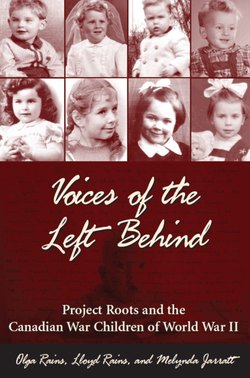

Читать книгу Voices of the Left Behind - Melynda Jarratt - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter 1

The Canadians in Britain, 1939–1946

by Melynda Jarratt

“They’re oversexed, overpaid, and over here!”

King George inspects Canadian troops at the army base in Croydon, England, during World War II, date unknown. The Canadians spent more time in England than any of the other Allied troops. Of 48,000 war brides, 44,000 were from Britain, the majority of whom came to Canada after the war and settled here. But the Canadians also left behind an estimated 23,000 war children from relationships they had with single and married women in the U.K.

“They’re oversexed, overpaid, and over here!” Well-known comedian Tommy Trinder touched a nerve in British society when he uttered those famous words during World War II.1 Intended to be a gibe at American GIs who were romancing British women, the saying could easily apply to the Canadians, whose stay in Britain exceeded the GIs’ by more than two years.

Between 1939 and 1945, nearly half a million Canadian soldiers poured into Great Britain. Most of them were concentrated in southern England, and some who arrived in Aldershot in 1939 spent up to six years in the area. Naturally, the Canadians met British women, and whenever that happened there was romance and its inevitable results.

Forty-four thousand Canadian servicemen married British women during the war,2 but a large number also had relationships with local women — some brief affairs, others long term — which resulted in the birth of an estimated 23,0003 illegitimate4 children whom we know as the British war children of World War II.

A homecoming party for a soldier back from Europe, at the Club Venetian, Montreal, December, 1945. When the Canadians came home, girlfriends left behind were easily forgotten.

Although the terms “illegitimate” and “bastard” no longer apply today, they were once powerful social statements on the position of unwed mothers and what their fatherless children could expect in British society. Marginalized and disenfranchised by virtue of their marital and birth status, both mothers and war children were treated with derision and received little, if any, sympathy or support from either side, British or Canadian. (See Chapter 8 for further discussion of this issue.)

Unlike the war brides who married their Canadian boyfriends and came to Canada to live at the end of the war, these women were abandoned by their soldier boyfriends, now officially Canadian veterans, who disappeared off the face of the earth once they returned to Canada at the end of the war. Desperate pleas to the Canadian military authorities, Veterans Affairs and External Affairs as to the whereabouts of missing fathers were fruitless — and continue to be to this day under the pretext of Canada’s Privacy Act.

Left alone to raise their children in a highly judgmental, moralistic society, often without financial support or skills, many women decided to give up their children for adoption or were forced to hand them over to relatives. And at a time when there were few social supports or economic opportunities for women, those who decided to go it on their own suffered enormous social consequences that still reverberate in the lives of the war children today.

John Costello, in his famous study of changing social values during World War II titled Love, Sex and War, describes these British women and the wartime circumstances that found them unwed and pregnant with the children of foreign soldiers:

Of the 5.3 million British infants delivered between 1939 and 1945, over a third were illegitimate — and this wartime phenomenon was not confined to any one section of society. The babies that were born out of wedlock belonged to every age group of mother, concluded one social researcher.

Some were adolescent girls who had drifted away from homes which offered neither guidance nor warmth and security. Still others were women with husbands on war service, who had been unable to bear the loneliness of separation. There were decent and serious, superficial and flighty, irresponsible and incorrigible girls among them. There were some who had formed serious attachments and hoped to marry. There were others who had a single lapse, often under the influence of drink. There were, too, the “good-time girls” who thrived on the presence of well-paid servicemen from overseas, and semi-prostitutes with little moral restraint. But for the war many of these girls, whatever their type, would never have had illegitimate children.5

One of the most famous war children is legendary blues guitarist Eric Clapton, who discovered in March 1998, that his father, Edward Fryer, was a soldier from Montreal. Raised by his grandparents as their son, Clapton found out when he was nine that his sister Patricia was actually his mother. His story of a lifelong search for a Canadian father he never knew is one that echoes loudly for the British war children of World War II.

NOTES

1 Trinder is widely credited for the famous saying “They’re overpaid, oversexed, and over here!”, intended as a gibe against American servicemen in Europe.

2 Immigration Branch, Annual Report of the Department of Mines and Resources 1947–48 (Ottawa: Edmund Cloutier, King’s Printer, 1948), p. 240. As cited in Melynda Jarratt, The War Brides of New Brunswick, master’s report (Fredericton: University of New Brunswick, 1995), p. 5.

3 This is a an estimate of Canadian war children born in Britain. Recent correspondence (December 2003) with the Public Records Office, the National Archives and the Office of National Statistics in the U.K. confirm that evidence of Canadian paternity found in the birth certificates for illegitimate children born during the war years has never been compiled and is therefore unavailable at this time. It has also been suggested that the number of children whose fathers were Canadian servicemen may never be known; married women whose British husbands were away during the war would have given their Canadian children their husband’s name, as opposed to the biological father’s name. We know this to be the case for several children whose stories appear in this book. The lack of readily available statistical evidence points to a need for further research in the British archives to determine through objective analysis the numbers of war children whose fathers were Canadian servicemen.

4 We used the word “illegitimate” only to separate children born out of wedlock from those whose parents were legally married. It by no means carries the social stigma it did as recently as ten years ago.

5 John Costello, Love Sex and War: Changing Values 1939-45 (London: Collins, 1985), pp. 276–77.

Exceeded All My Hopes

by John*

I was born at the end of 1946 in London, England, to an English mother and a Canadian soldier who had returned to Canada with his regiment in the middle of 1946. The months leading up to and immediately after my birth were very difficult for my mother. She was sent to a Roman Catholic home for unmarried mothers. After I was born, a charitable organization arranged for her to work as home help with a Roman Catholic couple in Sussex.

In 1947, my grandfather returned from naval service and set up home near Portsmouth in Hampshire, so I went to live with my grandparents. My mother, meanwhile, had managed to get office work in Sussex, and came to see us on the weekends. My grandfather’s home was a small holding in the countryside, and I have fond memories of this early period in my life. I also established a strong bond with my grandfather.

My mother met and married my stepfather in 1948. He was serving with the Royal Air Force, and I continued to live with my grandparents until he was posted to Nairobi in East Africa in 1949. I went abroad with my mother, and then was formally adopted by my stepfather when we returned to England in 1953.

I had a happy childhood, and my mother ensured that I acquired a good education. At age twenty-six I married and settled in Lincolnshire, where we have lived ever since. We have had two children of our own, who gave my mother much joy up to her death in 1992. My stepfather followed her shortly after in 1994.

All in all I have been fortunate and had a good life with no regrets, but I have always wondered about my Canadian father. With both my parents gone, in 1995 I decided to find out more about my biological father’s background. I had little information to go on: a name, the fact that he had been a Canadian soldier, and that he had been awarded a medal for bravery.

I began my research in the London archives and also made contact with Olga Rains at Project Roots. Olga was immensely supportive, and encouraged me with advice although, at that time, I had no real facts on which to base a search. Eventually I was able to link the name and the medal, and to acquire a copy of the military citation. Being a wartime citation, it did not, of course, contain any personal information, but it did provide me with a regiment and service number.

This was the breakthrough that Olga needed, and with her extensive contacts in Canada she was able to trace my father in a very short time. At the end of 1999 she telephoned my father on my behalf, and so initiated a relationship for which I am eternally in her debt.

For two years we corresponded and spoke on the telephone, getting to know each other and coming to terms with an almost miraculous reunion.

At the end of 2001 I retired from a working life of travel abroad, and in the summer of 2002 my wife and I visited Canada to meet my father. I do not possess the literary skills to describe how much it meant to both of us. Suffice it to say it was a memorable trip. We visited the places of my father’s childhood, and he provided me with a wealth of background information on my roots.

I can say that the whole experience has exceeded by far any hopes that I might have had when I embarked on my search, and I cannot thank Olga and everybody at Project Roots enough.

*John is a pseudonym

Still He Eludes Me

by Sheila Blake

My name is Sheila Blake (née Shoulders). I was born in England on March 3, 1944, in the small village of Shottermill, near Haslemere, Surrey, in a beautiful house called Ridgecomb.

I was thirty-seven years old when I first heard that my father was a Canadian. Although it was a shock, in retrospect I was not the least surprised.

My mother’s name was Eileen Patricia Ayling. During the war, she lived at Park Road as well as Worthing and Dolphin Road, Shoreham-by-Sea, Sussex, where I was raised.

I believe my Canadian father, Gavin McGuire or McGurk (spelling?), may have been based in Surrey, probably Hindhead. His uniform indicates he was an engineer and served with the Royal Canadian Engineers; however, he was also known as Gunner McGurk, possibly because he was initially with the Royal Canadian Edmonton Regiment (Artillery).

Sheila Blake’s father, Gavin McGuire or McGurk, may have been an engineer with the Royal Canadian Engineers. He joined up in Edmonton, Alberta.

He was six feet tall, red-headed and very well built. His eyes were blue. Not surprisingly, my son has red hair and a lazy eye, just like my father and myself. I know what he looks like, but am uncertain of his name. An elderly family member told me my father was Gavin McGuire or McGurk and that he came from Edmonton, Alberta.

Apparently, my father was badly injured during the D-Day landings and was shipped back to Saskatchewan. His mother wrote to my family with news of his condition, as she was concerned he would not recover from a severe head injury.

I’ve been told he survived the war and returned to the U.K. to be reunited with my mother and me. However, my mother had already married Frank Shoulders and was pregnant with my brother, so she stayed with her husband.

The portrait of my natural father came into my possession in November 1999, while I was visiting my family in Sussex, England.

My mother passed away in 1985, and before she died I believe she tried to tell me something about my father. However, she was so heavily sedated with morphine that she was unable to bring the memories back.

When I finally saw my father’s portrait fourteen years later, it dawned on me what she had been trying to say on her deathbed. I’ve just become a grandmother, and my grandson is the image of the man in the photo.

I do hope someone will recognize my father’s picture. I have a file that is now a good four inches thick, but am no nearer to discovering his whereabouts. It seems unbelievable that I can have a photo clearly showing his uniform and regimental badge, a probable name, a U.K. location during the war, and yet still he eludes me.

Sheila and her mother, Patricia Ayling. Sheila’s father was injured in the D-Day landings and was shipped back to Saskatchewan. In his absence, Patricia married another man in England.

Better Off without Him

by Alan Franklin

The ironic thing about my Canadian father is that sixty years ago he was stationed in the area where I now edit the local newspaper, writing stories about Canadian fathers who abandoned their British offspring sixty years ago.

I was born on February 11, 1946, exactly nine months after Victory in Europe Day, May 8, 1945. I was a victory celebration baby, born into austere postwar Britain, where cold houses, rationing and shortages of everything were our way of life.

Meanwhile, back in Canada with his English wife, my father Patrick Johnson (not his real name) was setting out on a successful career which ended, I am told, with him working as head foreman of the Vancouver water company. He had four children, two boys and two girls, one of them born around the same time as me.

Alan Franklin is the editor of the Surrey-Hants Star in Aldershot, England. His Canadian father has refused contact.

My mother had married another Canadian soldier, Corporal Franklin of the Paratroop Regiment, who also swiftly followed the pattern of the abandonment of British wives and girlfriends at the war’s end. So we were left to manage as best we could, my mother working at the post office telegrams department, doing administration for the Surrey Police and other office jobs to support us both. Meanwhile my grandmother kept house and cooked meals for my mother and me, my grandfather (a steam-engine driver) and my aunt (a civil servant).

Single parenthood was not fashionable then, and I knew no other boy without a father present. Sometimes I wondered who and where he was, but questions were discouraged and I just got on with my life until, in my teens, as a young reporter, I interviewed a private detective. This man traced missing relatives. I asked him to trace Corporal Reginald Franklin, not knowing then that he was not my real father. He did, with a “last trace” of him detected through a contact with the Canadian Legion.

When I revealed my research to my mother she was horrified; Franklin was even more of a dead loss than Johnson, whose last communication with my mother, some months before I was born, was a card posted from Canada in 1945 “wishing you well next year” — at my birth. This was the full extent of Johnson’s help to his secret English family.

My attempt at tracing Franklin flushed out the hitherto-unsuspected existence of Johnson. My mother was a little hazy about where he had come from and, Canada being a large country, I presumed I had no hope of finding him, so I forgot all about it until 1984, when I had just been appointed to my present job as editor of the Surrey and Hants Star in Aldershot, Hampshire, England.

Stories of the Canadian war children appear frequently in the Surrey-Hants Star.

My colleague John Walton, an experienced journalist and formerly the deputy editor of Soldier Magazine, also based in Aldershot, said he was off on a trip to Canada and would look up Johnson in the phone book. As he was headed for Vancouver he immediately discovered P. Johnson — there was just one in the phone book — and returned with his address. I then wrote a simple letter to my father, asking him to get in touch. He never did, although he subsequently claimed that a letter had been sent to me and that he even tried to visit me at my home in Alton, Hampshire.

This seemed unlikely, as I have never been hard to trace, being a well-known local journalist all my adult life, with my byline and picture appearing in papers going through tens of thousands of doors. Additionally, when I was a reporter I called every day at all the local police stations, so I was not exactly unknown to them! Neither did a letter come back marked “address unknown,” so my letter was certainly delivered.

Having deduced that my father didn’t want to know me, I again got on with my life, enjoying my family and career. Then, in 1998, Mark Maclay wrote a book called Aldershot’s Canadians, which told the stories of the 330,000 Canadian servicemen stationed in the Aldershot area during the war years. I reviewed it and sent a copy to Lloyd and Olga Rains, whom I knew as the couple who discovered fathers of war babies.

This was now the computer age and everybody, more or less, was easily traceable. It took Olga just a few minutes on her computer to come up with the address of several Johnsons, one of them my cousin Linda who, in turn, led me to my dad.

Linda and another cousin, Jeff, were friendly and helpful. I sent Linda pictures showing the family likeness, which I think is obvious, and saying that if there was any doubt I would happily arrange a DNA test, which I subsequently tried to do. But I hadn’t reckoned on the cold refusal of my father to show any interest in me, or agree to anything which a court didn’t order.

To say he didn’t want to know was an understatement: Linda told me he was a Shriner (a branch of Freemasonry) and a member of the Lutheran Church, and it was obvious that the last thing he wanted was me rattling a few skeletons round his doorstep. I thanked Linda for not doubting me and explained all the reasons why I was telling the truth. If I had wanted a “Canadian family” or to live in Canada, I already had my birth certificate stating that I was the son of a Canadian serviceman — my mother’s husband Franklin. So I could get a Canadian passport at any time. Because I am married to an American I could also get U.S. residency and, eventually, citizenship, so I was not motivated by a desire to move to Canada.

As for money, my wife and I presumed that if we ever traced my father he would probably be a bum on the streets. What other kind of man would abandon an unborn child and never inquire as to his welfare? In our view, he would need our help, not the other way around, and our help would have been gladly given.

I had two phone conversations with Patrick Johnson at that time, both of which were a trifle odd. He claimed to have flown to Britain with his wife in 1984 or 1985 and spent some time looking for me, even asking the police my whereabouts. We moved from the home in Alton, from which I had written the letter, in 1985, but we sold the house to close friends who could have located me in two minutes. I also told him in my letter that I edited the local paper, so finding me would not have taxed Sherlock Holmes. Mr. Johnson also claimed his wife has written me a letter, but I didn’t receive it. Very odd.

In his first phone call he said coldly, “I am not your father” — which begs the question of why he would claim to have tried to find me. After his first phone call, I dashed over to Guildford to talk to my mother and she was contemptuous of his denials.

I called him back and he said something that struck me as curious: “I can’t change my story now.” He admitted he had “been intimate” with my mother, but claimed it was only before his wedding in December 1943. My mother disputes this and says that in 1944, when both she and Patrick operated different switchboards in the Farnborough area, Patrick chatted to her and asked her over to the Canadian hospital to meet him. This led to their affair, which lasted some time. She was then posted away, and they resumed their relationship in 1945. She says he was aware she was pregnant and sent her the postcard wishing her luck.

Patrick claimed to know the name of my “real father” but wouldn’t reveal it. How this ties in with his claim that he didn’t see my mother after his marriage, I don’t know . . . I think that Patrick is ashamed of “playing around” shortly after his wedding. Had my conception happened first, perhaps he would have admitted it. However, the dates make him look bad, and he is ashamed to admit fathering me.

He promised to see me when he next came to England, in the summer of 1999, but I felt this was too long to wait. Foolishly, in 1998 I wrote a long and detailed letter to Johnson about my life, hoping this would interest him in my family. Instead, he has subsequently used it to make unpleasant points about me.

I last spoke to Patrick Johnson on September 3, 1999, when the phone rang at home at 9:30 p.m. He had been on his annual summer trip to the Isle of Wight, an island off the coast of Britain, where his first wife came from. He stays there with his late wife’s sister, who, I understand, lives in a house bought by Johnson.

He was calling from Liphook, a village in Hampshire around thirty miles from where we live in Fleet. But even though I could have been there in under an hour, he refused to allow me to come and meet him. This was the only time I felt really upset at his attitude: I knew this would be my only chance to see him, because of his advancing years and because he had already warned me not to call on him in Canada.

Had I known where he was calling from, I would have driven there anyway, but he was careful not to reveal this, although he said he was staying with relatives of his first wife. Mr. Johnson told me he was getting a lift to the airport in the morning to fly home to Canada. I begged him to see me, but he hadn’t the guts to do so, despite having promised that he would — a promise he had used simply to buy some more time.

He was very cold, guarded and kept trying to ring off. He did say he was making a tape about his wartime affair with my mother, which he would send me and also make available to his children on his death. He said he had consulted a solicitor on the Isle of Wight, and he expected a response from me once I had heard the tape. His prime interest seemed to be in limiting any possible damage to his precious reputation.

A Canadian soldier arrives in Canada after five long years overseas. Who knows if he left a child behind?

When I got the tape I decided I would make no further effort to contact Johnson. It contained a ridiculous, one-sided attempt at smearing my mother — the only person who kept me out of an orphanage — and was full of self-justification and excuses. It is one of the most disgusting statements I have ever heard, an opinion shared by the Rains, who could scarcely believe their ears. It seems, you see, that this strapping Canadian soldier was entirely overpowered and seduced by this little seven-stone, five-foot Englishwoman. What a terrible experience it must have been for him. I am surprised he didn’t seek immediate counselling.

So much for Johnson. The good news was that cousin Linda came over with her new husband, Bart, and spent her honeymoon with us in Hampshire in 2004!

Linda and Bart are a wonderful, outgoing Canadian couple and we spent some happy days seeing the sights and showing them England, where Linda’s father and uncles had spent their wartime years.

Our children, Daniel and Anne, at last had some relatives to relate to on my father’s side, where previously there had been a void. We have kept in touch since their return to Canada and we have a standing invitation to visit them.

Linda also brought loads of family history and pictures with her: at last my German/Canadian roots were revealed!

I phoned my half-brother Dale, in Ottawa, but he showed no interest, so at the time of writing Linda and Bart are our Canadian family. We are delighted to know them, and even if we never meet any other “Johnsons,” we will have succeeded in expanding our family in a wonderful way.

Awkward Moments

by Celestine

At the end of March 1989, I flew to Toronto to meet my Canadian father, Louis, for the first time. During the whole flight I was so nervous and the same thoughts kept racing through my mind. Did I look like him? I was not as good-looking as my English mother, Libby. She had beautiful long, curly, blonde hair and dark-brown eyes. I was just a plain dark blonde with straight hair cut in a bob.

I had seen a photo of Louis in the service, a handsome young soldier, but he never did send me a photo of how he looked now. So I tried to draw a picture in my mind: maybe his hair was all grey or white, or maybe he had no hair at all? Were his eyes like mine — not blue and not green, sort of in between?

It was not his fault that he couldn’t raise me: it was Libby’s. She left my father when she became pregnant. Libby didn’t love him the way he loved her. She was so young, only seventeen years old. My grandparents raised me, so I grew up thinking they were my parents and Libby was my sister.

I found out much later that Louis wanted to marry Libby, but my grandparents were against it. Besides, she didn’t really care about Louis. Libby liked to have fun, go out, and be carefree, and she did until she was in a bad accident that left her disabled.

As I walked through the doors at the airport and saw all the people who were waiting to welcome their families and friends, I wondered how I would find my father. As I stood there, a well-dressed man came towards me with a big bouquet of roses. It was Louis, my father. He put his arms around me and held me tight. The tears kept streaming down my face. We were both very emotional as we walked down the parking lot to where his car was.

This first visit with my Canadian father was a strange and emotional time. At first he wanted to see me as his “girlfriend” — and, more importantly, wanted other people to believe that this was so. Apart from his ego, he had great difficulty explaining me to friends, and there were quite a few awkward moments.

I could appreciate his discomfort, but I had spent the whole of my childhood in situations where no one wanted to say who I was, and there was no way I was going to put up with that at the age of forty-five.

So, initially, we had conflicts over his feelings towards me, what he wanted from me, and what I felt I could give. But we got along so well and I knew that he loved me and was proud of me.

When he became ill, I nursed him and worried over him. I stayed for a few days with my husband’s relations in Montreal, and this gave me the opportunity to talk to someone from outside the situation. I realized that Louis was terrified of losing me, the way he had lost my mother, his first and only love. This made him demanding and sometimes very difficult. I realized how much I missed him, and when I returned I was more confident and able to laugh at his “grumpy” ways.

I returned to Toronto for three weeks in May and we had a lovely time together. In July, my father came to us — something he had said he would never do. He stayed for ten weeks. He became a part of my family and I was really happy. He was spoiled and did not want to return to Canada.

I had not been prepared for how desolate I felt when he left, and I realized how important it is that we make the most of the time left to us. We made enquiries about him living with us, and it appears that he is not eligible, so we have to fight. He very much wants to come and stay with us. He is a very lonely man; he never married and has no family anymore.

Many young soldiers wanted a relationship with the mothers of their children but it was not meant to be.

I realize now that my father and I have a more intense relationship than most people under normal circumstances, but as long as he is happy and my husband, children and I are happy, then it doesn’t really matter what the rest of the world thinks.

Sometimes I think I am dreaming. That I could have found a father who loves me, hugs me and laughs and cries with me is more than I had ever hoped for.

His Father’s Eyes

by Melynda Jarratt

The most famous Canadian war child is legendary blues-rock guitarist Eric Clapton, whose father was a soldier from Montreal named Edward Fryer.

Clapton was born on March 30, 1945, to Patricia Molly Clapton, a sixteen-year-old English teenager whose brief relationship with the piano-playing soldier from Quebec resulted in pregnancy.

Raised by his grandparents, Eric was nine years old when he found out that his sister Patricia was actually his mother, but all he ever knew about his father was the name Edward Fryer and some rumours that he was involved in banking. He wasn’t even sure of the spelling: was it Fryer or Friar?

Project Roots first became involved in the search for Eric Clapton’s father in September 1997, when Lloyd and Olga Rains were contacted by an English lawyer who asked for information on the Canadian soldier Edward Fryer or Friar. The lawyer would not reveal his client’s name, only that he wanted information on Fryer.

The Rains had never heard of Eric Clapton, so the name Fryer meant nothing to them. They conducted a regular search and sent off the information to the lawyers. Little did they know that at the same they were looking for Canadian veteran Edward Fryer, so too was Michael Woloschuk, a writer for the Ottawa Citizen whose parallel search superseded Project Roots and ended up on the front pages of every major newspaper in the world in March 1998.

In an article in the Citizen on March 26, 1998, Woloschuk explained that he began looking for Edward Fryer in the fall of 1997, urged on by a friend who knew Clapton was planning a North American tour in March to promote his latest album, Pilgrim. Clapton was Woloschuk’s musical hero and, like anybody else who had read the musician’s 1985 biography, he knew that Clapton’s father was a Canadian soldier named Edward Fryer. He knew, too, that Clapton had never been able to find the man.

With the death in 1991 of Clapton’s five-year-old son, Conor, and the success of Pilgrim’s hit single, the sad but hopeful “My Father’s Eyes,” it seemed the right time for Woloschuk to use his journalistic connections to find Edward Fryer. He was right.

Six months later, on the eve of Clapton’s North American tour, the front-page article in the Citizen told the world about Eric Clapton’s father, a talented musician and artist who died of leukemia in a Toronto veteran’s hospital in 1985. Fryer was also a marrying man who left behind a trail of wives and children across Canada and the United States. Three half-brothers and sisters, from British Columbia to Florida, were thrilled to find out about their connection with Eric Clapton.

The story spread rapidly across North America, Britain and Europe. In an interview with the Toronto Sun the next day, Clapton was quoted as being pleased, if not a little irritated, that the family he had sought for so long was discovered by a Canadian newspaper reporter.

“First of all, I was furious that I have to find this stuff out through a newspaper. I think it was very intrusive — but then, newspapers are,” Clapton told the Sun. “Then I thought, this is great. The upside, the positive, is that it supplied me with information I’d never had before.”

According to the article, Fryer was cremated and his ashes were scattered off Florida waters by his last love, Sylvia (Goldie) Nickason, an Ontario woman with whom Fryer spent his last years.

The Rains’ involvement in the search for Edward Fryer had begun inauspiciously enough six months earlier, when they received their first correspondence from the English law firm. As she had done for so many others, Olga wrote back to the lawyer and said they would do a search, and she eventually sent along a list of sixteen addresses for E. Fryer or E. Friar. As is the case with so many other requests from lawyers, once the law firm got the information, Olga never heard from them again — not even to thank her for the list of names.

“It’s typical,” Olga says. “As soon as they get what they want, we never hear from them again, but we get used to it. It’s discouraging sometimes, but you don’t let it bother you. There are too many good people out there who appreciate what we do, and besides, we can always hope that the information we provided helped the war child find his father, and that would mean something good came out of our work even if we never find out about it.”

Months passed, and Olga never gave the request another thought. Other cases came up and she put the letters aside with the intention of recycling them, but somehow the correspondence survived.

In the meantime, unbeknownst to the Rains or to Clapton’s lawyers, Woloschuk was making headway with his own search. Olga says she will “never forget the day” they got the call from Canada saying that there was a big article in the Ottawa Citizen about this famous musician named Eric Clapton and his Canadian father, a veteran named Edward Fryer.

“I knew about Fryer, as we had done the search six months previously, but I said, ‘So who is this Eric Clapton?’ We’re old people; we don’t know anything about rock ’n’ roll music!”

Once they got over the surprise of learning the identity of the anonymous figure to whose lawyer they had provided a list of names and addresses, the Rains wrote the law firm, informing them that, with the Citizen article, the cat was now out of the bag. The Rains said they knew the anonymous client was Eric Clapton, and although they were very happy for him, they had never received as much as a thank-you for their efforts.

Less than a week later, a letter arrived at their doorstep, with a donation to Project Roots and a special thank-you from the lawyer: “I would like personally, and on behalf of our Client, to thank you for your assistance.”

After so many twists and turns, it was a fitting end to the search for a Canadian soldier whose son just happens to be one of the most famous musicians in the world today.

Mixed Blessings

by Olga Rains

Christine Wilson’s father was a Canadian serviceman who returned to England after the war. Her mother, Patricia Swallow, met Robert Cater in London and, according to a family member who had a very brief glimpse of Cater on one occasion, they had a short relationship.

Patricia could not take care of her daughter, so when Christine was two years old she was sent to an orphanage and later to foster homes. At age four, she was brought back into the fold when her mother married. The reunion was short: three years later, when Christine was seven, Patricia Swallow died. Raised by her stepfather, Christine was thirteen when she was told the truth about her biological father.

Not knowing her real father and having been with her mother for such a short time left huge gaps in Christine’s sense of identity. It also made her search for her roots all the more important. She contacted Project Roots and we set about looking for her Canadian family.

Soon we found Christine’s half-brother in Canada. He was thrilled to hear about his English sister, and he had quite a story to tell about their father.

After being an only child for so long, Christine Wilson now has two lovely families, one in Canada, another in Australia, who have accepted her into their lives.

It seems that Robert Cater was a married man with four young children when he went to England during World War II. When he returned to Canada, he wanted his family to move to England with him. His eldest son, being eleven years old at the time, remembers that his mother did not want to go, so his father went to England alone, leaving his Canadian family behind. In England, the father had a short relationship with Christine’s mother. He also had a relationship with another English woman, whom he married and had another family with. They emigrated to Australia in 1960.

When we found Christine’s brother in Canada, we sent him a photo. He wrote the following letter back to us.

Received your letter with Christine’s photo, she resembles my sisters, her posture and her looks, especially when my sisters were younger. You can give Christine my address and phone number. I have two sisters and one brother. My younger sister would love to hear from Christine and so would I.

In her own words, Christine wrote the following letters to us describing her feelings and gratitude for our help in the search for her father:

June 2000: I received a letter from my half-brother in Canada and have since spoken to him on the phone. I also wrote to my father in Australia who, because of his age (87) and the fact that he is finding the situation a bit overwelming (no surprise there, I suppose!), asked his eldest daughter from his Australian marriage to write back.

I received a friendly letter from her. She is just nine months older than me and her brother and two sisters are younger. It is obvious that my father had an affair with my mother whilst he was married to his second wife.

The children were all born in London, England, and they emigrated to Australia in 1960. I must admit that I had always assumed my father was a single man having a good time and did not want to be trapped when my mother became pregnant.

What a shock and what a man!

November 2000: My trip to Canada was a bit of a mixed blessing. I found it a bit overwhelming as there were so many of them and only one of me! I received a very warm welcome from everyone and I have made what I hope to be some lasting connections with some members of the family. I am in contact on a regular basis with my half-brother’s two children.

As for the family in Australia, I am in regular touch with them via e-mail and hope to visit there next year. My only regret is that I didn’t do this years ago — but better late than never, I suppose.

It only remains for me to let you know how very, very grateful I am to you both for carrying out this search for me — I think my life can never be the same again! It must give you both an enormous amount of satisfaction to reunite so many families and indeed to see so many errant fathers face up to their past, if not the responsibility for their past. Many thanks. Christine.

Postscript: In April 2002, Christine went to Australia, where she had a warm welcome from her father’s family. She stayed with her eldest sister and met with all the others and enjoyed the country very much.

Unfortunately, there was one other member of the family she did not meet, and that was her father. His health had been very fragile for over a year and he was almost ninety-one years old when he passed away, only a few weeks after Christine booked her flight.

Christine Wilson (right) with her Canadian family.

Canadian Bastard

by Sandra Connor

I was born in July 1944, to a sixteen-year-old English girl and a Canadian serviceman named Duncan Thomas Campbell. My father was sent to the Sicily landings, and by the time he returned late in 1945 or early 1946, my birth mother had already found another soldier to comfort her. Unmarried, and pregnant again with her second child, she gave up the baby girl to strangers and I was brought up by my grandparents, who raised me as their own.

Living in a small village where Canadians had their medical army base, I suppose there were many of us, but we didn’t know — and we certainly didn’t know each other. But all the things you say on your Project Roots website are true for me — the “Canadian bastard” from whom very little was expected and very little given.

At the age of nineteen I went to Canada, and within three weeks I found my Canadian birth father in Toronto. We met, and I was introduced to his wife and my half-siblings. Unfortunately, he died when I was travelling in Australia in 1968, and over time I lost touch with his family.

I now live in Canada and am the mother of two adopted boys in their early twenties. We do research into family trees and I find that I cannot get any information on my Canadian father as I have no legal right to his files. I know that he came from Nova Scotia, and that’s as far as it goes. I suppose that I should count myself lucky that we met, and I do. But I was too young to appreciate the experience, and my father died before I had a chance to ask more meaningful questions.

Being called a “Canadian bastard” was a painful experience that many war children recall with sadness to this day.

I am now looking for my English half-sister, born in 1946 and given up for adoption by our birth mother. My sister may not even know that she is half-Canadian, but I have the name of her birth father, which may help in my search.

Looking back, I can say my life has been a success story. I live in Canada, am proud to be Canadian and, at the age of sixty-one, am glad to finally read about the terrible things we Canadian war children endured.

I am thankful to Project Roots for bringing the public’s attention to our stories. We were the forgotten ones, unable to speak our thoughts for fear of upsetting our adoptive parents. What a pleasure to know we are really not “alone.”

Looking for Harry Potter

by Christine Coe

I realized that I was different from other Irish kids at quite an early age. Their mums and dads were all younger than mine, their parents weren’t so strict, and there was fun and laughter and hugs among them all.

I still loved my five brothers and sisters and my parents, even though I was scared to death of my father. He was a very strict disciplinarian who thought nothing of beating me with a stick or shoe or whatever came to hand.

There was a real stigma surrounding any child who didn’t have a dad, and I wasn’t allowed to play with the little boy who lived down the road because he didn’t have one. He was awful anyway, and was always fighting and calling my friends and me names.

One day when I was fourteen, I was standing at a table doing my homework. I looked out the window and saw that awful boy looking through our gate.

“What’s that horrible boy looking in here for?” I asked my mum.

She replied that I shouldn’t speak about him like that, as I wasn’t any different. I looked at her in amazement. She went on to say that she had something to tell me: that I wasn’t really her daughter — my eldest sister was my mum and she was my grandmother. My mind ran riot, all the lies, all the little digs from my “brothers and sisters.” Now I understood why!

All they would tell me is that he was a Canadian pilot and he was killed in action during the war, but I didn’t believe them. Somehow I was going to find my dad.

Well, their obedient, well-behaved daughter disappeared after that, and in her place was a rebellious, out-of-control teenager in the 1960s. When my “father” beat me I would scream at him that I would be happier dead and that he should kill me if that was what he really wanted.

Harry Potter, Christine’s father, in a picture taken during World War II. Her mother last saw him in December 1943, and the last thing he said was, “I will return for you.”

I was packed off to England to live with my real mum when I was sixteen. By this time she had made her own life, and I wasn’t part of it. She was good to me and bought me clothes and things, but she was terrified that someone would find out I was her daughter. She worked all hours, from early morning to late at night, so we hardly had any time to get to know each other.

Finally, one day I asked her about my dad. She told me he was a pilot and that he came from Montreal in Canada. Apparently he used to “borrow” a Leander aeroplane and dive and do loop-the-loops over her house on the weekends.

One day he crashed the plane in the field at the back of the house and was badly injured. My mum rescued him from the plane as he was unable to undo the seat belt and he had a badly injured leg and a head wound. He was court-martialled for this and sent to England for a time, but was then promoted to warrant officer and returned to Ireland.

My mum became pregnant with me and last saw him in December 1943, when she was four months pregnant. My dad was being sent home on medical grounds, but the last thing he said to her was “I will return for you.”

She waited all her life — never married, never stopped loving him.

I continued to be a rebel, met my husband and had three sons. I tried various routes to find my father, writing letters to the Canadian Embassy, making contact with the Salvation Army. I even wrote to Cilla Black, the English television host whose program involves reuniting long-lost relatives.

Christine Coe was raised by her grandparents in Ireland. She found her father’s family in Canada through the Project Roots website.

One day I went to a medium, and she told me that my father had not passed over to the other side yet and that she could see him standing on a hill overlooking the countryside. She said there was water nearby, and that he was thinking about my mum and me and wondering what had happened to us.

I went away with renewed determination to find him. Reading a magazine one day, I saw an article about Project Roots and immediately sat down and wrote to the address they gave. They sent flyers out to all the Potters in Canada, then one day advised me to write to the Canadian archives and say that I was a “buddy” looking for a friend from the war years. I did this, and back came a reply with a special number to put on my envelope. It was really hard to write the letter, how do you introduce yourself — at forty-four years of age — to your father?

I was too late. Five months later, the letter was returned with “Deceased” written across it, but there were a few scribbled notes against some questions I had asked.

After this happened, Olga put my father’s name up on their website (www.project-roots.com). I didn’t know this had been done; I had given up hope and, although I had signed to give my permission, over the years I had forgotten all about it.

Out of the blue I received a telephone call from Olga saying that yes, my father was dead, but I had a half-sister who wanted to make contact.

I cannot describe the emotions I felt. The phone rang! It was my sister, Diane. I was shaking from head to toe; the atmosphere was electric. Tears streamed down my face when I heard her soft Canadian accent. I was forty-nine years old and speaking to my sister for the very first time.

Diane flew over to England the following month and stayed with my husband and me at our house. She told me about my three other sisters, that my dad had married at seventeen and later joined the war while her mom was pregnant with their third daughter.

My letter had arrived just three weeks after he died, and his wife opened it. She said nothing to her daughters about it for nearly a year, then told Diane. Diane started to look for my mum right away: She phoned every person in the telephone book with my mum’s surname, but she was looking in Ireland — and, of course, both my mum and I lived in England.

One day she received a telephone call from her son to say he had been on the Internet: “Mom, Grandpa’s name is on the Internet. Someone is looking for him . . . an organization called Project Roots.”

It has been an amazing two years. I have now met my sister Saundra and my niece Colleen and I e-mail my sister Suzanne all the time. Emotionally it has been hard, and I have cried so much I almost have shares in Kleenex. Happy tears and sad tears.

I have a wonderful, large family. I have pictures of my dad, and it’s amazing to see the Potter family resemblance in me and my children and to know where my likes and dislikes come from.

At last I feel a whole person, not ashamed of who I am. I have the feeling of belonging, of knowing who I am.

He Was a Bigamist

by Olga Rains

Louis Burwell wrote many love letters to his English fiancée Sheila, and even though he often asked her to burn them, she never did. It’s a good thing she didn’t, because her son Robert would never have been able to trace Louis’s Canadian family and find out what kind of man his father really was.

Louis Burwell in a wartime photo. Louis was already married in Canada when he married Robert Burwell’s mother, Sheila, in England.

Sheila and Louis met in England in 1941, and what started as friendship soon turned into a love affair. But back in Canada, Louis had a wife named Florence and three young sons. That didn’t stop him. On February 21, 1942, he and Sheila married, but since Louis hadn’t bothered to obtain a divorce it was an illegal marriage and Louis was a bigamist. On October 6, 1944, a son Robert (Bob) was born in Salisbury, England. Like so many other Canadian servicemen, after the war Louis returned to Canada and was never seen or heard from again by his English wife and son.

Project Roots found out that Louis died on March 2, 1978, and was able to put Bob in touch with Tom, his half-brother. Tom was a teenager when his father went off to war, and his mother had told him all about the family Louis left behind in England. Tom was very anxious to meet Bob, and after many phone calls and letters, they finally connected in 2001.

Tom gave Bob a lot of mementos, including photos, maps and books that belonged to his father. The most precious gift that Tom gave him were Louis’s three long-service medals. This means so much to Bob, to just hold them in his hands knowing that one time, long ago, Louis held them himself.

Incidentally, Louis’s marriage in Canada nearly broke up at the time — no surprise, really — but eventually Florence and Louis made up and they stayed together for the rest of their lives.

For the full text of one of Louis Burwell’s letters to Sheila, please refer to the Appendix (page 213).

I Found Real Happiness in Canada

by Jenny Moore

My father, John, was a Canadian soldier in World War II, and he spent time in England, where he met my mother, Joan, in Bournemouth.

John and Joan planned to marry, but I was born before that happened. John was of Ukrainian origin and his parents lived in Saskatchewan. My mother’s parents were against the marriage, so they found a way to have John transferred to another part of England.

Thus began my unhappy life without a real mom or dad.

We lived with Gramma and Grampa until I was nine months old, when my mother married George, an Englishman. We moved to the house of George’s parents for a while, then we moved again. We were very poor, and George would regularly come home drunk and beat up my mother.

George was sent away, Mom went to work, and things seemed to be better when suddenly Mom took me to Oxford, where George was living, and we moved back in with him. This only ended in more trouble. George had another woman, and life there was no different. One day we escaped to the police station, and since he couldn’t hit my mother, he beat me up instead.

When I was six or seven I was sent to live with George. I never questioned the arrangement because I thought George was my real father. My main task there was to shine the brass outside the front door. I felt rejected and would wake up at night screaming from the nightmares.

One day Mom showed up with another man — Mike, an Irishman. He tried to be nice to me, but I rejected him and ran away. Life at home with George was awful and I spent much of my time on the streets. Believe me when I say I know what it is like to be hungry.

When I was nine, Mom showed up and took me to Banbury to live with a retired couple who were very nice to me. But I couldn’t settle, so I wrote to George and he took me back to Oxford. Mom didn’t like that, and eventually she took me away to live with her sister. I did not fit in and was unhappy there also.

In 1955, Mom picked me up to live with her and Mike, the Irishman, in Warwickshire. He told friends that I was his daughter. I didn’t like that, plus Mike ruled with an iron rod and Mom didn’t believe anything I told her, so there was a barrier between us.

I was not interested in school, so I dropped out. We moved to Warrington, where I worked at several different jobs and then I met a young man, we fell in love and I became pregnant. We eventually married, but this didn’t last, either. I had a nervous breakdown, we broke up and I went to stay with my Aunt Joyce. During my time there, Aunt Joyce finally told me the big secret — my real father was a Canadian soldier! George was not my father after all. I was furious!

After years of searching we found my biological father’s family. Unfortunately, he had passed away, but I have three half-brothers and a half-sister whom I have met and they all love me.

I married an older man who was good for me and my children. Harold and I went to visit my Canadian family last year and we had a wonderful time. Ironically, they never knew I existed until now. John, my father, had never mentioned having a child in England. But it doesn’t matter — I found real happiness in Canada!

Jenny Moore (centre) surrounded by her Canadian family.

The Search for My Father

by Peter Hurricks

My name is Peter and I was born in England in March 1944. My mother, Agnes Hurricks, and my father, Jack Neale, met in 1943, when Jack was stationed near Suffolk with the Royal Canadian Engineers.

Jack Neale left behind wives and girlfriends in Canada and England, finally settling in Australia.

My mother was the youngest of seven children, and as all the older brothers and sisters had left home, she was expected to stay with their widowed mother. She worked for Marks and Spencer in Ipswich, and she was twenty-nine years old and still living at home when she met Jack.

I don’t think my mother had a boyfriend before Jack, and in her own words she did “adore him.” One of my older cousins who met him when she was a teenager said he was a very charming man. He was accepted by my mother’s family and regularly went out for a drink with one of my uncles. He had parcels sent to Agnes’s home from his mother in Canada, apparently with his own particular brand of coffee and other items that were not available in Britain during the war.

Eventually he asked my grandmother for permission to marry Agnes. My grandmother approved, but said she didn’t want my mother to go off to Canada after the war. That was all right with Jack because he said he wanted to settle in England anyway. Apparently my grandmother never really trusted him, so that’s the reason why she did not want my mother taken overseas. I don’t think they actually did get engaged, because soon after this Jack was posted to Yorkshire and my mother found out she was pregnant.

I don’t believe that Jack was ever serious about getting engaged, let alone marrying my mother. It was just a ploy to have sex. Later in my mother’s pregnancy, when it began to show, my grandmother threw Agnes out of the house and she went to London to stay with a friend.

Although it may seem strange these days, an unmarried mother in 1944 was treated as a social outcast for bringing shame and disgrace on her family. There were no income-support programs as there are today. For an unmarried mother to bring up a child on her own was tough. Many such children were adopted, and it was not unknown for parents of unmarried mothers to commit their daughters to life in a mental institution, even though they were perfectly sane.

I was born in a London hospital. My mother was a very determined woman and she intended to keep me from the start. My grandmother did relent soon after I was born, so Agnes returned home and went back to her job at Marks and Spencer.

In April 1944, my mother took Jack to the Borough Magistrate’s Court in Ipswich for maintenance costs. An affiliation order was granted for Jack to pay £0.50 per week until I reached the age of sixteen, not exactly a fortune by today’s standards. Apparently he did make a few payments to my mother, but Jack’s solicitor wrote to inform her that Jack was returning to Canada. With obviously no conscience on his part, the payments ceased.

One thing that surfaced during the court case was that Jack was already married in Canada with two sons, but was apparently separated from his wife. It was presumed, however, that he was returning to his family in Canada.

After the war, I think my mother must have destroyed any documents relating to Jack, because when I got to the age when I was curious about my father, there were only a couple of old photographs left.

I started to look for Jack Neale about 1980, without making any headway. I soon came up against the Canadian Privacy Act — a brick wall that I was unable to get past. This act has denied many thousands of English and Dutch war children the right to information about their fathers, and it is still in force today. Even the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms does not allow access to this information.

Peter Hurricks as a toddler with his mother Agnes. Jack Neale was her first and only love.

It was not until 1997 when I contacted Project Roots that things started to progress. Until that date I was unaware of this service run by Olga and Lloyd Rains. Clearly, I now wish that I had heard of them earlier and the work they were doing, since, as it turned out, it might have given me the chance to meet my father.

As it was, in August 2001 Olga provided me with a very surprising and important lead that enabled me to trace a sister living close by in England whom I have now met. My sister, Jackie, turned out to be a lovely person, and when we met she recognized my father’s likeness in me. Through Jackie, I found out about my father’s Australian family and now, through our Canadian brothers, David and Wallace, I have a full picture of my father’s eventful life.

At the time of my birth, my father was thirty-one years old, and given the number of years that I had been unsuccessfully trying to locate him, there was always the chance that he had not survived. This indeed turned out to be the case. He died in 1992, aged seventy-nine, in Scarborough Hospital, Yorkshire, of heart disease. His body was cremated and his ashes scattered.

Although Jack always told my mother that it was his intention to settle in England after the war, it was a great surprise to learn how much of his life he did actually spend in England, totally unknown to me.

Jack was born John Wallace Eastwood Neale in North Vancouver on February 3, 1913, the son of Annie and Wallace Neale, emigrants from Yorkshire. Jack’s father was a plumber with his own business, and in the 1920s the family moved to Calgary.

In 1934, Jack married Hazel Ford in Calgary. Their first son, Wallace (named after Jack’s father) was born that year. At the time, Jack was a tradesman, like his father, but it was the Depression and there was little work in Canada. To get people out of the cities, the Canadian government opened up land for homesteading, and Jack and his wife were allocated 140 acres and ten dollars a month.

The land was twenty-three miles from Rocky Mountain House in Alberta. It was a hardscrabble existence: they cleared the land and built a log house, three miles to the nearest store and twenty-three miles to the nearest doctor. Their second son, David, was born in 1938.

When World War II came, it was a way out for Jack to enlist in the Royal Canadian Engineers and an opportunity to finally get some money. Jack sent money home for a while, but in 1939 he was posted to England, the money stopped, and he left his family without means of support and never contacted them again.

The family he left behind endured considerable hardship, his wife left out in the bush with two young children in the severe winter and illness to contend with. Eventually they had to move back to Calgary and stay with Hazel’s mother.

It is not known when Jack actually arrived in England in 1939, but like most Canadian servicemen during the war he was stationed on the south coast. This was where he met Nellie Godbold. On October 3, 1942, a son, Stephen, was born of this relationship. A few months later, in the early part of 1943, Jack was stationed somewhere in the Ipswich area, where he met my mother, and on March 4, 1944, I was born.

Later in 1944 my mother was informed by Jack’s solicitor that Jack was returning to Canada and that she would not be able to legally claim any further support for me. But if Jack did go back to Canada, he soon returned to England because he married Stephen’s mother at Brighton Registry Office on December 23, 1944. On the marriage certificate, Jack’s occupation was described as Sergeant M5030 in the RCE. Four months later, in April 1945, their second child, a daughter named Jackie, was born.

The family lived in Brighton and, with a partner, Jack started a motorcycle-courier business after he left the RCE. Quite commonplace today, in the late 1940s a courier business was unique and innovative and, as it turned out, quite successful.

But as the reader might judge up until now, Jack was not well known for family commitment and responsibilities; he liked to move on. Sure enough, in the early 1950s when Australia was encouraging immigration with cheap assisted passages, Jack left his family in Brighton with the aim of a new life in Australia. He promised that when he had his feet on the ground he would send for them.

Jack being Jack, he met a woman on board ship and they started a relationship, even though she was with her husband. When they arrived in Australia they set up house together.

Jack certainly got the new life he wanted, but he forgot about the family he had deserted back in Brighton. Bearing in mind that in those days there were no social or welfare programs like today, life was very tough for Stephen, Jackie and their mother. With no income from Jack, the family was reduced to living, eating and sleeping in a single room. I thought my mother and I had difficulties at times, but they were nothing in comparison to Jackie’s family. The experience of being deserted by his father apparently affected Stephen the most and was difficult for him to bear.

Meanwhile, Jack had settled in Australia and set up home with his new partner, although his wife Nellie in Brighton did not divorce him until 1967. He and his partner had a son, Robert. Surprisingly, the family stayed together for some twenty years before his Australian wife died of cancer in the mid-1970s. It is typical of Jack’s lack of concern for others that, during the last two weeks of her life when she was in a hospice, he never visited once.

Although Robert had lived with his father for a long time, Jack had never talked about his past, so Robert was totally unaware of his father’s Canadian family or me in England. Stephen, in the meantime, couldn’t settle and decided to go to Australia to see if he could join up with his father, but apparently it didn’t work out; they just didn’t hit it off together.

After Jack’s wife died in Australia, he asked his English ex-wife, Nellie, to re-marry him. He was now in his sixties and probably looking for companionship in his old age, and being Jack, thinking of himself again. Despite reservations from her family, Nellie remarried Jack in January 1977, in Busselton, Western Australia. In 1984, they returned to England and lived in North Yorkshire until his death in 1992.

I have met my sister Jackie and I would also like to meet my Canadian brothers at some stage, and indeed they would like to meet Jackie and me. My only regret is that all the time my father spent in England, knowing full well of my existence, he never once attempted to make contact. I think that says a lot about the man and his track record. On the face of it, he appears quite a selfish man, thinking mainly of himself and not at all shy about walking away from his responsibilities and the unhappiness he caused to so many others.

Jack Neale as he appeared later in life.

Tears of Torment

by Jill

My name is Jill. I was born on March 6, 1943, in a small coal-mining village in England. I was eleven years old when I found out that my real father was a Canadian soldier.

My mother was a married woman whose husband was a prisoner of war of the Japanese when she met my Canadian father. I was three years old in 1946 when my stepfather returned from the war. I will never forget his violence towards my mother, how he locked me up in cupboards and how he sexually abused me time after time when I was a child. I never understood why all this happened, and I always thought the reason he hurt us was that he had been tortured by the Japanese during the war.

I remember the first time I heard that my stepfather wasn’t my real father. I was about eleven years old, and one of the girls at school said in a nasty way, “Your father isn’t really your father.” She said she had overheard her mother talk to others about it. I remember running home that day to tell my mother what the girl had said. She told me the girl was lying and just wanted to tease me, so I went back to school after lunch believing my mom instead.

Jill never found her Canadian father, but she has a new family in Olga and Lloyd Rains.

My grandmother was a widow who had her own home, and she had to work to keep everything going. She would never get involved in any disputes or arguments between my parents. Grandmother was very frightened of my stepfather and his violence. Her house was like a refuge for both my mom and me, so whenever I could, I stayed with her. I loved my grandmother a lot. She was my best friend.

As I got older I wanted to ask my grandmother about my real dad, but I never did. Without her, I would not have existed. She took me away from my brutal stepfather, and I was afraid to hurt her by bringing up the past. I suppose my mom did love me in her own way, but she always put my stepfather first. I always felt that it was guilt over my birth. But the truth is that my mother was beaten up so often she was scared to death of him. It was a matter of survival for her.

I never felt any hate towards my mother. She suffered enough. But what I couldn’t forgive was that she wouldn’t tell me the name of my Canadian father. My mom passed away without telling me anything at all. I don’t even know if she knew his name. It is a torment I have to live with for the rest of my life.

Even after I was married and had two children, I thought she might have some respect for me and tell me something about the man who fathered me, but nothing at all. No one in the family would tell me anything about my Canadian father, so for ten long years I never saw my mother. The last time we spoke by phone, she said she didn’t want to know me.

At that time I needed her so badly because my own marriage was not good and I was trying to hold my family together. My grandmother had passed away — the only one who had understood me and given me the love I needed. My marriage ended and my life became pure hell. I longed for a father and often wondered if he had only known how I suffered, would he care?

During those ten years I always said that as long as I lived I would never let my mother in my house again. Then one day the doorbell rang, and there stood my mom and my younger sister, whom I hadn’t seen for years because she lived in another part of England. Mom and I looked at each other and I felt so sorry for her. She looked so old and sickly. I forgave her for all the hurt she caused me. I decided that I would try and make the best of things and stay in touch with my mom. This was very short-lived, because a few weeks later she had a brain hemorrhage. I was the only one at her bedside when she died. Then I knew that my mother had taken her secret to the grave and I would never know my father’s name.

Fortunately, the relationship with my sister was good because she lived closer to me now; we became very close and were able to laugh together, which made me so happy. This was also short-lived. A few years after my mother died, my sister died at the age of fifty-three.

I placed ads in different papers in the area where my mother lived at the time I was conceived. I wanted to find someone who knew my mom at that time and see whether they could shed some light on my Canadian father. I did get some letters and phone calls, and they were mostly the same — people who had known my mother and who said she went out a lot with Canadian soldiers at the time my stepfather was a prisoner of war. They also told me that my mother had had to take me to my grandmother’s house for safety after her husband came back from Japan.

The best thing to come out of the search for my father is contacting Project Roots. I would like to pay a tribute to Olga and Lloyd Rains, better known as my “Canadian mom and dad.” I am their “English daughter” and I am very proud to know them. Whilst they couldn’t find my father, they have written to me now for several years, and through their caring and support have been my pillar of strength.

I know that without Project Roots, and a great deal of compassion from Olga and Lloyd, many people would have never found their fathers in Canada. I will always be grateful for the happiness brought into my life by these two wonderful people. Olga and Lloyd could not find my happiness, but they have helped my hurt. They have given my life a meaning and I am proud of my Canadian mom and dad.

Scarred for the Rest of Her Life!

by Mary K.

This story is about my mother. I will call her Rosie (not her real name). My mother was seventeen years old in 1943 when the she met a young Canadian soldier in London, England. She and the soldier fell in love and dated for about a year. They planned to get married after the war’s end.

Just before her boyfriend was sent to the fighting lines in Italy, Rosie knew she was pregnant. Rosie was raised in a Catholic family and had a very strict upbringing. Her parents were furious that their only daughter was pregnant by a Canadian soldier, so they were going to make her pay for bringing such shame onto the family.

They made a plan, and Rosie had to obey. She was sent to a home for unwed mothers until her son, Jimmy, was born in February 1945. Rosie was forced to sign papers turning Jimmy over to her parents. Two weeks later, Rosie slipped out of sight. For sixteen years she had no contact with her family. The shame and humiliation was too great.

At first, Rosie’s parents were frantic and walked the streets of London night after night praying to find her, but they never did. For all intents and purposes, Rosie had disappeared off the face of the earth.

Some years later, Rosie married my father and had three more children, my two brothers and me. It was my dad who persuaded Rosie to look for the son she had left behind with her parents.

By the time she made contact, my grandmother had already passed away. My half-brother Jimmy, then sixteen years old, wanted nothing to do with our mother. My grandfather was still alive, and he told Rosie that her Canadian soldier had been back to see her in the hope of marriage. They had sent the young man away without telling him he had a son.

When my mother told her story to the three of us, we realized how she must have suffered when she was young and later, as a mother of three more children. She must have always thought of the baby she left behind with her parents. I asked her if she was mad at the Canadian. She said she wasn’t. He had been her first love.

My mother died young. Her life was completely destroyed by this event. It scarred her for the rest of her life.

He Just Would Not Admit He Was My Dad

by Pat K.

Dear Olga and Lloyd,

Thank you so much for returning my photograph. I am sorry to tell you that I am no longer in contact with my father. He just would not admit that he was my dad. He did send me a couple of photographs of himself, also quite a nice letter, but he just kept saying he has doubts because he wasn’t told about my mother’s pregnancy while she was four months pregnant. He said he felt if he was responsible then he should have been told first.

When I read that, I felt I just had to explain things to him, so I phoned him that very evening to tell him my mother always had a medical condition that meant she never knew of a pregnancy until she was four or five months pregnant. Well, the minute I tried to explain this he got so mad, he said that I was pushing him and he wasn’t going to have that. Just think: after fifty years he felt he was being pushed!

Anyway, he then repeated what he said the first time I called him: “What do you think you are going to get out of all this?” Before I could answer, he said, “Because I sure as hell know there’s nothing in it for me.”

I was so hurt and told him that I just wanted to know something about him. He said he just could not see any point in any of it and didn’t want to carry on with it. I was rather upset, so I just said that I understood and said goodbye.

I waited a few days, then wrote to him explaining properly on paper about my mother’s condition. I said as far as I was concerned he was, always had been and always would be my father.

My mother was not a liar. She had no reason to bring me up telling me he was my father if he was not.

To date I have never heard from him again and now sadly accept the fact that I never will. It is so sad that after all the work Project Roots did making many phone calls, writing letters, talking to so many people to find him. He did not understand your part in of all this and often told me that he did not want to hear from Project Roots anymore.

I really haven’t learned anything about him at all. He would not open up to me. I sent him two photos of my two sons and me.

I feel very sad and disappointed that it ended this way. How very easy it is for a man to say that he has doubts and there is not a thing one can do about it.

At least now I expect he thinks of me, even if not exactly warmly. I would have liked so much to meet him one time and for him to see me. I suppose for that to happen would have “rocked his boat.”

I really did not want anything from him at all.

I will always be grateful for all your time and effort in tracing him. I feel sad for you as well as for myself.

I wish you and Lloyd much success and hope you have more stories with happier endings than mine.

Thank you both for your kindness and bless you both.

Love, Pat K.

Devil’s Brigade

by Carol Anne Hobbs

My name is Carol Anne Hobbs. I contacted Project Roots in February 2002, in search of my Canadian father, Clarence William Thompson.

I was born October 6, 1943, as the result of my mother’s affair with my father, who was a Canadian soldier stationed near Croydon, Surrey, during the war. He was aware of my birth whilst serving in Italy. My mother found out he was married with children and never heard from him again.

I had been led to believe that he was killed in Italy during the war and therefore saw no reason to try to find him. During a conversation with my mother at the end of 2001, when I had mentioned how difficult it was not knowing what my father looked like or much about him, she said that she did not know for certain that he had been killed.

When I heard this, I decided to see if I could trace him. I wrote to the National Archives of Canada with his name and regiment, asking for information. At the same time, I wrote to Project Roots with my story. They put my story on the website and I waited!

I received a letter from National Archives at the beginning of April 2002, telling me he had died at Sherbrooke, Quebec, on January 13, 1995. That was all the information they could provide me with due to the Canadian Privacy Act. I was devastated to think he had died not that long ago, and thought there was no way I would be able to proceed any further. I informed Lloyd and Olga Rains, who told me to be patient . . . and I waited!

C.W. Thompson in a wartime photo. His English girlfriend didn’t know he was married with children in Canada.

On May 13, 2002, I received an e-mail from Olga and Lloyd saying, “We have found your Canadian family.” They had spoken to Lois, the wife of my half-brother Ralph, who said they were surprised but delighted with the news and would love to make contact.

I e-mailed them immediately and we frantically exchanged correspondence. They answered all my questions and sent me photographs of Dad when he was young and through all the stages of his life. I learned that I had five brothers and three sisters. Robert (Ralph’s twin) unfortunately is dead, as is Dad’s wife. My three half-sisters and two half-brothers did not receive the news so well and do not want any contact with me. That, of course, is their choice. I quickly built up a great connection with my newfound brother and sister-in-law, learning all about them and their family. We spoke on the telephone, which was really exciting, and my husband suggested we go visit them in Comox, on Vancouver Island.

We flew to British Columbia on October 7, 2002, stayed in Vancouver for two days and then set off to meet my brother Ralph and his wife Lois for the first time. We were due to meet with them in Nanaimo, where they had said they would pick us up. I was feeling so excited and nervous that I was almost sick. As we walked up the ferry stairs to start the crossing over to the Island I heard my name called. Ralph and Lois were there on the ferry!

It was a wonderful moment. Apparently, Ralph could not wait any longer to meet us. We had the most lovely visit with them for five days. We were introduced to their five children and friends, and then they took us off to see some of the Island. They were so welcoming and could not do enough for us. I have enclosed a photo.

I am so grateful to Project Roots for making all this possible. I could not have found these wonderful people without them. I am only sorry I did not get to meet my father, but our children and I have, at last, got to know our Canadian roots.

My heartfelt thanks to you all once again.

With a Deeper Meaning

by Ralph Thompson