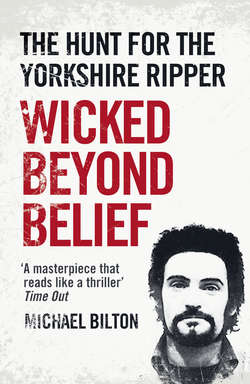

Читать книгу Wicked Beyond Belief: The Hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper - Michael Bilton - Страница 8

PREFACE

ОглавлениеPoor Wilma. A strong-willed and feisty woman, she was determined to live life on her terms. It was either her way or no way. A driver picked her up. She agreed, late one night in October 1975, to a risky proposition from a total stranger: sex for a fiver. With a bunch of small kids to care for on her own, this was how she got by. And now? She was dead, the first publicly acknowledged victim of the Yorkshire Ripper.

Her body – shrouded by a low-hanging mist at the edge of a football field – was found early the next morning. The damp and miserably cold vapour clung as grimly and insistently to the frail corpse lying on that grassy bank as it did to the rest of the city of Leeds that autumn.

The fog was almost a symbol of the terror and fear that was to come. It seemed to hang perpetually over the North of England for some considerable time, like some mysterious and impenetrable miasma. And it never lifted for five long years. It enveloped and chilled the lives of millions who lived there, men and women, young and old. But most of all women.

A year later, MPs in the House of Commons voiced deep concerns about a major police investigation that turned into a fiasco with tragic results. There was little or no glory for the detectives who had led the hunt for the notorious killer called the ‘Black Panther’, who turned out to be Donald Neilson from Bradford – a vicious and cold-blooded criminal, wanted for the murders of three sub-postmistresses and the kidnapping and murder of heiress Leslie Whittle. As in the Yorkshire Ripper case there had been an all-important hoax tape-recording that threw detectives off the trail of the real killer. Like the Ripper case the hunt involved several police forces. Like the Ripper case there was a great deal of resistance to calling for help from outside, and when the end came it was two bobbies in a patrol car who made the arrest, not realizing they had caught a vicious killer. Finally, as in the Ripper case, when it was over there was a need for scapegoats: the officer in charge suffered the humiliation of being shifted sideways – out of CID and into uniform.

Some MPs demanded an inquiry into the mismanaged conduct of the Black Panther investigation, but the then Labour Government refused. Home Office Minister Dr Shirley Summerskill told Parliament the case:

has been discussed by chief officers of police collectively and I am quite sure they are fully aware of the need to learn any lessons which may be learned from such an investigation … the fact that a particular investigation is a matter for discussion by chief officers of police is a reflection of our system of policing in this country. The local control of police forces is an essential element of that system. Chief constables in this country, unlike some continental countries, do not come under the direction of a Minister of the Interior, in the enforcement of the law. The responsibility of deciding how an offence should be investigated is for them and them alone.

But when the Yorkshire Ripper case concluded five years later in 1981 it was abundantly obvious that Britain’s chief constables, and the police service as a whole, had disastrously failed to learn the lessons of the Black Panther investigation. Government ministers, senior officials at the Home Office and the Government’s law officers saw little merit in an agonizing public debate over the Yorkshire Ripper investigation. MPs’ demands for transparency were turned down, and there would be no public inquiry. But there was a major shock in store for the criminal justice establishment when Sutcliffe’s trial opened at the Old Bailey in London.

The prosecution, led by the Attorney General, Sir Michael Havers, pushed for a suspiciously speedy hearing, accepting a guilty plea to manslaughter from the accused, Peter Sutcliffe, on the grounds that mental illness had diminished his responsibility for his crimes. It all seemed done and dusted. The court proceedings would be over within half a day because both defence and prosecution were in complete accord.

However, they had not reckoned with the Judge’s reaction. To his very great credit Mr Justice Boreham refused what was in essence a plea bargain. Instead he ordered a full and open trial by jury to determine whether Sutcliffe was mad or bad. The jury would hear the evidence and decide for themselves whether Sutcliffe was guilty or not guilty of murdering thirteen women; or was guilty of manslaughter because he did not know what he was doing. Justice demanded that this gravest of matters should not be swept under the carpet. Ultimately he was convicted and given a thirty-year minimum sentence.

It seems extraordinary that nearly thirty years later the arguments about Sutcliffe’s responsibility for his crimes had never gone away. A new team of lawyers came back with a vengeance in 2010, when the Yorkshire Ripper went to court saying that having served his minimum sentence, he was entitled to know when he would be released. For the public at large the very idea seemed preposterous, incredible even; but Sutcliffe’s psychiatrists at Broadmoor secure hospital had declared their great success in treating him and were arguing that all along he had suffered from mental illness, meaning that his responsibility was diminished when he committed his crimes. Sutcliffe’s lawyers argued this meant he was entitled to a reduction of his minimum sentence.

All this was made possible because the European Court of Human Rights in 2002 ruled that judges – not the Home Secretary – should decide how long a lifer spends in gaol. So once again Peter Sutcliffe stood at centre stage making headlines, once more his activities invaded the psyche of the British public, fearful that the courts might actually believe he was almost an unintended victim of the Ripper case and set him free. Politically, the very idea was quite toxic, and the Prime Minister and Justice Secretary were both put on the spot, as an anxious public demanded to know: ‘Is this man actually going to be freed?’

Dealing as it did with one of the most notorious killers in British criminal history, the Yorkshire Ripper case raised crucial questions. Before her death, Myra Hindley – the 1960s Moors murderer of several children – had routinely tested the patience of the public with her woeful cries that she had served her time. Now another notorious serial killer was following suit. Thirty years before, the thought that Sutcliffe would ever be freed would have seemed utterly fanciful. Then Britain woke up and found that three decades had slipped by, the thirty-year minimum sentence passed at the Old Bailey in May 1981, was almost at an end – and now the law was different.

After Sutcliffe was snared in January 1981, there were enormous issues raised which needed truthful answers, especially about the failure of the police to solve very serious crimes. Today, such matters would be openly debated and inquiries held. But back then the public at large, the families of the Yorkshire Ripper’s victims, the media, the taxpayers of West Yorkshire, MPs, even seasoned high-ranking detectives closely involved in homicide investigations, were never given answers. The key questions had been: Why did it take so long to catch this terrible serial killer? Had the police been up to the task? Who should be held accountable for mistakes that were made? The reason for this was the huge sensitivity surrounding shocking errors in the investigation.

Sutcliffe’s official toll was thirteen dead and seven attempted murders. We now know that he attacked many more women and that there were many opportunities to apprehend him which were tragically missed. In recent times, public disquiet over the Stephen Lawrence murder in London and the multiple killings by Dr Harold Shipman resulted in full and transparently open inquiries. In contrast, public disquiet over the Yorkshire Ripper investigation was flatly dismissed with platitudes that everything would be better in future. No open inquiry took place. Serious questions were posed but the answers only emerged behind closed doors. A high-level secret inquiry had recommended revolutionary changes in the way the police investigated serious crime, and yet openness, transparency and the acknowledgement that the public had a perfect right to know the truth about the police hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper were nowhere to be seen.

In January 1982, seven months after Sutcliffe was given twenty terms of life imprisonment, the then Home Secretary appeared before Parliament to announce the findings of an internal Home Office inquiry by one of Britain’s most senior and respected policemen, Mr Lawrence Byford. He had brilliantly investigated what went wrong with the Yorkshire Ripper case, but William Whitelaw, the Home Secretary, refused to publish Byford’s penetrating report which stripped bare all the mistakes that were made. Instead a brief four-page summary of its main conclusions and recommendations was placed in the House of Commons library. This summary only scratched the surface of the body of crucial facts garnered during Byford’s six-months-long inquiry by an eminent team of senior British police officers and the country’s leading forensic scientist, which was a model of its kind.

In a quiet and unsensational way, Byford’s report laid out its unvarnished and unpalatable truths in more than 150 closely typed pages. It contained much extraordinary detail. Such was the confidentiality surrounding the report that it was printed privately outside London and not by Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. No senior civil servant, not even the Permanent Secretary to the Home Office, was allowed to view a copy until Mr Byford delivered it personally to William Whitelaw. As one of Her Majesty’s Inspectors of Constabulary, Byford knew that in preparing the report he and his inquiry team had a grave duty to perform not merely for the benefit of the police service, but for the country as a whole.

Byford and his team did not shirk their responsibility. The changes his report recommended were truly ground-breaking, so much so that a cynic might say that if there had been no Yorkshire Ripper, it might have been well to invent him, as the sole means to force dramatic but profoundly necessary changes upon a creaking police service.

As a staff writer for the Sunday Times based in Yorkshire from 1979 to 1982, I became closely acquainted with some of the detectives, pathologists, forensic scientists and outside advisers who were most closely involved in the Ripper case. Over the succeeding years many of the figures principally involved in the investigation spoke to me off the record about their work on the Ripper Inquiry and how it personally affected them. Some, like Dick Holland and George Oldfield – key members of the Ripper Squad – went to their graves feeling they had been scapegoated. Others felt their actions and motives were totally misunderstood. Until I had got my hands on a copy – some seventeen years after it was written! – the Byford Report had remained an official secret. It was not till the summer of 2006 that the Home Office at last released the report and some of their own files, following an application under the Freedom of Information Act. Britain’s most senior detectives, those with responsibility for investigating major crimes, had not been allowed to study this vital account of what had gone wrong.

I read the Byford Report for the first time in 1998, and realized that here was a sensational story. Answers now fell into place. All too many mistakes had been made, and a good number of those closely involved with the most important criminal investigation in British history agreed that the full story deserved to be told so that the British public – and more urgently, future generations of detectives – could learn its lessons. Hence this book.

For me the real story was as thrilling and chilling as any crime novel, containing as it did such complex characters and so many twists and turns. The more I got to know the detectives the more fascinated I became by who they were – and why it was that some of them had got it so disastrously wrong. These were not one-dimensional figures, and I endeavoured, as I wrote the narrative, to put flesh and bones on some of them so that they could be seen for what they were, human beings trying to do a difficult job.

Some were clearly better than others, but I have no intention of pillorying anyone for mistakes that were made. As a writer you cannot examine how an institution works and forget the very people who make up that institution. When the institution fails you need to look at its whole structure, which in the case of the police service starts with ordinary policemen and women on the beat and progresses upwards through a hierarchy, beyond the chief officers, to the Inspectorate of Constabulary, the Home Office civil servants in the Police Department, and then the ministers in charge, ending with the Home Secretary.

You had to live in the North of England to comprehend how such a terrible series of crimes terrified a major part of the British Isles. Still today, what most people want to know is: What went wrong? Why did it take so long to catch Peter Sutcliffe?

Even thirty years later, and allowing for the benefit of hindsight, some of what has emerged about the investigation seems truly shocking. As with other notorious murder cases, when the subject of the Yorkshire Ripper is mentioned it brings dreadful memories flooding back for those most intimately involved. The families of Sutcliffe’s victims deserved to know what really happened during that awful period when a beast called Peter Sutcliffe roamed the North of England creating outright terror. They also needed to know that some good came out of that terrible era and that lessons were learned about complex cases.

The police officers trying to track down this utterly ruthless killer were decent and honest men. Amid the chaos that gripped the investigation there were some brilliant detectives. Most were totally committed, but tragically some, just like the police service for which they worked, were way out of their depth. The British police have an extraordinary record in solving homicides, and G.K. Chesterton’s reflection that ‘society is at the mercy of a murderer without a motive’ is now only partially true. Random prostitute murders are still every senior investigating officer’s worst nightmare, but in recent times we have seen successful investigations into the serial killing of call-girls in Suffolk and a fresh round of prostitute murders in Bradford. It is very different now from that period in the last century when the hunt for the Yorkshire Ripper was so complex and protracted that it simply overwhelmed the West Yorkshire Police. Many of the detectives involved paid a high price – ruined careers, ruined health, ruined marriages – and in a few cases it led to their premature deaths.

Now as then, I am not remotely interested in Peter Sutcliffe, the individual. Many have asked whether I ever wanted to interview him. The answer was a resounding. ‘No!’ What could he tell me that I didn’t already know – that he was a sick and perverted killer who got powerful sexual thrills from having women at his mercy as he slaughtered them? For me it would have been a worthless exercise to ask Sutcliffe serious questions and expect believable or valuable answers. The detectives though were another matter completely. I was intrigued by them as people, and by the service for which they worked. I wanted to put the reader in their shoes, as they attended a murder scene or an autopsy or a press conference. There can be no freedom without a system of laws and we need these dedicated men and women to enforce those laws. The British police service remains one of our pivotal institutions; it safeguards much of what we take for granted.

More than three decades after attending his trial in Court Number One at the Old Bailey in May 1981, I resolutely maintain that there was only a single villain in the Yorkshire Ripper case. It was, and is, the monstrous and twisted individual I saw giving evidence in his own, highly implausible, defence of the indefensible. Peter Sutcliffe was, and remains, wicked beyond belief and it will come as a comfort to many that some of our most senior judges, led by the Lord Chief Justice himself, seem to agree with me.

Michael Bilton, January 2012