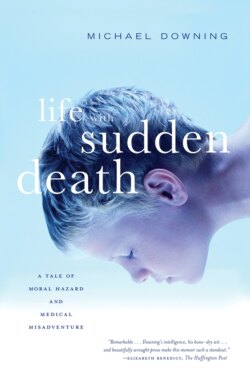

Читать книгу Life with Sudden Death - Michael Downing - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4. Negative Capability

When my brother Joe was in sixth grade, he started wearing ankle weights. He said they were designed to improve your basketball skills. We were both on the St. Teresa’s team in the Catholic Youth Center’s parish league. I sat on the bench and Joe played, and our team usually lost. I was in fourth grade. This was the year St. Mary’s parish started using their second string by the middle of the first half in games against us. Kids my age were able to hold a lead against kids Joe’s age. Our coach, Mr. C., said it was bad sportsmanship. Joe said St. Mary’s was just breaking our spirits, and he admired them for it.

Joe didn’t think Mr. C. had the right killer instincts and blamed him for a lot of our losses. He also blamed a couple on the coach’s son David, who was Joe’s age and just as skinny but had the liability of often losing his glasses and seeing a blur at important moments, like when shooting and passing. David was Joe’s friend and our best scorer, but sport bands didn’t work on his head, for some reason. Joe said if he had a head with a problem like that, he’d use Red Cross adhesive tape, which held firm to eyeglasses but could be removed without ripping your hair out. I’m sure he suggested this to Coach C. Joe was known for making helpful suggestions in the locker room after we lost games. He also started wearing his ankle weights to bed while he listened to staticky broadcasts of Weber State college basketball games on a Rocky Mountain radio station he could pick up after the local Berkshire stations went off the air.

Joe was devoted to basketball. He practiced his layups and bank shots for an hour every day, using the backboard and hoop posted above our tarred-over carport. He wore terrycloth sweatbands on his head and both wrists. For his birthday, he asked for tube socks and extra lead bars for his ankle weights. Whenever he was waiting for me at the barbershop or Dr. F.’s, he’d snag all the free trial-subscription offers for basketball magazines. He used them methodically, so he appeared to be a regular subscriber and became eligible for all the superstar posters they gave away free to paying customers.

Joe figured out how to mount the posters of Wilt Chamberlain and John Havlicek with masking tape on flattened cardboard boxes he collected from the A&P, and he suspended them from the wooden ceiling molding with string all around his half of our bedroom. We weren’t allowed to nail into the wall, except for crucifixes over our beds and a small foot-square mirror for combing our hair in the mornings, which was always off-kilter, like the parts in our hair, because we stuffed the blessed palms from Palm Sunday behind the mirror. Joe’s ability to invent a poster gallery without breaking any rules or wall plaster caught everyone off guard. At dinner, we discussed how this was a prime example of Joe’s bad habit of doing things according to the letter of the law.

My mother must have complained privately to one of the older kids, because somebody taped up four felt banners on my side of the bedroom—two greenish ones from the Ice Capades and two red ones from the Ice Follies from years before I was born. I really didn’t know if the banners were supposed to be revenge against Joe, home decor, or just proof that the older kids had attended big-ticket sporting events in person when our father was alive. Joe said ice shows weren’t real sports, which annoyed me because I had no other memorabilia. After a bitter argument, I threatened to tell my mother his posters were giving me trouble sleeping. Then Joe said maybe he would consider the Capades a semipro sports event, but definitely not the Follies.

In sixth grade, Joe was still constantly acting surprised that our seven older brothers and sisters were no more interested in his basketball career than they were in our piano lessons or paper route. He used to ask me if I’d noticed that neither of our brothers ever wanted to play one-on-one or coach you in calisthenics. Usually he would ask while he was flat on his back and sweating. I was supposed to be timing his leg raises, but I would lose count and he’d get frustrated and warn me that I was showing signs of lacking the discipline to be a sports star. He’d be lying on his back with his ankle-weighted legs in the air. Despite all we’d heard about our brother Jack—he was practically world famous in our family for being a natural athlete—Joe would darkly add, Name one Downing who ever got a varsity letter.

I’d say Jack, in any sport he tried. And maybe Peg, I’d guess, in basketball and softball and swimming. I knew Joe wouldn’t count a girl, but she was my next-best bet because she was four inches taller than Gerard, and stronger and faster. She also had much better natural aim with balls and rocks. I would add Gerard, in debating.

Usually Joe’s legs would be shaking in midair by then, and he’d be panting when he’d say, That’s why they all have letter sweaters and hero jackets, I suppose.

That I suppose was cynical, according to my mother, and I didn’t like it from Joe any more than she did, so I’d estimate his legs had been in the air for only 24 seconds, or something way below his record. Even though he knew I was lying, he’d keep going until his head started to vibrate. I’d spend the rest of the day scouring everybody’s closets and bureau drawers for evidence of athletic prowess to prove Joe wrong, until a housecoat with snaps or a pair of particularly complicated sling-back shoes with buckles caught my eye.

Unlike Joe, I was not eager to have my older brothers coach me. When I was eight, a new kid named Danny moved onto our street and tried to make friends with me. I was interested in him because he was new, and he was my size, and he kept his Red Sox jacket zippered up to his chin, even if you invited him indoors, because he’d always sneaked out of the house wearing his pajama tops instead of a proper shirt. Also, he owned a jump rope, which I coveted. In my house, only the girls got those.

One day, Danny and I got into a fight about something—my father was dead and his father was in Arizona, and figuring out who was worse off occasioned a lot of fights. Neither Danny nor I had ever landed a blow. We both twirled our arms like propellers and threatened to move closer, and then we’d get tired and call it even. But this time, Gerard, who was too old to be playing with us, came out of the house and sat on one of the swings in the backyard and watched our fight. He called us both sissies and yelled, Stop slapping the air. Make a fist.

I did, and Danny stopped whirring and said, I dare you, and he put his hands on his hips and bent toward me. Maybe he double-dared me.

Gerard said, Punch him.

I punched Danny in the head, and he fell down crying. I felt like crying, too, but Gerard said, He took a dive, which I didn’t understand, so I ran away. My hand hurt, but I wouldn’t look at it. I had a terrible feeling that part of Danny’s skull and some of his hair was stuck to my knuckles. That night, I worried that Danny would call the cops or my mother, but he didn’t. He came over the next day with his jacket zippered up and said, I’m sorry.

I wanted to tell him that I liked his jacket, but I was too ashamed to say anything.

Danny said, I’m not a sissy, though.

I said, Neither am I.

And after that we couldn’t figure out how to be friends. Danny and his mother moved away a few months later. I never had another fist-fight. Nobody ever punched me in the head. I did learn how to tie old window cords together to make a jump rope, and my brother Gerard said it was okay as long as I told everybody I was training to become a boxer.

Joe was never accused of being a sissy. The problem with Joe was that he wanted to become good at things. This went against the idea that members of our family could “wing it” in most situations that other people had to prepare for. We used our God-given talents for winging it and devoted practice time to getting better at saving our souls.

Our daily prayer routine was rigorous—morning prayers by yourself on your knees beside your bed; grace before meals; Mass on Sundays, sometimes followed by nighttime Benediction services; Mass on holy days, brothers’ and sisters’ birthdays, every morning in Lent, all during the month of May to honor Mary, every First Friday of the Month to beef up your plenary indulgence account, and First Saturdays as well—though I suspected early on that this was my mother’s personal innovation, sort of like the coach who makes you do fingertip pushups; ejaculations like “Jesus Save Me” or “Blessed be Mary, Mother of God” for a couple of minutes, at least, on the way to and from school every day, and when you were bored and not allowed to work ahead in class; a sign of the cross and another ejaculation or two whenever you heard an ambulance or fire-truck siren; the Rosary after dinner “as a family”; night prayers by your bed, occasionally with a monitor at your door to make sure you weren’t skipping essential beseechments and litanies; and once you were in bed, you received a final dousing with Holy Water—Gatorade for sleeping spiritual athletes—from the wall-mounted font in the upstairs hall. There was also a Holy Water dispenser by the back door, in the kitchen, which Joe dipped into every time he left the house.

This stuff was just normal. But practicing or training or even quitting smoking for sports or musical instruments meant you were missing the whole point of being one of the Downings. Joe was always in danger of becoming a scrupulous fanatic with the wrong priorities, and one of the best things the older kids could do for him was to try to get him to lighten up with jokes about his training regimens.

Joe often tried to convince me that we were at a disadvantage because our dead father was not able to teach us anything useful, but I mostly liked things the way they were. Unlike Joe or our older brothers, and like most of my sisters, I was a natural swimmer. Every summer, about a week after swimming lessons ended at Pontoosuc Lake, I would enter a few events in the Berkshire County Swimming Championships and come in fifth or sixth. In fourth grade, these races were moved from the lake to a new private outdoor pool, but I was still allowed to enter.

By then, my sister Elaine had finished her missionary work in Oklahoma. She was living at home and working as a laboratory technician at St. Luke’s Hospital. She wasn’t a nurse, but she had natural talents in the field, so she was allowed to take my blood at home one night. Maybe I was sick and we were getting a discount on the blood work. More likely, my mother thought Elaine needed practice to keep her new job. I know that Joe was in his bed and told not to watch. He’d seen Elaine practicing with needles on oranges around the house, so he didn’t think I had anything to worry about.

I asked if it would hurt.

Elaine said, You’ll feel a pinprick.

My mother said, You won’t feel anything.

Elaine adjusted the desk lamp so it spotlighted my veins and I couldn’t see her face. She rubbed a cotton ball on my arm and said I should look at the Ice Capades banners. She had a soft voice that made you think she would not end up hurting you.

My mother said, When you’re nervous, Elaine, you make the patient nervous.

She didn’t have a nursing degree, either, but she was always very informed about professional standards.

Elaine said, He has big veins.

My mother said, He’s a real Martin, which was her maiden name. I was pleased. The kids who were more like my father’s relatives had practically no veins.

Elaine jabbed my arm.

I watched the needle draw out brown sludge, and I asked about the unusual color. I didn’t want her to feel bad, but I thought she should know she’d probably tapped into the wrong system.

Elaine said, Blood isn’t red.

I looked to my mother.

She said, That’s enough. He’s just a child.

This made me think it was just for practice.

I never found out what they did with my blood. After they were gone and the room was dark, Joe said, How’d it go?

Okay, I said.

He said, I suppose no one’s ever heard of the school nurse around here.

I especially trusted Elaine because she was the best of the natural swimmers in my family. That summer, she and my mother surprised me by coming to watch me swim in the county championships. I took this as an apology. It was common knowledge that nobody in the family had to attend sporting events for Joe and me.

As usual, I had trained for the big meet by practicing my racing dives for a couple of days and asking some kids at the lake if they knew what time we had to be at the pool. In between my events, when other kids were eating dry Jell-O or taking cold showers, I cheered for kids I knew, especially Barbara Jean. Barbara Jean’s grades and conduct marks were as good as mine from first grade through fourth at Notre Dame grammar school. She was also able to win almost every swimming race she entered. She wore a red-white-and-blue-striped tank suit, like Olympic swimmers, and by fourth grade, no one had beaten her in anything but breaststroke. It was just good luck that breaststroke was my best stroke, so swimming did not interfere with my crush on Barbara Jean.

There were usually between ten and thirty kids entered in every event, but they put all the kids they thought had a real chance in the last heat. I’d finished sixth or seventh in a couple of events before my mother and Elaine showed up, and then I had to swim the breaststroke. I dove in, and after the splashing died down and I’d taken a couple of strokes, I counted how many kids were ahead of me, which cost me a couple of seconds. But I had to keep my head above water for a while to make sure I’d counted everyone. My goal was not to let any more kids pass me. This was my idea of a competitive strategy.

When I finally finished counting, I looked to the end of my lane and saw my sister Elaine. She was small and compact, with short dark hair, and her eyes were almost almonds, making her pretty in a peaceful, Eskimo way. She was the quietest of all my sisters. When I saw her, though, Elaine was bent over at the waist, and she was holding her hair off her face with one hand and using her other hand to make a cup around her mouth. I’d never seen anything like it. I kept my head up for a couple of strokes just to hear what she was saying, and I realized she was screaming at me—Put your head down! Pull! Pull!

I did. I thought Elaine might get in trouble. I’d seen other kids’ parents and older brothers doing this, and my family had explained it was a low-grade form of cheating. Pull harder, Elaine shouted, correctly guessing I wouldn’t remember to keep it up. You’re in fifth place, she yelled, which was really a surprise, unless I’d miscounted.

As I hit the turning wall, Elaine really let me have it. YOU HAVE TO PULL HARDER. MICHAEL! PULL ON EVERY STROKE. FASTER!

I’d never been so excited in my entire life. No one had ever cheered out loud for me. It was a big help. I passed one kid, and Elaine kept yelling, Pull! whenever I popped my head up for a breath of air. I pulled even with two other kids, and I felt my hands slam against the wall. I came in third or second. I don’t remember.

I do remember that an embarrassingly handsome college guy wearing a white-and-green-striped bathing suit and a stopwatch and nothing else told me I was invited to join the county team for a championship meet in Springfield, Massachusetts. His name was Donny. Donny told me that the kid who’d won my event was turning thirteen in a couple of days, and he needed an eleven-year-old “who can really turn it on in the last lap.” Donny had a perfectly even all-over tan. He was reading across columns on a stack of papers he had attached to a silver clipboard. I was watching how the sun gave his reddish brown hair highlights. Donny also thought I could drop my time with better starts and turns.

I was eager to sign on for the whole Donny program. It was the first swimming medal I’d ever won, and though I would go on to win more medals and a few trophies and a varsity letter, I knew right then that I was in danger of becoming a fanatic with the wrong priorities.

The story of my surprising performance was told often, to my delight, even though my medal was not the point. Elaine’s performance was rated as much more surprising. She completely forgot where she was, my mother would say. It was a public embarrassment, but we laughed it off, knowing it would never happen again. I came to understand that it was perfectly okay to get caught up in the excitement of something pointless like a swimming race while it was going on. This was part of our natural competitiveness, which was fierce but fleeting. No one in the family attended my races after that. I learned to lie to other swimmers and myself about how much I practiced between meets so my victories could always be the result of my natural abilities and my losses could be chalked up to my well-rounded character and coming from a family with good priorities.

The next summer, Joe convinced my mother to let him go to the Catholic Youth Center’s basketball camp for two weeks instead of the regular CYC day camp we’d attended for a couple of years. She sent me along, too, and I blamed Joe for robbing me of the pleasures of adding to my collection of plaster molds of the Holy Family’s Flight into Egypt and squandering whole afternoons in the woods with boys from St. Mary’s and St. Mark’s parishes, who shared their cigarettes and clove gum if you agreed to pee with them on piles of pine needles and bark they set fire to when we were supposed to be capturing a flag. In truth, Joe had argued for keeping me in the regular day camp. He said I was a swimmer, and he was the basketball player. This distinction was lost on my mother.

Joe and David C. and a couple of other skinny sixth-graders with acne practiced lay-ups and passing plays while the shorter kids I liked complained about the Gatorade being warm and begged to go swimming. For a couple of days, the counselors tried to make us run laps in the sun for being lazy, but finally a fat kid threw up and aimed it onto the court, so they dismissed the rest of us most afternoons. All we had to do was take fifty foul shots every day.

It humiliated Joe that I’d sometimes shoot underhand, and he mentioned it every day when we were walking to catch the bus.

I said I was bored.

He said it was bad for his reputation.

I said I didn’t complain about the crazy way he wagged his head when he swam the crawl.

He said how would I feel if he used the dog paddle during free swim?

I started shooting normal foul shots.

In the middle of the second week of basketball camp, an old man I’d never seen before read out ten names, including mine, and said we’d be taking even more foul shots every day. The counselors claimed he was a well-known coach. He had white hair and clip-on sunglasses, like a cop. I figured he was a public school principal they’d hired to work with the discipline problems. I tried explaining to him that I was a natural defense player who never needed to shoot the ball, and he said I should ask at home for high-top sneakers. He was wearing brown loafers and white tube socks and plaid Bermuda shorts. No one in my family ever needed high-tops or nylon-mesh jerseys or even jock straps until we got to high school.

Out of the blue, the old man blew his whistle and announced that all the foul shots had been part of a contest, and we had the ten best records in camp, and the winner would “take home a trophy.” There was only one other kid my age in the final ten, and I knew he had a real chance of winning. His name was Jimmy M., and his father ran the CYC. Jimmy was my size but looked tougher and was not as good a student. I told him I would root for him. He said he would root for himself first and for me second. This was normal for a public school kid, so I didn’t take it as an insult.

Joe didn’t mention anything about the contest, except to say he was glad he’d have more time to practice zone defenses. And he said he didn’t spend much time at the line because he was able to pivot around the defense.

I was surprised to find out I was naturally good at foul shots. During the regular season on the indoor court at the CYC, Coach C. had noticed that a lot of my practice foul shots were hitting the net and sailing out into the vending machine area. He asked me if I thought I could try to hit the backboard once in a while, so team members wouldn’t have to leave the gymnasium so often. Until then, I had thought it was illegal to use the backboard on purpose from the foul line.

Whenever I wasn’t sure about rules, I didn’t ask questions that would make strangers think they were being forced to do my dead father’s work for him. Instead, I made up very strict rules that most human beings couldn’t tolerate, and I figured they would keep me and my father’s reputation safe.

It was relatively easy to hit the backboard compared with shooting the ball right through the hoop, and more often than not, the ball went in. This happened repeatedly during the second week of camp. By Thursday, there was a rumor that I was near the lead. Jimmy M. said he was ahead of me with one tall kid, and he privately showed me a scorecard he’d been keeping for all two weeks. It was written with different color inks for each of the contestants. It made me hope he’d win. He cared about basketball the way Joe did.

On Friday, the coach with the clip-ons announced a shoot-off between me and Jimmy. We had to take turns for a total of twenty shots, five at a time. Jimmy’s father stood with the counselors and watched us. It was another time when having a dead father was an advantage, because there was nobody around to be disappointed or to give you some last-minute advice that cramped your style. Jimmy blessed himself before every shot. I considered this a disrespectful use of praying and just said silent ejaculations, not for me but for the souls in purgatory. I won the contest, and after we got our awards, I immediately told Jimmy it was not important. Jimmy was crying, but only from his eyes. He wasn’t making any sounds. I told him he was way better at basketball than I was, and I didn’t even care about foul shooting. At the time I said it, I was holding the trophy.

Joe told everyone at dinner about my triumph. He tried to make it sound more important than it was, though, so instead of dwelling on the specifics, we discussed how all of the Downings had great aim and could beat other people at horseshoes. I stuck the trophy in a box in my bedroom closet with my swimming medals.

After that, Joe attended all of my CYC basketball games, even when he was a freshman in high school. I was a starting guard for St. Teresa’s by then, though the only points I ever contributed came at the foul line. Even when I had a clear shot, I’d usually look to pass to Jimmy M. or my best friend, Joey T., who was always happy to plow into all the kids standing around in the key and shoot over anyone who was left standing. Coach C. said I was a great team player. I just didn’t want to be the one who missed.

Even when I was in seventh grade, Joe still occasionally tried to get me to practice leg lifts or to play one-on-one, but by then I was allowed to complain right in front of him about taking things too seriously. St. Teresa’s won the CYC league championship that year. Julius Erving was playing for the University of Massachusetts, and he came and gave us our hero jackets and the team trophy, and he was supposed to give us a speech, too. Instead, his eyes rolled back into his head and he fainted and fell off the fake stage they’d set up in the CYC gym. The team was in the front row, so we were able to say we’d saved Julius Erving’s professional basketball career by breaking his fall.

I knew about Julius Erving only from the posters Joe had hung up on his half of the bedroom. He kept them up until his sophomore year. He’d made the junior varsity team as a freshman in high school, and I went to two of his games at the Boys’ Club. He got injured trying out the next year, and when it was clear he wasn’t going to make the varsity team, he didn’t ever play organized sports again. No one at home encouraged him to play a second year of junior varsity. No one asked why he’d stopped wearing ankle weights. He started to devote more and more of his time to politics and religious activities. Everyone thought it was normal for him to quit basketball.

Years later, Joe told me I was the only one in the family who ever saw him play high school ball. I remember being in the bleachers. The arena was really ten times bigger than the CYC, and the court was far away and shiny. I wanted Joe to do well, and I probably clapped when he did, but I’m sure I didn’t stand up and yell his name. If you’d seen me, I would’ve looked like a normal fan, not a fanatic. What you couldn’t have seen, though, was that I was also teaching Joe not to take a junior varsity basketball game so seriously.