Читать книгу House of Beauty: The Colombian crime sensation and bestseller - Melba Escobar - Страница 6

2.

Оглавление‘From a young age, black women straighten their hair with creams, with straighteners, with hairdryers; we chew pills, wrap it up, pin it down, apply hair masks, sleep with stocking caps in place, use a silicone sealer. Having straight hair is as important as wearing a bra, it’s an essential part of femininity. A woman’s got to do what a woman’s got to do, she has to pluck up her courage, use as many clips as it takes. She has to be prepared to endure painful tugging, sometimes for hours on end. It’s wasteful and uncomfortable, but there’s no getting away from it if you want to achieve the silky straight look,’ said Karen in her low, rhythmic cadence.

‘And little girls, do they have to do it too?’

‘If they’re really little, no, but young ladies – eight, nine – then sure, they all straighten their hair, of course,’ she said as she removed the wraps.

Karen told me that when she arrived here, she liked the city. And yes. Many find it beautiful. Many are drawn to the mild sadness that distinguishes it, a sadness that is occasionally interrupted by a bright Sunday morning as radiant as it is unexpected.

She left her four-year-old with her mother in Cartagena and came to Bogotá. A former colleague had started up a beauty treatment centre in the Quirigua district, and she offered her a job. She promised her mamá she would send money for Emiliano each month, which she does. Her mamá lives in a house in the San Isidro neighbourhood with Uncle Juan, a confirmed bachelor who is in poor health. They live mainly on her uncle’s pension, his due for the thirty years he worked in the post office, and on the money Karen sends.

Karen grew up listening to vallenato, bachata and, when she was old enough, champeta. Her mother, barely sixteen years older than Karen, was crowned Miss San Isidro once, which she thought was a sign she would escape poverty. Instead, she ended up pregnant by a blond guy – a sailor, she assumed – who spoke little Spanish. After love paid Karen’s mother that furtive visit, the honey-coloured girl was born, and she shared not only her mother’s surname, but her beauty and her poverty too.

Doña Yolanda Valdés sold lottery tickets, sold fried fare, was a domestic worker, bartended in the city. Finally, she devoted herself to her grandson, resigned to her arthritis and to the fact that she gave birth to a girl instead of a boy. At forty years of age she was practically an old woman.

Doña Yolanda’s love affairs resulted in two more pregnancies, boys both times, but her luck was such that one was born dead and the other died after just a few days. Yolanda Valdés said the women in her family were cursed. An evil spell fell over them when they least expected it, and condemned them to inescapable solitude.

Karen remembers the seven o’clock Mass on Sundays and waking to the sound of canaries singing. She remembers fish stew at Los Morros beach and taut skin and the dizzying white lights that speckled her field of vision when she floated for a long stretch.

In time, our ritual of shutting ourselves away in that cubicle, sheltered by her youth, the cadence of the sea and the force of her soft, firm hands, became for me a need as ferocious as hunger.

From the moment I first set eyes on her, I wanted to know her. Gently, tenderly, I asked her questions while she moved her fingertips over my back. That’s how I found out that she arrived in Bogotá in January 2013, the sunny time of year. First she stayed in Suba, in the Corinto neighbourhood, where a family rented her a small apartment with a bathroom and kitchenette for 300,000 pesos, including utilities. She earned the minimum wage. At the end of the month she didn’t have two pesos to rub together, so couldn’t send anything home. On top of that, the neighbourhood was unsafe and she lived in constant fear. On the same morning that a drunk man shot two people for blocking a public road during a family get-together, Karen made up her mind to find another place to live.

She moved to Santa Lucía, to the south, near Avenida Caracas, but now had to cross the entire city to reach the salon where she worked.

When a colleague mentioned that an exclusive beauty salon in the north was looking for someone, Karen secured an interview. It was the beginning of April. The city was waterlogged from downpours. Karen had been in the new house barely a couple of weeks and took the deluge as a sign of abundance.

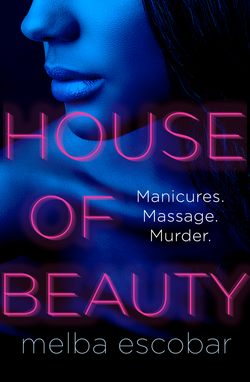

House of Beauty is in Zona Rosa, Bogotá’s premier shopping, dining and entertainment district. From the outside, the white edifice suggests an air of cleanliness and sobriety: part dental clinic, part fashionable boutique. Once through the glass doors, you are transported to a land of women. The receptionist behind the counter greets you with her best smile. Several uniformed employees, polished and smiling, are in the display room offering creams, perfumes, eyeshadow and masks in the best brands. On the coffee table in the waiting room are piles of magazines.

Karen remembers arriving on the fifth of April at around 11.30 in the morning. As soon as she crossed the threshold, she breathed deep an aroma of vanilla, almonds, rosewater, polish, shampoo and lavender.

The receptionist, whom she would soon have the chance to get to know better, looked like a porcelain doll. An upturned nose, large eyes and those full, cherry-coloured lips. As she headed past her for the waiting room, Karen wondered what lipstick she used.

At the back, there was a large mirror and two salon chairs where a couple of women did eyebrow waxing, make-up and product testing. They were all wearing light-blue slacks and short-sleeved blouses in the same colour. They looked like nurses, but well-groomed and made up, with impeccably manicured hands and waspish waists. The name badge on one perfectly bronzed woman told Karen her name was Susana.

The cleaner also wore a blue uniform, but in a darker hue. She came over to offer Karen a herbal tea, which Karen accepted. She saw the tropipop singer known as Rika come in. She was dark and voluptuous with an enviable tan, possibly older than she looked. She wore sunglasses like a tiara, had a gold ring on each finger and lots of bracelets. Like Karen, she announced herself at the reception desk and then took a seat beside her with a magazine.

‘Doña Fina is expecting you, you can go in,’ said the receptionist.

‘Thank you,’ said Karen, making sure to pronounce all her consonants to hide her Caribbean accent.

She went up a spiral staircase, passing by the second floor to reach the third. To her right, three manicure stations, four for eyelashes. In the middle, four cubicles and, at the back, to the left, Doña Josefina de Brigard’s office. Karen approached the half-open door and heard a voice beyond it telling her to come in. In the middle of an inviting room, with skylights that revealed a bright morning, stood a woman of uncertain age. She was dressed in low-heeled shoes, khaki pants, a beige blouse and a pearl necklace, with an impeccable blow-dry and subtle make-up.

‘Take a seat,’ she said in a low voice.

Doña Josefina watched Karen walk to the chair on the other side of the only desk in the room. She looked her up and down with her deep green eyes, raising her eyebrows slightly.

Then she looked straight into Karen’s eyes. Karen bowed her head.

‘Let me see your hands,’ she said.

Karen held them out, a child at primary school all over again. But Doña Josefina didn’t get out a ruler to punish her. She let the young woman’s hand rest on her own for a moment, then put on her glasses, examined the hand with curiosity, repeated the operation with the left one and asked her once more to take a seat.

She, in contrast, paced around the room. If I had that figure at that age, I wouldn’t sit down either, Karen thought.

‘Do you know how many years House of Beauty has been running?’

‘Twenty?’

‘Forty-five. Back then I had three children. I’m a great-grandmother now.’

Karen looked at her waist, delicately cinched by a snakeskin belt. Her pale pink nails. Her almond-shaped eyes. Her prominent cheekbones had something of the opal about them, pale and gleaming. The woman standing before her could have been a film star.

‘House of Beauty and my family are all I have. I’m exacting, and I don’t make concessions.’

‘I understand,’ said Karen.

‘Yes, honey, you have an I-understand face. You went from an exclusive salon in Cartagena to a run-of-the-mill one in Bogotá. Why?’

‘Because I earn more here than there, or at least that’s what I thought when I left the coast.’

‘It’s always about the money.’

‘I have a four-year-old.’

‘So does every other young woman.’

‘A four-year-old?’ Karen said.

‘I see you’ve got a sense of humour,’ said Doña Josefina, abruptly going back to the formal ‘usted’. ‘This is a place for serious, discreet women who are willing to work twelve-hour days, who take pride in their work and understand that beauty requires the highest level of professionalism. With your gracefulness, I’m positive you could go far here. You’ll see: our clients may have money, some of them a lot of money, but much of the time they are tremendously insecure about their femininity. We all have our fears, and as we start ageing, those fears grow. So, here at House of Beauty we must be excellent at our jobs, but we must also be warm, understanding, and know how to listen.’

‘I understand,’ said Karen automatically.

‘Of course you don’t, child. You’re not old enough to understand.’

Karen kept quiet.

‘So, as I was saying, don’t be too quick to answer; if they want to chat, then you chat; if they want to keep quiet, you should never initiate a conversation. Requesting a tip or favours of any nature warrants dismissal. Answering your phone during work hours warrants dismissal. Leaving House of Beauty without seeking prior permission warrants dismissal. Taking home any of the implements without permission warrants dismissal. Holidays are granted after the first year; pension contributions and healthcare are at your own expense. Same with holidays, which are in fact unpaid leave, and can never exceed two weeks, bank holidays included. The files, creams, oils, spatulas and other implements are at your own expense, too.’

‘Can I ask what the salary is?’

‘That depends. For each service, you receive forty per cent. If you’re popular and our clients book a lot of appointments with you, after a few months you could earn one million pesos, including tips.’

‘I accept.’

Doña Josefina smiled.

‘Not so fast, honey. This afternoon I’ve got two more interviews.’

Karen found it fascinating that an elegant woman with a well-bred air could switch so easily between being formal and informal.

‘Then I would just like to say that I’m very interested,’ she said politely.

‘We’ll have an answer for you in a couple of days.’

As Karen was leaving, Doña Josefina stopped her.

‘And one more thing. Who doesn’t like a Caribbean accent? Don’t try to hide it. No one, not one single soul in this country or any other, likes the way we Bogotans speak.’

A week later, Karen was part of House of Beauty. ‘If I had been put in the eyebrow, make-up and eyelashes section, I’d have had trouble competing with Susana,’ she told me. Each woman had her strengths, and soon Karen was queen of the second floor. She was assigned cubicle number 3 for facials, massages and waxing. Her beauty, care and professionalism made her a favourite, especially for waxing. She discovered that when Bogotan women came for a Brazilian, it was almost never on their own initiative but because their husband, boyfriend or lover had asked. She told me about her clients and her colleagues at House of Beauty. That was how the name Sabrina Guzmán came up.

Karen knows who has a birthmark on her hip, who suffers from varicose veins, whose breast implants give her trouble, who is about to split up, who has a lover, who is cheating, who is travelling to Miami for the long weekend, who was diagnosed with cancer last week, and who has daily waist-slimming massages without telling her husband.

What’s confessed in the cubicle stays in the cubicle, same as happens on the couch. Like the therapist or confessor, the beautician takes a vow of silence. Of course, she would later come to tell me things she’d been told in the cubicle. But that was different.

On the treatment table, as on the couch in my line of work, a woman can stretch out in surrender. She obeys the SWITCH OFF YOUR PHONE sign and enters the cubicle ready to disconnect. For fifteen minutes, half an hour, maybe more, she is isolated from the world. She tunes out everything but her body, the silence or the intimate conversation. Often the confidences shared in the cubicle have never been told to anyone before.

Sabrina Guzmán arrived one Thursday in the middle of a downpour, barely half an hour before closing. She reeked of brandy, her hair was soaking wet, and she was in her school uniform. She said her boyfriend was taking her to a romantic dinner and the night would conclude in a five-star hotel. As far as Karen understood, it was the same boyfriend who had wanted to sleep with her on two previous occasions, but hadn’t done the honours because, in Sabrina’s words, she wasn’t as smooth as an apple.

He was coming to Bogotá for two days, so he had to make the most of it. Sabrina didn’t explain what he’d be making the most of, but Karen assumed she meant deflowering her. The waxing was torture for them both. Sabrina complained too much, and when Karen saw a few drops of blood, she felt suddenly cold.

When the girl left, Karen stared at that sprinkle of blood on the treatment table cover and wondered how to get rid of it. She tried water, soap and ammonia, but only managed to smudge the stain to a pale rose. That stain would have to accompany her for the rest of her days working at House of Beauty.