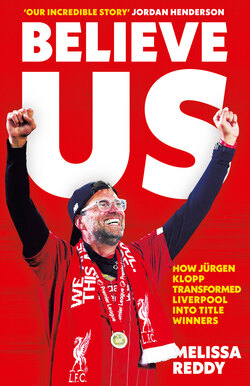

Читать книгу Believe Us - Melissa Reddy - Страница 9

2 The Perfect Fit

Оглавление‘From tomorrow I will be the Liverpool man 24/7.’

Jürgen Klopp

‘We’re hitting for the cycle,’ John W Henry smiled to FSG chairman Tom Werner and its president Mike Gordon. In baseball, the terminology refers to the achievement of one batter recording a single, double and triple hit as well as a home run in the same game. It is uncommon and one of the most difficult feats to accomplish in the sport.

As the trio took in the East Manhattan skyline from a 50-storey skyscraper housing the offices of law firm Shearman & Sterling on Lexington Avenue, they were primed to swing big in a meeting they believed had the power to reshape not just Liverpool FC but the football landscape.

Henry was equating being on the cusp of hiring the perfect manager for the club — an incredibly complex criteria to meet — to hitting for the cycle. No fanbase deifies the main man in the dugout as vociferously as Liverpool’s: through banners, in song and the manner in which they are tattooed to the very soul of the institution. It’s a phenomenon that stretches back to Bill Shankly’s appointment in 1959, with the Scot transforming a club in the Second Division into a ‘bastion of invincibility’ during his 15-year dynasty.

Equally, no fanbase are as demanding of what they want in their leader. At Anfield, the requirements stretch well beyond what a CV reads or being tactically excellent. You need to win, connect with supporters and represent the essence of Liverpool on a cultural, political and spiritual level. In summary, a top manager must also operate as a man of the people while illustrating he is bigger than the job, greater than the expectations and unwavering in his handling of the fiercest criticism.

In New York on 1 October 2015, FSG were confident they were going to hire that very figure. A magnetic individual who had the proven capacity to galvanise, rejuvenate and deliver sustainable success to a club, while also having a lasting impact on the place and its populace.

‘It’s the right guy at the right time,’ Gordon noted. But the owners had selected the wrong choice of day for their first face-to-face interaction with Jürgen Klopp. The meeting coincided with the annual gathering of the United Nations general assembly, which gridlocked New York. The German’s journey from JFK Airport to Lexington Avenue took six hours in snaking traffic, and while it was unwelcome, it didn’t diminish his ‘highest enthusiasm’ for the opportunity to outline his vision for Liverpool.

Long before Klopp stepped into the building, the job was his. It was not an interview, rather a confirmation of what FSG already knew about the two-time Bundesliga winner courtesy of a call, a Skype conversation, and crucially, a detailed 60-page dossier on his way of working. Compiled by Liverpool’s esteemed head of research, Ian Graham, and Michael Edwards, who was technical director at the time, it evaluated everything from the manager’s training sessions, reaction to setbacks, achievements in relation to his resources as well as his interaction with staff and players through first-hand testimony from his former clubs Mainz and Borussia Dortmund. The more Liverpool drilled into Klopp’s methodology, the greater their conviction was that he could unify the core areas of the club and elevate it.

Beyond the comprehensive document, FSG knew he was their guy because they had previously pursued him twice. Each time they sought a manager, he stood out and tallied with their long-term thinking. Towards the end of 2010, as Roy Hodgson was scraping through a painful spell at Liverpool’s helm that would eventually span only 31 games in charge, the group used a third party to ascertain whether Klopp would consider leaving Dortmund to move to Anfield. It was no surprise the answer was negative, given he was successfully re-establishing BVB as a Bundesliga and European force while they played irresistible, high-pressing football.

A year later, another tentative approach was made when club legend Kenny Dalglish, Hodgson’s replacement, was released from his second stint at Liverpool. ‘I have been made aware of interest in England, and it is an honour to be linked with big clubs in the Premier League,’ Klopp said, before emphasising, ‘I love it here [at Dortmund] and have no intention of changing clubs.’

Naturally, Liverpool were not the only English team trying to secure the elite manager, who had halted, at least temporarily, Bayern Munich’s monopoly on being Germany’s best. Winning back-to-back Bundesliga titles and bulldozing opponents in the Champions League, where Dortmund reached the final in 2013, meant that interest in Klopp ballooned — especially 30 miles away in Manchester. While Dalglish’s successor as Liverpool manager, Brendan Rodgers, was overseeing poetry in motion on Merseyside in early 2014 with a Luis Suarez-powered offensive line taking the club close to the title, David Moyes was horribly floundering at Manchester United. Sir Alex Ferguson’s successor was well out of his depth and urgent action was necessary to remedy the club’s demise. Their executive vice-chairman, Ed Woodward, scheduled a chat with Klopp in Germany to sell him on making the switch to Old Trafford.

The BVB trainer hugely admired Ferguson’s achievements and the manner he went about establishing United as a global juggernaut, which is largely why he agreed to the encounter. Woodward’s pitch, however, was the antithesis of what would appeal to Klopp. He spotlighted their financial might and offered an Americanised picture of blockbuster names and entertainment while likening United and Old Trafford to the game’s Disneyland.

Klopp, a football romantic who feeds off emotion and who counts time spent on the training pitches as more fundamental than transfers, was turned off.

That came as no shock to Christian Heidel, the former sporting director of Mainz. He has a three-decade relationship with Klopp and was the one who offered him the chance to instantly progress from being a player to the club’s manager. ‘Emotionally powered’ is one of the core descriptors he uses for his friend, who is also a ‘fighter’ and ‘builder’. Heidel knew Klopp’s powers could only be properly unleashed at places that resonate with his own personal experiences. Being at United and having an unlimited budget would jar with a life shaped by scaling adversity and making the most out of little.

Klopp’s formative years in Glatten, a tiny but picturesque town in the Black Forest, were simple. His late father, Norbert, who had been a promising goalkeeper and earned a trial at Kaiserslautern as a teenager, worked as a salesman specialising in dowels and wall fixings. He was a ruthless competitor, extracting the maximum from his son by never taking it easy on him, whether it came to skiing, tennis, football or sprints across the field. Norbert impressed on him that it wasn’t worth doing anything without full dedication. He taught his son that ‘attitude was always more important than talent’, promoted a ferocious work ethic and schooled him in the art of resilience.

Klopp junior, a Stuttgart fan, had an unsuccessful trial with his boyhood club and did not become a professional footballer until he was 23. In the interim, he turned out for Pforzheim, Eintracht Frankfurt II, Viktoria Sindlingen and Rot-Weiss Frankfurt while working part-time in a video rental store and loading lorries. He juggled that with taking care of his toddler, Marc, while also studying for a degree in sports business at Goethe University Frankfurt.

‘Life took me a few places and gave me a few jobs,’ Klopp noted. ‘It wasn’t about where I could be, but about doing what I had to do, because I was a young father and needed to provide.’ After finally landing a pro contract with Mainz in 1989 as an industrious but technically-limited striker, Klopp still took steps to invest in his future for the benefit of his family. Earning just £900 a month, he signed up to the legendary Erich Rutemöller’s coaching school in Cologne. Twice a week, he would undertake the 250-mile round trip to enhance his tactical understanding of the game.

Klopp also sponged off Wolfgang Frank, the late Mainz coach who was inspired by Arrigo Sacchi’s Milan. He would spend hours talking to him about systems and the secrets to overpowering better resourced opponents. ‘Under Wolfgang Frank, for the first time in my career, I had the feeling that a coach has a huge impact on the game,’ Klopp would reveal. ‘He made us aware that a football team is much more independent of the class of individual players than we thought at the time. We have seen through him that it can make life very difficult for the opponent through a better common idea.’

Frank was one of the first German managers of the era to shun using a sweeper, which was the norm, opting for a four-man zonal defence and a midfield diamond shape. He espoused high-pressing, attacking from inside, offensive protection and overloading the flanks — all hallmarks of Klopp’s teams to the present-day Liverpool.

Those tactics became the blueprint for Mainz in February 2001 when manager Eckhard Krautzun was sacked by the club on the eve of an away game and sporting director Christian Heidel called an emergency summit with senior players. It was decided at the meeting that Klopp, who had been converted to a defender from a striker, would undergo another transformation and become their new manager. The choice was unanimous and as with his playing career, the need to defy convention and recover from setbacks would be the driving force in his new managerial setup.

Klopp is unrivalled in dealing with massive disappointments and moulding them into both lessons and motivation. ‘Even when you don’t want defeats, when you have it, it is very important to deal with it in the right way,’ he said on looking back at his career in the game. ‘I had to learn that early in my life, especially my coaching life. We had so many close failures: like with Mainz not going up by a point, not going up on goal difference, then getting up with the worst points tally ever; Dortmund not qualifying for Europe, then losing a Champions League final. I am a good example that life goes on. I would have had plenty of reasons for getting upset and saying, “I don’t try anymore.”

‘Obviously, it is not easy to go through these moments, but it is easier to deal with it because it is only information, and if you use it right the feeling is good.’

That is pure Klopp. And it was why Hans-Joachim Watzke, Dortmund’s CEO, was convinced he would reject United’s offer. Their money-based pitch clashed with rather than complemented the manager’s make-up. In the second week of April 2014, Klopp told Watzke he’d be swerving the chance to take charge at Old Trafford. As he once summarised: ‘You can be the best in the world as a coach, but if you are in the wrong club at the wrong moment, you simply don’t have a chance.’

Enquiries from Manchester City and Tottenham would both also be rebuffed a few months later. A year after shunning United, however, Klopp’s circumstances at Signal Iduna Park changed considerably.

With Dortmund regularly ceding their greatest talents to European football’s apex predators — chiefly Bayern — they found that continuing to usurp their powered-up rivals in the Bundesliga was becoming too taxing. BVB’s results were no longer as good as their performances, with staleness and a sense of comfort creeping in. During a press conference that reverberated around the world on 15 April 2015, Klopp announced he would be leaving Dortmund at the end of the season. At the time, the club were 10th, 37 points behind Bayern. The city in Germany’s North Rhine-Westphalia was enveloped in sadness.

‘I always said in that moment where I believe I am not the perfect coach anymore for this extraordinary club I will say so,’ Klopp stated. ‘I really think the decision is the right one. I chose this time to announce it because in the last few years some player decisions were made late and there was no time to react.’

Fast forward five months and the atmosphere couldn’t have been more of a contrast in an expansive boardroom at the New York offices of Shearman & Sterling, where over the course of four hours, Klopp sketched his plan to restore Liverpool as a global and continental powerhouse.

He addressed the lack of an on-pitch identity, which would be the first facet to rectify, and also pointed out the importance of harnessing the emotional pull of the fans. From the academy through to the first-team operation at Melwood, Klopp outlined a blueprint for the club’s playing style and standards to be aligned. For Liverpool to have any chance of becoming a force again, he reasoned, they would have to operate as one formidable unit.

Mike Gordon remembers being ‘in awe’ of Klopp, not on account of his magnetic personality, but the substance of his strategy and the concise yet convincing way he delivered it in a second language.

It is why, just an hour into spelling out his vision, FSG told Klopp’s agent, Marc Kosicke, that their lawyers had begun drafting his contract of employment. When the juncture came to discuss personal terms at the end of the talk, the manager excused himself and took a walk through Central Park. As Klopp stood soaking in the sights of the Hallett Nature Sanctuary, it dawned on him that it was not the type of surveying he had originally contemplated after his break from football.

As a player, he was fascinated by watching how managers work — from implementing their philosophies to handling different personalities, balancing squad dynamics and drafting plans that extended beyond match preparation. Klopp had resolved to travel around Europe to absorb as much knowledge as possible from coaches when he hung up his boots. However, his immediate transition from pulling on a shirt for Mainz to becoming their manager paused that idea for seven years. Switching from the Opel Arena to Dortmund further shelved it for the same amount of time and now Klopp was fresh off a four-month sabbatical and about to become Liverpool manager.

That night, when he returned to his suite at the Plaza Hotel, he thought about how he wouldn’t change anything about his path, his choices or the timing of them, relating as much to his wife, Ulla Sandrock.

That same evening, Liverpool stumbled to yet another dispiriting draw at Anfield. The sound of the final whistle against FC Sion was met with booing for the third time in four games at the famed ground. Over in the Bronx, the Red Sox were defeated 4–1 by the Yankees, their greatest rivals. Yet those results couldn’t dilute FSG’s celebratory mood after finally securing the manager they had coveted since their takeover of Liverpool in 2010.

Back at Melwood, it was hard to escape the feeling that Brendan Rodgers’ time was running out. After Liverpool’s 1–1 draw at Goodison Park on 4 October that left them 10th in the league table, Rodgers was driving back home, when he received a phone call from Mike Gordon relieving him of his duties. News of his departure quickly broke, with Klopp’s status as the prime candidate to replace the Northern Irishman dominating the coverage.

Conversations at Liverpool’s training complex centred around him being so heavily linked with the job. ‘There was such a buzz and he was really high profile as well, which got the lads going,’ Adam Lallana recalls. ‘I remember us sitting in the canteen discussing that he ticks all the boxes for Liverpool. We weren’t going to outspend the likes of City, United and Chelsea and he wasn’t a big-money manager. He had a history of improving clubs by making the players he had better before building on that base. We spoke about games we’d seen of Dortmund, about things we’d read or heard about the gaffer and there was so much excitement around the place.’

Jordan Henderson was at the Bernabeu in April 2013 to watch BVB line up against Real Madrid in the second leg of their Champions League semi-final. Dortmund took a 4–1 advantage to Spain and lost 2–0 after late goals from Karim Benzema and Sergio Ramos, but still progressed to the climax of the competition at Wembley.

‘I was fortunate enough to go watch Dortmund against Madrid at the Bernabeu and I was really blown away by how clear their identity as a team was and how they controlled large parts of such an important game against a side with superior resources,’ Henderson says. ‘They lost the match, but it didn’t matter because they managed the tie well and you expect to be put under pressure by Real, especially when they’re at home and need to win, but Dortmund handled it.

‘When the gaffer was linked with us so heavily, I thought about the experience of that game and how positive everything around him and Dortmund felt. I was all in, and to be honest, a lot of the lads were desperate for it to happen. We knew his success with Dortmund was no accident and you could tell he was a special manager that could make a big difference.’

Carlo Ancelotti was the other candidate under consideration by FSG. While there was no questioning the Italian’s pedigree as a three-time Champions League winner, he did not generate enthusiasm around the club. The owners were put off by his focus on rebuilding through transfers and he seemed to be more of an overseer of good teams rather than a constructor of one. The majority of players were of the belief that Ancelotti would want to secure success through immediate investment instead of attempting to bring the best out of them over time. The staff, meanwhile, had heard from colleagues within the game that the man who led Real Madrid to their 10th European Cup could be detached and didn’t do much to uplift or inspire his squad or those behind the scenes.

‘With Ancelotti, the general feeling was he wouldn’t be the worst appointment because of his past accomplishments,’ remembers one member of Liverpool’s conditioning staff. ‘But it was like you had to explain to yourself why he would be good for the job. It was the opposite with Klopp — everyone was bouncing around the place at the thought of him becoming the new manager, because it just made so much sense.’

The bulk of Liverpool’s fanbase subscribed to the same thinking. They had been motioning on social media since 2014–15 for the German to take charge at Anfield under the ‘Klopp for the Kop’ tag and when it became clear he would succeed Rodgers, the boos and toxicity that marked the previous months were swept away by a groundswell of optimism.

There were three days between Rodgers’ sacking and the confirmation of Klopp’s appointment, which blitzed past in a blur. Klopp and Ulla had a flood of admin to take care of in a limited window, leaving little space to think about the job itself. ‘We left a country and our lives there behind, if you want, so we had to organise a few things,’ he explained. ‘It was quite busy those few days, quite busy, and it was not a lot about football.’

Knowing the importance of supplying the right message from the off, Klopp downloaded a language app to ensure his communication in English was effective enough. If he was hoping for some quiet time to work on his opening gambits to the press, Liverpool’s staff and his new players when he arrived on Merseyside, that plan was quickly stifled even before his departure from Germany.

A German television reporter buzzed Klopp’s home hoping to snatch an exclusive interview via the intercom on 8 October and he wasn’t disappointed. The broadcaster got one short sentence — ‘from tomorrow, I will be a Liverpool man 24/7’ — but that soundbite rippled across the world, with social media going into overdrive. Every bit of Klopp’s journey from his home in Germany to Liverpool’s John Lennon Airport was tracked, with the path of the private plane that was carrying him, his family and coaching assistants from Dortmund to Merseyside monitored in its entirety by over 35,000 people on Flightradar24.

As afternoon turned to evening, the roads leading to Liverpool’s Hope Street Hotel were swarming with supporters waiting to welcome him. ‘A party atmosphere’ is how Klopp recalls it and while he was pleased with the reception, it was no fun having his privacy impeded by the paparazzi who also stationed themselves close to the boutique accommodation used by Liverpool ahead of home matches.

As he settled into the Rooftop Suite, Klopp could hear the sound of shutters and see the flashes of light but couldn’t understand how it was possible for the photographers to get pictures into his room given it was so high up. Venturing out onto the private terrace, Klopp got his answer: they had made their way up adjacent buildings, hanging off the awnings to get their shot. He couldn’t understand it: he was just a football manager about to take charge of a new club. Granted, it was one of the biggest and most historic football clubs in the game, but he couldn’t fathom the fuss.

This was not just any managerial appointment though. It felt more symbolic. More than the start of a new tenure, the universal approval of Klopp offered a chance to unify the club, which would be imperative for success.

He was framed as a saviour, and in the hotel within walking distance of Liverpool’s two cathedrals, he signed a three-year contract worth £7 million per season. The inking of the agreement took place in the hotel’s Sixth Boardroom, with the steel outline of the new Main Stand at Anfield visible in the distance.

Klopp’s task extended beyond an on-pitch regeneration; he would need to oversee advancement off it too. While FSG were in no doubt he was the perfect fit to achieve that, the length of the deal — eschewing the usual five-year term — was rooted in realism rather than romanticism. Klopp had never lived outside of Germany, let alone managed in a different country or at a club as demanding and unforgiving as Liverpool. He was conscious of Ulla needing to settle and her happiness on Merseyside. It was a big adjustment on an individual level for both of them but also for their marriage.

The official announcement of Klopp’s signing was made by Liverpool at 9 pm, but by then the new manager was at an introductory dinner with Melwood staff. The expectation was that it was his chance to lay down the law and spell out his requirements for how things would work at the training ground going forward. Instead, it was the complete opposite.

‘The gaffer asked us to explain how things are, what we do, what he needed to learn,’ goalkeeper coach John Achterberg, who has been at the club since 2009, remembers. ‘He wanted to know more about us and how our departments worked and he listened to us. He asked us about the league, about rules, training schedules, how matchdays went. It was a good talk that showed us immediately that the gaffer was a team player. He didn’t come in with the attitude that he knew everything. He told us the club could only achieve our ambitions if we did it all together and with the highest standards.’

Later that evening, Klopp toasted his new life with Ulla, their sons Marc and Dennis and his long-term assistant Peter Krawietz at The Old Blind School bar and restaurant. As the pints flowed, so too did the pictures and requests for autographs. His disguise of a cap and black hoodie was certainly not enough to mask the identity of the most popular man in Liverpool.

If the full scale of excitement around his appointment didn’t dawn on Klopp yet, it would the next morning at his unveiling. Press from around the globe packed into the Reds Lounge at Anfield, with no place to stand let alone sit. A sea of cameras dominated the back section of the room, while photographers lay in the aisles and sprawled in front of the top table.

Considering the absence of preparation time as well as the fact he had to deliver his messaging in a second language, it was staggering how surgically and effectively Klopp addressed all his key constituents. He told his new Liverpool ‘family’ there was no need to pull together big speeches — if he believed in what he was saying, so too would the people he needed to.

The first important group to address was the players and as the media attempted to extract negativity about the squad he inherited, he countered, ‘I’m here because I believe in the potential of the team. I’m not a dream man, I don’t want to have Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi and all these players in one team. I want this squad, it was a decision for these guys. Now we start working.’

The recruitment staff that struggled to share common ground with Brendan Rodgers were relieved to hear Klopp shut down talk of trouble with transfer decisions being made collaboratively. ‘If two smart, intelligent, clever guys sit together on a table and you both want the same, where can be the problem? We all want to be successful,’ he said. ‘I’m not a genius, I don’t know more than the rest of the world, I need other people to get me perfect information and when we get this we will sign a player or sell a player.’

Klopp took aim at the British press too, imploring them not to portray him as a messianic figure. ‘Does anyone in this room think that I can do wonders?’ he asked before answering, ‘I’m a normal guy from the Black Forest. I’m the normal one. I hope to enjoy my work. Everyone has told me about the British press. It’s up to you to show me they are all liars!’

The most significant point of his opening press conference was targeted at everyone associated with Liverpool including the supporters. ‘History is only the base for us,’ Klopp said. ‘It is all the people are interested in, but you don’t take history in your backpack and carry it with you for 25 years. We have to change from doubters to believers. We can write a new story if we want.’

Those final two lines were simplistic, but that was by design. It was vital that the message was clear, easy to digest and share. The club’s silverware-lined history and the weight of expectation to deliver the league title had become a noose for previous managers. Klopp walked in and signalled his spell would not be dictated by it, which was different.

Adam Lallana remembers a few of the players watching the unveiling and being blown away by his courage to immediately tackle the ‘weight of the badge, the weight of history, the weight of waiting so long for the title’. He labelled it a ‘chest out’ moment for the group.

‘The gaffer could just see that pressure on everyone’s shoulders and that’s probably what shocked him the most when he first met everyone at the club, especially the players,’ Lallana says. ‘What was great and helped lift it is that he wasn’t just talking to us about that. He spoke to the media about that from day one. There would be games that I’d see him turn around in the dugout, screaming at fans saying, “Why the hell are you having a go? What are you complaining for?” He’d be correcting the behaviour of fans to be more supportive while the game was going on and — just wow! As players, it was huge to see that and there was a collective feeling of, “Oh my god, he’s got all our backs.” We could tell from the beginning we got in just the kind of personality that was needed to make Liverpool successful.’

Long before Klopp’s breakthrough in professional football with Mainz, he explored England via rail for a month. He swapped between sleeping in youth hostels, which offered free accommodation if he cleaned his room, and places that charged £5 as their bed-and-breakfast rate.

‘The weather was not too good, but I love this country,’ Klopp rewound. ‘I loved the language, it didn’t seem too difficult, and I was interested in meeting new people and learning their ways. I always knew I wanted to live here if it was possible. When I became a manager, it was clear that if there was a good opportunity in this country, to go for it.’

He did. And while Klopp’s initial contract in England was for three years to assess his adjustment, just eight months into his tenure he remarked to Mike Gordon that he could imagine being at Liverpool for the rest of his managerial career.

That information was relayed to John Henry and Tom Werner, with FSG getting on the phone to Marc Kosicke and thrashing out terms of a new six-year deal. Klopp was on holiday in Ibiza before ferrying over to Formentera, the smallest of Spain’s Balearic islands. On 16 June, as he celebrated his 49th birthday, he committed his future to the club until 2022. It was ‘the best present’ Klopp could have asked for as he was sure something special was brewing at Liverpool under his guidance. The team’s identity was unmistakable and their ascent had begun. They had lost the League Cup and Europa League finals — but getting to them was the most important takeaway. Their trajectory was clear.

In December 2019, Klopp agreed another extension, this time until 2024. Liverpool were champions of Europe at that stage, but the manager predicted it was only the beginning. ‘This is a statement of intent, one which is built on my knowledge of what we as a partnership have achieved so far and what is still there for us to achieve,’ he said.

Liverpool would go on to become the first team in British history to hold the European Cup, domestic league title, Club World Cup and the Super Cup simultaneously.

Hitting for the cycle indeed.