wings, her hair long, her belly distended. Is she a bird, they asked me? Is she a witch? I shook my head, refused to tell them anything.

I never shared her with my friends, never named her in our games. I kept her inside me, at the edges of my vision, moving in and out of sight.

~