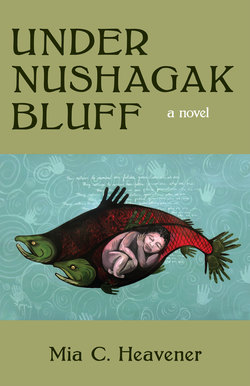

Читать книгу Under Nushagak Bluff - Mia Heavener - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Four

ОглавлениеAlthough her mother gave her long, tired glances, Anne Girl secretly met with John. They walked up and down the beach, creating a space for themselves between the cannery and the bluff side of the village as they searched for new paths when the tide was high. John told different types of stories, ones that filled Anne Girl’s head with black and white images, like those she saw printed in the Life magazines at the cannery store. Her favorites were the summer covers that usually showed a girl in a fitted swimsuit with bare shoulders looking out to the ocean. It made her laugh to think of herself in such a getup, trying to pick fish. Yet, the images always fascinated her, and she pictured them when she talked to John. She saw them in his words when he described his home and family in Seattle. And the more John talked, the easier it became to fit herself into his stories as if she came from the same roots. He was Norwegian, with a grandfather as old as the canneries and straight from Norway. John didn’t have to tell that story twice. Even with his soft hands, she knew that Norwegians were workers. That’s what every village woman on the bluff said. The cannery was built by Norwegian and Swedish hands. You can’t let a worker go, even if he doesn’t know what he is doing. Even Marulia couldn’t disagree with that. Yet, Anne Girl wondered why someone who traveled so far would decide to remain in her village, where the winter quiet becomes hungry and you have to yell just so you know that your voice still works.

They walked toward the cannery and onto the boardwalk where the buildings loomed from on top of wooden decking. The cannery had shut down weeks ago, and there was a new stillness in this part of the town. Although all of the windows were boarded up and the doors locked, she could feel the echoes of the cans of salmon being steamed shut. She could hear the seagulls fighting for the last bits of gills.

“You’re quiet today.”

Anne Girl nodded and took John’s hand. Before she had left the house, she had helped her mom into bed and pulled the covers up to her chest. Marulia told her to bury her on high ground and to make sure all of her clothes were burned. She had made Anne Girl promise to marry a fisherman, someone who knew how to mend nets with one hand. Until that moment, they hadn’t mentioned death before, and Anne Girl had found herself without a response. She nodded and moved to put more wood in the stove, because her mother continued to repeat that it was too cold.

“The temperature dropped in the last few days. It’s going to be a cold winter,” Anne Girl told John. “Did you see how fast the berries came this summer? I couldn’t pick them quick enough. They were falling into my bucket. Just so you know, my kass’aq, when the berries ripen early, then everything shifts.” Anne Girl motioned with her hands, moving them side to side.

“Yeah, that’s what Frederik says. He says you haven’t had a really deep freeze in a long while.”

Clearing her throat, Anne Girl pulled John toward the boat house. “He always says that. He hasn’t been here long enough to know. Come, I’ll show you where we used to sneak into the boat house as kids.”

They weaved between the alleyways, passing the bunkhouses, the mess hall, the net loft, the small clinic with a front porch painted white, to the heart of the cannery with the boat house and mechanical rooms. It was here where the rumble of the cannery generators grinded their wheels. It was here where all the fishermen stored their equipment and spent hours painting and repairing their boats before the season began.

Anne Girl walked to the side of the boat house and began tapping the sheet-metal until one panel rattled louder than the others. She pulled the tin sheet from the wall, revealing a narrow, black hole, and grinned.

“Kind of small. You fit through there?” John asked.

“Used to. Had to hold my breath to get by the metal edges or they would cut deep.”

“What did you do in there?”

“Play. The cannery men always left good things to play with. Once they left tools, so I took them home.” A smiled spread on her face. “Do you want to play now?”

John reached for Anne Girl’s waist. “When are you going to let me meet your mother?”

Anne Girl pulled away and let go of the tin flap. She stared at him. Of all the things he could say to her now, he had to ask about her mother! But as he stood waiting for her answer, Anne Girl realized that she could neither lie nor tell the truth. She wanted to tell him that he would never meet her mom, that Marulia cringed every time Anne Girl mentioned his name, and that she asked out loud whether John could hunt or fish. “Is he good for anything?” Marulia wanted to know.

“Maybe soon,” Anne Girl said, and she pulled at the flap again. She looked up into John’s eyes and felt the unexpected urge to pull him down on her so that his long, narrow figure would suffocate her loss. And when her body was mashed up against his, she would enter a space where the restlessness would finally subside. Where she could find quiet and breathe again. Anne Girl traced his waistline with her finger. “The net loft is warm year round. I know another way to get in there. But keep your arms close to you, so you don’t get cut. ”

Afterwards, they lay side by side on top of stacked nets, exhausted and breathing hard. Anne Girl rolled over and smelled the mixture of fish and sweat. John’s hair was frosted with scales that glimmered in the darkness, and she picked them off one by one. “Frederik will wonder what you’ve been up to,” she said, and began to giggle. “Make sure you tell him that you were working hard.”