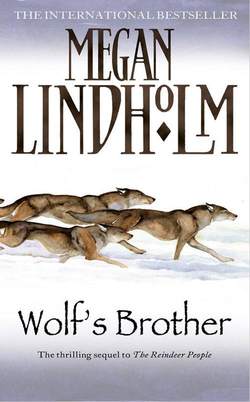

Читать книгу Wolf’s Brother - Megan Lindholm - Страница 6

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеTHE YEAR AFTER Capiam became herdlord, he had torn down his old hut and put up a larger one. It was done, he said, so that his folk might gather comfortably in his hut and tell him the things they were thinking. Bror had snickered that it was actually to accommodate his wife’s growing girth. Remembering Ketla’s outrage and Bror’s bruises, Heckram grinned briefly. He lifted the doorskin from the low door. Carp preceded him.

Earlier Carp had dismissed Heckram from his own hut, saying that he must prepare for his meeting with Capiam, with rituals the uninitiated could not watch. Disgruntled, he had taken refuge with Ibb and Bror, and spent the early evening helping Bror deliver a calf. The calving had gone well, and Heckram had returned feeling optimistic.

He had washed the blood and clinging membranes from his hands and wrists, trying to ignore the smell of scorched hair and burnt herbs that had permeated his hut. Carp had been sitting cross-legged before his hearth, once more clad in his garments of snowy white fox furs. Strings of rattles made of leather and bone draped his wrists and ankles. He wore a necklace of thin black ermine tails alternated with bear teeth. He had not spoken a word to Heckram, but had risen with soft rattlings when he suggested that they go to the herdlord.

And now he entered the herdlord’s hut just as wordlessly as he had left Heckram’s. Heckram stepped in behind him and let the door-hide fall. He set his back teeth at the sight that greeted him. He had requested time with the herdlord, not a hearing of the elders. Yet, in addition to Capiam and his family, there were Pirtsi, Acor, Ristor, and of course, Joboam. Men richer in reindeer than in wisdom, Heckram told himself. But Carp detected nothing wrong. He advanced without waiting to be greeted, and seated himself at the arran without an invitation. Once ensconced, he let his filmed eyes rove over the gathered folk.

“It is good that you have gathered to hear me.” Carp began without preamble. Capiam shifted in surprise at this assumption of control, and Joboam scowled. Carp took no notice. “The herdfolk of Capiam are a people in sore need of a shaman. A najd, I believe you say. I have walked today through your camp. The spirits of the earth cry out in outrage at your carelessness toward them.” He let his eyes move over them accusingly. His gnarled hand caught up the rattles that dangled from his wrist, and he began to shake them rhythmically as he spoke. The fine seeds whispered angrily within the pouches of stiff leather.

“Huts are raised with no regard to the earth spirits. Children are born and no one offers gifts or begs protection. Wolves are hunted, and no offering given to Wolf himself. Bear mutters in his den of your disrespect and Reindeer grows coldly angry. A great evil hovers over your folk, and you are blind to it. But I have come. I will help you.”

There was a white movement in the still room as Kari, the herdlord’s daughter, fluttered from her corner. She flitted closer to the najd and the fire that moved before him. Heckram caught the flash of her bird-bright eyes as she settled again. Avidity filled the gaze she fixed on Carp. No one else seemed to notice her interest.

“Spirits of water and tree are complaining that you use them and make no sign of respect. Reindeer himself has been most generous to you, but you ignore him. How long have you taken his gifts, and made no thanks to him?”

Carp’s rattles sizzled as he turned his gaze from one person to the next. Ketla was white-faced, Kari rapt, Acor and Ristor uneasy. Pirtsi picked at his ear, while Joboam looked sullenly angry. Rolke was bored. Capiam alone looked thoughtful, as if weighing Carp’s words.

“The herdfolk do not turn the najd away,” he said carefully. “But—” The sharp word caught everyone’s attention. “Neither do we cower in fear. You say the spirits are angry with us. We see no sign of this. Our reindeer are healthy, our children prosper. It has been long since we had a najd, but we keep our fathers’ customs. You are not herdfolk, nor a najd of the herdfolk. How can you say what pleases the spirits of our world?”

Acor nodded slowly with Capiam’s words, while Joboam stood with a satisfied smile. He crossed his arms on his chest, his gaze on Heckram. He nodded slowly at him. It had gone his way. But Carp was nodding, too, and smiling his gap-toothed smile.

“I see, I see.” The rattles hissed as he warmed his hands over the fire. Abruptly he stopped shaking them. The cessation of the monotonous noise was startling. He rubbed his knobby hands over the flames, nodding as he warmed them. “You are a happy folk; you have no need of a shaman. You think to yourselves, what need have we of Carp? What will he do? Why, only shake his rattles and burn his offerings and stare into the fire. He will eat our best meat, ask for a share of our huntings and weavings and workings.” Carp leaned forward to peer deep into the fire as he spoke. “Like a dog too old to hunt, he will lie in the sun and grow fat. Let him find another folk to serve. We are content. We do not wish to know…to know…”

His voice fell softer and softer as he spoke. The flames of the fire suddenly shot up in a roar of green and blue sparks. Ketla screamed. The men leaped to their feet and retreated from the blaze. It startled everyone in the tent, except Carp, who moved not at all. The fountaining of sparks singed his hair and eyebrows. The stench of burning hair filled the hut. Thin spirals of smoke rose from his clothes as sparks burned their way down through the fur. He swayed slightly, still staring into the reaching flames. “Elsa?” he asked, his voice high and strange. Everyone gasped. Heckram stopped breathing. “Elsa-sa-sa-sa!” The najd’s voice went higher with every syllable. “The calves are still! The mothers cry for them to rise and follow, but their long legs are folded, the muzzles clogged with their birth sacs. Elsa-saa-saa-saa-saa-saa-saa!”

His voice went on and on, his rattles echoing the sibilant cry. As suddenly as the flames had leaped up they fell, and returned to burning with their familiar cracklings. The najd’s head drooped onto his chest in a silence as sudden as death.

“Elsa! He saw Elsa!” Kari’s shrill cry cracked the silence. Acor and Ristor leaned to mutter at Capiam. Ketla sank slowly to the floor, the back of her hand blocking her gaping mouth. Every hair on Heckram’s body was a-prickle with dread. He swallowed bitterness in a throat gone dry and felt an icy chill up his back. It took him a moment to realize it had an earthly source. The unfastened door-hide flapped in a new wind from the north. Heckram pegged it down. Straightening, he noticed another interesting thing. Joboam was missing.

“Najd! What did you see in the flames?” Capiam demanded.

Carp lifted his head smoothly. “See? Why, nothing. Nothing at all. A happy and contented folk like yours, what do they care what an old man sees in a fire? Just smoke and ash, wood and flame, that’s all a fire is. Heckram, I am weary. Will you grant this old beggar a place in your tent for one night?”

His answer was drowned by Capiam’s raised voice. “The herdlord gladly offers you shelter this night, Carp. But certainly it will be for more than just one night?”

“No, no. Just for a night or two, for an old man to rest from his travels. Then I shall take my apprentice and move on. I will stay at Heckram’s hut. It’s a very large hut, for one man alone. A shame he has no wife to share it. Have you never thought of taking a woman, Heckram?” The old man asked innocently.

“Not since Elsa died!” Kari shrilled out. She flitted over to Carp, her loose garments flapping as she moved. She crouched beside him, her dark eyes enormous. “What did you see in the flames?” she asked in a husky whisper.

“Kari!” her father rebuked her, but she did not heed him. She peered into Carp’s clouded eyes, her head cocked and her lips pursed. For a long moment their gaze held. Then she gave a giggle that had no humor in it and leaped to her feet. She turned to fix her eyes on Pirtsi. Her face was strange, unreadable. Even Pirtsi, immune to subtlety, shifted his feet and scratched the nape of his neck uneasily.

“Heckram and I will leave now!” Carp announced, rising abruptly. He took a staggering step, then gripped the young man’s shoulder and pulled himself up straight.

“But I wished to speak to Capiam, about Kerlew,” Heckram reminded him softly.

Carp’s eyes were icy and cold as gray slush. “Kerlew is my apprentice. His well-being is in my care. He is not for you to worry about. Do you doubt it?”

Heckram met his gaze, then shook his head slowly.

“Good night, Capiam.” Carp’s farewell was bland. “Sleep well and contentedly, as should a leader of a contented folk. Take me to our hut, Heckram. This foolish old man is weary.”

A north wind was slicing through the talvsit. Icy flakes of crystalline snow rode it, cutting into Heckram’s face. It was more like the teeth of winter than the balmy breath of spring. Heckram bowed his head and guided the staggering najd toward his hut. The talvsit dogs were curled in round huddles before their owners’ doors. Snow coated their fur and rimed their muzzles. Heckram shivered in the late storm and narrowed his eyes against the wind’s blast. In a lull of the wind came the lowing cry of a vaja calling her calf. A shiver ran up Heckram’s spine, not at the vaja’s cry, but at the low chuckle from the najd that followed it.

It took two days for the storm to blow itself out. There came a morning finally when the sun emerged in a flawlessly blue sky and the warmth of the day rose with it. The storm’s snow melted and ran off in rivulets down the pathways of the talvsit, carrying the remainder of the old snow with it. Icicles on the thatching of the huts dripped away. Earth and moss and the rotting leaves of last autumn were bared by the retreating snow. As the day grew older, and the herdfolk sought out their reindeer in the shelter of the trees, the retreating snow bared the small still forms of hapless calves born during the late storm. Vajor with swollen udders nudged at little bodies, nuzzled and licked questioningly at the small ears and cold muzzles.

Silent folk moved in the forest, leading vajor away to be milked, leaving the dead calves to the relentless beetles that already crept over them. During the storm, the tale of the najd’s words had crept from hut to hut until all the talvsit knew. Carp sat outside Heckram’s door, stretching his limbs to the warmth of the sun as he fondled something small and brown in his knuckly hands. Those who passed looked aside in fear and wonder, and some felt a hidden anger. Heckram was one of them. What demon had guided this old man to him, and what foolishness had ever prompted him to bring Carp back to the talvsit?

“I lost two calves,” he said coldly, standing over the old man. “And my best vaja, who sometimes bore twins, cannot be found at all. I think wolves got her as she gave birth.”

“A terrible piece of luck,” Carp observed demurely.

“One of Ristin’s vajor died giving birth.”

Carp nodded. “A terrible storm.” He tilted his filmed eyes up to Heckram. “I will be leaving in a few moments. I wish to spend the day with my apprentice.”

Heckram was silent, conflicting urges stirring in him. “I can’t take you today,” he said at last. “The bodies of the calves must be collected, skinned, and the meat burned. It is already spoiled. Otherwise the stench of it will draw wolves and foxes and ravens to prey on the new-born ones as well.”

Carp looked at him coldly. “I do not need you to take me. That is not what I said. As for you, you have no reason to see Tillu. Your face is healed. You have tasks to do. To visit the healer would be a waste of your time.” His tone forbade Heckram.

“The healer and her son are my friends,” Heckram countered. “And sometimes a man goes visiting for no more reason than that.”

“Not when he has work. You have calves to skin and bury. Don’t waste your time visiting Tillu.”

Capiam approached as they were speaking. Acor and Ristor hung at his heels like well-trained dogs. Heckram glanced at them in annoyance, wondering where Joboam was. Carp showed them his remaining teeth in a grin, and went on speaking to Heckram.

“Hides from just-born calves make a soft leather. Very fine and soft, wonderful for shirts. It has been a long time since I had a shirt of fine soft leather. But such luxuries are not for a wandering najd.” He moved his head in a slow sweep over the gathered men. Then, with elaborate casualness, he opened his hand. One finger stroked the carved figure of a reindeer calf curled in sleep. Or death. Acor retreated a step.

“You might have a shirt of calf leather, and leggings as well,” Capiam said in a falsely bright voice. “My folk have urged me to invite you to join us on our migration. We will provide for your needs.”

“I myself will give you three calf hides this very day!” Acor proclaimed nervously.

Carp closed his hand over the figurine. “A kind man. A kind man,” he observed, to no one in particular. “An old man should be grateful. But it would be a waste of hides. My teeth are worn, my eyes are dim, my hands ache when the winds blow chill. An old man like me cannot work hides into shirts.”

“There are folk willing to turn the hides into shirts for you. And your other needs will be seen to as well.”

“Kind. Kind, generous men. Well, we shall see. I must go to visit my apprentice today. Kerlew, the healer’s son. I am sure you know of him. He has told me he might not be happy among your folk. Some might be unkind to him. I would not stay among folk who mistreat my apprentice.”

A puzzled Capiam conferred with Acor and Ristor, but both looked as mystified as he did. He turned back to Carp. “If anyone offers harm to your apprentice, you have only to tell me about it. I will see that the ill-doer pays a penalty.”

“Um.” Carp sat nodding to himself for a long moment. Then, “We will see,” he said, and got creakily to his feet. “And you, Heckram. Do not waste your time today. Get your work done, and be ready to travel. The journey begins the day after tomorrow.”

The men looked to Capiam in confusion. “We do not go that soon,” Capiam corrected him gently. “In four or five days, perhaps, when…”

“No? Well, no doubt you know more of such things than I. I had thought that a wise man would leave by the day after tomorrow. But I suppose I am wrong again. What an old man sees in his dreams has little to do with day-to-day life. I must be going, now.”

Carp set off at a shambling walk, leaving Capiam and his men muttering in a knot. Heckram called after him, “Be sure to tell Tillu that I will come to see her soon.” The old man gave no sign of hearing. With deep annoyance, Heckram knew that his message would not be delivered.

“Here he comes! I told you he would come as soon as the storm died!” Without waiting for an answer, Kerlew raced out to meet Carp.

“I told you that he would come as soon as the storm was over.” Tillu offered the truth to the empty air. Kerlew had been frantic when Carp had not returned. He had spent a miserable two days. Kerlew had paced and worried, nagged her for her opinion as to why Carp hadn’t returned, and ignored it when she told him. So now the old shaman was here, and her son would stop pestering her. Instead of relief, her tension tightened. She stood in the door, watched her son run away from her.

She watched the old man greet the boy, their affection obvious. In an instant, they were in deep conversation, the boy’s long hands fluttered wildly in description. They turned and walked into the woods. Tillu sighed.

Then she glimpsed another figure moving down the path through the trees. Despite her resolve, her belly tightened in anticipation. The long chill days of the storm had given her time to cool her ardor and reflect upon what had nearly happened the last time she had seen Heckram. It would have been a grave mistake. She was glad it had not happened, glad she had not made herself so vulnerable to Heckram. The trees alternately hid and revealed the figure coming down the path. He was wearing a new coat. She dreaded his coming, she told herself. That was what sent her heart hammering into her throat. She would not become involved with a man whose woman had been beaten, and then slipped into death by too large a dosage of pain tea. She would not become close to a man that large, so large he made her feel like a helpless child. She would be calm when he arrived. She would treat his face, if that was what he came for. And if it was not, she would…do something. Something to make it clear she would not have him.

He paused at the edge of the clearing, shifting nervously from foot to foot. It wasn’t him. Recognition of the fact sank her stomach and left her trembling. He hadn’t come. Why hadn’t he come? Had he had second thoughts about a woman who had birthed a strange child like Kerlew? Kerlew, with his deep-set pale eyes and prognathous jaw, Kerlew, who dreamed with his eyes wide open. But Heckram had seemed to like her son, had responded to him as no other adult male ever had. So if it was not Kerlew that had kept Heckram from coming to see her, it was something else. Something that was wrong with her.

Whoever it was who had come hesitated at the edge of the clearing. Tillu watched as her visitor rocked back and forth in an agony of indecision. Then suddenly the figure lifted its arms wide, and rushed toward her hut in a swooping run. The girl’s black hair lifted as she ran, catching blue glints of light like a raven’s spread wings. The wind of her passage pressed her garments against her thin body.

A few feet from the hut, she skittered to a halt. She dropped her arms abruptly and folded her thin hands in front of her high breasts. Her fluttering garments of loose white furs settled around her. She stood perfectly still and silent, regarding Tillu with brightly curious eyes. She did not make any greeting sign, not even a nod. She waited.

“Hello there,” Tillu said at last. She found herself speaking as to a very shy child. The same calm voice and lack of aggressive movements. It seemed to Tillu that if she put out a hand, the girl would take flight. “Have you come to see me? Tillu the Healer?”

The girl bobbed a quick agreement and came two short steps closer. She looked at Tillu as if she had never seen a human before, with a flat, wide curiosity, taking in not the details of Tillu’s face and garments, but the general shape of the woman. It was the way Kerlew looked at strangers, and Tillu felt a sudden uneasiness. “What’s your name?” she asked carefully. “What do you need from me?”

The girl froze. Tillu expected her next motion to carry her away. But instead she said in a whisper-light voice, “Kari. My name is Kari.” She bobbed a step closer and craned her neck to peer into the tent. “You’re alone.” She swiveled her head about quickly to see if there were anyone about. Tillu didn’t move. The girl leaned closer, reached out a thin hand but didn’t quite touch her. “I want you to mark me.”

“What?”

“Listen!” The girl seemed impatient. “I want you to mark me. My face and breasts, I think that should be enough. Maybe my hands. If it isn’t, I’ll come back and have you take out an eye. But this first time, I think if you cut off part of one nostril, and perhaps notched my ears. Yes. Notch my ears, with my own reindeer mark. To show that I belong to myself.”

Tillu felt strangely calm. She was talking to a mad woman. The last snow was melting, leaf buds were swelling on twigs, and the trunks of birches and willows were flushed pink with sap. And this girl wanted Tillu to cut off pieces of her face.

“And there is a mark I want you to make on each of my breasts. We will have to cut it deep enough to scar. Look Here it is. Can you tell what I meant it to be?”

From within her fluttering garments, the girl produced a small scrap of bleached hide. She unrolled it carefully, glanced warily about, and then thrust it into Tillu’s face. She was breathing quickly, panting in her excitement.

Tillu looked at the scrap of hide, making no movement to take it. A black mark had been made with soot in the center of the hide. Four lines meeting at a junction. “It looks like the tracks shore birds leave in the mud,” Tillu observed carefully.

“Yes!” Kari’s voice hissed with satisfaction. “Almost. Only it’s the mark of an Owl. A great white owl with golden eyes. I want you to put one on each of my breasts, above the nipples. Mark me as the Owl’s. Then Pirtsi will know I am not for him. My ears will show me as mine, my breasts will show me as Owl’s. Must it hurt very much?”

The pang of fear in the last question wrung Tillu’s heart. It was a child’s voice, not questioning that it must be done, but only how much it would hurt.

“Yes.” Tillu spoke simply and truthfully. “Such a thing would hurt a great deal. Your ears, not so much after it was done. But your nose would hurt a great deal, every time you moved your face to speak or smile or frown. The nose is very sensitive. As would your breasts be. There would be a great deal of blood and pain.”

She peered deeply into the girl’s eyes as she spoke, hoping to see some wavering in her determination. There was none. Tillu felt a tightening within her belly. This girl would do this maiming, with her help or without it. She must find a way to deter her. Slowly she gestured toward her tent. “Would you care to come inside? I made a tea this morning, of sorrel and raspberry roots, with a little alder bark. As a tonic for the spring, but also because it tastes good. Will you try some?”

Kari opened and closed her arms several times rapidly, making her white garments flap around her. Tillu thought she had lost her, that the girl would flee back into the woods. But suddenly she swooped into the tent. She fluttered about, looking at everything, and then alighted on a roll of hides near the hearth. She cocked her head to peer into the earthenware pot of tea steeping on the coals. “I’d like some,” she said decisively.

Tillu moved slowly past her, to reach for carved wooden cups. “What made you decide to mark your body?” she asked casually.

Kari didn’t speak. Tillu sat on the other side of the hearth, facing her. She dipped up two cups of the tea, and offered one dripping mug to Kari. She took it, looked into it, sniffed it, sipped it, and then looked up at Tillu and spoke. “The night the najd came to my father’s tent and spoke, I felt the truth of his words. And more. He spoke of how many of us had no spirit guardian to protect us. I had heard my grandmother speak of such guardians, a long time ago, before she died. Her spirit beast was Hare. He does not seem like much of a guardian, does he? But he was good to my grandmother.

“So that night, I stared into the fire as the najd had and opened myself and went looking for a spirit beast. But I saw nothing in the flames, though I watched until long after all the others slept. So, I gave up and went to my skins and slept. And in the night I felt cold, heavy claws sink into my beast.”

She lifted her thin hands, her narrow fingers curved like talons, and pressed them against her breasts. Then she looked up at Tillu. The girl’s eyes were a wide blackness. She smiled at Tillu, a strange and wondering smile. Tillu held her breath. “The weight of his claws pressed me down, crushing my chest until I could not breathe. The sharp cold claws sank into me. I struggled but could not escape. It grew dark. But when I was too tired to fight anymore, the darkness gave way to a soft gray light. I felt moss beneath my back, and the night wind of the forest blew across my naked body. And atop my chest, near tall as a man, was Owl, perched with his claws sunk into my breasts!”

Her nostrils flared as she breathed, and Tillu could see the whites all around her eyes. The hands that held the wooden mug trembled as she raised it to her lips. Tillu was silent, waiting. Kari drank. When she took the mug from her mouth, her eyes were calm. She smiled at Tillu, a tight-lipped smile without the showing of teeth. “Then I knew,” she said softly.

Tillu leaned forward. “Knew what?”

“That I belonged to Owl. That I didn’t have to let Pirtsi join with me by the Cataclysm this summer. I am Owl’s. When I awoke, I told my dream to my mother, and asked her to explain to my father why I cannot be joined to Pirtsi. It was always his idea, never mine. I never wanted to be joined to any man at all, let alone a man with dog’s eyes. But my mother grew angry, and said that a man was what I needed to be settled, for nothing else had worked. So I have come to you. Mark my face and body, so all will know to whom I belong. Pirtsi will not take me if I am scarred. He would not take me at all, except that he thinks Capiam’s daughter is a way to Capiam’s favor.”

Tillu sipped at her tea, watching Kari over her mug. The girl was determined. In her mind, it was already done. She spoke carefully. “Kari, I am a healer, not one who damages bodies.”

“Damage? No, this would not be damage. Only a marking, like a notch in a calf’s ear, or a woman’s mark carved into her pulkor. Not damage.”

Tillu chewed at her lower lip. “I do not think we should do this thing,” she said softly, and as anger flared on Kari’s face she added, “If Owl had wanted you so marked on your flesh, he would have marked you himself. Is this not so?”

For an instant, Kari looked uncertain. Tillu pressed on, glad for once that Kerlew had nattered on so much about Carp’s teaching. She wanted her words to sound convincing.

“Owl has marked your spirit as his. That is all he requires. You need not mark your face to deny Pirtsi. Or so I understood during the time I spent with the herdfolk, when Elsa…”

“Elsa died.” Kari finished in an awed whisper.

“I understood then that the women of your folk can choose their mates. You have a reindeer of your own, do you not? Are not the things you make yours to keep or trade as you wish?” At each of the girl’s nods, Tillu’s spirits lifted. “Then say that Pirtsi isn’t what you want. Cannot you do that?”

Kari had begun to writhe. Her fingers clawed at her arms as she hugged herself. “I should be able to do that. But no one listens. I say I won’t have him. They pay no attention. Everyone is so certain that we will be joined at the Cataclysm. It is as if I cried out that the sun would shine at night. They would think it some childish game. They cannot understand that I do not want him; that I cannot let him touch me.”

“Why?” Tillu spoke very, very softly.

Kari’s eyes grew larger and larger in her face. She touched the tip of her tongue to the center of her upper lip. She trembled on the edge of speaking. Then, the tension left her abruptly, her shoulders slumped, and she said, “Because I belong to Owl now, and he tells me not to. Why won’t you mark me?”

“Because I do not believe Owl wants me to,” Tillu excused herself smoothly. “Who am I to make Owl’s mark for him? If he wishes you marked, he will do it himself.”

Kari once more lifted her hands, sank taloned fingers against her breasts. “And if I do it myself?” she asked.

“Then I would try to see that you did not become infected. A healer is what I am, Kari. I cannot change that. Let me offer you another idea. Wait. There is much time between spring and high summer. Tell everyone that you will not have Pirtsi. Say it again and again. They will come to believe you. Tell Pirtsi himself. Tell him you will not be a good wife to him.”

“And if they do not believe me, when the day comes, I will show them that I am Owl’s. By the Cataclysm.”

Tillu sighed. “If you must.”

The girl sipped at her tea, suddenly calmed. “I will wait.” Her eyes roved about the tent interior. “You should be spreading your hides and bedding in the sun to air, before you pack it for the trip. Where are your pack saddles?”

Tillu shrugged. “I have never traveled with an animal to carry my things. I have always dragged my possessions behind me. This migration will be a new experience for Kerlew and me.” Tillu spoke the words carefully, tried to sound sure that her son would travel with her. The old shaman had said he would take Kerlew from her. Kerlew himself had said that he was near a man now, and had chosen to go with Carp. But perhaps he would change his mind. Perhaps he would stay with his mother and be her son a while yet, would not slip into the strange ways of the peculiar old man and his nasty magics. With an effort she dragged her attention back to what Kari was saying.

“You know nothing of reindeer then? You do not know how to harness and load them?”

Tillu shrugged her shoulders, looked closely at the girl who now spoke so maturely and asked such practical questions. “There are two animals hobbled behind my tent. The herdlord provided them for me. I suppose he will send Joboam to help me when the time comes.” Tillu could not keep the dismay from her voice.

“That one?” Kari gave a hard laugh. “I was glad when he wouldn’t have me. I knew why. He made many fines excuses to my father, saying I was so young, so small yet. As if that…” She paused and stared into her mug for a breath or two. “I didn’t know my father would find Pirtsi instead,” she finished suddenly. She cocked her head, gave Tillu a shrewd look. “I could show you. Now, today. Then, when the time came, you wouldn’t need help. You could send a message that you didn’t need Joboam.” Kari smiled a small smile. “And I could tell my father that I had already taught you, that he need not spare so important a man as Joboam for such a simple task.” There was frank pleasure in the girl’s voice as she spoke of spiting Joboam’s plans.

Tillu lifted her eyes from her own slow appraisal of the flames. She was beginning to have suspicions of Joboam that made her dislike him even more. She was also beginning to have a different opinion of Kari. The girl was shrewd. As oddly as she might behave, she had wits. And how old was she? Sixteen? “When I was her age, I had Kerlew in my arms,” Tillu thought to herself. “And I thought my life belonged to him as surely as Kari believes hers belongs to Owl. We are not so different.” Kari smiled her tight-lipped smile again, a smile of conspiracy that Tillu returned.