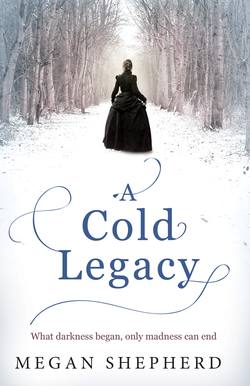

Читать книгу A Cold Legacy - Megan Shepherd, Megan Shepherd - Страница 9

4

ОглавлениеValentina led the way down the damp cellar stairs with a candle in one hand, despite the line of electric lights running alongside us.

“Best not to rely on the electricity,” she explained over her shoulder. “The lights have gone out on me too many times when I’m down here alone, and it’s blacker than the devil.”

The farther we descended, the colder the air grew. My breath fogged in the dim lights. No wonder they stored the bodies here—the temperature and sulfuric gases released from the bogs would preserve them in near perfect condition until the spring thaw, and the stone walls would keep away the vermin.

Montgomery was close behind me, but Lucy trailed at a distance, holding her hem high so as not to drag it on the slick stones of the spiral staircase. At last we reached the bottom, where the distant sound of a droning voice came from a room ahead that glowed faintly in the electric lights.

“It was the plague,” Valentina said.

“Plague?” Lucy asked.

“The ones that died. The plague killed them. Beggars following the winter fair circuit. Several women and children among them, too.”

She spoke casually enough, as though dead children were as common as the sheep dotting the landscape. Lucy gasped, but Valentina’s straightforward attitude didn’t bother me. Back in London, it was all high tea and polished silver. Very refined, very polite. At least these people, sullen though they were, didn’t deny the dangers around them.

Lucy lifted her skirts higher, as if the plague might be lurking in the damp stone underfoot, and Valentina smirked. We followed her through an open doorway into a chamber where a dozen or so servants, most of them young girls, gathered around a brass cross set on an altar.

“A chapel?” Lucy whispered to me. “In the cellar?”

I nodded. I’d heard about places like this. In such cold climates, when going outside was nearly impossible half the year, old households had built chapels indoors. Parts of this one, crumbled as it was, looked as though it dated back practically to the Middle Ages.

A few of the girls looked up when we slipped in, curiosity making them fidget. None were dressed as puritanically as Valentina, though all their clothes were rather dour and old-fashioned. It was a stark contrast to their bright eyes and red cheeks. Clearly they hadn’t known or cared about any of the deceased, because I caught a few excited whispers exchanged about Lucy’s and my elegant dresses, and Montgomery’s handsome looks.

Valentina shushed them and they snapped back to attention.

At the head of the room stood an older woman with a red braid shot through with white hairs, who wore a pair of men’s tweed trousers tucked into thick rubber boots. She was reading a few somber verses from a leather-bound volume in a heavy Scottish accent. She hadn’t yet noticed our presence.

On closer inspection, I realized all the servants were women, most of them barely more than children. Where was the rest of the male staff, besides the old gamekeeper?

Montgomery stood just in the doorway, as though it would be trespassing to go any farther. When I met his eyes, he was frowning.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

He leaned down to whisper in my ear. “The bodies. I didn’t expect so many of them.”

The servant girls shifted, and I caught sight of the bodies he was talking about. A dozen of them were laid out on stone benches and the floor, covered with white sheets. My stomach knotted, reminding me of the King’s College autopsy room, where Edward’s victims had been laid out the same way. Dr. Hastings and the others I’d killed would have been laid there as well, after the massacre. Their wives and children would have come to identify the corpses. I suddenly felt sick.

Lucy drew in a breath and crossed herself.

“Don’t worry,” Montgomery whispered to her. “The germs will be long gone by now. There’s no danger of us catching it.”

Valentina walked among the servant girls, stepping unceremoniously over one of the bodies, and whispered to the older woman, whose eyes shot to us as she said a few final words. As soon as the brief service had concluded, the red-haired woman motioned for us to follow her into the hallway.

“Goodness me,” she said, pressing a hand to her chest. “Strangers during such a storm? And to arrive during these poor souls’ funeral—you must never have suffered such shock. Look at you, frozen through and through. You must be starved.”

The woman had a motherly way about her that made me feel safe even standing among the dead, and an enormous weight shifted off my shoulders. At least someone was giving us a warm reception.

“Are you Mrs. McKenna?” I asked.

“I am, my dear. My family has helped the von Steins with the management of this household for generations; you’re in good hands, I promise, and if the mistress has sent you, then you’re more than welcome here.” She turned back toward the chapel. “Lily, Moira, you girls go make up the rooms on the second floor for our guests.”

Two of the older girls skipped off into the hallway, more than glad to escape the dreary funeral. Mrs. McKenna first took my hands, then Lucy’s, and even Montgomery’s big ones, rubbing them and tsking at the cold as if we were children. “Come with me, little mice. We shall get you warmed.”

I cast one final look back at the bodies. Mrs. McKenna pressed a hand against my shoulder, turning me away from the sight. “Aye, a shame. They took shelter here a fortnight ago—I could hardly turn them away, not with so many children among them. And the mistress would have wanted it. But they brought with them the plague, and it took all of them overnight. I doubt they have any relations who will be coming by to collect the bodies.”

“None of your staff caught the plague?” I asked, as we made our way back up the spiral stairs with Valentina wordlessly trailing behind us.

“No, thank heavens. The vagrants slept in the lambing barn while they were here. I had Carlyle burn it as a precaution, though in these parts, at this time of year, it’s too cold for diseases to spread easily in a house like this. We keep it well cleaned.”

Her knowledge of biology impressed me, but no more so than Valentina’s ability to read. It was rare for servants to be highly educated, especially in such rural parts.

We entered the kitchen, a cavernous room with a roaring fire and a pair of geese roasting on the spit. My stomach lurched with hunger. A thin girl attended to the roast, chewing her nail as she regarded us with round eyes. Mrs. McKenna opened a tin and handed Lucy, Montgomery, and me each a crusty scone.

“That’ll tide you over till supper. Let’s get you settled now, and tomorrow I’ll show you the manor and grounds, if the storm lets up. There are times it gets so bad the levees fail and the road to Quick floods for days. We can be completely cut off. Our own little island, of sorts.” She handed me the candelabrum from the table. “Take this. The electricity will likely go out if the wind continues. Follow Valentina—she’ll show you to your rooms. I’ll make sure my girls take care of your sickly friend. A fever, is that right?” She shook her head in sympathy. “How awful. We shall put him in a room with a fireplace to keep him warm.”

“That would be lovely—” Lucy began.

“No,” Montgomery interrupted. “No fire. No sharp objects either. And make sure the room has a strong lock. We’ll attend to him ourselves, not your girls.”

Mrs. McKenna’s eyebrows raised, and she exchanged a look with Valentina, but like any good servant, she didn’t probe. “No fire, then. And an extra lock on the door.” She paused. “Might I see that letter of introduction?”

I handed it to her, and she read Elizabeth’s letter, then looked up with a startled expression. Her gaze shifted between Montgomery and me.

“Engaged?” she asked.

Behind her, the thin little girl at the goose spit gasped.

“Yes,” I said, worried. “Is … is it a problem?” With their high-collared dresses and sleeves down to their wrists, they might be religious types who wouldn’t approve of Montgomery and me traveling together unwed.

“No, no, little mouse,” Mrs. McKenna said. She glanced at the thin girl at the spit, who now wore a bright smile that seemed out of place in the gloomy manor. “It’s only that, with the exception of old Carlyle, you’ve walked into a house of women. We haven’t had much occasion to celebrate things like engagements, not in a long time. The girls would so adore helping to arrange a wedding. Perhaps in the spring, after thaw, or midsummer when the flowers are in bloom. It’ll cheer them up so, especially after a harsh winter.”

I smiled. “We’d love their help. And spring sounds perfect.” The warm scone in my stomach, Montgomery at my side, girls tittering over wedding plans: it was starting to feel more like a home, and I told myself that the unsettled feeling I’d had when I first arrived was just nerves from the road.

I squeezed Montgomery’s hand, but the troubled look he gave me said he wasn’t nearly as reassured as I was.

“THERE ARE THREE FLOORS, not including the basement,” Valentina said as she led us up the stairs, with Balthazar trailing behind carrying our three carpetbags over one shoulder. Two of the littlest servant girls walked alongside him with fresh linens in their arms, staring up at him. One had a limp that made her walk nearly as slowly as he did. Far from frightened, they seemed utterly transfixed by him.

“That doesn’t include the towers,” Valentina continued. “There’s one in the southern wing and one in the north. The north tower is the biggest. It’s where the mistress’s observatory is. I’m the only one with a key to it, on account of the delicate equipment. She’s taught me how to use most of the telescopes and refractors and star charts. In turn, I’m teaching the older girls. Education is often overlooked in female children; I’m determined to make sure the girls here have good heads on their shoulders.” She cast me a cold gaze. “Between McKenna and me, we manage quite well during Elizabeth’s absences. Though we’re all eager for her return, of course.”

The stairs creaked as we made our way to the second floor, which Valentina explained was mostly comprised of guest bedrooms and a library they used for breakfast. The regular servants’ rooms were on the third floor, and she and McKenna each had one of the larger corner rooms in the attic. Carlyle slept in an apartment above the barn.

She passed me a set of keys with her gloved hand. “One for your bedroom, and one for that of your ill friend. You’re welcome in any portion of the house that isn’t locked. Those are the observatory and the mistress’s private chambers.”

“And my dog?”

“Carlyle put him in the barn. There are plenty of rats for him to catch.”

Lucy gaped. “He’s supposed to eat rats?”

Valentina appraised Lucy’s fine city clothes with a withering look. “I didn’t realize he was canine royalty. Would he care for a feather bed and silver bowl, perhaps?”

Lucy drew in a sharp breath. I could practically see smoke coming from her ears. I doubt she’d ever been spoken to so boldly, by a maid or anyone else. I wrapped my arm around hers and held her back. “Rats will be fine,” I said.

Valentina smiled thinly and continued up the stairs.

We reached the landing, where a long hallway stretched into darkness broken only by flickering electric lights. Heavy curtains flanked the windows, with old portraits hanging between them.

“The Ballentyne family,” Valentina said, motioning to the portraits. “That one is the mistress’s great-grandfather. And that woman is her great-aunt.”

“But I thought the Franken—I mean, the von Stein family—owned the manor,” I said.

“Victor Frankenstein, you mean? You needn’t be so secretive, Miss Moreau. Elizabeth trusts us completely; she’s told us all about her family’s history. The Ballentynes were the original owners of the manor. The first Lord Ballentyne built it in 1663 overtop the ruins of previous structures. He was something of an eccentric. Went mad, they say.”

Montgomery stopped to give Balthazar time to catch up to us. The two little girls were hanging by his side, hiding smiles behind their hands. The one with the limp skipped ahead to Valentina and tugged on her skirt. Valentina bent down to hear the girl’s whisper.

“The girls say your quiet associate—Mr. Balthazar, is it?—belongs here.” She pointed a gloved finger at a small portrait beneath a flickering electric lamp. “They say he’s the spirit of Igor Zagoskin.” The portrait portrayed a large man in an old-fashioned suit, stooped with a hunchback, face covered by a hairy beard. Balthazar blinked at the painting in surprise. The resemblance was striking.

“Who is that man?” Montgomery asked.

“One of Lord Ballentyne’s most trusted servants, back in the 1660s. He was rumored to be a smart man, strong as an ox. He helped Ballentyne in his astronomical research.”

Balthazar blinked a few more times in surprise, then grinned at the girl with the limp. “Thank you, little miss. I like the look of him. I shall hope to carry on in his tradition.”

“Your room is through here, Miss Moreau.” Valentina opened a door into a bedroom that emitted the smell of mustiness and decades of disuse, but inside I found it freshly tidied. Balthazar set my bag on the soft carpet. Valentina handed me a smaller key.

“What’s this one for?” I asked. The bedroom door had only one lock.

“A welcome present from McKenna.” She smirked. “I’m sure you’ll figure it out soon enough. Mad Lord Ballentyne was full of surprises when he built this house.”

The little girl with the limp giggled, and Valentina shushed her and swept her out of the room, leaving me alone while she showed the others to their rooms down the hall.

I went to the window, where I could make out little in the dark rain. Lightning crackled, revealing a sudden flash of ghostly white. I jumped back in surprise. It looked like enormous white sheets, spinning impossibly fast, and I threw a hand over my heart before the whirling shapes made sense.

A windmill.

At least now I knew the source of Elizabeth’s electricity. Glowing lights flickered from the other exterior windows on this wing. I wondered which room was Montgomery’s, and Lucy’s, and which room they’d put Edward in earlier. Sorrow washed through me at the thought of him. If only Lucy’s premonitions were right, and the fever would break and he’d be himself again, miraculously cured of the Beast.

Unfortunately, I wasn’t nearly as optimistic as Lucy. Sometimes things didn’t work out for the best. The King’s Club massacre, for one. It had been a messy, cruel solution, even if it had saved us.

Would I take it back, if I could?

The answer eluded me, and I started to pull the drapes closed over the window, tired of the same guilty thoughts circling in my head, only to find that the curtains spanned a wider section of the wall that hid a secret door. The small key Valentina had given me was a perfect fit, and I swung it open.

I let out a soft sound of surprise when I found a second bedroom that was like a mirror to my own—except for the young man standing by the wardrobe in the process of undressing. Montgomery turned at the sound of the door. His suspenders hung by his side, his blond hair loose and still damp from the rain.

“Adjoining bedrooms,” I explained, holding up the key. “This must be the welcome present Mrs. McKenna meant for us. How scandalous. I guess the household isn’t as puritanical as their clothes make them seem.” I tried to keep my voice light. Since fleeing London we’d barely spoken, and I didn’t want our new life here to begin in sullenness. But he came to the doorway and rubbed his chin, distracted.

“What is it?” I asked.

“It doesn’t feel right,” he said. “Those bodies in the cellar. This place, these people, greeting us with a rifle to our heads.” There was fear in his expression, which made my heart dim. Montgomery was rarely afraid of anything.

“It’s better than being arrested for murder,” I said.

He raised an eyebrow, unconvinced. “Well, of course. The housekeeper is kind enough, and they’re good to take us in, but they’re hiding something. I can smell it.”

“Does it smell like musty old clothes?” I tried to lighten the mood again. “Because that’s just the carpets.”

He tensed, not in the mood for joking.

“This isn’t London,” I said, more seriously this time. “Elizabeth clearly lets them run wild, and they’ve no idea what to do with us. You saw the disdainful look Valentina gave Lucy, like we’d die without our tea and crumpets.” I laid a hand on his chest, toying with his top button. “I suspect she’s just jealous of our nice clothes and fancy address in the city.”

For a moment we stood mirrored on either side of the door while the wind whistled outside. His jaw tensed, and he stepped back so my hand fell. “We don’t have a fancy address anymore. We can never return to London, not since you murdered three men.”

I blinked. The fire crackled, heat trying to push us even farther apart, and my heartbeat sped up. “You know I had no choice. I didn’t want to do it.”

“That isn’t what you said at the time. I could see in your eyes how badly you wanted to kill Inspector Newcastle. You burned him alive.” He paused, breathing heavily, arms braced on either side of the door. I could only gape, wanting to deny the accusation but not quite able to. “Sometimes you remind me so much of your father, it’s frightening.”

The sting in his words settled into the curtains and bedspread like the smell of chimney smoke, and just as impossible to get rid of. “It was better than letting them use Father’s research,” I said in my defense. “They would have hurt so many more people. Father would have helped them, not stopped them.”

He cursed under his breath. “I shouldn’t have said anything.”

I placed my hand on my forehead, trying to calm the blood searing in my veins. “No. Don’t apologize. We said we’d always be honest with each other. And if I’m being honest with you, I think you should be thankful we have a roof over our heads and walls around us, and stop questioning Elizabeth’s generosity. There’s nothing wrong with these people, and there’s nothing wrong with me.”

I closed the door in his face, twisted the key, and leaned my back against it. He knocked and called to me, but I didn’t answer. I crawled into bed and thought about Montgomery’s words. It was true that I’d been obsessed with bringing the water-tank creatures to life, even knowing the bloodshed that would follow. Maybe the fortune-teller was right. Reading the future was nonsense, but there was a grain of truth in how his predictions had made me feel—as though escaping Father was impossible, even in death. Maybe, just maybe, I should stop trying so hard to fight it.