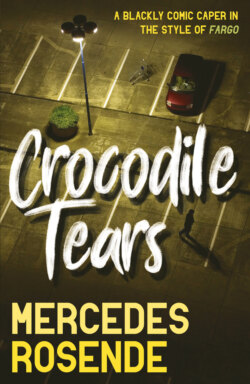

Читать книгу Crocodile Tears - Mercedes Rosende - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление37

V

The image is strong, colourful, bright, as if taken from the cover of a magazine: the wintry morning light refracts as it passes through the stained-glass windows and falls on the man kneeling on the prie-dieu, tinting his grey suit and his gelled hair, colouring his whole person red, blue, violet and yellow. Autumn is nearly over and it’s very cold outside. On the walls to the right and left are representations of the Via Crucis – of the Stations of the Cross, to be more exact – and holy music that might be Bach drifts over the pews and aisles and altars and floats up to heaven from the parish church of Las Esclavas del Sagrado Corazón, on Calle Ellauri.

Antinucci is performing the penance that Father Ismael imposed on him just a few minutes ago: one Lord’s Prayer, one Hail Mary and one Gloria in exchange for God’s forgiveness for taking His name in vain and for having three unclean thoughts about the secretary at his law practice. The shafts of morning sunlight that enter through the stained-glass windows on the east side don’t bother him because his eyes are shut, squeezed tight. He prays conscientiously, lost in his act of contrition and oblivious to his surroundings, feeling neither heat nor cold. When he recites his prayers he forgets about everything and isolates himself from the iniquitous sinful world outside; he keeps his head down, his eyelids closed, and doesn’t even hear the muffled footsteps of tardy believers, the ones who always arrive at the last 38moment, just before Father Ismael steps up to the altar in his chasuble to celebrate Mass.

Not many people attend the seven o’clock service and they acknowledge one another with a slight movement of the head, their lips forming an almost straight line; just the trace of a smile passes between those who enter on tiptoe and those who are already seated.

Antinucci finishes his prayers and crosses himself in an expansive movement that goes from the crown of his head to somewhere down near his navel and from his left shoulder to his right. He looks up and sighs, exhaling the pent-up air, expelling the sins he has now paid for, relieving himself of the final traces of guilt, which he releases with his breath. Then he fills his lungs with fresh holy air, with the smell of incense and purity.

His image, which a few moments ago was multicoloured, is now almost golden as a result of the sun shining through the yellow glass. If one of the faithful were to notice him – unlikely, as each is concerned with their own sins – perhaps they would assume the lawyer is an archangel or a prophet or at least a saint, or that his state of grace is beyond that of a normal human being. That being said, nobody appears to perceive the changing play of the light that now casts a supernatural aura around Antinucci and which, like so many daily miracles, goes entirely unnoticed.

Now free of sin and having completed his penance, paid the price he deserved, Antinucci gets up and takes his seat on the pew. He smiles to himself, undoes a button on his grey suit, pulls his trouser legs up a little and sighs again. He feels good, comforted in his guilt, part of the flock of good Christians; he knows the Lord is his shepherd and he shall not want. In fact, he wants for nothing, nothing at all. He 39looks happily at the images of the Stations of the Cross with which he is so familiar: the Son of Man is carrying the cross, he falls to the ground exhausted, three times. And he saves his favourite image for last: Christ resurrected, beautiful and whole, luminous and full of vigour, reprimands those who searched for him in the tomb. “Why do you seek the living among the dead? He is not here, but is risen!”

Father Ismael enters and, despite the sunlit church interior, the lights are turned all the way up, the music becomes louder and the liturgy begins, with Antinucci listening in a reverential attitude, his forehead tilted slightly back, although he is paying scant attention, lost in his own thoughts. Only the Eucharist prayer, half an hour later, will shake him from his self-absorption as he prepares to receive Christ. He moves his lips, murmurs a few ritual words, keeps his thick eyelids more or less closed, and then stands up and joins the line to take Communion. And he will do so as he has done since his childhood, free of any conflict with the hermeneutics of the continuity of tradition and two millennia of teaching, just like before the Second Vatican Council, because this is not one of those churches with Communist priests, full of Tupamaros and leftists, one of those where not just the priest but any of his helpers may place the Host in the hands of the faithful. No. In the church of Las Esclavas del Sagrado Corazón, the Host will be given by the priest and placed directly in the believer’s mouth, to avoid any possible blemish to the Most Blessed Sacrament.

Antinucci stands up, walks towards the nave, his eyes lowered and his arms crossed over his chest, takes his place at the end of a line of three or four old ladies, advances slowly while keeping his distance, waits his turn and takes Communion. He returns to the exact spot where he was 40sitting before, kneels with his head bowed between his hands, and prays until the Host dissolves in his saliva, prays until not one crumb is left, until he cannot feel a single particle in his entire mouth. He searches with his tongue, checks his palate, his gums, the gaps between his teeth. There is no trace of the body of Christ. He sighs, comforted.

A few minutes later, he leaves the building with its smell of incense and disinfectant and goes out into the even more intense cold of the street, ready to face the world.

Outside, Antinucci is surrounded by beggars with pale faces and outstretched hands. He hurriedly distributes some coins, averts his gaze from the beggars’ faces and walks towards his car, parked a hundred yards down the street.

He feels free of sin, he looks content and at peace.

The sound of his phone shatters the beatific moment. He brusquely takes the device from his pocket and looks at the number. His hitherto relaxed face goes tense.

“Hello. Yes, yes. I told you I want everything ready for next week. Which bit don’t you understand? It’s time, we can’t wait any longer: do it as soon as possible, without delay. Don’t put off until tomorrow what you can do today. I also told you to include Diego. Yes, confirmed, he gets out in a few days. He owes me and he’s going to have to pay off his debt. The Candyman wasn’t happy? I told you last time, I’m sick of him: do whatever it takes.” He ends the call.

He opens the door of his Audi A6 and gets in, caresses the upholstery, breathes in the smell of the material – at this point, we might ask whether this man has some obsession with leather – then starts the engine, turns on the sound system and the music gently rises. Vivaldi’s “Miserere” soothes him, fills him with peace, returns him to his state of purity.