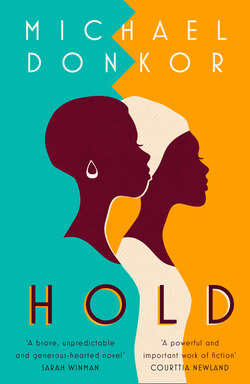

Читать книгу Hold - Michael Donkor - Страница 17

8

ОглавлениеThe following afternoon Belinda asked Nana for the kitchen scales. She wasn’t frightened when informed they were ‘electronic’ while Nana tied her into an apron. The small glass shelf presented to her was mean-faced, like the calculator from SS2. Belinda squared her shoulders at it.

‘Me pa wo kyew, leave me please to shape and fry the bofruit, and you please ask your Amma to join us for a taste of these in perhaps half an hour. In that upstairs living room, or whatever you have call it before. For a change? And I will prepare the coffee in the special pushing-in thing I’ve seen she uses.’

Belinda wondered if their hopeful smiles matched. Perhaps that possibility kept the smile there long after Nana had gone, and Belinda was alone, tapping eggs against the bowl, licking swipes through leftover batter, dropping sweet dough into blipping oil. With the cooking done, the grin remained as she arranged the grainy globes and fanned napkins. Her hands slipped into the breakfast tray’s rounded slots, a feeling that reminded her of teaching Mary to carry properly and not to balance food on the head any longer. The grin stayed as she transported the doughnuts and coffee, each step an effort against the jangling of porcelain. Her cheeks contracted as she saw Amma.

Amma’s head faced the ceiling, ignoring the crouching mother in front of her who struggled up to full height. Amma’s skyward expression was of concentration, set on the plaster vines weaving the whiteness above.

Belinda pressed her lips together, then slowly relaxed them out and breathed. ‘Shouldn’t, shouldn’t be surprise to you? You got them in all the rooms. But me, I never saw anything like these patterns and designs and things on the ceilings before. Is very pretty, but I’m almost thinking how did someone come up with the idea to put them up there? Who was the first one to do it and why?’

‘You won’t help your sister, eh? She has prepared for you this special, and so –’

‘Belinda, totally. Yeah. Thank you.’ Amma took the tray from Belinda’s strict grip, lowering it to the coffee table. Belinda thought the girl smelled so clean and flowery, despite all the dirty shades of black and mud and grey she wore. ‘This is very kind – thanks – and there’s no need to be so utterly patronising, Mum.’

‘I’m only trying to get you to –’

‘We don’t need to have a discussion about everything.’

‘OK, Amma. That’s OK. No one is trying to be difficult here.’

‘I’m not trying to be anything. It appears that I just am.’

‘No. No. Belinda has prepared something for you to enjoy. That is the thing for now. To enjoy. Do that, eh?’

The stretched final note made Belinda play with her earlobes, as if touches to their softness would help. Amma rolled on the armchair towards the food. She rested her elbows limply on legs splayed like a man’s, then pulled herself forward to press the cafetière’s plunger.

‘I don’t suppose you want some, Be?’

‘No. I mean, no thank you. Is very strong for me, even if I know you like it as such.’ Amma’s forehead moved, dipped slightly. ‘I hope you like it well.’

‘Sure I will.’ Amma splashed in milk, eased back and seemed to wait for the next move, next sentence. In its absence, Amma shook her head and sucked shiny wetness off her little finger. She reached out and bit a bofruit. Belinda almost felt sorry for the doughnut collapsing under the assault. Although, of course, she felt sorrier for herself.

The decoration of this upstairs room, Belinda thought, might have been the reason why the conversation between the two standing and one sitting snagged. The second living room seemed silly, not for living in at all. Belinda had only been allowed to a museum once: a compulsory Cultural History trip Mother saved hard for. This was another museum. Kente scarves meant for celebrations were flattened behind glass, rainbowing walls. Alongside them, huge paintings of bloody sunsets and kola trees, women loaded with pots, curved elders relying on long sticks for support. But the black figures in the pictures were wiry and stretched, and the backgrounds painted in something smoky; these were images of a place so much dreamier than Belinda’s recollection of that world.

Rather than books, the bookcases were for ornaments and framed papers. One set of shelves presented several documents, bordered with complicated black swirls. Each was marked with shiny holographic stamps, like sweet wrappers. Most had Amma’s details written in important letters, the middle name Danquah misspelt in different ways. On remaining shelves, jutting their arms, rows of akuaba stood to attention. The fertility dolls’ inflamed heads and pinched features always seemed odd to Belinda; ugliness for objects meant to bring a pretty, fat baby into the world seemed wrong.

‘You see how Belinda is fascinated by our traditional things? You enjoy my collection? The dolls?’

‘Is a very big one … very unusual to have.’

‘They’re, er, very – very surly, aren’t they, Ma? You almost want to pick up the little darlings and ask them what their bloody beef is,’ Amma said, mouth full.

‘Bloody beef? What is a bloody beef to do with these, Amma?’

But Nana interjected, ‘I suppose how the whites they sometime collect these stamps, buttons and whatnot, this is my version. I told myself every time I went back to our homeland I will collect one or two to bring back, trying to find something nice that will complement the ones I already have, you know? First it was a bit for juju as well, I cannot deny that.’ Nana flexed her golden fingers and rearranged some of her loose, greying curls. ‘Even after all these years of collecting and hoping and praying, when my little girl actually came, I still kept getting more, because I … they give me a sense of protection. Or something along lines like that. You get me?’

‘Hanging on to the past, Mater. Get rid, non? I’m sure Oxfam would be delighted to receive a job lot of these lovelies – and what a beautiful symmetry there’d be: African gems saving African lives. Et cetera.’

‘A big-time joker. That’s good for you. Congrats to the comedienne. If your father wasn’t in his work, I’m sure he will be here with you, also laughing it up and having a great fun. But when I talk of that time before you? Me, I can’t find any funny at all. A hard, hard time to wait for you, Amma – my very, very hardest time.’

Her hand waved Amma’s reply aside. Nana bent down for a napkin and nestled it and a doughnut in her palm. Belinda wondered if she should have added a dash of lemon juice, to sharpen the taste.

Nana seemed amused by something. ‘Maybe the third or fourth time when I’m starting to gather all the dolls, I go home for a visit; my mother was unwell deep inside her back. Complaining and coming up with such horrible ideas: how the spine is rotten off and will soon fall out. Adjei! Can you imagine this nastiness? Anyway, when I was staying in the compound that time, everyone was joking of this kwadwo besia who had passed through the village – eh, Belinda, how can we explain kwadwo besia for her?’

Belinda blinked several times, tugged the striped strap of her apron and then shrugged.

‘Is like one of those … sissies. Those, erm, Lily Savage, Edna Everage. Amma; I used to ask you if Margarita Pracatan is one? Anyway, anyway: they told me he carried his own akuaba on his back as though he is a real woman, wanting a child like I. And I thought; no, they are lying about this one, it cannot be like that, you can’t take the mimicking so far. But on one afternoon, I saw him! Is like when you see a Father Christmas for the first time in the shopping centre. He was knocking on someone’s door to beg for change. Adjei, I never knew anything such as this, Belinda. More than six feet and with a dress for a nightclub with sparkles, only covering his buttocks and let you see all of the big legs – and his hair? A wig like he has fetched it from the roadside. Trampled. And a massive one of these dolls strapped to his back in our normal way as if he is a normal. We laughed! We. Laughed. My mum had been bedridden for weeks and moaning moaning, suddenly she is laughing so much we fear that she would urinate! All the little ones came with sticks and bad pawpaws to throw at the him–her, and as he is running away, the kwadwo besia cannot even get out quickly enough because he can’t walk in the women’s shoes!’

Nana stopped to chomp and wipe away a pretend tear of laughter. Belinda wished that Amma hadn’t turned to the ceiling again, with her jaw even more fixed. Belinda wished Amma wasn’t closing her eyes, making her face so peaceful and breathing so steady when Belinda sensed that those were not the girl’s actual feelings.

‘I only thought kwadwo besia was on the television. For comedy. Not in real life. It must be very great to encounter one in the flesh,’ Belinda tried.

‘And why you so serious, Miss Otuo? I think that’s one of my favourite tales. Not even gonna do a little smile for me? Tough crowd here, innit?!’

‘Kwadwo be-sia. Kwad-wo be-sia,’ Amma whispered, before adding with force, ‘I’ve got memories of Ghana all of my own.’

‘Yes! Good! Share with your sister Belinda also. Excellent.’ Nana settled into one of the armchairs and invited Belinda to take the other. ‘Seem like you not interested in back home matters. You giving all your excuses not to come at Easter when you could have met Belinda at your Aunty’s fine place – some parts of Kumasi now are so beautiful you even feel as though you are in Los –’

‘I bet you don’t remember this one, Mum.’

‘We are all ears.’

‘I was in Year 2, or something. It might have been your hometown or Dad’s we were going to. And I insisted you gave me the plastic bag with all the money in for the relatives; there was tons of it. So we were, like, walking, and I was being all bossy with the bag and probably trying to show off with the, like, two words of Twi I’d picked up, because showing off was totally my thing back then.’

‘Back then?!’

‘We were getting closer to the actual village and I saw all these orange clay or mud or whatever houses next to each other. They had these slits for doors that I thought were really small, and I said to you something, like, about how Ghana was only for skinny people or something equally insensitive, I’m sure …’

Belinda watched Amma stretch the ripped thumb-holes in her jumper.

‘We kept walking, and then this massive queue, like, appeared? Everyone in it was all, like, jostley and impatient. And facing the queue – sort of like everyone had come to see him – there was this little boy and he was crying. I think he was probably about four or five because I wondered if we could be friends. That’s when I noticed his hands and feet. They were tied up. And the dude at the front of the queue, like, whipped off his, his, flip-flop, his – challewate.’

‘We pronounce as cha-la-watt –’

‘And went completely psycho all over the little boy. Laying into him with it. Even when he screamed and shit –’

‘Amma –’

‘And then, like, yeah, I got that everyone else in the line was getting ready to do the same: they were all bending down to take off the one shoe. And we walked past and made small talk when all the uncles arrived, and they said nice things until you handed them cash.’

‘Amma.’

‘So that’s probably the thing I remember most about Ghana. Yeah.’

‘I don’t think that’s a very good story.’

‘No?’

‘Is it necessary, Amma? Eh?’

‘For, for the bofruit, I used a recipe I have known since I was a small girl. My trick is adding the vanilla. Is expensive, that’s why people they don’t like to add, but if you have only one pod, and you use only a few of the small small beans in it, is sufficient. It will give plenty of flavour. In your cupboards I noticed you have many vanillas. So. No problem.’

Outside, the still, white sky seemed to be the sigh Amma released. ‘It doesn’t matter. Really. It doesn’t. None of it does.’

The words travelled lightly from her, along with other, more muttered phrases. Amma stood, walked out, and Belinda’s hands flapped, forgetting how to hide in pockets. Nana’s head was bowed, and she let herself hang like that for a while, as if dragged by the small pendant at her neck, and Belinda reassured herself by looking at the exposed, biscuit-coloured nape, knowing how soft it must be to touch. Belinda wondered if Nana had ever found somewhere quiet and hidden to cry, like she had done in the early days at Aunty and Uncle’s. Crouching in the tool shed, with an oily rag in her mouth and the tears unable to come out was the worst one, on an airless Wednesday. She had ironed and stored Uncle’s handkerchiefs for three hours without stopping. The instructions were that they needed to be folded identically. After attending to at least fifty, it came on her: a falling, falling feeling that had her scuttling around until she found safety, away, breathing fast amongst spanners and wrenches and nails.

It was difficult for Belinda to remember exactly what had brought on that sensation. If it was just the grinding nature of the work. Or a fear that she always had in those early days in Daban, that her dirty, village hands might leave a grimy trace or mark on the fine fabrics she was being asked to handle. Or fear that Aunty would ask her a question about Mother’s life and that Aunty’s clipped voice might make Belinda say too much. Or if the horrible feeling was prompted by the loneliness of being somewhere new, despite the small girl who shadowed her for most of the day. What Belinda could remember clearly was the pressure of the cloth in her mouth; the silencing, muffling force of the fabric on the back of her throat. Painful but comforting at the same time.

Belinda wanted to ask Nana what she should do next but was interrupted by Amma’s return to the room – a swish of loosened plaits, sweep of sleeves, stomp of boots.

‘These are fucking delicious, Be.’

Amma collected three more bofruit and swept away. Belinda’s stirring hands stilled.