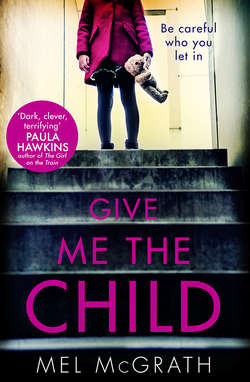

Читать книгу Give Me the Child: the most gripping psychological thriller of the year - Mel McGrath, Mel McGrath - Страница 11

CHAPTER FOUR

ОглавлениеI left the laundry bags in the hallway back home at Dunster Road and went into the kitchen where Freya and Tom were sitting at the table having breakfast.

‘Hi, Mum!’ Freya leaped up and clasped her arms excitedly around my waist. I dropped a kiss on her head.

‘Hey, sweet pea.’ My eyes cut to Tom but he was looking away. ‘Did Dad tell you, we’ve got a visitor?’ Before I’d left we had agreed that the best way to break the news was to tell the truth and be positive about it.

Freya nodded. Something passed across her face I couldn’t read. She gave me a cheesy, pleading look. ‘Can you stay home today, Mum? Pleeease.’

I’d been dreading this question, because I knew I wouldn’t be able to give her the answer she needed and deserved. Not with a new parent meeting at the clinic and the big grant application looming.

‘I’m really sorry, darling. Dad’ll be here and I’ll try to come home as early as I can, OK?’

I was already horribly late for work as it was. I thought about taking the car but I knew Tom would want to take the girls out somewhere and he needed it more than I did. In any case, it was rush hour and probably quicker to do what I usually did and run. Plus, I could use the thinking time. So I pulled on my gear and set off, one leg following the other in a two-step so familiar now it was automatic. I’d been running for over a decade, since a therapist had suggested taking regular exercise might help ward off another episode of mental illness. It was good for the brain, she said. I knew that, though I didn’t tell her so. Actually, I could have quoted her the studies: Dr Solomon Synder at Johns Hopkins, who discovered endorphins in the seventies; Henning Boecker at the University of Bonn, whose work on the opioid receptors defined the runner’s high. All the same, I took her advice. For years now I’d used my running time between home and work as a bridge between my two selves: Cat Lupo, mother, wife, sister and mild wino, with a penchant for trashy TV and popping candy, and Dr Caitlin Lupo, specialist in child personality disorders, clinician, ex-expert witness and all-out serious person.

As my legs found their rhythm, I wondered how Cat and Caitlin had become so disconnected from each other. Who was this creature, this mother, wife, psych, who looked like me and sounded like me, but who had never once in a dozen years suspected her husband of cheating, let alone of having another child? Had I somehow wilfully closed my eyes to Tom’s betrayal? Or was I just blind to his faults? I tried to think back to the late stages of my pregnancy and the stay in the psych ward. I had never apologised for my illness because I hadn’t thought mental illness was something anyone needed to apologise for. In any case, how could I have spotted that things had become so difficult for Tom when I was myself so radically altered? Or perhaps they hadn’t been as tricky as Tom was now making out. Maybe Tom simply made the most of an opportunity. And if he’d done that once, who was to say he hadn’t done it a dozen times? For all I knew he’d been cheating on me for the whole twelve years of our marriage.

At the top of Dunster Road, I stopped for a second and glanced back at the house which had, for so long, been my unquestioned home. The safe haven which I’d worked and fought for and sweated over. For some time now, we’d needed to cast a questioning eye over the fabric of our marriage and accept it had threadbare patches. We were too wedded to the idea of being the couple who didn’t ‘do’ state-of-the-nation discussions, of always being cooler than that. But what if our coolness was just dishonesty in disguise? What had only yesterday seemed like a marriage built of bricks and mortar now felt more like a tent, and a broken tent at that. I imagined Ruby Winter lying in the spare bed, an unwanted presence, like some sinister-shaped cell which might at any moment begin stealthily to consume the healthy cells around it. And then I felt bad for the thought, because what was Ruby, after all, but a little girl who had lost her mother?

I arrived at the entrance to the park. The sun was already hot, and I’d forgotten my water bottle. As I headed towards the drinking fountain by the bandstand, I wondered how two intelligent, articulate people could have failed so completely to ask the hard questions. At first it was all mad, carefree sex. Then came our high-octane period when we were so focused on our careers that nothing could distract us. After that was the period of trying to get pregnant. Once Freya was born we’d both been distracted, me fragile and with a new baby and Tom putting in the hours at Adrenalyze. Was that when things had changed? Or was it when the Rees Spelling ‘boy in the wood’ case blew open and the tabloids went after me? Or did it happen later, once Tom had quit Adrenalyze to work on Labyrinth and the success he so longed for hadn’t come overnight; when our finances had got tight, we’d had to give up the part-time childminder, and Tom had been sucked into becoming a househusband, a role he’d never wanted and often complained bitterly about? So many gathering clouds we’d chosen to ignore. Now the storm had finally arrived, would we be strong enough to weather it?

As I turned into the car park at the institute, I began to tell myself that somehow we were going to have to come back from this. If not for us, then for Freya. And that meant I was going to have to accept the new member of the family and find a way to learn to trust Tom again. Maybe not now, not today, not next week even, but soon. Because if I didn’t, or I couldn’t, the effects would ripple outwards to our daughter in ways none of us could predict. And we would all live to regret it.

I showered and changed into my usual work uniform – navy skirt with a white blouse – then swiped my card through the reader at the research block and went down the corridor to my office. Claire wasn’t at her desk, but she’d left a thermos of coffee for me. I sat down, poured the black oily brew into a mug, and woke up my screen. It was just after ten but the heat of the day was already distracting and I felt the lack of sleep, coupled with the events of the early morning, roll over me like some dense, tropical fog. As I turned to set the fan going, a tap came on the door and Claire’s face popped round.

‘Good, you’re here. Leak fixed?’

There was a momentary pause while I recalled the lie I’d told and formulated a response. ‘Thanks, yes, the emergency plumber came.’

Claire pulled up her hair and flapped her hand over the air current to cool her neck then stopped in her tracks. ‘Are you OK? You look a bit knackered.’

‘Just the heat.’ I wasn’t ready to talk about the arrival of Ruby Winter with Claire yet. Or with anyone.

‘Did you see on the news about those stabbings? Quite near you, weren’t they? One day the whole city’s just going to, like, implode.’ There had been a spate of gang-related knife crime over the summer. Yellow boards had appeared in unexpected places, along with mournful shrines to dead teens reconfigured as ‘warriors’ and ‘the fallen’.

I said I’d seen the news though, of course, I hadn’t.

‘Your rescheduled nine o’clock is here. I said ten fifteen, but she’s a bit early.’ Claire’s voice dropped to a whisper. ‘You may wish to adopt the brace position. I think you’re about to hit some bumpy air.’

I surprised myself by laughing. ‘Give me a few minutes to review the file, then show her in.’

I took a few breaths to clear my head of the events of the past few hours, and turned my attention to what lay ahead. As director of the clinic, it fell to me to deliver the news that in our view, Emma Barrons’ twelve-year-old son Joshua was a psychopath. Not that I would use that word. Here at the institute the official diagnosis was CU personality disorder. Callous and unemotional. Like that sounded any better.

Joshua Barrons had been referred to the clinic from an enlightened emergency shrink after he’d tried repeatedly to flush the family kitten down the toilet. A week before, a plumber had used an optical probe to locate a blockage in the drains at the Barrons’ family home. Joshua liked the probe and wanted to see it again and maybe even get a chance to use it. He thought that flushing the kitten would be a good way to do this, and when his nanny tried to stop him, he set fire to her handbag. According to the nanny, who we’d already met, Joshua’s behaviour, though extreme, was nothing new. His exasperated mother had taken to spending weeks at their country home, leaving Joshua in London so that she could avoid dealing with him. The boy’s father, Christopher Barrons, was rarely at home and when he was, there were fights. Once or twice, the nanny reported, she’d heard the sounds of scuffling and Emma had appeared with scratches and bruising, though, so far as she knew, the father had never hit his son. There were no other children. There was no kitten now either. The nanny had dropped it off at a shelter on her way to the doctor’s office. Hearing the story, the doctor had referred Joshua to a psychiatrist.

Over the years, Joshua had gone through many nannies and many diagnoses: ADHD, depression, defiance disorder… The list went on. He’d seen a psychologist and been prescribed, variously, methylphenidate, dexamfetamine, omega 3s and atomoxetine, been put on a low sugar, organic diet, and had psychotherapy. None of that had worked. The emergency shrink had done some initial tests and referred the boy to the clinic. In the report he was characterised as impulsive and immature with shallow affect, an impaired sense of empathy and a grandiose sense of himself. Left untreated, the psych thought the boy was a ticking time bomb.

Here at the clinic we specialised in kids like Joshua. During his initial assessment, we had run him through the usual preliminary tests – Hare’s psychopathy checklist and Jonason and Webster’s ‘Dirty Dozen’. Until I’d had a chance to assess him more thoroughly and run some scans I couldn’t be absolutely certain of a diagnosis, but there was little doubt in my mind. In my opinion, as well as that of the clinic’s therapeutic head, Anja De Whytte, Joshua Barrons was a manipulative, amoral, callous, impulsive and attention-seeking child whose neuropathy showed all the signs of conforming to the classic Dark Triad: narcissism, Machiavellianism and psychopathy. He wasn’t evil, but the way his brain worked could make him seem that way.

I was prepared for a tricky conversation. For the next hour or two I’d have to put thoughts of Tom and Ruby Winter out of my mind as much as I could and focus on my patient. Joshua Barrons and his family deserved that. It was my job to do whatever I could to help him. Plus, we needed him. There were children all over the country who displayed at least some of the traits of CU disorder but to find a kid whose personality was at the extreme edge was rare. Joshua had much to teach us. And we were keen to learn from him. His was exactly the kind of case most likely to win us the grant we needed to advance the clinic’s work on kids with personality disorders of all kinds.

Joshua’s mother was thin and brittle, with the anxious, hooded eyes of a starved cat. She took the seat I offered her, scoping out the featureless walls, the shelves stacked with neuroscience journals and research files.

I’d read about the Barrons family in the file. They were rich and local. Christopher Barrons had made a mint in the London property market in the eighties and nineties, buying up workers’ cottages like those around the Pemberton, installing laminate flooring and selling them on to middle-class professionals, using the profits to accumulate an enormous portfolio of ex-local authority flats which he rented out at exorbitant rates to twenty-somethings unable to get on the property ladder themselves. A few years ago he’d been knighted, though not, presumably, for buying up publically funded housing on the cheap and using it to subsidise his private empire, though these days, of course, anything was possible.

I introduced myself and went through a few preliminaries. Emma waited for me to finish. In an immaculately clipped voice, she said, ‘My husband refuses to believe there’s anything wrong with Joshua that one of the major public schools can’t fix. He thinks if we get Joshua into Eton, our son will stop flushing kittens down the lavatory.’

I’d run into the ‘my child’s too well bred to be a psycho’ argument before and knew it for what it was: embarrassment combined with a wafer-thin sense of superiority brought in as a defence against the situation in which a woman like Emma Barrons found herself. The Barrons were used to being able to buy themselves out of almost any situation. I didn’t judge them for that; what parent doesn’t do whatever it takes for their kids? But money wasn’t the point here and that was what left Emma and Christopher Barrons at a loss.

I leaned forward and steepled my hands to give myself more professional authority.

‘And what do you think?’

I felt her pull back. A pulse thumped in her throat at the suprasternal notch. She wasn’t here to have her opinion canvased. What she wanted was exactly what we couldn’t offer her: a cure. A tiny frown appeared on her otherwise waxy face. ‘I should have thought that was rather obvious. I’m here, aren’t I?’

‘You are, and I’m very glad about that, because we’re going to help your son.’

The tiny frown returned. ‘Forgive my scepticism, Dr Lupo, but Joshua has been diagnosed any number of times by a series of private psychiatrists and prescribed dozens of pills with names I can’t pronounce, but he’s still trying to flush kittens down toilets. I’m here because I’m afraid for my child and I don’t know what else to do and because the emergency psychiatrist who looked at Joshua hinted that he would section him if I didn’t agree to come.’

I sat back and settled in for the long haul. Emma Barrons had a point. Diagnosis of paediatric mental disorders was both complex and highly controversial. Cases of child psychopathy were missed or misdiagnosed all the time, in part because it was relatively rare and in part because psychiatrists were resistant to giving kids such a devastating label. Even the most experienced psychiatrists and neurologists often got it wrong, either because they couldn’t see it or because they didn’t want to.

As I began what I hoped was a reassuring speech about how different our approach was at the clinic, I found my mind once more wandering back to the situation at home. A bubble of anxiety burst at the back of my throat. By now Freya would have met her half-sister. What if they didn’t get on? What if Freya blamed her father and turned against him? Against both of us? So many what ifs. Hurriedly, I put those thoughts back into the box labelled ‘home life’ and returned my attention to my patient’s mother. My upbringing had made me good at compartmentalising. It was something Tom liked about me. The hallmark of survivors. He thought of himself as one too. ‘You and me both have a ruthless streak,’ he’d said to me once in the early days. At the time, I let it go. I let a lot of things go back then.

Emma Barrons waited for me to finish and said, ‘I sometimes wonder if Joshua behaves this way because he hates me. On the rare occasions Christopher comes home, Joshua runs into his arms. Runs. And then it’s all “Daddy this” and “Daddy that”. That’s why my husband can’t see it. He thinks I haven’t put in enough effort to find the right school for our son. He won’t accept that Joshua is too disruptive to go to a normal school.’

I mentioned we could arrange to have Joshua home-schooled by a specialist tutor, at least while he was still in treatment. As I was speaking, Emma Barrons began twirling the index finger of her right hand around the left. She wasn’t listening. I couldn’t blame her. By the time the kids in our clinic had been referred to us, their parents had usually gone through years of anguish. Most often they were on the brink. Taking an e-cigarette from her ostrich bag and holding it briefly in mid-air, she said, ‘Do you mind?’ and, without waiting for an answer, drew the metal tube to her lips and sucked like an orphaned lamb at the teat.

‘I suppose there’s no point in asking how Joshua got this way?’ she said.

‘We don’t know exactly. The only thing we’re sure of is that there are certain genetic and neurological markers often associated with children with the disorder. Joshua has the low MAO-A variant gene. It’s an epigenetic problem, an issue with the way a particular gene expresses itself, which can affect the production of serotonin in the brain and lead to flattened emotional responses and a tendency towards problems with impulse control. You might have noticed that Joshua doesn’t have the same fear response as most other children. He may need to go to extremes in order to feel pleasurable emotions. In fact, to feel anything at all. But I can explain it in more detail to you as we go along.’

Emma paused just long enough for her nicotine fix then launched into a diatribe about her son’s reckless behaviour. I checked the clock. I loved my work and I was motivated by a strong sense that we could help kids like Joshua, kids who we in the brain business call ‘unsuccessful psychopaths’ because they are unable to disguise their dangerousness, but knew from experience that it would be a slow and painful process, one which could derail at any time. I steered the conversation towards more productive territory and spent a few minutes outlining what the institute proposed for the boy’s therapy programme. Most of our kids were in residential care but, since the Barrons lived nearby, I thought it might be better for Joshua if we tried him out as a day patient. We would spend the first few weeks attempting to unlock Joshua’s deep motivators, the things that really drove him, and then use them to try to modify his behaviour. Eventually we hoped to alter the neural pathways in his still malleable brain.

‘I do really want to emphasise that there is hope,’ I said.

Emma Barrons shot me a baleful look. We finished up and Emma Barrons stood to go. At the door, she turned and, with an odd, damaged smile on her face, she said, ‘I didn’t really want a child, you know, but Christopher had an heir thing going on. I suppose Joshua is the price I paid for marrying money. Quite a high price, as it turned out.’

For a moment she just stood there in the doorway working the rings on her hands. ‘I suppose that shocks you, Dr Lupo?’

‘Call me Caitlin. We’re going to get to know one another quite well.’

‘Caitlin, then.’ One side of her mouth rose up in a half-smile. ‘Do I shock you?’

‘Right now, Emma, absolutely nothing would shock me.’