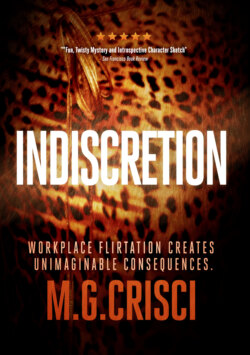

Читать книгу Indiscretion - M.G. Crisci - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

8.

ОглавлениеEnter Dr. James Sherry.

The next six months were quite painful.

MJ morphed into an entrenched agoraphobic as soon as we arrived home. He wouldn’t leave his bedroom for the first two weeks, which created the need for full-time help to cook for, wash, and feed him. Lauren took vacation leave in the middle of her busiest time of year to be near him. The psychiatrist MJ had identified refused to make house calls, which led Lauren on a professional search to find a suitable replacement, someone skilled at deeply entrenched cases.

Through a series of referrals at the hospital, Lauren was introduced to Minnesota-born Dr. James Sherry, a mid-forties psychiatrist with a gentle manner who had himself suffered from panic disorder during a particularly trying time in his life. After a few sessions in which MJ rarely spoke, Dr. Sherry declared privately, “Getting MJ back into the game of life is going to be a difficult challenge. He is intellectually brilliant but unbelievably stubborn. That’s not an easy combination to deal with.”

Guilt-ridden, we asked the obvious. “What did we do wrong as parents?”

Dr. Sherry’s response was less than comforting. “First of all, you need to understand you did nothing wrong. MJ is suffering from an extreme case of acute panic disorder. Until the last twenty years, psychiatry spun its wheels trying to identify the root cause of the individual patient’s affliction, using antidepressants as a crutch. Now we understand that cases like MJ are partially biochemical — something has changed in the fundamental makeup and order of his brain cells.

“Consequently, he reacts negatively to certain stimuli he feels he cannot control. Those stimuli vary by patient. For some, confined spaces cause anguish; for others, it’s loud noises at sporting events; and for others, it’s about suffocating crowds.”

“What exactly is MJ afraid of?”

“Unless you have had one of these attacks, it is hard to describe, much less empathize. The patient thinks he is going crazy, or he’s having a heart attack. They are unable to maintain control. Life becomes a distant haze. Their heart pounds; their skeletal structure becomes limp; they can’t even hold a glass of water. The actual attack may last only a few minutes, but when we are in the eye of the storm, it feels like forever.”

I wondered if Sherry’s description was a subconscious slip.

“Mr. Ruff, I can smell the wood burning,” smiled Dr. Sherry. “Yes, I have suffered from acute panic disorder. It became all-consuming. I had to take a sabbatical from my practice.”

“How long?”

“Four years.”

Looking around at the doctor’s family pictures, I couldn’t help but ask, “How did your wife and kids come to grips with your condition?”

“They didn’t; she divorced me and took the kids.”

“How did you get cured?”

“APD is like alcoholism,” Sherry responded. “Once inflicted, you have to stand guard for the rest of your life. Some days are better than others. But living with it is certainly better than the alternative. We’ve also learned that trying to discover what causes the change is a professional waste of time. Changes in brain chemistry are irreversible. The only known cure is to rebuild your self-confidence by slowly regaining control of the situations that caused the attacks in the first place.”

“How long does that process take?” asked Lauren, now fully realizing the gravity of the situation.

“Depends on the patient. Initially, some patients try to control their entire environment; eventually they realize that’s not possible.”

The more I listened, the more upset I became. “Can you at least give me a damn time frame?”

“Simple case, two to three years. Worst case, a decade or so.”

“Jesus Christ!”

“I realize your son’s condition is quite a shock, but there is some good news in all this. No patient has ever died or even experienced a heart attack or stroke from this condition.”

“So, where do we go from here?” asked Lauren.

“You understand, for the moment, that he has to be treated as if he is disabled? He cannot work. He needs regular counseling, initially with the two of you, eventually by himself. He needs medication and a predictable course of rehabilitation. In other words, he can be institutionalized, or we can attempt episodic home treatment.”

I bristled. “No son of mine needs institutionalization!”

“Calm down, honey.”

Sherry responded calmly, “I was going to suggest we start by treating him at home. Let’s see if the familiar surroundings help matters.”

~

After twelve months of intense treatment and a few hiccups, MJ made some progress. He was now able to drive about a quarter of a mile to the grocery store, buy food for himself, and make a meal.

During that time, his brother Bart tried everything he could think of — from playing Madden NFL video football to gentle conversations recalling fun times and pleasant memories to stern admonishments about MJ’s need to “get out of his funk.” Bart desperately wanted his childhood role model to snap out of his mental malaise. Nothing worked. In time, Bart just stopped trying.

At age 58, I found I was feeling quite sorry for myself. We were restricted geographically. MJ had given up his apartment in Darien and moved into Southport full time. It was like having a child return home. MJ was always on the phone checking our whereabouts to avoid having a relapse. I was utterly frustrated, and it showed. Dr. Sherry suggested we practice driving to the airport. I’ll never forget that first exercise. When MJ realized we were on the Throggs Neck Bridge across Long Island Sound, he completed wigged out, and then he cried all the way home.

At a subsequent session with Dr. Sherry, it became clear that MJ blamed much of his pain on my impatience, insensitivity, and overbearing personal expectations. He, the doctor, and Lauren all agreed Lauren should be MJ’s “safe person,” the person who would act as surrogate shrink when he experienced emotional duress, which was most of the time.

Effectively, I became a man without a family.