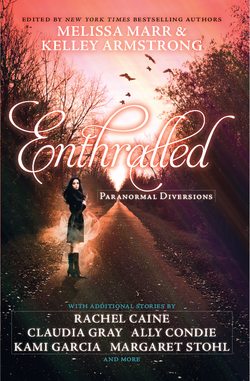

Читать книгу Enthralled: Paranormal Diversions - Melissa Marr - Страница 7

ОглавлениеRed Run by Kami Garcia

o one drove on Red Run at night. People went fifteen miles out of their way to avoid the narrow stretch of dirt that passed for a road, between the single stoplight towns of Black Grove and Julette. Red Run was buried in the Louisiana backwoods, under the gnarled arms of oaks tall enough to scrape the sky. When Edie’s granddaddy was young, bootleggers used it to run moonshine down to New Orleans. It was easy to hide in the shadows of the trees, so dense they blocked out even the stars. But there was still a risk. If they were caught, the sheriff would hang them from those oaks, leaving their bodies for the gators, which is how the road earned its name.

The days of bootlegging were long gone, but folks had other reasons for steering clear of Red Run after dark. The road was haunted. A ghost had claimed eight lives in the last twenty years—Edie’s brother’s just over a year ago. No one wanted to risk a run-in with the blue-eyed boy. No one except Edie.

She was looking for him.

Tonight she was going to kill a ghost.

Edie didn’t realize how long she had been driving until her favorite Jane’s Addiction song looped for the third time. Edie was beginning to wonder if she was going to find him at all, as she passed the rotted twin pines that marked the halfway point between the two nothing little towns—when she saw him. He was standing in the middle of the road, on the wavering yellow carpet of her headlights. His eyes reflected the light like a frightened animal, but he looked as real as any boy she’d ever seen. Even if he was dead.

She slammed on the brakes instinctively, and dust flew up around the Jeep and into the open windows. When it skidded to a stop, he was standing in front of the bumper, tiny particles of dirt floating in the air around him.

For a second, neither one of them moved. Edie was holding her breath, staring out beyond the headlights at the tall boy whose skin was too pale and eyes too blue.

“I’m okay, if you’re worried,” he called out, squinting into the light.

Edie clutched the vinyl steering wheel, her hands sweaty and hot. She knew she should back up—throw the car into reverse until he was out of sight—but even with her heart thudding in her ears, she couldn’t do it.

He half-smiled awkwardly, brushing the dirt off his jeans. He had the broad shoulders of a swimmer, and curly dark hair that was too long in places and too short in others, like he had cut it himself. “I’m not from around here.”

She already knew that.

He walked toward her dented red Jeep, tentatively. “You aren’t hurt, are you?”

It was a question no one ever asked her. In elementary school, Edie was the kid with the tangled blond braids. The one whose overalls were too big and too worn at the knees. Her parents never paid much attention to her. They were busy working double shifts at the refinery. Her brother was the one who wove her hair into those braids, tangled or not.

“I’m fine.” Edie shook her head, black bobbed hair swinging back and forth against her jaw.

He put his hand on the hood and bent down next to her open window. “Is there any way I could get a ride into town?”

Edie knew the right answer. Just like she knew she shouldn’t be driving on Red Run in the middle of the night. But she hadn’t cared about what was right, or anything at all, for a long time. A year and six days exactly—since the night her brother died. People had called it an accident, as if somehow that made it easier to live with. But everyone knew there were no accidents on Red Run.

That was the night Edie cut her hair with her mother’s craft scissors, the ones with the orange plastic handles. It was also the night she hung out with Wes and Trip behind the Gas & Go for the first time, drinking Easy Jesus and warm Bud Light until her brother’s death felt like a dream she would forget in the morning. The three of them had been in class together since kindergarten, but they didn’t run in the same crowd. When Wes and Trip weren’t smoking behind the school or hanging out in the cemetery, they were holed up in Wes’ garage, building weird junk they never let anyone see. Edie’s mom thought they were building pipe bombs.

But they were building something else.

The blue-eyed boy was still leaning into the window. “So can I get a ride?” He was watching her from under his long, straight lashes. They almost touched his cheeks when he blinked.

She leaned back into the sticky seat, trying to create some space between them. “What are you doing out here, anyway?”

Would he admit he was out here to kill her?

“My parents kicked me out, and I’m headed for Baton Rouge. I’ve got family down there.” He watched her, waiting for a reaction.

Was this part of the game?

“Get in,” she said, before she could change her mind.

The boy walked around the car and opened the door. The rusty hinges creaked, and it reminded Edie of the first time Wes opened the garage door and invited her inside.

The garage was humid and dark, palmetto bugs scurrying across the concrete floor for the corners. Two crooked pine tables were outfitted with vises and tools Edie didn’t recognize. Wire and scrap metal littered the floor, attached to homemade-looking machines that resembled leaky car batteries. There were other salvaged and tricked-out contraptions—dials that looked like speedometers, a portable sonar from a boat, and a long needle resting on a spool of paper that reminded her of those lie detectors you saw on television.

“What is all this stuff?”

Wes and Trip glanced at each other before Wes answered, “Promise you won’t tell anyone?”

Edie took another swig of Easy Jesus, the liquid burning its way down her throat. She liked the way it felt going down, knowing it would burn through her memories just as fast.

“Cross my heart and hope I die,” she slurred.

“It’s hope to die,” Trip said, kicking an empty beer can out of his way. “You said it wrong.”

Edie stared back at him, her dark eyes glassy. “No, I didn’t.” She tossed the empty bottle at a green plastic trash can in the corner, but she missed and it hit the concrete, shattering. “So are you gonna tell me what you’re doing with all this crap?”

Wes picked up a hunk of metal with long yellow wires dangling from the sides like the legs of a mechanical spider. “You won’t believe us.”

He was right. The only thing she believed in now was Easy Jesus. Remembering every day to forget. “Try me.”

Wes looked her straight in the eye, sober and serious. He flicked a switch on the machine and it whirred to life. “We’re hunting ghosts.”

Edie didn’t have time to think about hanging out with Wes and Trip in the garage. She needed to focus on the things they had taught her.

She was driving slower than usual, her hands glued to the wheel so the blue-eyed boy wouldn’t notice how badly they were shaking. “Where are you from?”

“You know, you really shouldn’t pick up strangers.” His voice was light and teasing, but Edie noticed he didn’t answer the question.

“You shouldn’t get in the car with strangers either,” she countered. “Especially not around here.”

He shifted his body toward her, his white ribbed tank sliding over his skin instead of sticking to it the way Edie’s clung to hers. The cracked leather seat didn’t make a sound. “What do you mean?”

She felt a wave of satisfaction. “You’ve never heard the stories about Red Run? You must live pretty far away.”

“What kind of stories?”

Edie stared out at the wall of trees closing in around them. It wasn’t an easy story to tell, especially if you were sitting a foot from the boy who died at the end of it. “About twenty years ago, someone died out here. He was about your age—”

“How do you know how old I am?” His voice was thick and sweet, all honey and molasses.

“Eighteen?”

He lifted an eyebrow. “Good guess. So what happened to him?”

Edie knew the story by heart. “It was graduation night. There was a party in Black Grove and everyone went, even Tommy Hansen. He was quiet and always kept to himself. My mom says he was good-looking, but none of the girls were interested in him because his family was dirt-poor. His dad ran off and his mother worked at the funeral home, dressing the bodies for viewings.”

Edie saw him cringe in the seat beside her, but she kept going. “Tommy worked at the gas station to help out and spent the rest of his time alone, playing a beat-up guitar. He wanted to be a songwriter, and was planning to leave for Nashville that weekend. If the party had been a few days later, he might have made it.”

And her brother would still be alive.

Edie remembered the night her brother died, his body stretched out in the middle of the road. She had stepped too close, and a pool of blood had gathered around the toes of her sneakers. She had stared down at the thick liquid, wondering why they called the road Red Run. The blood was as black as ink.

“Are you going to tell me how that kid Tommy died?” The boy was watching her from under those long eyelashes.

Edie’s heart started racing. “They had a keg in the woods, and everyone was wasted. Especially Katherine Day, the prettiest girl in school. People who remember say that Katherine drank her weight in cheap beer and wandered into the trees to puke. Tommy saw her stumbling around and followed her. This is the part where folks disagree; in one version of the story, Tommy sat with Katherine while she threw up all over her fancy white sundress. In the other version, Katherine forgot about how poor Tommy was—or noticed how good-looking he was—and kissed him. Either way, the end is the same.” Edie paused, measuring his reaction. At this point in the story, people were usually on pins and needles.

But the blue-eyed boy was staring back at her evenly from the passenger seat, as if he already knew the way it ended.

“Don’t you want to know what happened next?”

He smiled, but there was something wrong about it. His eyes were vacant and far away. Was he remembering? He sensed Edie watching him, and the faraway look was gone. “Yeah. How did he go from making out with the prettiest girl in school to getting killed?”

“I didn’t say he was killed.” Edie tried to hide the fear in her voice. She didn’t want him to know she was afraid.

“You said he died, right?”

She didn’t point out that dying and being killed weren’t the same thing. If Edie hadn’t known she was in over her head the minute he got in the car, she knew now. But it was too late. “Katherine was dating a guy on the wrestling team, or maybe it was the football team, I can’t remember. But he caught them together—kissing or talking or whatever they were doing— and dragged Tommy out of the woods with a bunch of his friends.”

The boy’s blue eyes were fixed on her now. “Then what happened?” His voice was so quiet she had trouble hearing him over the crickets calling out in the darkness.

“They beat him to death. Right here on Red Run. Some guy who lived out in the woods saw the whole thing.”

The boy nodded, staring out the window as the white bark of the pines blurred alongside the car. “So that’s why no one drives on this road at night?”

Edie laughed, but the sound was bitter and cold. About as far away from happy as it could be. “This is the Bayou. If you avoided every road where someone died, there wouldn’t be any roads left. Folks don’t drive on Red Run at night because Tommy Hansen’s ghost has killed six people about our age. They say he kills the boys because they remind him of the guys who beat him to death, and the girls because they remind him of Katherine.”

Edie pictured her brother lying in the glow of the police cruiser’s spotlight, bathed in red. She had knelt down in the sticky dirt, pressing her face against his chest. Will’s heart was beating, the rhythm uneven and faint.

“Edie?” She felt his chest rise as he whispered her name.

She cradled his face in her hands, but he was staring blankly beyond her. “I’m here, Will,” she choked. “What happened?”

Will strained to focus on Edie’s tear-stained face. “Don’t worry. I’m gonna be okay.” But his eyes told a different story.

“I should have listened . . .”

Will never finished. But she didn’t need to hear the rest.

Edie could feel the blue-eyed boy watching her. She bit the inside of her cheek to keep from crying. She had to hold it together a little while longer.

“You really believe a ghost is out here killing people?” He sounded disappointed. “You look smarter than that.”

Edie gripped the steering wheel tighter. He had no idea how smart. “I take it you don’t?”

He looked away. “Ghosts are apparitions. They can’t actually hurt anyone.”

“Sounds like you know a lot about ghosts.”

It was the same thing Edie said the second time she hung out with Wes and Trip in the filthy garage. Wes was adjusting some kind of gadget that looked like a giant calculator, with a meter and a needle where the display would normally have been. “We know enough.”

“Enough for what?” She imagined the two of them wandering around with their oversized calculators, searching for ghosts the way people troll the beach for loose change and jewelry with metal detectors.

“I told you, we hunt ghosts.” Wes tossed the device to Trip, who opened the back with a screwdriver and changed the batteries.

Edie settled into the cushions on the ratty plaid couch. “So you hang out in haunted houses and take pictures, like those guys on TV?”

Trip laughed. “Hardly. Those guys aren’t ghost hunters. They’re glorified photographers. We don’t stand around taking pictures.” Trip tossed the screwdriver onto the rotting workbench. “We send the ghosts back where they belong.”

Wes and Trip weren’t as stupid as Edie had assumed. In fact, if the two of them had ever bothered to enter the science fair, they would’ve won. They knew more about science, physics mainly—energy, electromagnetism, frequency, and matter— than any of the teachers at school. And they were practically engineers, capable of building almost anything with some wires and scrap metal. Wes explained that the human body was made up of electricity—electrical impulses that keep you alive. When a person died, those impulses changed form, resulting in ghosts.

Edie only understood about half of what he was saying. “How do you know? Maybe it just disappears.”

Trip shook his head. “Impossible. Energy can’t be destroyed. Physics 101. Those electrical impulses have to go somewhere.”

“So they change into ghosts, just like that?”

“I wouldn’t say ‘ just like that.’ I gave you the simplified version,” Trip said, attaching another wire to his tricked-out calculator.

“What is that thing?” she asked.

“This—” Trip held it up proudly, “is an EMF meter. It picks up electromagnetic fields and frequencies, movement we can’t detect. The kind created by ghosts.”

“That’s how we find them,” Wes said, taking a swig from an old can of Mountain Dew. “Then we kill them.”

Edie was still thinking about that day in the garage when she smelled something horrible coming from outside. It was suffocating—heavy and chemical, like burning plastic. She rolled up her window, even though the air inside the Jeep immediately became stifling.

“Don’t you want to let some air in?” the blue-eyed boy ventured.

“I’m more concerned about letting something out.”

He waited for Edie to explain, but she didn’t. “Can I ask you a question?”

“Shoot,” she said.

“If you believe there’s a ghost on this road, why are you driving out here all alone at night?”

Edie took a deep breath and spoke the words she had rehearsed in her mind since the moment he climbed into the car. “The ghost that haunts Red Run killed my brother, and I’m going to destroy it.”

Edie watched as the fear swept over him.

The realization.

“What are you talking about? How do you kill a ghost?”

He didn’t know.

Edie took her time answering. She had waited a long time for this. “Ghosts are made of energy like everything else. Scatter the energy, you destroy the ghost.”

“How do you plan to do that?”

Edie knocked on the black plastic paneling on her door. It was the same paneling that covered every inch of the Jeep’s interior. “Ghosts absorb the electrical impulses around them— from power lines, machines, cars—even people. I have these two friends who are pretty smart. They made this stuff. Some compounds conduct electricity.” She ran her palm over the paneling. “Others block it.”

“So you’re going to trap a ghost in the car with you and— what? Wait till it shorts out like a lightbulb?”

“It’s not that simple,” Edie said, without taking her eyes off the road. “Energy can’t be destroyed. You have to disperse it, sort of like blowing up a bomb. My friends know how to do it. I just have to keep the ghost contained until I get to their place. They’ll do the rest.”

Tommy glanced at the black paneling. “You’re crazy, you know that?” His arm wasn’t draped casually over the seat anymore, and his hands were balled up in his lap.

“Maybe,” she answered. “Maybe not.”

He reached for the handle to roll down his window, but it wouldn’t turn. “Your window’s—” He paused, working it out in his mind. “It isn’t broken, is it?”

Edie took her foot off the gas and let the car roll to a stop. “You didn’t really think I’d pick up a hitchhiker, on a deserted road in the middle of nowhere?” She turned toward the blue-eyed boy, a boy she knew was a ghost. “Did you, Tommy?”

His eyes widened at the sound of his name.

Edie’s heart felt like it was trying to punch its way out of her chest. There was no way to predict how Tommy’s ghost was going to react. Wes had warned her that ghosts could psychically attack the living by moving objects or causing hallucinations, even madness. His mom had walked off the second-story balcony of their house when Wes was in fourth grade. It was only a few weeks after she had started hearing strange noises and seeing shadows in the house. Wes’ father wanted to move, but his mom said she wasn’t going to be driven out of her house by swamp-water superstition. She didn’t believe in ghosts. Not until one killed her.

Now Edie was sitting only inches away from a ghost that had already murdered six people.

But he didn’t look murderous. There was something else lingering in his blue eyes. Panic. “You can’t stop here.”

“What?”

“There’s something I need to tell you, Edie. But you have to keep driving. It’s not safe.” He was turning around in his seat, scanning the woods through the windows.

Edie bit the inside of her cheek again. “What are you talking about?”

Before he had time to respond, the light outside flickered as a shadow cut through the path of the car’s headlights.

Edie jumped, jerking her eyes back toward the road.

There was a man a few yards away, waving his arms wildly. “Get outta the car now!”

“It’s too late,” Tommy whispered. “He’s already here.”

“Who?”

“The man who killed me.”

Edie didn’t have a chance to ask him to explain. The man in the road was still yelling as he moved closer to the car. “Hurry up! Before that blue-eyed devil skins you alive like the rest a them!”

Tommy’s ghost grabbed her arm, but she couldn’t feel his touch. “Don’t listen to him, Edie. He wants to hurt you, the same way he hurt me. And your brother.”

“What did you say?” The words tore at Edie’s throat like razor blades.

“I didn’t kill any of those kids that died out here. He did.” Tommy pointed at the man in the road. “I watch the road. I try to make sure no one stops near his cabin. I tried to warn all of them, but they wouldn’t listen.”

Edie remembered her brother’s last words.

I should have listened . . .

She had assumed he was referring to the stories—the constant warnings to stay off Red Run after dark. What if she was wrong? What if he had been talking about a different warning altogether?

“No.” Edie shook her head. “Those guys beat you to death—”

Tommy cut her off before she could finish. “They didn’t. That’s the story he told the police. And no one believed a bunch of drunk kids when they denied it.”

The voice outside was getting louder and more frantic. “Whatever that spirit’s telling you is a lie! He’s trying to keep you in there with him so he can kill you! Come on out, sweetheart.”

It was easier to see the man now that he was just a few feet away. He was about her dad’s age, but worse for the wear. His green John Deere cap was pulled low over his eyes, and he was wearing an old hunting jacket over his broad shoulders despite the heat.

He was shifting from side to side nervously, his eyes flitting back and forth between the woods and the car.

“He’s lying. I swear,” Tommy—it was becoming harder to remember that he was a ghost, not a regular boy—pleaded. “Why do you think I got in the car? I wanted to make sure you didn’t stop. He doesn’t like it when people get this close to his place. Especially teenagers.”

“You expect me to believe some old guy is killing people because they’re coming too close to his house?” Her voice was rising, a dangerous combination of fear and anger burning through her veins.

“He’s crazy, Edie. He cooks meth back there at night, and he’s convinced people can smell it. He’s always been paranoid, but after being cooped up in a tiny cabin with those fumes for years, it’s gotten worse.”

Edie remembered the nauseating stench of melted plastic. She never would have recognized it. Still. The man was pacing in front of the car, wringing his hands nervously. There was something off about him. But then again, he was facing off against a ghost.

Tommy was still talking. “That’s what he was doing the night I got lost in the woods, only back then it was something else. He’s been cooking up drugs in his cabin for years, supplying dealers in the city. I was looking for this girl who wandered off, and I got all turned around. I didn’t realize how far I’d walked. There was a cabin.” He paused, looking out at the man in the green cap. “Let’s just say, I knocked on the wrong door.”

The man stopped in the path of one of the headlights, a beam of light creating shadows across his face. “You can’t trust the dead. No matter what they say, sweetheart.”

Edie reached for the door handle.

Tommy—the boy-ghost—grabbed her other hand. For a second, Edie thought she felt the weight of his hand on hers. It was impossible, but it gave her goose bumps all the same. “He beat me to death, Edie. Then he dragged my body all the way back to the party, and left me in the middle of Red Run.”

Edie didn’t know who to believe. One of them was lying. And if she made the wrong choice, she was going to die tonight.

Tommy’s blue eyes were searching hers. “I would never hurt you, Edie. I swear.”

She thought about everything Wes and Trip had taught her, which boiled down to one thing: You can’t trust a ghost. She thought about her brother lying in the road. I should have listened. He could’ve been talking about the man in the green cap—the one begging her to get out of the car right now.

What was she thinking? She couldn’t trust a ghost.

Edie threw the door open before she could change her mind. The smell of burnt plastic flooded into the Jeep.

“Edie, no!” Tommy’s eyes were terrified, darting back and forth between Edie and the man in the road. In that moment, she knew he was telling the truth.

She reached for the door to pull it shut again as the man in the green cap rushed toward the driver’s side of the car. When he passed through the headlights, Edie saw him grab the buck knife from his waistband.

Edie tried to close the door, but it felt like she was wading through syrup. She wasn’t fast enough. But the man in the green cap was, his arm coming around the edge of the door. His knife was in his hand, reddish-brown lines streaking the dull blade.

“Oh, no you don’t, you little bitch!” The man grabbed the metal frame before she could close the door, the blade of the knife waving dangerously close to her face.

Tommy appeared just outside the open car door, only inches from the man wielding the knife. Before the man had a chance to react, Tommy rushed forward and stepped right through him.

Edie saw the man’s eyes go wide for a second, and he shivered.

“Back up!” Tommy shouted.

Edie didn’t think about anything but Tommy’s voice as she turned the key, grinding the ignition. She threw the car into reverse, slamming her foot on the gas.

The man swore, his hand uncurling from the handle of the knife. He tried to hold onto the doorframe, his filthy nails clawing at the metal.

Then his fingers slid away, and Edie saw him hit the ground.

She heard the scream as the Jeep bucked and the front tire rolled over his body. Edie didn’t stop until she could see him lying facedown in the dust. She could see the crushed bones, forced into awkward angles. He wasn’t moving.

Edie didn’t notice Tommy standing next to the car. He pulled the door open, bent metal scraping through the silence, and knelt down next to her. “Are you okay?”

“I think I killed him.” Her voice was shaking uncontrollably.

“Edie, look at me.” Tommy’s was calm. She leaned her head against the seat, turning her face toward his. “You didn’t have a choice. He was going to kill you.”

She knew Tommy was right. But it didn’t change the fact that she had just killed a man, even if that man was a monster.

Tommy’s blue eyes were searching her brown ones, their faces only inches apart. “What made you trust me?”

“Your eyes,” Edie answered. “The eyes don’t lie.”

“Even if you’re a ghost?”

Edie smiled weakly. “Especially if you’re a ghost.”

She looked out at the road. For the first time in forever, it was just a road—dirt and rocks and trees. She tried to imagine what it would be like to spend every night out here, so close to the place where you died.

“You’re the first person who ever believed me,” Tommy said. “The first person I saved.”

“Then why did you stay here for so long?”

Tommy looked away. “I didn’t have a choice.”

Edie remembered Wes telling her that most ghosts couldn’t leave a place where they had died traumatically. They were chained to that spot, trying to find a way to right the wrong.

When he turned back to face her, Edie noticed the sadness lingering in his eyes. And something else. . . .

Tommy was fading, flickering like static on an old TV set. He stared down at his hands, turning them slowly as if seeing them for the first time.

“I think you can move on now,” Edie said gently. “You know, to wherever you’re supposed to be. Red Run doesn’t need protecting anymore.”

“I don’t know where I’m supposed to be. But wherever it is, I’m not ready to go.” Tommy was still fading. “There are so many things I never had a chance to do.”

Edie ran her hand along the black paneling inside the Jeep, and looked at him. “Get in.”

Tommy hesitated for a second, smiling. “Just don’t take me to meet the friends who made that stuff.”

Edie smiled back at him. “You can trust me.”

As she drove away, Red Run disappearing into the darkness, Edie felt the weight of this place disappear along with it. “So where do you want to go?”

Tommy was still watching her.

The girl who wasn’t afraid to hunt a ghost.

“Maybe I’ll hang out with you for a while.” Tommy put his hand on top of hers, and she didn’t need to feel the weight of it to know it was there. “There are always things that need protecting.”