Читать книгу REFLECTION - Michael Blekhman - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

IV

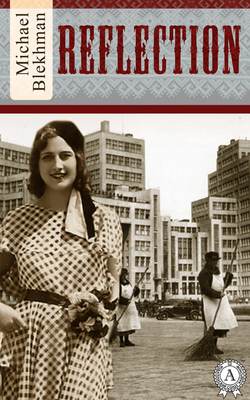

ОглавлениеMary was beautiful, with thick dark hair, huge, slightly protruding eyes, and a touch of condescension in her smile.

At the age of sixteen, she married Zinovi Stolberg, an energetic, intelligent and enterprising young man. Three years later, in 1929, she gave birth to Klara and left her husband because he annoyed her with his opinions. Not his opinions as such since she never listened to what he said anyways but, rather, with his having the gall to express opinions.

Of course, Zinovi was Zinovi just as much as Aaron was Arkadi. His real name was Zalman, so Klara was in reality Klara Zalmanovna instead of Clarissa Zinovievna, as she started introducing herself later in life. Zinovi had planned to call her Elena, but having opinions turned out to be a bad idea for him. Maria ended up following her own rule that a son should be given his grandfather’s name, while a daughter should be named after her grandmother.

After the divorce and before the war began, Zinovi sometimes saw Klara but it happened so rarely that she felt she almost never met him at all.

In Kharkov, which was the first Ukrainian capital city after the revolution, Maria entered an engineering program and became its best student. That was no surprise because a person who can come out a winner from a struggle with the Dnieper will not be defeated by anything that can happen on even the most challenging stretch of land.

Arguing with her was impossible or, rather, it was completely useless. Her logic and her way of constructing an argument were more than ironclad, they were made of some yet-to-be-discovered refractory substance. Maria’s classmates, who were mostly Civil War veterans, used to say she had a male brain. Still, she was a woman. With a braid encircling her head, huge eyes, and the capacity to cross any river, no matter how challenging the task might be to any self-proclaimed hero.

Every morning, Maria would walk from her apartment in Pushkin Entry to Sumskaya Street, smiling at the soaring golden Engineering House, and the bright grey Gosprom sky-scraper, and the rising building of the Ukrainian Government in the endless – as endless as her entire life – Dzerzhinsky Square. Her life was only about to begin, and the world’s best monument to the poet Taras Shevchenko wasn’t there yet, just like the Glass Fountain wasn’t there, and she had no way of knowing that it was going to resemble her chiffon scarf.

Her heels clicked against the obedient paving stone and the timid asphalt, in her brief-case she had her homework, which was the best in her cohort, and in her blueprint tube she carried the best drawings of anybody in her program. The Sumskaya Street, endless in its regal flow, moved past her towards the tsarist buildings, the Salamander House, the imposing bank building, the Pushkin Square, and the festive Ukrainian theater. Then, it joined the Nikolaevskaya Square, where buildings designed before the war by the famous Professor Beketov winked at Maria with their crystal-clear windows. Lower down, she could see a tranquil grey no-frills building constructed as recently as 1925.

On weekends, Maria would leave Nikolaevskaya Square and walk down the prideful Pushkin Street, which at that time one couldn’t even imagine crossed by trams or railways. She would pass by the churches that made the street look the wife of a merchant guild’s honorary member. Then on to the buildings designed by the famous architect Beketov, which reminded her of a string of Christmas lights or October fireworks and which made the street look as aristocratic as it so richly deserved. She would return to her own Pushkin Entry to prepare for class, read, draw, and wield her slide rule.

And, of course, to come out to the balcony with Klara to stare into the skies that had blessed them with the miracle of their endlessly happy lives.