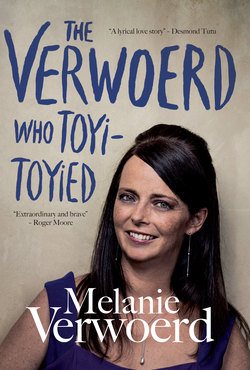

Читать книгу The Verwoerd who Toyi-Toyied - Melanie Verwoerd - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

Since my earliest memories, my head and my heart seem to have been in a tension-filled dialogue. My intellect, filled with the writings of Shakespeare, the history of colonial powers, and art, music and religion from worlds far away, is most comfortable in the thinking patterns of Europe. Of course, my white skin, and the language I speak, make that even more evident. But something deep inside me has always rebelled against this European identity. Since I was very young, I have known that there is something else, something much deeper. Something that was formed by the red soil of Africa, the thunderstorms, the air, the harshness of the landscape, and the vast diversity of the continent’s people. With time, I have come to understand and accept that I stand with my feet in two worlds: in the Europe of my head and in the Africa of my heart.

Physically, I came into this world at 5:40pm on 18 April 1967 in Die Moedersbond Hospital in Pretoria. It was a turbulent time in South Africa. Almost exactly three years after Mandela’s famous speech from the dock, and his subsequent sentencing to life imprisonment on Robben Island, the National Party government was determined to keep the political insurgency under control by banning, among others, the ANC and PAC.

Seven months earlier, the prime minister, Hendrik Verwoerd, with whom I would become inextricably linked twenty years later, had been assassinated in parliament. After the Sharpeville massacre in 1960, the military wing of the ANC had increased its activities. In response, the apartheid government passed both the Defence Amendment Bill and the Terrorism Bill in June 1967. This made military service compulsory for white men, and also legalised the detention without trial of anyone who ‘might endanger the maintenance of law and order’. Cut off by the rigorous division between people set up by apartheid, the white population was not really affected by the latter, and celebrated proudly when Dr Christiaan Barnard performed the first heart transplant later that year in Cape Town.

Like Dr Barnard, I know that my ancestors came from Holland centuries ago. However, as with many Afrikaners, the details are a bit hazy. Through an extraordinary piece of research done by Professor Geoffrey Dean from Ireland, I know that I am, on my father’s side, a descendant of Gerrit Jansz and Ariaantje Jacobs. Gerrit Jansz came to the Cape in 1685 as one of the first free burghers sent by the Dutch East India Company to set up a half-way station at the southern point of Africa for the ships going to the Far East. Gerrit was given a piece of land, but had no wife. In 1688, the Lords Seventeen in the Netherlands, who directed the business of the Dutch East India Company, sent out eight female orphans on a ship called China as wives for the free burghers. One of them was Ariaantje Jacobs – or Ariaantje Adriaanse, as she was also known – an orphan from Rotterdam. The plan of the Lords Seventeen seemed to work, since the majority of the women were married within a month. Ariaantje married Gerrit Jansz and together they had eight children. But this is where my knowledge of the story ends.

During 1840, my ancestors must have joined the Great Trek. Bravely – some would argue, stubbornly – they faced enormous obstacles, including disease, war and almost impassable mountain ranges, in the firm belief and hope that their destiny lay somewhere else, free from British domination. This independent, courageous and adventurous spirit seems to be part of the genetic memory of most Afrikaners; it is certainly part of my genes.

But it was my maternal grandmother who ultimately had the biggest influence in my life. Our relationship was simple: I completely adored her and she completely adored me. A small but strong and determined woman, she had an extremely sharp mind and a great sense of humour. I loved nothing more than spending time with her on my grandparents’ farm. During the day, I followed her when she collected the eggs and watched carefully as she made butter, dried peaches, baked bread and rusks, and cooked the most delicious food known to man on the wood-burning Aga stove. I would sit happily with her in the kitchen as she sang along to the religious music on the radio while ironing or cooking. In the afternoon, we would lie outside under the tree on a blanket, hoping to catch a cool breeze, and imagine that we saw human faces in the big white clouds drifting in the seemingly endless African sky.

But it was at night that I felt completely safe and comforted. As soon as I arrived, my grandfather would be exiled to the guest bedroom and I would snuggle up at night against my granny’s back. In the winter, she would tell me endless stories while we lay in the dark, barely able to breathe under the heavy load of blankets. It was through these stories that she instilled the values and beliefs that would inform everything I would do later in life.

‘You come from a line of very strong women,’ she would repeat over and over again. ‘We lead the men. If it wasn’t for us, they would never have made it across the Drakensberg or survived the Boer Wars. Always remember that!’ She would then go on to tell me how my great-grandparents on my mother’s side had settled on a farm called Leeupoort, back when wild lions still roamed freely. She would tell me stories of my ancestors and of my great-grandmother, Helena Gertruida Maria Dreyer, and her marriage to my great-grandfather, Coenraad Jakobus van der Merwe, and how they settled down on Leeupoort, the farm that belonged to my great-great-grandmother. Unconventionally, the women in my family were always the landowners – their husbands joined them on the land.

It was on Leeupoort, in 1915, shortly after the beginning of World War I, that my grandmother was born, the fifth of seven children. She was named after her mother, and was called Lenie for short. But tragedy struck in 1930 when, at the age of 50, my great-grandmother passed away from pneumonia, leaving my grandmother, who was only fifteen at the time, with the responsibility of looking after the family. Her two elder sisters had already left home, so, as the eldest girl, she was expected to leave school and look after her two elder brothers, her teenage sister and her ten-year-old younger brother.

Ten years later, she met my grandfather, Johannes Petrus (Jan) Brandt, at the wedding of her cousin. Unlike my grandmother’s family, my grandfather came from the Cape. He was born in the French Huguenot town of Tulbagh on 21 August 1912. His mother, Helena Jakoba Johanna Louw, and his father, Jakobus Johannes Christiaan Brandt, lived on a farm where Jakobus was a foreman or overseer. Like his bride-to-be, my grandfather never went to high school. His parents were extremely poor and there was only money for one child to study. My grandfather went to work so that his elder brother, Grammie, could continue his studies. While his brother became a geologist, my grandfather worked as a labourer. Eventually his brother, who was working as a geologist on the gold mines in the Transvaal, suggested that he join him and become a miner. So he left the Cape and travelled the thousand miles to the north to work underground; it was during this time that he met my grandmother.

They had a small wedding and went on honeymoon to the Cape, but since my great-grandfather lived with them, he went too! ‘Well, he wanted to see the sea,’ my grandmother would laugh. After their marriage, my grandmother insisted that my grandfather leave the dangerous mine-work. He took up small-scale farming and drove the local school bus as a source of additional income. He subsequently worked at the brick-making factory in the adjacent town, Carletonville, and in his later years he worked in the mills in the closest town, Fochville.

My grandfather was a big, quiet man. He had enormous hands, hardened by years of working the land. But he had a soft heart. He announced one day that he would no longer shoot the pig he used to feed daily to fatten up until the fatal day. He felt it was a betrayal of his bond with the pig, and told my grandmother that she could do it if she felt that strongly about eating pork. From then on, they bought their pork from the local butcher. No one ever left my grandparents’ house without bags of vegetables, and if anyone knocked on their door, they would be given food. Needless to say, the word spread, and my grandfather made very little money from farming!

As I got older, I would follow my grandfather around while he worked in the vegetable fields or with the animals. He taught me how to milk cows and drive a tractor. He tried to teach me to shoot a gun, but I was hopeless at it. I hate guns with a passion and I have never, nor will ever, own a gun. So every time I had to aim, I would close my eyes and of course hit everything except the tin target. My grandfather gave up in exasperation one day after I nearly hit him.

My grandparents had two children. My mother, Helena (also called Lenie), was born in 1943, and her brother Hannes was born in 1949. Like most Afrikaners at that time, my grandparents were extremely poor. The house was basic, without running water or electricity. I was already at school (in the 1970s) when they finally got running water and no longer had to collect it from the river every day. Even better, they had a water-borne sewage system installed, which meant that the long walk to the pit toilet and night pots under the beds were at last things of the past. It took many more years (until the late 1980s) before they got electricity.

Despite these difficult circumstances, it was extremely important to both my grandparents, and in particular my grandmother, to ensure that both her children got a university education. From early on, she instilled in them the ambition to strive for something more, and to get an education. At night, by candlelight at the kitchen table, they studied for hours.

It paid off. My mother passed her Matric with flying colours and went on to Potchefstroom University to do a Bachelor of Science and an Honours degree in mathematics. She would later become one of the first women in South Africa to get a Masters degree in computer science, at a time when a computer took up most of a room. My mother’s brother received a degree in pharmacology and is a very successful pharmacist. Until her death, my grandmother regarded the fact that she had put both her children through university without incurring any debt as her biggest achievement.

My mother met my dad, Johannes Hendrik Philippus van Niekerk, at university. Bennie, as he was known, was a very attractive pharmacology student and, like my mother, was ambitious and full of dreams for a better future – which was part of the attraction. His father, my grandfather, was a teacher who later became a big commercial farmer on the northern border of South Africa, close to Zeerust. In 1963 my parents got married, and in 1965 they moved to Pretoria. The move was a source of bitterness for my mother, who had been offered a teaching position at her university – an extraordinary achievement given her background and the fact that she was a woman. But my dad insisted on going to Pretoria, where he opened a pharmacy in the suburb of Menlo Park. My mum joined the Atomic Energy Board, where she continued to work as a computer programmer until shortly before my birth in April 1967.

I was born into what was, according to all accounts, a deeply troubled marriage. My dad was an alcoholic and struggled with addictions all his life. My mum was ambitious and determined to make a better life for herself and her children. In December 1969 they separated and a final divorce came through in May 1970. I was only three years old and cannot remember any of the troubles. I have a vague recollection of the big swimming pool and sandpit, as well as our two boxer dogs, Lady and Sir, but nothing more.

Following the divorce, my mum returned to her job as a computer programmer at the Atomic Energy Board. She and I moved from our very big, comfortable house in the suburbs to a one-bedroom apartment in the centre of Pretoria, where we lived until I was almost five years old. I have a few recollections of the time in the apartment. They are happy memories of times with my mum, which would lay the foundation for the very close relationship we still have today. I remember the crèche – in particular the food and naptime, as well as outings to the nearby park to look at the bridal parties, who often had photos taken there. A less happy memory is of my tonsils being removed. I can clearly remember the surgeon’s face and surgical cap, as well as the big operating lights. I also have a vivid recollection of waiting for my dad to visit after the operation. He never came – a pattern of disappointments he would repeat until his death almost 25 years later. During the period following my parents’ divorce, I spent an increasing amount of time with my grandparents in Leeupoort.

Despite what must have been tension-filled times at home, my days on the farm were happy and carefree. I would run around barefoot, loving the feel of the deep-red soil – particularly when it was wet – under my feet and between my toes. Like all farm kids, I quickly learnt to keep an eye out for snakes and scorpions – and the enormous thorns from the African thorn trees. At night I would collapse, exhausted but exhilarated.

A less happy part of life on the farm was the complex relationship my grandparents had with their farm workers. They were, like the majority of white South Africans at the time, racist. It was a racism born out of a sense of superiority on the one hand, and fear on the other. Yet at the same time there was a close and almost loving relationship born out of Christian values shared with their workers.

As it was a small farm, they only had one domestic worker, called Johanna. She and my grandmother would work side by side, talking like friends for hours. Yet at night Johanna would go home to a little shack on the farm. When I saw Johanna’s shack for the first time, I was almost seven years old. I was upset and had an argument with my grandparents, telling them how I would change everything one day when I inherited the farm. They laughed at me, which drove me to angry tears, made worse by my being forbidden to go near Johanna’s house again.

Yet, ironically, it was my grandparents who laid the foundations that would lead me to enter liberation politics later on. Through my relationship with them, I learnt early on that education, wealth and status told you little about a person. My grandparents had almost no formal education. They were extremely poor and were not regarded as movers and shakers in society. But they were dignified, humble, caring and cultured people who were wise beyond any ‘book knowledge’.

Years later, when I was a political activist, I felt completely at home in townships and with farm workers. Not only did the sound of the animals and smoke in the air remind me of Leeupoort, but the caring, simple nature of the people reminded me of the deep bond I shared with my grandparents – even though they were disgusted with my political beliefs.

In 1971, my mum remarried. Philip Fourie was a colleague of hers at the Atomic Energy Board – and the polar opposite of my dad. An intellectual with a doctorate in physics, he was far more introverted and, thank God, stable than my father. I had no objections to the wedding, although I was livid when my mum insisted that I wear a white-and-baby-blue knitted pant suit to the wedding! Even though it was the seventies, I was furious that I could not wear a dress and, according to my grandparents, I tried to boycott the wedding. It is obvious from my grumpy face in the photographs that I was there under duress.

Thankfully, my and Philip’s relationship improved dramatically over the years from the low point of the wedding day, and he became a father to me. A year after the wedding, we moved to a bigger house in the suburbs, which they built just in time for my sister Melissa’s birth in April 1972.

I was five years old when Melissa arrived, and it was a happy change to my life. I was overwhelmed with joy at having a sibling, even though Melissa was an extremely unhappy baby who screamed most of the day. I stayed with my grandparents on the farm while my mum was in hospital. Shortly after the big day, my grandparents and I made the two-hour drive to Pretoria, to the same hospital I had been born in, so we could see the new little arrival. However, it was hospital policy not to allow children in, so I had to wait outside. Already grumpy after getting sick in the car, I was extremely upset when I could only wave at Mum and my new baby sister, who were standing at a window two storeys up. Philip brought me a gift to keep me busy while my grandparents were inside. It was a little ironing board and iron. I was disgusted! I still hate ironing to this day.

At the end of 1972, Philip got a post at the University of Stellenbosch and we made the thousand-mile move to the Western Cape. I found it traumatic to leave my beloved grandparents. My mum also resented the move and in particular hated living in the Strand, where my parents decided to live. During this time I also had to start visiting my dad, as per the divorce agreement, which meant a two-hour flight on my own to Bloemfontein, the closest airport. My dad, or his new wife, Dawn, would pick me up, and we would make another two-hour journey to Welkom, the mining town where they lived.

Alcoholism and addiction would remain a life-long struggle for my dad, which made these holidays treacherous and unpredictable. I never knew whether I would find the loving, doting dad or the aggressive, emotionally unstable dad, or indeed if he would even be there. Thankfully, Dawn was a lovely person who looked after me and tried to buffer the emotional outbursts as much as she could. The annual five-week-long summer holidays were very difficult times for me.

Like any child, I grabbed onto any promise or gesture of a loving relationship, but quickly learned never to trust that it would last. Like most children who grow up in alcoholic families, I learned to control the parts of my environment and life that I could, and having control became more and more important to me. This is of course not necessarily a good thing, since life cannot be controlled – which is something that continues to scare and frustrate me. On the positive side, I learnt to become independent and self-sufficient at a very young age, and through the long holidays, without any friends my own age, I became comfortable with my own company. Through necessity, I learned to go deep inside myself when I was sad or emotionally in trouble. ‘Disappearing’ into myself is something I still do when I am having a really hard time, even though I now know that talking to others (if they can be trusted) can make life easier and help with healing.

What I hated most about these holidays was being separated from my mum and sisters. Yet legally I had no say, and continued to go until I was thirteen. I knew I had a say by that age, and following an especially disastrous holiday, where the alcohol abuse led to very erratic and painful behaviour by my dad, I decided not to see him again. It would be six years before we saw each other again.

In the meantime, I started school in Lochnerhof Primary in the Strand. I remember my first day vividly. Having had enough practice of going to visit my dad, there was never even the slightest option of tears. I was nervous, but in control. I was a bit disappointed in the first day’s schedule and could not understand why we did not have more academic work. But I settled in fast and from the second day I cycled to school on my own, even though I was not quite six years old.

In January 1975, my second sister, Nadine, was born – while I was on my annual holidays with my dad. I was almost eight and was beyond myself with excitement for months. Not being able to be at home during this time upset me bitterly. Philip collected me at the airport a few days after the birth and took me to the hospital, where my mum was recovering after a Caesarean section. At least this time I could go into the room – although the babies were kept in a separate baby room, so again I could only see my little sister behind glass. My sisters and I were always, and remain, very close, even though I am quite a bit older than them.

Shortly after Nadine’s birth, we moved to the nearby town of Somerset West. My mother finally got her escape from the Strand, which she so despised, and built a beautiful house on a hill overlooking False Bay in a new development called Heldervue. At that time there were only about 30 houses in a very big area and there were still guinea fowl, chickens, snakes and the occasional fox.

I started going to De Hoop Primary School, a dual-medium school – which meant that all assemblies and announcements were in both Afrikaans and English. Of course it was all-white, which did not strike me as strange at all. The dual-language policy helped to improve my English at an early age, which was a huge gift.

Something else that improved my English was ballet lessons. I had started ballet two years earlier, in the Strand. For two years, once a week, I would go to the stern and very English Ms Liz Millington. I immediately loved ballet and practised non-stop. When we moved to Somerset West, I was more worried about finding a new ballet school than anything else. Luckily we found a lovely, warm and creative woman, Beverly Luyt, who was an extremely talented teacher, and I would go to her two or three times a week for classes.

Living out in Heldervue was lovely, but being a bit outside the town meant taking a school bus and then walking twenty minutes from the bus stop. This was fine in winter and I never cared about walking in the rain, but in the scorching summer heat it was terrible.

I did well at primary school and was elected prefect in my last year. I was very proud when I won the cup for best bilingual student at the prize-giving. I never did much sport, focusing on ballet instead. I tried out for netball, but gave up after a teacher laughed at me when I missed a ball. After overhearing her comments, I believed for years that I had no ball sense. I played recorder and socialised with friends. I also became involved in church activities. Like most Afrikaners, my parents belonged to the Dutch Reformed Church and we went to church on Sundays. After the service I would join other children in Sunday school, where we would get more lessons. We also had youth groups in the week.

Fortunately, the one thing my mother resisted was ‘Voortrekkers’. An Afrikaner version of the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, it was at that time ideologically driven, race-conscious, nationalist and religious. My mum flatly said no, arguing that she had no intention of ironing silly brown uniforms or driving us around on Friday evenings (which was when meetings took place). It was only later that I realised that she had far bigger political concerns, but protected us by not expressing them.

During these years, the political situation in South Africa started to penetrate my world. We had a lovely coloured lady who helped with cleaning once a week. Sometimes we would drive this very dignified older woman home. Going into the Coloured areas was like a different world, even though, as I would discover years later, conditions in the coloured areas were generally better than in African townships. On the drive back to our house, my mum would become upset and talk about how wrong this was. It made a deep impression on me. We also had an African man, Ernst, who helped in the garden once a week. Ernst and I would chat for hours, and when I discovered that he could not read, I was shocked.

One rainy night, our doorbell rang. It was late and I heard urgent and upset voices at the door. I went to have a look and saw Ernst and a woman, whom I assumed was his wife, standing in the door with a baby in a blanket. They were drenched and looked very distressed. My mum did not see me behind her, but when she pulled the blanket back to look at the baby, it was clear from everyone’s reaction that the baby was dead. I must have gasped in shock, since my mum turned around and rushed me back to bed. I was upset for days about what had happened. My mum explained that the baby had died from a chest infection. Nadine, who had croup a few weeks earlier and had to be hospitalised, was now fine, so I could not understand why Ernst’s baby had died. My mum explained that they had no money for the hospital and that, as they were living in a shack, it was too cold and wet in the winter for small babies. I was struck by the injustice of it all. I kept remembering the little lifeless bundle and could not sleep properly for weeks. Maybe if I can teach Ernst to read, it would make things easier, I thought. I quietly gave Ernst all the money from my piggy bank, but I still felt infuriated by the fact that I could not do anything about the situation.

A similar but much bigger sense of injustice was to result in a turning point in South Africa’s history during this time. On 16 June 1976, thousands of schoolchildren in Soweto marched in protest at the enforcement of a long-forgotten law requiring secondary education to be only in Afrikaans. The protests were peaceful, but when they met a large police presence on the way, some children threw stones. One policeman, a Colonel Kleingeld, drew his pistol and fired a shot, causing panic. The police then opened fire, and hundreds of young people were killed. These killings sent shockwaves through South Africa, and large-scale riots broke out everywhere.

The army was deployed, but the military presence only escalated the anger and violence. Even though I was only nine years old, I was aware that something was going on. I would hear anxious conversations between my parents and their friends. Philip was asked to join the local community watch, and would leave at night to stand guard. I did not know where he went or what he did, but I knew that my mum was always anxious at night, and we became more security-conscious. I felt a deep sense of insecurity and found it difficult to sleep; the slightest sound woke me. Luckily, things calmed down towards the end of 1976, although it took a lot longer for my sleeping patterns to return to normal.

By 1980, my mum was also working at the University of Stellenbosch as a computer programmer. Between the music lessons, ballet lessons and working forty-five minutes away from home, all the driving became too much for my mum. Reluctantly, she agreed to move to Stellenbosch, even though she loved Somerset West and would never really settle in our new home. I was about to begin high school, Melissa was also in school, and Nadine was about to start school.

Stellenbosch is a very different place from Somerset West, even though the two towns are geographically close to each other. It is more class-conscious and snobbish. Stellenbosch was largely Afrikaans. Politically and ideologically, Stellenbosch was strongly nationalist, and with the help of the university, which would provide an intellectual justification for apartheid, it became the bastion of Afrikaner nationalism.

This was evident in the high school I attended. Bloemhof Afrikaans Girls’ High is the oldest Afrikaans girls’ school in the country. Even though it was a state school and therefore had no tuition fees, it was steeped in the traditions associated with exclusive British private schools. The impressive buildings were surrounded by even more impressive gardens, sports fields and, of course, an Olympic-size swimming pool. There was a strong sense of exclusivity, reinforced by the fact that we only rarely engaged with the boys’ school across the road, Paul Roos Gymnasium, and never had any interaction with the adjacent English girls’ school, Rhenish Girls’ High.

The principal of the school was Miss Coetzee, an elderly spinster who ran the place with an iron fist. It was her goal in life to develop Christian ladies who would become upstanding citizens, even if it was just to support their husbands. Frequently, we would be reminded of successful former Bloemhof pupils, such as Mrs Annetjie Marais, whose claim to fame was that her husband, Piet Marais, was a member of parliament. In years to come, when I became an mp, this would make me smile, even though Bloemhof was not impressed with my activities.

And yet, perhaps inadvertently, Miss Coetzee and Bloemhof helped me search for more from life. The fact that we were a girls-only school and had only female teachers meant that we had to do everything. There were no boys to carry things, nor were they given preference in speaking orders or glorified in sport. There were no romantic or sexual distractions. Miss Coetzee would frustrate us endlessly with her little sayings in assembly, such as: ‘Always fill your mind with beautiful thoughts’ or ‘Remember that CL [the car registration code for Stellenbosch] stands for “Christian Ladies”.’ Yet some of her frequently repeated quotes embedded themselves into my subconscious. Years later, I still remember: ‘Even a dead fish can swim with the stream’ and ‘There is not enough darkness in the world to destroy the light of one little candle.’ Wise words.

I focused on academia and ballet. I was now doing up to three hours a day of ballet lessons, and I would get up at around 5am to practise for two hours before school at the barre my parents had installed for me in the playroom. From an early age, my sisters and I had a Calvinist approach to work and life instilled in us. If you wanted to get somewhere in life, you had to work hard. To work harder than anyone else was the only way to get anywhere, and in addition, it was virtuous. To be idle was no good.

I still find it difficult to watch television without doing something else at the same time. Television time was strictly controlled; even at high school, we were not allowed to watch TV after 8pm. So we practised and worked hard. These teachings were reinforced by the church, where I spent most of my free time. The doctrine of the Dutch Reformed Church was based on fear and was fervently anti-Catholic. I did my best to follow the instructions and teachings.

Naturally, being in an all-white church, school, ballet group and neighbourhood isolated us all to a great extent from what was going on in the rest of the country. The only impact we felt from the unrest elsewhere was the regular drills at school in case of a terrorist attack, which we all knew really meant a ‘black attack’. In such an event, an alarm would go off, and on the teacher’s command of ‘Val plat!’ we would have to get down under our desks or hide in cupboards or storerooms. We practised this drill frequently. We were also taught to identify terrorist explosive devices, with examples of various bombs and limpet mines exhibited throughout the school. There was a weekly instruction of ‘Jeugweerbaarheid’ (Youth Preparedness), which, depending on the teacher, could be more or less ideologically driven. As instability grew and riots became more frequent in the 1980s, we were rarely aware of them, since the media were tightly controlled. Apartheid was very successful in what it set out to do – namely, to keep us apart.

During this time, however, Miss Coetzee gave a long lecture in assembly against ‘the black terrorists who were causing all the riots in the townships in Cape Town’. Even though I knew very little about what was going on, I instinctively revolted against her racist language and crude generalisations. As we left assembly, she called me aside and asked me why I had frowned during her speech. I said I did not like the way she had spoken and was sure that things were more complicated than she had made them out to be. I thought I could see the smoke coming from her ears as she turned red with anger. She pointed her long-nailed, crooked finger at my face and poked at my nose while rhythmically saying, ‘Be very careful [poke] young lady [poke]. Very [poke], very [poke] careful [poke, poke].’ I became equally annoyed, and turned around and walked away.

If any of the teachers did not agree with the school’s philosophy, they kept it to themselves, fearful for their jobs. But there was one teacher who made a big impression on me and my fellow students. Letitia Snyman had spent many years in England before returning to South Africa to be close to her elderly parents. She taught English and was in a different league from the rest of the teaching staff. Although she never explicitly voiced any political opinions in class, we all knew she thought differently. She gave us additional English texts to read, like Animal Farm and Lord of the Flies, and insisted on us expressing opinions on difficult and moral questions.

She did not judge our conclusion as long as it was well thought through and well argued. She must have had a difficult time at Bloemhof, but later became the principal of the adjacent English Girls’ School: she guided that school through a process of racial integration, and also turned it into a top all-round school. She made us think, and, contrary to the rest of our education, insisted that we were not only allowed to question things around us, but in fact had an obligation to do so.

In my final year of school, I was elected chairperson of the Christian Student Association. This was not of much consequence, except that I invited a well-known theology student, Wilhelm Verwoerd, to address us at our annual meeting. He brought his girlfriend along. Apart from thinking that he had appalling dress sense, I was quite impressed with the talk, although I was completely unaware that he was a grandson of the former prime minister.

I had two boyfriends at school, but being very religious, we only ever held hands and kissed. In fact, even dancing was frowned upon, so although I loved ballet, I never danced socially until the school’s farewell ball, with my boyfriend of the time.

I continued to be completely absorbed by ballet. I was good at it, and danced the lead in many performances. I wanted nothing more than to become a professional dancer. The teachers felt I had enough talent to make a success of it, but my mum was completely opposed to it. Given her personal history, not getting a degree was not an option for me. She made that clear for years, although, when she saw how ecstatic I was every time I came off stage, her position gradually softened. Eventually she gave in and agreed that I could go to the University of Cape Town to study ballet. But as soon as she agreed, I started to have doubts of my own, and one day, after taking the bandages off my bleeding toes, I had had enough and decided to go and study at Stellenbosch. For years I would wonder if I did the right thing, and I still miss the thrill of doing a perfect arabesque or landing a pirouette.