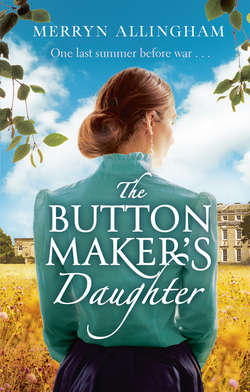

Читать книгу The Buttonmaker’s Daughter - Merryn Allingham, Merryn Allingham - Страница 6

ОглавлениеChapter One

Sussex, England, May 1914

Her father’s voice ripped the silence apart. It burst through the closed doors of the drawing room, swept its way across the hall and rattled the panelled walls of golden oak. From where she stood on the staircase, the girl could just make out his figure shadowed against the room’s glass doors. A figure that was angry and pacing. Carefully, she made her way down the last remaining stairs, then tiptoed to a side entrance. The air was fresh on her skin, cool and tangy, the air of a glorious May evening. A sun that had shone for hours still lingered in the sky and a few birds, unsure of when this long day would end, continued their song.

She walked purposefully across the flagged terrace and down the semicircular steps to an expanse of newly mown grass. Its scent was enticing and she had to stop herself from picking up her skirt and dancing across the vast lawn. It was relief that made her feel that way, relief that she’d escaped the house and its hostility. From a young age, she’d been encircled. Family discord had been a constant. Her parents’ union was what was once known as a marriage of convenience, but whose convenience Elizabeth had never been sure. Their ill-assorted pairing had been a blight, an immovable cloud which hung over everything within the home.

Uncle Henry had done something bad, it seemed. Something to do with the stream that couched the perimeter of both their estates. An act of calculated spite, her father had roared. Whatever it was, she wanted no part of it. She shook her mind free and strode across the grass as swiftly as her narrow skirt allowed, her speedy passage disturbing one of Joshua’s prize peacocks. The bird squawked at her in annoyance and flew up onto the ridge of the stone basin that sat in the centre of the lawn, fanning his feathers irritatedly. He was lucky the gardeners had yet to prime the fountain, or he might have ended more ruffled still. The warm weather had arrived without notice and caught the staff racing to catch up. The roses crowding the pergola that linked lawn and kitchen garden were already unfurling, their scent strong.

She passed beneath the grand arch leading to the huge swathe of land that grew fruit and vegetables to feed the whole of Summerhayes, and felt its red brick humming with the heat of the day’s sun. The tension she’d been carrying began to slip away and her limbs relax into the reflected warmth. Today had been difficult. Her father’s temper, always erratic, had exploded into such fury that the very walls of the house had trembled. At such moments, she was used to finding solace in her studio, paint and canvas transporting her to a world far removed from the sharp edges of life at Summerhayes. But today, painting had failed her. And miserably.

She stopped to listen, the sound of young voices floating towards her across the still air. From behind hoops of sweet peas planted amid the potatoes and cabbages and onions, she could just make out the figures of William and his companion. They were making their way along the gravel path that lay at right angles to where she stood. It was late, too late for them to be out. They were defying the curfew imposed when Oliver had first arrived to spend the long school holiday with her brother.

‘You’d better get yourselves indoors,’ she called out to them, as the boys made their way along the cruciform of gravel that bisected the kitchen garden. ‘Papa is in a towering temper and you’ll be for it if he sees you’re still out.’

‘We’ve been down to the lake,’ Oliver said. ‘We wanted to check on progress, but not much has happened. In fact, just the opposite, the site looks a mudbath.’

‘The stream has stopped flowing,’ her brother put in. ‘At least, I think that’s the problem. The lake isn’t a lake any more. It’s a mess.’

They were near enough now for her to see their grubby trousers and flapping shirts, no doubt a result of the check on progress. ‘You look hideous. If Papa sees you, you’re bound to be punished. Make sure you creep in quietly.’

‘Why is he in a temper?’

Often there seemed no rhyme or reason to her father’s outbursts and, when she didn’t answer, William said, ‘Is it Uncle Henry?’

She nodded.

‘He must have done something to the stream,’ he continued. ‘He did warn that he would if the gardeners kept taking water.’ In the muted light of evening, her brother looked older than his fourteen years.

‘I can’t see why he should,’ Oliver said spikily. ‘There’s a stream three feet deep flowing along the edge of both estates – plenty of water for everyone.’

‘You don’t know Uncle Henry,’ William said.

But if you did, she thought, you would understand his actions as perfectly consistent. Whatever Henry Fitzroy could do to hinder or destroy his brother-in-law’s plans, he would.

‘Go on, both of you. Make haste and use the side door. With luck you won’t be seen.’

‘Likely the old man will still be shouting and won’t even notice we’ve even been out.’

William was becoming cheeky. That was the influence of his more forthright friend and her father wouldn’t take kindly to it. Or to any show of rebellion. Joshua ruled him with a rod of iron and so far her gentle brother had bent himself to his parent’s will, retreating to his mother for comfort. But now Alice appeared to have a rival for his affections. Oliver had become William’s closest confidant. Her brother had been wretched at school, a school their father insisted he attend – until Oliver had appeared at the beginning of the winter term. But Olly, as William called him, had proved a saviour and the change in her brother was astonishing. She could see why they liked each other, why they had come to depend on one another. At school, they were both outsiders, despised by their fellows and teachers alike: William the son of a button manufacturer and Oliver, the son of a Jewish lawyer.

‘Are you coming back with us?’ The light was fading fast and William had begun to look anxious.

‘In a short while. I’d like to take a look at the lake for myself.’

‘You’ll need boots,’ her brother warned.

‘And a dress that’s a few yards shorter,’ Olly quipped.

‘Don’t worry. I’ll not be long.’

She shooed them away with a wave of her hand and carried on along the narrow gravel path that skirted the various outbuildings: past the boiler house, the bothy, the dark house that forced Summerhayes’ rhubarb and chicory and sea kale, and, finally, the head gardener’s office. She glanced across at the huddle of buildings. Nestled together, they made a charming picture but afforded little comfort. The one time she’d visited – for some reason, she had found herself in the tool shed – she’d seen immediately that light was not to be wasted on the workers. The interior had been gloomy, with small windows and little daylight. It was damp and cold, too, since only Mr Harris enjoyed a fireplace, his one luxury in a room of bare boards and battered furniture.

Through another grand brick arch and into the Wilderness. That was the name she and William had given it. Her father insisted it should be called the Exotic Garden but from the start it had been the Wilderness to them, a place where they spent as many hours as possible, hiding from their nursemaid or later their tutor and governess, and hiding from each other.

She came to an abrupt halt. Something was wrong. She stood for a moment and then realised what was missing: she should be hearing the splash of water against stones. A stream flowing to her left, flowing down from the encircling bank and into the lake. But there was no sound of water, no sound at all. The garden seemed to have come to a standstill and an uncomfortable quiet reigned. She took a long breath, then walked through the laurel hedge, the living arch that marked the entrance to her father’s most cherished project, and saw immediately what William had meant.

A little of Joshua Summer’s plan had already been realised. A flagged path had been laid to provide a gentle promenade in a space that was made for the sun, and aromatic herbs planted in the cracks between the paving stones. Beyond and behind the path, bed after bed of Mediterranean plants would find their home and eventually flourish in profusion. On one of the long sides of the lake, a small summerhouse made of Sussex flint and stone had been built, its wooden seats looking out across the water to the terrace and the pillars of what would one day be a classical temple. She could see its foundations from where she stood. They were complete and several of the pillars had already been fashioned and were lying to one side, like giant marble limbs that had somehow become detached from their body. But the magnificent lake, designed to reflect the temple’s elegance, was now little more than a muddy pond, and the statue her father had commissioned – a dolphin whose mouth spouted a constant stream of water – rose, strange and solitary, from out of the ruin.

Somewhere a dog howled. It was an unworldly sound funnelling its way to her through the thick evening air. The hairs at the nape of her neck stood to attention, but almost immediately she realised the noise had come from Amberley, from one of her uncle’s hounds, and gave it no more thought. Picking her way along the flagstones, she had to lift her skirts clear of the sludge before gingerly circling the large oval of dirty water. She had reached the west corner of the temple when a noise much closer to hand startled her. Wildlife in the garden was prolific and for a moment she thought it must be a fox moving stealthily through the tall trees that grew behind the temple, making his way perhaps to the Wilderness to find his tea. But then she heard a cough. A man. And footsteps, soft but unmistakable. The lateness of the hour was suddenly important. She shouldn’t be here. Her mother had warned her often enough that the estate was not secure, that there was nothing to stop a curious passer-by from scaling the six foot wall and enjoying Summerhayes for himself. She took a step back, poised to flee. The gloom of dusk had settled on the garden and the overhanging trees behind the temple workings cast an even deeper shadow across her path. There was a crackle of twigs, a swish of undergrowth.

She turned abruptly.