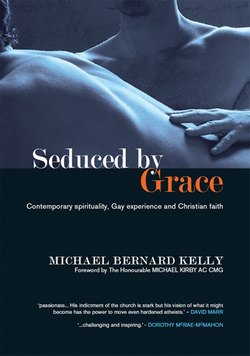

Читать книгу Seduced by Grace - Michael Bernard Kelly - Страница 6

Foreword

ОглавлениеThe Honourable Michael Kirby AC CMG

Readers will have different reactions to this book. I know what my long-suffering partner of four decades, Johan, would say about it: ‘Why doesn’t he get over it? If the institution of the Church hurts him so much, why not give it away? Why not explore some other avenue of spirituality? Like Buddhism? Or Theosophy? Or perhaps just become an old-fashioned humanist and rejoice in common human goodness? Why does he torture himself with the perceived cruelty of his Church in its dealings with him?’

The author of this book, a son of Melbourne, worked for many years for the Roman Catholic education system that nurtures a large and growing proportion of Australia’s schoolchildren. But when he openly revealed that he was homosexual, he had to go. Priest or teacher, sister or gardener, there is, it seems, no space in the Church or its institutions for open people like him. True, if they remain silent, they do not confront Church leaders with the ‘inconvenient truth’ of their sexuality. It is the ‘intrinsic tendency to evil’, that is bound up in their sexual orientation that supposedly requires this modern vow of silence. Of course, it is a ‘vow’ that promotes hypocrisy, deceit, bitterness and self-loathing. For many, the ‘vow’ ends up being a greater burden than the knowledge that, in this particular, the individual is a little different from the majority of humanity.

‘No. No. You must understand’, I would say. ‘He stays with his Church because it is part of his being. It is a link with his most beloved family members and friends. It brings comforting memories of his safe and secure days of childhood. It contains people who are good and noble and do wonderful things for many. Above all, the Church is the ultimate guardian of the most precious message of a divine guide to us on Earth – Jesus’. So I would tell Johan. ‘He cannot let it go because of love. He refuses to let a few powerful old men in frocks divorce him from the Faith that he learned as a boy and that is part of his very essence. He truly believes that Faith. And he knows that it is a religion of love and equality, with respect for the dignity of each and every one of us. He knows (or at least hopes) that we are going through a bad patch of unkindness, power-play, hypocrisy. When the central message of the religion is lost, drowned out by angry voices and a few selected passages of Scripture, read in isolation from their context and seemingly deliberately misunderstood’.

‘How can you believe all this?’ Johan will reply. ‘How can you, and he, obviously very intelligent men, take seriously the absurdities of your religion. Let’s face it. It has always been oppressive. Oppressive to women and unequal in the space it allows them in the Church. Oppressive to people of colour, to slaves, to indigenes under the conquering Europeans. Oppressive to gays. I just scratch my head and cannot understand why you and he persist. Give it away. It will make you feel more at peace. By the way, it will also make those narrow minded bigots feel a whole lot happier. You can meet the ‘good and noble’ types in other contexts. And anyway, as the author himself found in the Internet chat room which he recounts, with the inquisitive priest ‘Bill’, some of the harshest oppressors in the Church are gay themselves. They are struggling with demons in their own minds. Cut yourself clear from them. It will be better for all concerned’.

I did not grow up in the Roman Catholic tradition of Christianity. Some things in this book appear alien to my understandings. The holy water. The Marian prayers. The seeming fear of the Vatican. The close attention to Papal encyclicals. The ‘sacred gift’ of celibacy these last 1700 years. For me, the Church of my childhood was the Church of England, now called Anglican. It is, as the author describes it, a church that daily ‘has our fights for us’. There were always flags near the altar of my church. God, King and country were intimately associated in those boyhood days of the British Empire. Yet it seemed a pretty tolerant space. Inclusive even. There always had to be room for the catholics and protestants in the post-Reformation English Church.

I watched with expectation the outreach of my denomination in the ordination of women priests and the consecration of women bishops. I saw its growth in Africa and other lands of people formerly oppressed. Yet, lately, those who were oppressed seem to have turned their new-found power on the sexual minorities within Anglicanism. Like some of the leaders of the Roman tradition, described in this book, a few Anglican leaders have attempted to snuff out the ever-so-tentative moves to welcome and accept gay people to an equal place at the Table of the Lord.

In Australian Anglicanism, there are Church leaders who oppress and trouble my spirit, just as the author’s spirit is troubled. They deny the pulpit to voices they see as discordant. They refuse engagement with new ideas. They turn their backs on the rational tradition of the Christian Reformation. Little wonder that Bishop John Shelby Spong calls for a new Reformation in Christianity. One that will reach out to the alienated and restore the true universality of the Christian Communion.

Michael Bernard Kelly is a powerful writer. Notice how, in many of the short and painful essays in this collection, he uses the rhetorical device of repetition. Words and phrases are repeated, like the chants of the monks of old and the beautiful collects of Cranmer’s Common Prayer. I understand and share his pain, without necessarily agreeing with all of his tactics. I am not, of course, competent to assess the response of his Church. Doubtless it would have its own viewpoints. However, I am thankful that great churchmen of our age, like Bishop Desmond Tutu, are now lifting their voices to demand an end to the oppression of sexual minorities. In Nairobi, in January 2007, the South African Nobel Laureate Tutu told a conference:

I am deeply disturbed that in the face of some of the most horrendous problems facing Africa, we concentrate on ‘what do I do in bed with whom’. For one to penalise someone for their sexual orientation is the same as penalising someone for something they can do nothing about, like ethnicity or race. I cannot imagine persecuting a minority group which is also being persecuted.

Sad that it took apartheid to teach a Christian Bishop that lesson. Happy that he learned the lesson and now teaches it to millions.

The answer that Michael Bernard Kelly and I give to Johan is a simple one. We love and accept the universal message of Jesus. We refuse to let it go. We deny anyone the right to take it from us. We do not for a moment accept that we are beyond the pale. We know that, in the end, the universality of love and belief will be restored. Nothing else would be rational or just. Nothing else would be true to the central message of our Faith that so many good people accept and live by. Everything else is peripheral. In the words of the Talmudic scholar, although we may not see our conviction fulfilled, neither are we free of the moral obligation to tell its message.

1 October 2007

Michael Kirby