Читать книгу Heart and Soul - The Emotional Autobiography of Melissa Bell, Alexandra Burke's Mother - Melissa Bell - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

STAYIN’ ALIVE

ОглавлениеSitting in a bed for four or five hours every couple of days, having the blood slowly and methodically sucked out of my body by a machine, cleansed of all the poisons that have built up and then pumped back in, gives me a lot of time to think. It gives me a chance to remember the dreams I started out with in life and the amazing places that they have led me to.

Everyone starts out with dreams, hopes and ambitions, but they don’t always work out quite how you expect. I guess it’s like John Lennon once said, ‘Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.’

There’s lots of other stuff to think about too. Not just the dark, dramatic, frightening chain of events that have come about inside my body and my DNA, leading to my being here in this bed, surrounded by machinery and screens, but the fabulous moments as well, like when I was standing on a stage singing strong and proud to millions of people around the world, or when I first heard my voice coming back to me off a little piece of black vinyl or out of my mother’s bedside radio. I think about the future a lot too, and everything exciting that it holds for my family. If there wasn’t so much to look forward to, perhaps it would be harder to get through the bad days, harder to make the effort needed to keep on living.

Today I’m going to be stuck in this bed for the full five hours because I was a little naughty yesterday and ate two nectarines. I knew I shouldn’t be doing it, even as I was slipping them in between my lips and enjoying their taste and the soothing juice as it slid down my throat. In my heart, I knew that they would try to poison me, but the first one looked so tiny and innocent I told myself it couldn’t possibly do me that much harm. And when I actually bit on it, it was so soft and so sweet and delicious the memory wouldn’t go away and I just couldn’t resist the temptation of having another one a few minutes later.

Even after all I have been through, I still wasn’t able to stop myself and the moment I’d finished them I knew I was going to have to pay the price today. When I arrived on the ward this morning, I had to own up to the nurses and ask them to make sure that the potassium which I knew the succulent little fruits had deposited in my blood was all safely removed by the machine; otherwise, if it stays there, it will stop my heart from beating. My whole life now has to be about resisting temptations from all the seemingly innocuous everyday things that are trying to kill me, like they killed my mother and my grandmother before me, and maybe many other women in my family over the centuries.

Three days a week, I have to go through the same tedious ritual, often lying in exactly the same hospital bed, with my hair scraped up inside an unflattering plastic cap. If I stopped coming for these sessions on the machine, I would almost certainly be dead within a week. You can’t live without your kidneys – if your kidneys fail, you have to have dialysis to cleanse the blood and perform the function your kidneys usually would. The machine that stands beside the bed is my best friend and I have to remind myself of that whenever I am tempted to hate it. It is only because of that machine that I am here and able to enjoy the excitement of watching all our family dreams come true.

Some people decide that the pressure and worry of dialysis, coupled with the frequent exhaustion and other symptoms of kidney failure, is all too much and they deliberately give up coming to the clinic to be hooked up to the machines. They literally ‘sign off’ from the treatment, knowing that by doing so they are choosing to end their lives the moment they scribble their signature on the hospital form. I suppose it isn’t exactly the same as committing suicide, more a question of ‘letting nature take its course’, but the result is still the same. It ends all hope of things ever getting better.

Kidney failure is not a painful death apparently, apart maybe from the terrible itching you get under the skin every time you eat anything, but the doctors can give you drugs to relieve that. Without the support of your kidneys, your body simply closes down. But I still don’t understand what brings people to make that decision. I would never want to do that, never want to end my life deliberately just to avoid these sessions. It may be boring and an inconvenience to have to lie here for hours on end, but surely it’s better than dying. When I think back to the wonderful, overwhelming highs that I have experienced in my life, I wouldn’t want to risk the chance of missing out on any more that the next few years might hold in store for me. Life has always been a struggle, but I believe the rewards are more than worth the fight.

There is so much I want to live for. I’ve produced four beautiful children and brought them up on my own and I want to see how they turn out. Our lives are too exciting and too full of possibilities for me to even consider giving up on it all now. I also like to flatter myself that they still need to have me around, at least some of the time.

Music was the first great love of my life and it has stayed faithful to me ever since I first discovered it. I can still put on earphones and listen to wonderful songs and I can still get up on a stage or go into a studio and sing whenever I’m asked, filling my lungs with air and loving the sounds that come out of my mouth. Music alone is reason enough to stay around on this earth as long as possible.

You can fit most things you want to do around dialysis sessions. I won’t even let the need to be near a dialysis machine stop me travelling when I want to. I’ve learned that if you organise yourself carefully you can book in for sessions on a machine in most other countries, particularly in Europe, as long as you don’t mind getting stuck into all the necessary paperwork. Basically all the authorities want to know is that you don’t have HIV, which I don’t, and after that it’s just a question of emailing the right papers to the right people to make sure you have a bed reserved in a clinic somewhere at the moment you need it.

A few years ago, I was contacted on MySpace by an international soul band based in Germany, called T-MC, asking if I would sing with them. I went over to see them and we got on well. I recorded a song for their album and, as so often happens among people in the music business, they have gone on to become longstanding family friends. I’m going over there for the launch of the album next week. It will be my fourth visit and I’ve found a dialysis clinic I can go to for three mornings of treatment during my stay, which is right next to the hotel they’ve booked me into. I’ll be able to walk round in my pyjamas if I want to. It would have been so easy to tell them that I couldn’t go, that it was all too difficult, that I was too exhausted, but then I would miss a really great opportunity and, as long as I can still walk and breathe, laugh and sing, I want to enjoy every moment of my life to the full.

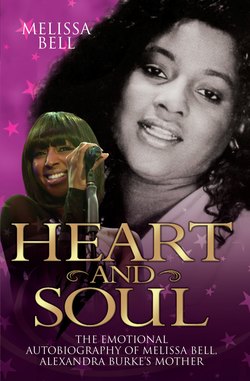

Officially I am still down on the records here in the hospital as ‘Euphemia Burke’, but everyone on the ward knows me as Melissa. Burke is my married name, so I prefer not to be called by it too often, even though it’s the kids’ name too. I love my kids more than anything and I wouldn’t have wanted to miss the experience of bringing them into the world and watching them grow into beautiful, talented young adults, but if I could have managed it without marrying their father it would have saved us all a great deal of heartbreak. Being known by my husband’s family name is an annoyance because that isn’t really who I want to be and because he and his parents have been out of my life for so many years now. I prefer being called Melissa Bell.

I first became known as Melissa by accident when I was still at school. Some of the less nice kids kept chanting ‘Euphemia’s got Leukaemia’ at me, so I started using my middle name, Imelda, instead. That led to my friends calling me Mel, and once other people had forgotten that I had ever been called Euphemia they just seemed to assume that ‘Mel’ was short for Melissa. I preferred it to Imelda so I didn’t bother to correct them and before long it had become my name. That’s how easily I became someone else.

The surname ‘Bell’, which I use most of the, time now was suggested by a friend of mine when I started singing professionally and needed something catchy to go with Melissa. That’s how Melissa Bell came into existence, but Euphemia Burke still lives on in the records of the National Health Service and I never bother to correct the new nurses who think it is the best thing to call me. ‘Euphemia’ means ‘to speak well’ apparently, and comes from the Greek word for ‘good’. St Euphemia was an early martyr who was burned at the stake. That’s all very well, but to me it will always sound like ‘leukaemia’, with those childhood voices forever chanting in my memory.

So there are only two ways for any of us in this ward to come off these machines: one is to give up on life, which is not going to happen. The other is to have a kidney transplant, which means finding a match. That is never easy, and it is even harder when you have a blood group as rare as mine. I have the blood of so many different races coursing through my veins that there aren’t too many people to match up with, and most of the ones who do exist live deep in the tropical mountains of Jamaica and aren’t exactly clamouring to give up their body parts to some woman from a council estate in north London any time soon.

I’m not the only one with this problem by any means. Just one person in this ward has been able to have a transplant in the year since I started coming here, whereas I know of a couple who have simply given up hoping and have signed off to die.

The daily routine here is always the same. They hook us up to the machines on a ‘first come, first served’ basis, so I always want to be the first in the queue when they open the doors to the clinic at seven in the morning. I want to make sure that I will be the first to finish, when there is still at least half the day left for me to do something. It would be all too easy to surrender the whole day to the treatment and end up with no time for anything else at all. Over the last year I would have missed some of the greatest moments of my life if I had allowed the treatments to last all day.

Sometimes I don’t even bother to get dressed before coming in, just climbing out of bed, pulling on some light pyjamas, running downstairs to the car and driving to St Pancras Hospital, desperate to get there before the ambulances arrive and start disgorging all the other patients they have picked up on their way in.

There are about a dozen beds and machines in the ward that I go to, and you get to recognise the same tired, familiar faces as they start to arrive each morning. Not many live as close to the hospital as I do, so I am nearly always there before anyone else. We all know one another well enough to nod ‘hello’ and ‘goodbye’ a few hours later, but for some reason people don’t seem to want to talk while they’re undergoing their treatment. It’s as if they have entered their own internal worlds, lying on the beds, the machines patiently ticking and turning and beeping beside them. I would love to chat, just to help pass the hours, but I can see that others would not welcome it, so I keep myself to myself, just like everyone else. The upside of that is that it gives me all this time to think. Everything has happened in such a rush over the last few months and in a funny way it’s helpful to have some quiet time to try to work it all out and get some perspective on all the excitement and glamour, all the emotions and the demands. Everyone benefits from taking a little time to stop and think now and again.

Digital displays on the machines tell me how much time I have left before the job is done, how much fluid my body still has to get rid of. I spend my time thinking, reading, dozing. I listen to my headphones. I usually like to have my radio tuned into LBC, a local London talk station. Music has been such a huge part of my life and for many years I hardly did anything else but listen to it and sing along to it, but now I find I like to learn about other things as well. I like to try to find out a bit about how the world around me works, to try to make a little sense out of what has happened to us.

My great love affair with music hasn’t dimmed, but there is room in my head for other things now as well. I like reading biographies of successful people, many of them in show business or the recording industry – finding out how they achieved what they did, comparing their experiences with mine, imagining how I might be able to do the same as they did, either for myself or for my children. We have had some fantastic successes already, but that doesn’t mean we couldn’t be doing it better, couldn’t climb higher and have even more great experiences.

Now and then the dialysis machine will clog up, or I will make too big a movement and it will react badly to the disturbance of the tubes, making me jump back to reality from wherever my mind has wandered, angrily bleeping at me to reset it, which I can do for myself now without always having to trouble the overworked nurses. I used to feel a surge of panic whenever one of the alarms went off, but I’ve grown used to them over the months. I know it is just part of the unpleasant routine.

They give me a drug to stop my blood from clotting during the process because apparently that can happen sometimes. It seems like nothing in my body can be relied on to do the job it’s meant to do any more. The machines here are second-hand ones, donated to us by Barnet Hospital and refurbished. We are very grateful to have them. If only there had been more machines around 20 years ago, maybe my mother would not have had to die so early and so uncomfortably. She was a good woman and she didn’t deserve any of what she had to go through. But I guess none of us does, and if you want your share of the lucky breaks you have to take the bad luck that comes along with them.