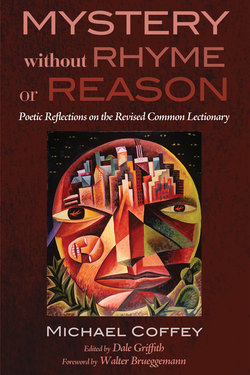

Читать книгу Mystery Without Rhyme or Reason - Michael Coffey - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеI began this project as a New Year’s resolution. I decided to begin writing a weekly reflection on the lectionary texts used in worship by the majority of churches. I intended to do this for one year. The year came and went and I realized that reflecting poetically on the lectionary texts each week had become a part of my regular spiritual and homiletical discipline. So I kept writing each week, and before I knew it I was completing a set of writings on most Sundays and holy days for the whole three-year Revised Common Lectionary.

It may not seem obvious as first, but this collection of poems is a work of theology. It is obviously not a work of systematic theology, nor is it an exercise in expressing the orthodox tradition of the church through poetry. You might summarize what my own theological leanings and convictions are from these pieces, looking for patterns, common vocabulary, and emphases. But it is not anything close to a summa theologica; in some ways the intention of these writings is just the opposite. It is at best a poetica theologica.

I have become convinced that the Western theological tradition, as wonderful and insightful as it has been, became too enamored of rational and systematic thought as the sole means of accessing the truth of God. Somewhere along the way, Christians, especially of the academic and clerical type, assumed that the truth of God and our lives was mostly, or even only, captured through rational, intellectual, systematic, and dogmatic writings. All the while, of course, the West continued to produce great visual, written, and musical art, all of which expressed essential truths about God and Christian life, but these expressions of faith and theology have always been relegated a second or third level of importance and truth when it comes to theology.

My conviction is the church would be served well by more poetry, as well as more art and more artists. Walter Brueggemann’s book Finally Comes the Poet speaks of Isaiah as the prophetic poet who brings poetic truth to a prose-flattened world. His work has greatly influenced my understanding of poetry as a vehicle of theological truth and encounter, seen wonderfully in Isaiah and Jeremiah and Jesus and so much of the great biblical tradition, not to mention the best of the liturgical and ritual traditions of the church. The key point I derive from Brueggemann’s phrase here is that poetic truth is not flat. It is not easily resolved into precise statements. It is irreducible and therefore engages the reader, much like so many biblical texts, in a conversation about the truth of God and the world and ourselves, a conversation that is open-ended and never finished.

This, of course, is precisely why poetic expressions of faith and theology are so suited to the task. The One of whom we speak and to whom we speak and listen is not flat, not resolvable, and is irreducible. Therefore, we cannot speak of God in such a way that misleads us into assuming we have captured and controlled God, and so we are finished with God. Poetry, much like humor, is never served well by being explained, but only by being encountered and experienced and confronted by and enjoyed. The same could be said of God.

The word “mystery” is so useful here because it leads us to encounter the holy as something knowable but never fully known or explained. Mystery is something to be enjoyed and experienced, but not explained, at least not in any final, dogmatic way. It is the truth of things that cannot be approached directly, but only sideways, tangentially, with peripheral vision at best.

These poems are, I hope, a way of enjoying the mystery and wrestling with it a bit, and it with us. It is not an attempt to use reason to capture God, but to move beyond reason as the primary category of truth. It is poetry without rhyme or reason, and therefore, maybe in the smallest and most humbling of ways, worthy of its subject.

A note on names for liturgical days: For Sundays outside of particular seasons like Advent or Lent, I am using the designations found in Evangelical Lutheran Worship. These days are called, for example, “Lectionary 23 A,” and correspond to the “Ordinary” days as named in the Roman Catholic and other lectionaries. The number scheme corresponds to the “Proper” designation by subtracting five. For example, “Lectionary 23 A” corresponds to “Proper 18 A.”