Читать книгу Depth of Field - Michael Blair - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

chapter one

ОглавлениеIt was Tuesday, a little past nine in the morning. The fog outside my third floor office window was so thick you could scoop it up with a shovel and cart it away in a wheelbarrow. Unusual for Vancouver in June — virtually unheard of, in fact — but given the winter we’d just been through, nothing would have surprised me weather-wise. The environmentalists blamed it on global warming. The conspiracy theorists blamed it on scalar weaponry run amok. I just groused.

I was alone in the studio, feet up — definitely not unheard of — coffee cup nestled in my lap, wondering where the hell everyone was, when I heard the elevator rattle to a stop and the door bang open. I dropped my feet to the floor, startling Bodger, who’d been cat-napping on the sagging leather sofa against the opposite wall, tattered ears twitching as he dreamed of fat, complacent mice — or the cat treats I kept in my desk drawer, which were a lot easier to catch.

“Well, it’s about bloody time,” I said, as I went into the outer office.

“Pardon me?”

“Oops,” I said, looking at a shapely blonde. “Sorry. I was expecting my associates.”

“That’s quite all right,” she said.

The top of her head was level with the tip of my nose. She had sharp, emerald-green eyes, nice cheekbones, and a wide, generous mouth painted the colour of cherry Jell-O. I guessed she was thirty-five, give or take.

“Can I help you?” I asked hopefully.

“I’m looking for Thomas McCall,” she said, surveying the chaos. We were relocating on the weekend and the studio looked as though a giant child had thrown his toys about in a fit of temper.

“You’ve found him,” I replied. “What can I do for you?”

“I’d like to hire you,” she said. Her voice was light and slightly scratchy, as if her throat were lined with fine sandpaper. A smoker, I thought, although she didn’t smell of tobacco. In fact, her scent was faintly reminiscent of marshmallow, simultaneously sweet and musky and powdery.

“I’d like to be hired,” I said. “Never mind all this. We’re in the throes of moving to a new location. Come into my office. Would you like some coffee?”

“No, thank you,” she said.

“Don’t sit there,” I said, as she looked down at the sofa and Bodger looked up at her. “You’ll get cat hair on your skirt.”

She was wearing a three-quarter-length black leather coat, narrow at the waist, flared at the hip, and an above-the-knee black skirt. Her patent leather lace-up boots, also black, had long, pointy toes and three-inch stiletto heels. I placed a straight-backed chair in front of my desk, held it for her as she sat down. She crossed her legs with a whisper of nylon. She had very nice knees.

“You’re sure you wouldn’t like a cup of coffee?” I asked again, as she unfastened her coat, revealing, I couldn’t help but notice, a very impressive superstructure.

“I’m sure, thank you,” she said.

I went around my desk and sat down. “So, how can I help you, Miss …?”

“Waverley,” she said in her scratchy voice. “Anna Waverley. And it’s missus. Or at least it will be until my divorce becomes final.”

“Miz, then,” I said.

She smiled. She had a very nice smile, revealing near-perfect teeth, except for one slightly crooked upper incisor, to go with the nice knees and impressive superstructure. Her complexion was clear and smooth, no telltale crow’s feet around her eyes and mouth. I revised her age downwards half a decade, and wondered why she wore her hair and dressed in a style that made her look older.

“In any event,” she said. “I got the house in Point Grey, the condo in Whistler, and the boat, which I’d like to sell. I don’t see any reason why I should pay a broker’s commission, so I thought I’d sell it privately, which is why I came you. I need photographs to send to prospective buyers. I tried to do it myself with my little digital camera, but I didn’t like the way they turned out.”

“Okay. That —”

“Except it has to be done right way. This evening, if at all possible. I’ve already lined up a potential buyer I’d like to email the photos to, but he’s leaving for Hawaii first thing in the morning.”

“That shouldn’t be a problem,” I said. We’d recently purchased an almost-new Nikon digital SLR that was compatible with all our older Nikon gear, lenses and flashes and such. “What’s the name of the boat?” I asked. “And where is it?”

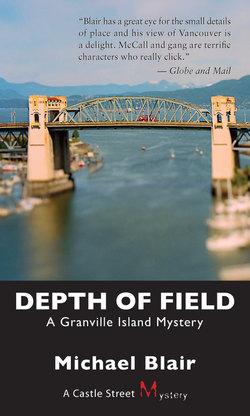

“It’s called Wonderlust — with an ‘O’ — and it’s at the Broker’s Bay Marina at the west end of Granville Island.”

“I know the marina,” I said, adding, “I live on Granville Island.”

“Oh, do you?” she said. “How convenient. Will you be doing it yourself, then?”

“Yes, probably,” I said. No sacrifice was too great.

“Would eight o’clock be all right?” Ms. Waverley said. “I could meet you there.”

“That sounds fine,” I said.

“I really appreciate you doing this on such short notice, Mr. McCall.” She opened her purse and took out a plain white business envelope, from which she removed a pair of keys with a paper tag and a wad of fifty-dollar bills. “I wasn’t sure how much you would charge. I hope you don’t mind cash.”

“Not at all,” I said. “But it isn’t necessary to pay in advance. We’ll invoice you.” I took our standard work order form out of my desk drawer.

“If you don’t mind,” Ms. Waverley said, “I’d prefer to pay in cash. It leaves less of a paper trail.” She smiled her very nice smile. “You know how it is with divorce.”

“I do,” I said. I slid the work order form back into the desk drawer.

After we’d agreed on an amount, to which she insisted on adding another fifty — “For the inconvenience,” she said — she returned the balance to the envelope, tucked it into her purse, and stood. “I’ll see you this evening at eight, then,” she said, holding out her hand.

I stood and took her hand. It was warm and strong, and ever so slightly work-roughened, perhaps by a hobby; I couldn’t imagine her doing manual labour. “Where can I reach you if I, um, need to reach you?”

“My cellphone number is on the key tag.” She indicated the keys on the desk. “In case I’m running late, you can let yourself aboard.”

I walked her out into the studio. She jumped a little as the stairwell door opened and Bobbi Brooks, my business partner, came into the studio. Bobbi’s eyebrows went up as Ms. Waverley went into the elevator.

“I’ll see you at eight,” Ms. Waverley said. The elevator door rattled shut on her.

“Who was that?” Bobbi asked, as she followed me into the office.

“A new client,” I said.

“How lucky for you,” she said.

“Indeed,” I said.

“Her hair wasn’t real, though.” She sat down on the sofa next to Bodger, who grunted softly as she picked him up and cuddled him in her lap. “Or her boobs, probably,” she added.

“Could’ve fooled me,” I said.

“Not exactly a challenge. What did she want?” Bodger rumbled contentedly as Bobbi stroked his ears and I explained the job. When I was done, she said, “Not a problem. I’ve got nothing on till later this evening.”

“Um,” I said. “I thought I’d handle it.”

She sighed. “Aren’t you supposed to be meeting what’s-his-name about his catalogue shoot?”

“What’s-his-name” was the ex-Honourable Walter P. Moffat, former Member of Parliament for Vancouver Centre, the riding that encompassed downtown Vancouver and Granville Island. Wally the One-Term Wonder, as the media had dubbed him after he’d been roundly trounced in the most recent exercise in democratic futility, was a pal of Mary-Alice, my sister and our new junior partner, and her husband, Dr. David Paul. Moffat had contacted us through Mary-Alice about producing a catalogue of his art collection, which he evidently intended to send on tour to raise money for his wife’s charitable foundation, something to do with children. However, first thing that morning a man named Woody Getz, who’d said he was Mr. Moffat’s manager, had called to say that something had come up and Mr. Moffat couldn’t make it.

“How lucky for you,” Bobbi said again, when I told her.

“Yes, indeed.” She smiled. “Here, deposit this someplace safe,” I said, and handed her the cash Ms. Waverley had given me.

Cradling Bodger, she lifted her backside off the sofa and straight-armed the money into a front pocket of her jeans. Safe enough, I supposed. I certainly wouldn’t have tried to take it away from her. While Bobbi wasn’t what you’d call strapping — strapping implied, to me at least, a certain amount of, well, upper-body development and Bobbi was, truth be told, almost as flat as a boy — years of schlepping heavy photographic equipment around had made her as strong as many a man her size, stronger than some. Moreover, she had recently begun to study some form of martial art.

“Moffat hasn’t changed his mind about the catalogue, has he?” she asked worriedly.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I hope not.” Neither of us had any idea what type of art Mr. Moffat collected — it could be dryer lint and chewing gum collages for all we cared — but business was a bit slow and we needed the work. “His manager just said he couldn’t make it tonight, nothing about rescheduling.”

The phone on my desk warbled. I pressed the speakerphone button. “Tom McCall,” I said, just to be reassuring.

“Tell me it isn’t so,” my sister Mary-Alice said.

“Okay,” I said. “It isn’t so.”

I could hear car horns in the background. She was calling on her cellphone, likely stuck in traffic on the Lions Gate Bridge. She normally didn’t come in until after the worst of the morning rush hour was over, and usually left before the worst began. The unseasonable fog had thrown rush hour off schedule, I supposed, without much sympathy.

“You don’t know what I’m talking about, do you?” Mary-Alice said, in her best schoolmarm voice.

“That’s right.” I assumed she was referring to the cancellation of the appointment with the ex-Honourable Walter P. Moffat. “But whatever it is, it isn’t my fault.”

An exasperated sigh hissed from the phone speaker. “I just got off the phone with Jeanie Stone.” Jeanie Stone was vice president of the British Columbia Association of Female Forestry Workers, the BCAFFW, for short.

“Oh-oh,” Bobbi said under her breath.

“Tell me you didn’t let her talk you into doing a nude calendar,” Mary-Alice said.

“Okay. I didn’t let her talk me into doing a nude calendar.”

“Well, she seems to think she did,” Mary-Alice said.

“Actually,” I said, “she didn’t have to.” Bobbi groaned. I glared at her across the desk. “Anyway, they won’t be nude,” I said. “Not really. It’s just pin-up girl stuff. With axes and chainsaws and logging machinery covering the important bits.”

There was a momentary and very pregnant silence, followed by, “Oh, for god’s sake, Tom.”

“Look, Mary-Alice. I know it’s lame, but —”

“Lame? It’s bloody crippled. Ever since those damned women in England started it, it’s been done to death by everyone from senior ladies’ knitting circles to female hockey players.”

“Relax, Mary-Alice,” I said. “It’s for a good cause, remember.”

All proceeds from sales of the calendar were going to the Stanley Park restoration fund; on December 15, 2006, the one-thousand-acre, densely forested park had been savaged by a freak windstorm that had destroyed as many as ten thousand trees, leaving gaping wounds that would take decades to heal.

“Anyway,” I added, “Jeanie’s the client, isn’t she? If she and the other members of her association want to do a pin-up calendar, who are we to argue?” Before Mary-Alice could reply, the phone bleeped, indicating another call. “Hang on, M-A.” I pressed the flash button before Mary-Alice could object. “Tom McCall,” I said.

“Tom,” another female voice said. “It’s Jeanie Stone.”

“Hi, Jeanie,” I said.

“Tom, you guys want this job or not?” She was also calling on a cellphone, maybe from the middle of the woods, if the poor quality of the connection was any indication.

“Oh-oh,” Bobbi said again, even more under her breath.

“Yes, Jeanie,” I said. “We want the job.”

“Then maybe you could get your sister off my case.”

“She’s just thinking about what’s best for your organization’s image, Jeanie,” I said.

“What she thinks is best,” Jeanie said. “Look, I get that she doesn’t like our idea for the calendar, and maybe she’s right that it isn’t all that original, but it’s our damned calendar, Tom. If we wanna do it in our skivvies, we’ll bloody well do it in our skivvies. Or stark effing naked, for that matter. You guys aren’t the only photographers in town, you know.”

“I know, Jeanie, but —”

“Tom, I gotta go,” Jeanie interrupted. “I’ll come by the studio about seven, seven-thirty this evening. We’ll work it out over a beer or two.” The line went dead.

“Don’t worry about it,” Bobbi said. “She won’t fire us. She likes you.”

“She does?”

“God knows why.” She pointed a finger at the phone. “Mary-Alice.”

I pressed the flash button to switch back to Mary-Alice’s call. “M-A? You still there?”

“Where the hell else would I be? The traffic hasn’t moved a goddamned inch since you put me on hold. This fucking fog. Whoever heard of fog in June?” I heard the bleat of her little Beamer’s horn. Mary-Alice wasn’t the most impatient person on the lower mainland, but she was a close third. “Who were you talking to? Jeanie, right? God, men,” she added disgustedly. “You just want to see her naked, don’t you?” She then became the second person inside of a minute to hang up on me without letting me get a word in.

My fancy ergonomic chair wobbled and creaked as I slumped back with a sigh. The chair had been a parting gift from my co-workers at the Vancouver Sun when I’d left almost ten years before to start my own business, and it was showing its age. I knew how it felt, if I may be permitted to anthropomorphize.

“Do you want to see Jeanie naked?” Bobbi asked.

“What? No, of course not.”

“Why not? She’s very attractive. For a lumberjack.”

“She’s not a lumberjack.”

“Lumberjill, then.”

“She’s a ‘forestry worker.’ She drives some kind of big machine that bites trees off at the roots.” Bobbi was right, though: Jeanie was attractive, very much so, in a fierce and brawny kind of way, and I thought she’d make a very interesting study in black and white, clothed or not. I just didn’t want to arm-wrestle her.

“If you want, I’ll talk to her,” Bobbi said. “So you can go shoot Ms. Phoney Boobs’s boat.”

I shook my head. “I’d better do it,” I said. “Mary-Alice has really got Jeanie’s feathers in an uproar. Would you mind doing the Waverley job?”

“Sure,” she said with a shrug. “No problem.”

“Thanks. All right, let’s get to work. We’ve still got a lot of packing to do before the movers come on Saturday.”

After nine years in the Davie Street studio we were moving to a storefront studio on Granville Island in False Creek, the narrow inlet that separates most of Vancouver from the West End and the downtown core. I lived in Sea Village, a small community of floating homes moored two deep along the quay between the Granville Island Hotel and the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design. Granville Island was the former industrial heart of Vancouver, converted in the early seventies by the federal government to a trendy arts, recreation, shopping, and tourist area. It was still managed, with surprising competence, by the feds through the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The move was Mary-Alice’s idea. I wasn’t quite sure yet that I liked it.

I stood up. Bobbi didn’t move. I sat down again. “What’s the matter?” I asked. “Need I remind you that you thought relocating to Granville Island was a good idea?”

“That’s not it,” she said.

“So what’s bothering you?”

“It’s Greg.”

Oh-oh, I thought. Greg was Detective Sergeant Gregory Matthias of the Vancouver PD Major Case Squad, Homicide Division. Bobbi and he had been seeing each other since they’d met the previous fall, during his investigation into the death of the man whose body I’d found on the roof deck of my house the morning after my fortieth birthday party. Had it become serious between them, I wondered, while I wasn’t looking?

“What about him?” I asked cautiously. I tried to keep things between Bobbi and me strictly professional, generally with only moderate success, when I was successful at all.

“I think we’ve broken up,” she said.

“What do you mean, you think you’ve broken up? Don’t you know?”

“No.” She shook her head, rather too vigorously, I thought. Her long, brown ponytail swished, like a horse swatting at flies.

The situation wasn’t one with which I was familiar. Typically, when I broke up with someone, it was made abundantly clear, in no uncertain terms, that the party in question never wanted to see me again, ever. Linda, my former spouse, had hired lawyers to make her point. So far, to the best of my knowledge, none had hired a hit man. So far …

“It was tough enough growing up with a cop,” Bobbi said. Her father had retired a few months earlier from the Richmond RCMP detachment. “I thought dating one would be easier, but …” She shrugged.

I looked at her. Her eyes were dry and slightly bloodshot, and the corners of her mouth drooped. When she put her heart into it, she had a megawatt smile, but I’d seen far too little of it lately. Now I knew why. “Does Greg know?” I asked.

“I think so,” she said. “I’m not sure. We’re having a late dinner to work it out.”

“I’m really sorry, Bobbi,” I said. “If there’s anything I can do to, you know, well, help …”

She stared at me in mock horror, as if my offer of aid in matters of the heart was akin to Willy Picton offering to cook barbecue. Then she smiled, releasing a couple of kilowatts. “It’s no big deal, Tom. Win some, lose some. Thanks for caring, though.”

“You’re welcome,” I said, thinking that maybe it was a bigger deal than she let on.

We got to work. Half an hour later, Mary-Alice arrived.

Mary-Alice was younger than me by slightly less than two years, but had always treated me as though I were her slightly slow younger brother. She had become a partner in January, buying fifteen percent and taking over the marketing and administrative aspects of the business, leaving Bobbi and me free to concentrate on the photographic and creative end of things. I was still the majority shareholder — Bobbi owned twenty-five percent — and remained more or less in charge, but I had gone along with Mary-Alice’s proposal to relocate to Granville Island. Digital photography was putting a lot of traditional commercial photographers out of business, or at least forcing them to adapt. The new digs, which along with a studio space and a small darkroom, included a gallery and retail area, would allow us to tap the consumer and tourist trade, while still maintaining our commercial business. Bobbi was dead keen, as was D. Wayne Fowler, our lab guy, who was equally at home with traditional and digital photography, not to mention the computers, and was a fair hand with a camera himself. As I said, I wasn’t sure …

Especially considering the amount of junk we had accumulated over the years. A good deal of it went down the freight elevator and straight into the rented Dumpster or recycling bins, and we’d actually managed to get a few bucks for the old Wing-Lynch film and transparency processor, as well as for some of the redundant darkroom equipment, which had already been carted away by the buyers, but there was nevertheless a daunting amount of photographic and office equipment, furniture, file and storage cabinets, and miscellaneous bits and pieces to pack up before Saturday. By two o’clock, despite the best efforts of the four of us, we seemed hardly to have made a dent, so we took a break.

“Whose bright idea was this, anyway?” Mary-Alice wondered aloud as she collapsed onto the sofa in my office and raked webs of dust out of her pale blonde hair.

“YOURS!” Bobbi, Wayne, and I shouted in unison.

“Why the hell didn’t you try to talk me out of it?”

“We did,” I said. Wayne handed out cans of Coke.

“You should’ve tried harder,” Mary-Alice said, nodding thanks. “You could have at least told me how much rubbish you had hidden away.”

“I didn’t realize myself how much there was,” I said.

“I hope everything f-fits in the n-new place,” Wayne said.

We put in another couple of hours, then ordered pizza, courtesy of Ms. Anna Waverley. Mary-Alice had given me a hard time about accepting a cash client, but I told her we did a fair amount of cash business and, yes, we declared it. I wasn’t sure she believed me. Any more than she believed me when I told her I would try my best to talk Jeanie Stone out of doing a pin-up calendar. Mary-Alice subscribed to the philosophy that the customer — or the boss — was never right.

Bobbi hung around the studio with me for a while after Mary-Alice and Wayne left. The place looked as though a herd of hyperactive rhinos had stampeded through it — and back again. Bodger wouldn’t come out from under the sofa, even for Bobbi.

“You still think this was a good idea?” I asked her.

“I’ll miss this place,” she said. “But, yeah, I think the move is a good thing. We were getting in a rut.”

“I liked my rut,” I said. “It was familiar, comfortable. It took me a long time to break it in.” Truth be told, though, I had been feeling a vague sense of discontent of late, as if things weren’t turning out quite the way I’d expected them to when I’d started the business. Nothing I could put my finger on, just a nebulous feeling that a change was in order — just not this one.

“What’s the news from Hilly?” Bobbi asked.

“I got a postcard yesterday,” I said. Hilly — short for Hillary — was my soon-to-turn fifteen-year-old daughter. She’d been in Australia since the fall, with her mother and her stepfather Jack, the Fat Food King of Southern Ontario. She liked it Down Under well enough, but was eager to get back home to Toronto and her friends. “She says hi.”

“Say hi back.”

“Will do,” I said.

After a short silence, she said, “How’s Reeny doing?”

“All right,” I replied. “I guess.”

“She’s still in France, then?”

“Germany,” I said.

Irene “Reeny” Lindsey was an actress I’d been seeing since the previous September. Except that I hadn’t been seeing much of her in recent months. Reeny was the co-star of Star Crossed, a syndicated sword-and-sex sci-fi series in which she played Virgin, a time-travelling bounty hunter who’d come to present-day Earth with her companion and senior bounty hunter, Star, to track down evil shape-shifting alien outlaws and bring them to justice, generally shedding most of their clothing along the way. It was almost painfully cheesy, but it had earned Reeny and her co-star Richenda “Ricky” Rice a huge cult following, not to mention quite a few dollars. The third season was being shot in Germany.

“Uh, look at the time,” I said. “You’d better saddle up.”

“Right,” Bobbi said.

I helped her lug her gear down to the van, although she didn’t really need my help, then went back upstairs, got a Granville Island Lager out of the film fridge, another thing digital photography had made more or less obsolete, and put my feet up to await the arrival of Jeanie Stone. I hoped she wouldn’t be too put off by the mess — and that she brought more beer.