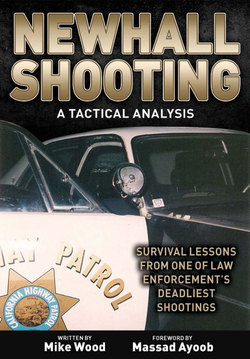

Читать книгу Newhall Shooting - A Tactical Analysis - Michael E. Wood - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 7

More Backup Arrives

At 23:56, when Officer Pence arrived on scene, took fire, and broadcast the 11-99 call, Unit 78-16R (Officers Ed Holmes and Richard Robinson), made another U-turn south of Thatcher Glass Company, directly in front of the oncoming Unit 78-19R (Officers Harry Ingold and Roger Palmer), and the pair of CHP cars responded northbound, Code 3. (Fig. 29)

Officer Ingold would later recall that, as they approached the Saugus Café and began the sweeping left turn onto Henry Mayo Drive, they were exceeding speeds of 130 miles per hour, taking every advantage of the legendary performance of the Dodge Polara Pursuit vehicle.41 They likewise hit the “Edison Curve,” just east of the interstate on Henry Mayo Drive, at 90 mph. To navigate that turn (which was marked at 35 miles per hour), the officers had to drive into the opposing lane, entering high and coming out low as they had been taught in the Emergency Vehicle Operations Course (EVOC) at the Academy.

Less than three full minutes from the start of their response, the units came to a screeching halt and joined the fight, just as Davis and Twining reached their Pontiac in flight, having killed Officers Alleyn and Pence moments earlier.

The total time since Officers Gore and Frago first stopped the Pontiac was only four and a half minutes.

The first unit on scene was 78-16R, who stopped about three car lengths short of Unit 78-8, facing north and slightly east on The Old Road. Gun smoke still hung in the air as Officer Robinson exited the passenger side of the patrol car with a Remington 870 shotgun in hand, narrowly missing being struck by the last .45-caliber bullet from Twining’s handgun, which hit the door of the car after Twining took a shot at his fifth CHP Officer that night. (Fig. 30)42

Officer Robinson hadn’t seen Twining yet, however. The first man that he confronted was the escaping Mr. Kness, who pointed the way to the fleeing felons with one hand, while the other still clutched Officer Alleyn’s empty revolver.43 Officer Robinson crossed the ditch and leveled his Remington 870 shotgun over the top of the fence at the escaping Pontiac, too late to fire a shot. (Fig. 31). It was at this time that he saw the bloody Officer Alleyn, moving slightly on the ground in his green “Ike” uniform jacket, and he realized one of his fellow officers had been hurt.

Meanwhile, Officer Holmes had exited the driver’s side of 78-16R and had seen Twining fire at them. Holmes fired one shot at Twining with his revolver as he was getting into the driver’s side of the vehicle, then once more through the already shattered rear window of the escaping vehicle as it sped off northeast through the gas pump islands with Davis at the wheel and Twining in the rear seat. (Refer again to Figs. 30 and 31.)44

Concurrent with the sound of Officer Holmes’ shots, Officer Robinson saw the Pontiac speeding away through the gas pump islands and noticed that the rear window was “disappearing,” either due to Officer Holmes’ gunfire, or because the movement of the vehicle dislodged the damaged glass that had been destroyed by Officer Alleyn’s shotgun blasts. He crossed the rail fence and went around the backside of the gas station to begin his search for the fleeing vehicle, whose escape he knew would be cut short by the fence and riverbed at the rear of the lot.

Officer Holmes moved forward and saw three of the fallen officers. He checked them out, turned off the motors on the two patrol cars and called Newhall dispatch on the radio, advising that there were three officers down; two were “11-44” (deceased, coroner required), and a third was seriously wounded. He went back to render aid to the dying Officer Alleyn and soon noticed the fourth slain officer. (Refer again to Fig. 31.)45

Arriving on the bumper of 78-16R, Officers Ingold and Palmer also stopped their car northbound on The Old Road, about 100 feet south of the shooting. Officer Palmer exited the passenger side of his unit with a Remington 870 shotgun, crossed the ditch and fence to his right, and entered the parking lot outside of J’s Coffee Shop. He approached a red Chevrolet Camaro, where a witness pointed to the northeast and told him that two officers had been killed in that direction and the suspects were beyond the gas station. Another pair of men behind a black Cadillac told him that two officers had been killed by the people in the departing red Pontiac. (Refer again to Fig. 31.)46

After parking Unit 78-19R and exiting, Officer Ingold initially went to the rear of his unit for a few seconds, seeking cover from the gunfire he heard while he assessed the situation. He quickly moved forward to join the other officers, as the Pontiac was speeding off. (Refer again to Fig. 31.)47

Officers Robinson, Ingold and Palmer began a sweeping search of the parking lot for the offenders, moving in the direction of the escaping vehicle. They were joined by additional officers who’d arrived on the scene from the CHP’s Castaic truck scales facility and other beats. There were a number of large commercial trucks behind the Standard Station that were searched before the officers saw the Pontiac, parked at the end of a dirt road about 150 yards to the northeast of the scene of the shooting. (Fig. 32)

When the Pontiac was spotted, CHP Officer Tolliver Miller cautiously approached the passenger side of the vehicle to clear it for suspects, with Officer Robinson close behind, shotgun at the ready. As they approached the vehicle, they heard Officer Holmes make his “11-44” call to dispatch via the external speakers on each CHP unit at the scene. The officers realized for the first time that their brothers had been killed by the men they were hunting; the men who could still be in the Pontiac they were now approaching. Crouching down below the level of the window, Officer Miller steadied himself with his left hand on the car and slowly raised up to peer through the passenger side window with his revolver in his right hand, its muzzle clearing the bottom edge of the window at the same time as his eyes.48

The car was empty.

In their haste to escape, the felons had chosen a dead-end road that ended with a heavy rail fence at the Santa Clara River. With nowhere else to go, they bailed out of the vehicle on foot, moving towards a dry wash to the north that ran roughly along an east/west axis. The pair split up when Twining returned to the vehicle to get additional weapons, grabbing the shotgun that had been taken from Officer Frago and the revolver that had been taken from Officer Gore. Davis followed the wash to the northeast across the freeway to San Francisquito Canyon, while Twining moved to the southwest, across The Old Road and an open field (now Magic Mountain amusement park), and then south along the foothills that paralleled the highway. (Refer again to Fig. 32.)49

As other officers split up into search teams and fanned out to the north from the Pontiac in search of the escaping felons, Officer Ingold returned to the scene of the shooting, took out a piece of yellow chalk that he used to mark accident scenes, and outlined the fallen bodies of his fellow officers, marking each with the name of the deceased.50

The deadliest law enforcement shooting of the modern era had come to a close.

It had taken four-and-a-half minutes. Learning the lessons from it would take decades.

Endnotes

1. I’ll refer to this event as the “Newhall shooting,” not the “Newhall incident” or “Newhall massacre” as others have. Calling this event an “incident” seems to downplay the significance of this historic lethal encounter, and terming it a “massacre” is equally misleading, since the term conjures images of unarmed or defenseless victims being killed by brutal, armed opponents. While the ruthless and violent nature of the offenders is not in question, the slain officers were certainly not unarmed nor defenseless during the encounter—they were merely overwhelmed by opponents who were better prepared to win the fight.

2. Simply do an Internet search using the keywords “witness memory” for a taste of the voluminous research and literature that exists on the subject.

3. Gibb, F. (2008, July 11) You can’t trust a witness’s memory, experts tell courts. The Sunday Times, <http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/uk/crime/article4312689.ece>.

4. The shooting occurred within approximately 100 to 150 feet of J’s Coffee Shop, which had a large crowd of approximately 40 patrons and employees inside. Many of these people witnessed the shooting from the windows of the restaurant. Meanwhile, in the parking lot, motorists and truck drivers saw the events go down from different vantage points within 150 feet or less of the action. Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. pp.151-153 and Lanning, Rick. Los Angeles Herald Examiner. Los Angeles, CA. 6 Apr 1970.

5. These media contacts were alternately described as reporters from the San Francisco Chronicle by the CHP, reporters from radio station KFWB by print media, and reporters from KNEW radio station by Anderson. Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.177.

6. The CHP’s report said that “more than 40” shots had been fired during the incident, with 15 of them by the officers, but the research conducted for this account of the shooting indicates that the number is closer to 45, with 14 fired by officers and one fired by the responding civilian. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

7. One of those weapons, a Ruger .44 Magnum Deerstalker carbine, was later recovered from their vehicle with a live round jammed in the chamber and four live rounds in the magazine. A second weapon, a Colt 1911A1 pistol, would later malfunction in the middle of the gunfight. Unfortunately, the remainder of the weapons worked as designed. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files and Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.137.

8. Elements of the following narrative sourced from: Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files; interview with Gary Dean Kness; personal interviews with CHP Sergeant (ret.) Harry Ingold and CHP Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson; California Highway Patrol. (1970) Information Bulletin (July 1, 1970): Shooting Incident—Newhall Area. Sacramento, CA, and; Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.131-141, and; California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film]. Sacramento, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/newhall1970-chp1975btv.html> and; Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>. Individual source references will only be provided by exception for the remainder of the narrative.

9. In the CHP’s report of the shooting, they went to lengths to explain that brandishing calls were routine in this rural area and the reported crime was a misdemeanor, not a felony, which may have affected the response and mindset of the officers. California Highway Patrol. (1970) Information Bulletin (July 1, 1970): Shooting Incident—Newhall Area. Sacramento, CA.

10. Alternate versions of Frago’s approach exist. In the CHP Information Bulletin of 1 Jul ’70, the CHP noted simply that Frago approached the passenger side of the vehicle in a “port arms” position and made no mention of him reaching for the door handle, but several witnesses (among them Joseph Tancredi) specifically recalled seeing Officer Frago extend his left hand to open the door while his right held the shotgun with muzzle up in the air in the “hip rest” carry position taught to CHP cadets at the Academy. In the 1975 training film produced by the CHP (with the full benefit of access to the detailed investigation report from Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office Homicide investigators, the CHP’s own investigation report, the official record of the October 1970 trial of Bobby Davis, and the interviews and testimony of the involved parties and witnesses), Frago is specifically described as having reached to operate the handle on the door of the Pontiac with his left hand, so that is the accepted version for this narrative. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files, California Highway Patrol. (1970) Information Bulletin (July 1, 1970): Shooting Incident—Newhall Area. Sacramento, CA, and California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film]. Sacramento, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/newhall1970-chp1975btv.html>.

11. Ironically, this model was known as the “Highway Patrolman,” and in a previous life it had been a duty weapon for the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) The weapon had been sold as surplus by the DPS and purchased as one of a group of 50 weapons by Glenn Slade’s Texas Gun Clinic, a wholesaler in Houston. Salesman Henry Fontenot reported that he had sanded the DPS serial numbers off the guns in compliance with a DPS requirement of sale. Davis had purchased the firearm on March 6, 1970, using an alias. Ten days later, he bought the Smith & Wesson Model 38 Bodyguard Airweight revolver that he used to threaten the Tidwell’s from the same dealer. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

12. It has been reported from reliable sources close to the investigation that Twining admitted to watching Officer Frago in the side and rear view mirrors as he exited the patrol car. During his phone conversation with Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department investigators from the Hoag house, Twining supposedly stated he unlatched his door prior to Officer Frago’s advance, but did not push it open, in a preparatory move for the ambush he was planning. When Twining saw Officer Frago near the car and shift his shotgun from “port arms” to what the CHP training manuals described as a “hip rest” position, he knew he could attack Officer Frago before the officer could get the gun into action. As Officer Frago reached for the door, Twining threw it open and ambushed the unsuspecting officer. Personal interview with a confidential source, July 2011.

13. Davis’ Model 38 revolver would be recovered from the rear seat of the Pontiac after the shooting was over, with five spent cases in the cylinder.

Twining’s Model 28 revolver would be recovered later that morning at another crime scene along the escape path of suspect Davis, in San Francisquito Canyon. When the weapon was recovered by Los Angeles Sheriff’s Deputy Thomas L. Fryer, it had a single spent case in the weapon, which was not resting under the hammer. No other cartridges or cases were in the weapon. Because it was known that a single round had been fired at that second crime scene, LASD investigators initially assumed that it had been fired from this weapon. If this were true, then it would indicate that Twining fired all but this one cartridge in the Standard Station parking lot, instead of emptying the revolver as indicated in the narrative, because the suspect Davis did not have spare ammunition on his person to reload the gun when he fled the original crime scene with it.

However, it was later determined that Davis had another gun in his possession at the San Francisquito Canyon crime scene (Officer Frago’s Colt Officer’s Model Match revolver), and this gun was also found empty with the exception of a single spent case, making it possible that this was the gun that fired the shot instead. The CHP felt that this was the gun used by Davis against Schwartz.

In the wake of inconclusive evidence to prove which gun fired the shot during the escape, it is suggested that it is much more likely the round was fired from Officer Frago’s Colt. It is hard to imagine that Twining would have stopped shooting at the arriving Unit 78-12 prior to running his Model 28 dry, because he did not have another weapon on his person at this stage of the gunfight. It is much more likely that Twining fired all six shots from this revolver at the initial scene, then ditched the weapon in the car when it proved to be empty, whereupon it was later taken away from the scene by Davis. Davis likely dumped the spent brass (save one, perhaps because he mistakenly thought it was a live cartridge in the darkness or thought it could be used to bluff an opponent) sometime during his escape, because the five spent cases were never recovered at the scene of the shooting. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

14. This is the phraseology attributed to Officer Pence in the 1975 CHP training film, but the 1 Jul ’70 CHP Information Bulletin quotes Officer Pence as saying a slightly altered form: “11-99, shots fired, at J’s Standard.” The official CHP radio log, maintained by Dispatcher Jo Ann Tidley, records the call as, “2356: 78-12, 11-99 Standard Station J’s.” Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files, California Highway Patrol. (1970) Information Bulletin (July 1, 1970): Shooting Incident—Newhall Area. Sacramento, CA, and California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film]. Sacramento, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/newhall1970-chp1975btv.html>.

15. Davis’ shotgun was a Western Field 550AD, a re-branded Mossberg 500 12-gauge shotgun with deluxe furniture manufactured for the Montgomery Wards department store chain. This shotgun had a six-round capacity, with one round in the chamber and five rounds in the magazine. Six spent blue Remington-Peters shotgun shells were found at the scene of the shooting, and the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Evidence Lab technicians verified that they had been fired from this weapon. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

16. A single spent shotgun shell, Sheriff’s Crime Lab evidence number JHC #24, was found lodged in the front grille of the Pontiac after the shooting. None of the remaining five shotgun shells that were fired from this weapon were found at the front of the Pontiac, so it appears that Davis only fired a single round with the Western Field 550AD from this position.

17. The sequence of events for Twining’s malfunction and his position during this stage of the fight is driven by the physical evidence at the scene. The Remington-Rand 1911A1 pistol was found on the floorboard behind the driver’s seat with six live rounds in the magazine and a seventh live round jammed in the chamber. An eighth live round was recovered from the ground on the driver’s side of the Pontiac (evidence placard “JHC #8” for Sheriff’s Crime Lab employee Jack H. Clark), the only live .45 ACP round found in the vicinity. An accounting of the evidence indicates that eight other spent .45 ACP cases were found at the scene, all of which were determined to be fired in a second 1911A1 pistol of Colt manufacture that was recovered as evidence. No other .45 ACP spent cases were found at the scene. Therefore, it is likely that the Remington-Rand 1911A1 was not fired at the scene and the JHC #8 live round that was booked into evidence was probably the eighth cartridge that had originally been loaded into the pistol.

This is supported by Twining’s testimony as well. During his phone conversation with Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Detective (Sgt.) John M. Brady, Twining was asked if one of the .45 ACP pistols had jammed on him. Twining responded, “Yeah, I may have got one shot, then it jammed and I got the other.” When asked if he then emptied the second 1911A1 pistol, Twining answered, “Yeah.” Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

18. The CHP’s shotguns were carried in “cruiser ready” condition, meaning they had a full magazine of four Winchester Super X 00 Buckshot shells and an empty chamber. Officer Alleyn had to rack the slide of the shotgun initially to prepare it for firing.

19. Throughout the years, critics have argued the case that the ejected round was an indicator that Officer Alleyn was not competent with the weapon and his training was deficient, but this does not seem like a reasonable conclusion. Forty plus years of experience since the event has shown that officers in gunfights make decisions and take actions that they normally wouldn’t under less stressful conditions, when their minds are not under the effect of powerful, naturally occurring chemicals like adrenalin, which flood the body during periods of peak stress.

Given the extreme stress that Officer Alleyn was under during the initial moments of the ambush, it’s likely that his system was being flooded with stress hormones that effected normal cognitive processes like memory. It’s probable that Officer Alleyn honestly didn’t remember if he had already charged the weapon, so he took the steps required to ensure it was loaded, ejecting the live shell in the process. Because early versions of the Remington 870 shotgun were sometimes prone to double feeding (where an additional round is inadvertently released from the magazine tube at the wrong time in the sequence), it is possible that the live round was intentionally ejected as part of a malfunction clearance, but it’s more likely that the round was simply accidentally ejected as a byproduct of survival stress.

The live round, found near Officer Alleyn’s position at the door of Unit 78-8, was temporarily secured with the shotgun by CHP officers who found it on scene, and was later delivered to Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Crime Lab Sergeant James Warner by CHP Sergeant Cable, along with the CHP shotgun (CHP #39), Officer Pence and Alleyn’s revolvers, and the live cartridges and spent cases from those revolvers. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

20. The Pontiac’s trunk lid bore the scars of Alleyn’s two shotgun blasts, which ran from the right rear corner of the vehicle to the left rear corner of the rear window. The two tracks were 15 inches apart, and the right track showed five paint chip spots and eight skid marks, while the left track showed four paint chip spots and seven skid marks. Additional pellet strikes were seen on the roof pillar, between the left side rear glass and the rear window. The blasts tore out the rear window, leaving only a small rim of shattered, hanging glass along the top edge and left vertical edge of the window. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

Twining made the remarks to reporters and Sheriff’s Department personnel during the phone calls that took place later, after the shooting had evolved into a hostage crisis. Blood from his wound would allow investigators to recreate his movements during the fight later on.

21. While it was not reported by the CHP in either its 1 Jul ’70 Information Bulletin or in its 1975 training film, it appears that Officer Alleyn may have nicked Davis with one of the pellets and came very close to stopping the fight. The lead homicide investigator, former Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office (LASO) Homicide Detective (Sgt.) John Brady, reported that:

“The whole thing almost ended right there. Officer Alleyn hit both Davis and Twining with the shotgun blasts. A pellet from Alleyn’s shotgun streaked across the top of Twining’s scalp, ripping an angry red gash. If it had been just a little lower, it could have opened the top of his skull, or at least knocked him down. Davis was turned sideways to Alleyn. A shotgun pellet tore right over the bridge of his nose. If he had been looking directly back at the officer, the pellet would have hit him right between the eyes.”

The LASO booking pictures of Davis clearly show the wound to his nose. Thus, it was only by the slimmest of margins that Officer Alleyn’s shots were unsuccessful. It’s an appealing exercise to ponder what might have happened if he hadn’t ejected the unfired round prior to shooting and had been able to fire it at Twining after the rear window was ballistically compromised by the previous shots. Kolman, J., Capt.. (2009) Rulers of the Night, Volume I: 1958-1988. Santa Ana, CA: Graphic Publishers, pp. 132-133.

22. The number of spent .45 ACP cases at the scene indicates Twining had the second (Colt) 1911A1 pistol loaded similarly to the first; that is, with a fully loaded magazine of seven rounds and an eighth in the chamber. Based on the pattern of spent cases recovered at the scene, Twining fired three shots from a position somewhere between the driver’s side door of the Pontiac and the left front fender of the Pontiac with the Colt 1911A1 pistol (Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tags JHC #4,5,6) Some witness accounts (Ball, Barth) place Twining back at the front of the Pontiac during this phase of the gunfight, but other witness accounts (Tancredi) contradict that. The pattern of spent cases suggests that he may have fired from a position that was closer to the side of the car than the front, but blood evidence indicates that Twining may actually have been closer to the front of the car. Of note, in the CHP’s account of the shooting, Twining fires on Officer Pence from the front left corner of the Pontiac, using it for cover during this phase of the shootout.

Witness accounts indicate it is possible that Twining engaged both Officer Pence and Officer Alleyn with these pistol shots. A spent .45-caliber bullet was found by investigators on the ground between Unit 78-12 and Unit 78-8, on the right side of 78-12 (Sheriff’s Evidence Tag #23). California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film] and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

23. Crime scene photos show a pair of bullet strikes on the left side of the Pontiac that were likely fired by Officer Pence, due to the angle of impact. One strike is above the gas door at the junction of the rear deck lid and the roof pillar, and another is forward, underneath the left rear side window. The left rear side window itself was also hit near the top center, shattering that window, perhaps by Officer Pence or perhaps by one of Officer Alleyn’s shotgun pellets. It’s likely the pair of rounds that struck the body of the car were fired at Twining as he emerged from the driver’s side and began to engage Officer Pence. There were additional bullet strikes in the dash of the Pontiac that could also have been caused by Officer Pence, Officer Alleyn, or Officer Holmes. The left rear tire of the Pontiac was also flattened when the car was recovered, and it’s possible that Officer Pence or Officer Holmes could have struck it with gunfire. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files, California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film]. Sacramento, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/newhall1970-chp1975btv.html>.

24. The white spotlight on Unit 78-8 was raised and had been hit three times during the fight, presumably by shotgun pellets fired from Davis’ gun. This spotlight would have been directly in front of Officer Alleyn’s face as he kneeled and fired the Remington 870 shotgun in the crotch between the vehicle and the frame of the open door. It is possible that Officer Alleyn was injured by debris from the spotlight after it was struck, or by an actual pellet from Davis’ shotgun, before he left his position at the door.

25. A bullet struck the dashboard of the Pontiac forward of the steering wheel from the rear at some point during the gunfight. The bullet skidded for seven inches along the dash and struck the windshield from the inside, approximately 16.5 inches to the right of the left side moulding, leaving a piece of the bullet jacket in the dash (Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tag #JW3, collected by Sergeant James Warner). Another bullet struck the dash, above the glovebox on the passenger side of the Pontiac. Bullet fragments from this strike were recovered under the hood of the vehicle, about 15 inches towards the center of the vehicle from the right fender (Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tag #JW2). It’s unknown if these two bullets were fired by Officer Alleyn, Pence or Holmes. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

26. Multiple witnesses reported seeing Davis shoot at Pence with the shotgun, and a pattern of three ejected shotshells (Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tags JHC #10,12,13) suggests that one round could have been fired during Davis’ advance on the patrol cars (the other two were known to be fired at Officer Alleyn). Unit 78-12 was struck on the right side by multiple projectiles at some point during the fight, but it is unknown if these strikes were from the revolver gunfire of Davis and Twining as 78-12 arrived on scene, or the single shotgun blast fired by Davis from the front of the Pontiac, which streaked across the hood of the CHP car. It’s possible that none of the earlier shots caused the damage and that it was the result of Davis firing at Pence while he advanced. The right rear window of 78-12 was completely shot out with no glass hanging, and the center of the right passenger window was also shot out, but a rim of shattered glass hung around the edges of the window. There was a hit between the two windows on the vertical portion of the pillar, as well as a hit on the right front fender, about 12:30 to 1:00 position from the tire. There was also a hit on the bottom edge of the door above the running board, at about 5:30 position from the CHP star on the door. The left rear tire was also flat, suggesting a projectile may have skipped underneath the car and struck it. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

27. As previously discussed in Endnote 24, Officer Alleyn may have been wounded at this point, with blood running into his eyes and disrupting his vision and his ability to place accurate fire on Davis.

28. The round fired by Officer Alleyn struck the rear window of Unit 78-8 about 2.75 inches above the moulding and 18.75 inches to the right of the left moulding. The bullet was later recovered from the rear of the driver’s seat, about three inches below the top edge of the seat and in line with the hole in the window. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

29. There are multiple contradictions in witness testimony during this phase of the battle.

Some witnesses claimed that the CHP shotgun had been retrieved earlier in the fight, and there is confusion about whether Davis or Twining was the person who picked it up. However, the preponderance of evidence suggests that the shotgun had not been retrieved prior to this point and that Davis was the one to recover it.

A witness claimed that Davis struggled with the CHP shotgun and inadvertently fired it while trying to work the gun. After the accidental discharge, the shotgun was placed in the car, according to the witness. Importantly, this testimony matches the CHP’s version of the event, as well.

The physical evidence tends to discredit this narrative, however. An accounting of the ammunition from this shotgun indicates that one spent CHP shotgun shell and three live CHP shotgun rounds were found with the weapon at the Hoag house, where Twining had taken hostages later in the day during his escape attempt. The spent shell was found in the hallway of the Hoag house next to Twining’s dead body, along with two other spent shells supplied from Twining’s own stock. (Fortunately, the brand and hull color of the CHP’s shotgun ammunition differed from the ammunition that the felons brought to the fight, making it easy to identify the source—the CHP issued Western Super-X ammunition with red hulls, while Davis and Twining had brought Remington-Peters ammunition with blue hulls to the fight.) Because Twining had engaged Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies with multiple shots from the shotgun in that location during two raids on the house, it is believed that the CHP shotshell was fired in the hallway of the Hoag house and not at the Standard Station location. Furthermore, it is inconceivable that the weapons-savvy Twining would have waited to eject the spent CHP shotshell and make the gun ready with a live round until starting the gun battle with Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies in the hallway of the Hoag household. He most certainly would have ensured the gun had a loaded chamber at some time during his three-mile flight from the scene, particularly before he used the gun to take the Hoag family hostage. This makes the accidental discharge theory even less plausible and tends to confirm the accounts of witnesses who did not see the accidental shotgun discharge occur.

There is an additional matter that Davis should not have been confused by the operation of the CHP shotgun, which was virtually identical to his own. The location of the button that releases the fore-end and the safety button are different on the Remington 870 and Western Field 550 designs, but it’s unlikely this would have confused the weapons-savvy Davis enough to cause an accidental discharge.

Interestingly, other witnesses claim that Davis fired Officer Frago’s shotgun or revolver at the fallen officer, at contact range, after he had taken them away from him. However, the coroner who performed the post-mortem examination on Officer Frago found no evidence of additional wounds beyond the two gunshot wounds from Twining’s revolver. Additionally, there was no physical evidence that indicated such a shot was taken (spent cases, impact marks on the asphalt, etc.). It is much more likely that these witnesses saw the muzzle blast from Twining’s handgun, which was simultaneously being fired beyond Davis on the opposite side of the Pontiac, and mistook it for fire from Davis. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

30. Interview with Mr. Kness and Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson, who was present when Mr. Kness made his initial statement to Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department investigators after the shooting. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html> and personal interview with Richard Robinson.

31. In Mr. Kness’ own words, Officer Alleyn “was dead weight to me” when he attempted to drag him to cover and he couldn’t move him. Because Davis was still firing at them, Mr. Kness tried to shoot him with the shotgun, but when it clicked on an empty chamber he “got a sick feeling.” When the shotgun clicked on an empty chamber the second time, he “really got a sick feeling.” Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>.

32. Mister Kness reported that, when he first picked up the revolver and attempted to cock it, his thumb had a hard time finding the hammer spur. He then grabbed the revolver by the barrel with his left hand, placed his right hand on the grip, and successfully thumb-cocked the revolver. He then mated his left hand to the right in a “two-hand combat position” to fire the shot over the trunk with his elbows resting on the vehicle. Mister Kness later told investigators that he was a little surprised the weapon fired, because after having two dry fires on the shotgun earlier, he didn’t know if the revolver would dry fire, too. Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html> and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

33. Several witnesses would recount that Davis clutched his chest or armpit area and spun away like he had been hit, and Mr. Kness said that, “I knew I had him, because he spun around.” Davis was later found to have a 1” long wound under the armpit at the hospital, but it’s not clear if this wound came from Mr. Kness’ shot or from one of Mr. Schwartz’s shots later.

The “wing window” trim on the passenger’s side door of the Pontiac was hit by a bullet at some point during the fight, and bullet core and jacket pieces were later recovered from the vehicle in this location (Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tag #JW1). A hit in this area would have been in line with Mr. Kness’ position at the right rear of Unit 78-8 and Davis’ position at the front bumper of the Pontiac, and it is possible this is where Mr. Kness’ bullet struck, sending fragments into Davis. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

34. There has been some limited discussion as to whether or not Mr. Kness wounded Davis with his revolver shot, or if the wounds were sustained during Davis’ later encounter with another civilian after he fled the scene. The evidence indicates that the wounds Davis received in the later fight were to his neck and collarbone area. Also, since Mr. Kness was shooting at Davis from a very close distance and saw him spin away as the shot was fired, and since Davis disengaged at this point of the fight, it is most likely that Mr. Kness did indeed hit Davis with a fragment of a bullet, as indicated in the narrative. California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film]. Sacramento, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/newhall1970-chp1975btv.html> and Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.157-158, and Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>.

35. Although he could not have known it at the time, it appears that Officer Alleyn’s gun was not empty and that Mr. Kness actually had one additional live round left in the cylinder.

When the fight was over, Officer Alleyn’s Model 19-2 revolver was recovered by CHP Officer Jack Burniston and placed in CHP Sergeant P.M. Connell’s car, along with Officer Pence’s loaded revolver and Officer Alleyn’s empty shotgun. One live round of .357 Magnum ammunition was recovered with Officer Alleyn’s gun, in addition to five spent cases.

It’s conceivable that Officer Alleyn tried to cock or fire the revolver earlier in the fight, but did not work the hammer or trigger all the way, perhaps because the bloody revolver was so slippery. This short stroke could have advanced the cylinder far enough to line up the next round, but since the hammer was not brought fully back (in either single- or double-action), or the trigger was released forward before the sear tripped, the round under the hammer was not fired. A subsequent trigger stroke or manual cocking of the hammer would have advanced the cylinder again, skipping this live round.

In such a sequence, rounds numbers one through three were fired by Officer Alleyn, round number four was somehow skipped, round number five was fired into the rear window of 78-8, and round number 6 was fired by Mr. Kness at Davis.

It’s plausible that such an action occurred after Officer Alleyn was shot by Davis with the shotgun, at the rear of Unit 78-8. The horrible wounds suffered by Officer Alleyn could have caused him to short stroke or release the trigger as he clung to life and desperately tried to continue fighting. The live round would have been skipped immediately before Officer Alleyn was struck a second time by Davis’ buckshot and before he triggered his final round into the rear window of Unit 78-8.

Alternatively, the round may have been skipped by Mr. Kness himself, who reported difficulty with cocking the gun properly after he picked it up from the ground. After reacquiring a better grip, Mr. Kness was able to cock the revolver and fire it once at Davis, before a spent case found its way under the hammer for the subsequent attempt.

Again, Mr. Kness could not have known there was another live round in the gun. After two unsuccessful attempts to shoot the empty shotgun, it’s entirely reasonable that he assumed the revolver was also completely empty when it clicked dry on the second attempt. It’s simply a shame that fate and the friction of war intervened to deprive him of a second chance to fire at Davis. Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

36. Unit 78-16R (Officers Holmes and Robinson) in the lead with Unit 78-19R (Officers Ingold and Palmer) behind.

37. When he attempted to fire the revolver a second time and the hammer fell on an empty chamber, Mr. Kness decided to leave the scene. Simultaneously, he heard a boom “like a 105mm howitzer going off, but it was only a .45.” The boom was the 1911A1 pistol being fired by Twining at Officer Pence. Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>.

38. Officer Pence’s reload has been the subject of much discussion and debate. It has been widely reported that Officer Pence reflexively pocketed his spent brass as he had been conditioned to do in range training at the CHP Academy. It has been reported that the spent brass was found in his pants pocket during the post-mortem examination, and this supposed “fact” has been used to support a multitude of theories about the quality of CHP training and Officer Pence’s presence of mind during the fight.

It is categorically false that Officer Pence pocketed the spent .357 Magnum brass during the gunfight. His pile of spent .357 brass, marked by Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department evidence tag JHC #18, was found on the ground abeam the rear door on the driver’s side of the vehicle, right where Officer Pence was reloading his weapon before he was murdered. Evidence photos show the brass in that location, and the witness testimony of retired CHP Sergeant (then, Officer) Harry Ingold, who checked on Officer Pence and marked the spot he had fallen in the immediate moments after the fight, supports it. Sergeant Ingold specifically recalls seeing the spent brass on the ground in that location; the same location reported by Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department Criminalist Jack H. Clark when he tagged it “found by side of vehicle #2” and had it photographed as evidence item #18 (JHC #18), hours later.

This brass was also mentioned in the report of the lead investigator, Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide Sergeant John Brady, who said that when they arrived at 00:50 hours (less than an hour after the shooting ended), and began their inspection of the crime scene, he noted “several expended shell cases, possibly .38 or .357” on the ground.

It’s critical to note that the only spent revolver brass found loose on the ground at the crime scene was the brass near Officer Pence’s location.

The spent .38 Special revolver brass in Davis’ Model 38 revolver was still in the revolver, which was left in the rear seat of the Pontiac. The spent .357 Magnum revolver brass in Twining’s Model 28 revolver was dumped during the flight from the crime scene and never recovered, except for the one case that remained in the gun as it was found at the scene of the Schwartz robbery by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Thomas L. Fryer. The spent .38 Special revolver brass in Officer Frago’s Officer’s Model Match revolver was also dumped during the flight from the crime scene and never recovered, except for one case that was found in the gun when it was located in the camper of Schwartz’s vehicle and booked into evidence by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputy Don G. Tomlinson. The spent .357 Magnum revolver brass (and single live round) in Officer Alleyn’s Model 19 revolver was recovered with his gun and secured at the scene by CHP Officer Jack Burniston, who put them on the floorboard of CHP Sergeant Paul Connell’s vehicle. These cases were later booked into evidence, when they were delivered by CHP Sergeant Cable to the LASO Crime lab. The single round of spent .357 Magnum brass fired in Officer Gore’s Colt Python revolver was recovered from the floor of the Hoag residence by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Detective Sergeant John Brady. The remaining handgun cartridge cases at the scene came from Twining’s .45 ACP pistols.

The brass marked JHC #18 was later examined by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Crime Lab, where Sgt. James Warner determined that the brass had been fired in Officer Pence’s Colt Python revolver.

There is no mention of the spent brass in the detailed post-mortem report completed by Los Angeles County Coroner Gaston Herrera, M.D.

In summary, the only spent revolver brass that was found loose on the ground at the crime scene was the brass marked JHC #18 by Sheriff’s investigators. This JHC #18 brass was found in the location where Officer Pence was completing his reload when he was murdered. It was seen there by an officer who was the first on the scene and remembers seeing it in the immediate moments after the fight. It was also seen by the lead investigator for the homicide (who was from another agency), within 50 minutes of the end of the gunfight. It is not possible that this brass came from another weapon at the crime scene, as scientific examination verified that this brass was fired in Officer Pence’s revolver, and all other revolver brass at the scene was accounted for.

There is no reason to believe that the brass was recovered at the Coroner’s Office in Officer Pence’s pocket during post-mortem examinations, then transported back to the scene of the crime to be fraudulently deposited there, as some have speculated. The timeline doesn’t support such a theory, because the bodies had not been transported to the coroner yet when Sgt. Brady first arrived on scene and saw the brass on the ground. Additionally, to coordinate this kind of conspiracy, a large number of people from different agencies would have to have been compelled to lie about a very minor detail of the case, at a time when the investigation was just beginning and they were struggling to understand the very basics of what had occurred during this monumental event. It hardly seems likely that this minor detail of evidence would have been perceived as critical enough to warrant a conspiracy to lie this early in the case.

Officer Pence did not pocket his spent brass.

In the wake of Newhall, the CHP made an intensive study of training practices and made many corrections to ensure that bad habits that would jeopardize officer safety on the street were not taught during training. One of these corrections was a requirement to eject brass onto the ground during training and clean it up later, rather than eject it neatly into the hand and drop it into a can or bucket, as had been the practice before. It is believed that instructors and cadets of the era may have mistakenly believed that this change in policy was due to a specific error made by Officer Pence during the fight. The myth began, and it was innocently perpetuated throughout generations of officers in the CHP and allied agencies.

Anderson states that the rumor was propagated by law enforcement trade publications of the time, which really sealed the “fact” into the collective memory of the law enforcement profession. This is certainly the case with contemporary gun and law enforcement magazines, which have continued to treat this myth as fact, some 40-plus years later.

This does not detract from the valuable training lesson embedded in the myth. It is important that negative habits that can jeopardize safety are not encouraged during training. These “training scars” must be avoided, and the “pocketed brass” story is an effective and relevant metaphor to prove this lesson. There have indeed been other documented cases of this phenomenon occurring (pocketing spent brass), but it did not occur at Newhall.

Personal interview with CHP Sgt. (ret.) Harry Ingold (2011), and Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.146 and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

39. CHP Officer Harry Ingold recalls that, after the fight was over, Officer Pence was found slumped forward with his knees and face on the deck, the brim of his uniform hat trapped between the ground and his forehead. His hands were trapped under his body near the waist and not in sight. When Officer Pence’s torso was raised up, his revolver was found in his hands with the cylinder open and six rounds of live .357 Magnum ammunition in the cylinder, indicating that he had almost completed his reload before he was executed by Twining.

Anderson describes that Officer Pence had fumbled two of the six rounds during the reload and was able to recover one of them from the ground and load it in the revolver before he closed the cylinder, but it’s not clear how the number of fumbled cartridges was known, and other elements (number of loaded cartridges, cylinder closed, etc.) conflict with Officer Ingold’s clear recollection of an open cylinder with six cartridges. Massad Ayoob’s narrative, based on the CHP’s version, confirms the notion that Officer Pence was able to reload all six cartridges before he was executed.

Disturbingly, it appears Officer Pence wasted precious moments immediately before he was executed by Twining. Had he accepted a partial load of the gun and returned quickly to the fight, instead of fully loading the revolver, he might have been able to close the cylinder on his revolver and fire upon Twining before Twining could deliver the final killing shot. Of course, it must be realized that Officer Pence was horribly wounded at this point and his body and mind were under tremendous stress, both of which would make this kind of detached, analytical thinking exceptionally difficult, if not impossible. Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.146, and Ayoob, M. (1995) The Ayoob Files: The Book. Concord, NH: Police Bookshelf, p.122, and California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film], and personal interview with CHP Sergeant (ret.) Harry Ingold (2011)

40. Mister Kness heard Twining make the comment and saw the execution shot immediately after his unsuccessful attempt to fire a second shot at Davis with Officer Alleyn’s revolver. Hearing the “105mm Howitzer” boom of Twining’s pistol and seeing Officer Pence go down was the final straw that convinced him he needed to escape. Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>.

41. Officer Ingold remembered the Polara’s speedometer was indexed up to 130 miles per hour and the red needle of the speedometer was in the black, past this last unit of measure.

The 1969 Polara was the most famous and adored of all the CHP cruisers, because it was the king of speed. During the test trials at Chrysler’s track in Chelsea, Michigan, the 440 cubic-inch, 375 bhp (brake horsepower) muscle car set a track record for the highest top-end speed achieved by a factory built four-door sedan—an impressive 149.6 miles per hour! The record remained unchallenged for 25 years, and even then there are those who question whether the 1994 Chevrolet Caprice (with its specially tuned Corvette engine), honestly and fairly beat it. Huffman, J. (1994, June) Chrysler Police Cars 1956-1978. Motor Trend Magazine, 102-106, and Ellestad, S. (n.d.) The History of Chrysler, Dodge and Plymouth Police Cars-1969. [Online], <http://www.allpar.com/squads/history.html> and “Grant G.” posting as “Granttt73”. (n.d.) [Online], <http://www.flickr.com/photos/13411027@N00/566744694/>, and personal interview with CHP Sergeant (ret.) Harry Ingold (2012).

42. At the time, neither Officer Robinson nor Officer Holmes realized that their car had been hit by gunfire. After spending most of the morning participating in the manhunt for the felons and giving statements to investigators at the scene, the two officers took their unit back to the Newhall Area Office to do volumes of reports. While there, the day shift officers reported for work and received their beat and unit assignments. The officer who was assigned Officer Holmes and Robinson’s vehicle discovered the bullet strike during his pre-shift walk around inspection, and found Officer Robinson to question him about it. Incredulous, Officer Robinson followed him outside to look at the vehicle, and realized for the very first time that one of the felon’s bullets had struck above the “H” in the “Highway Patrol” rocker, dotting one of the bars “like a lower case ‘i’.” It was then that Officer Robinson realized how close he had come to getting shot as he bailed out the door. Personal interview with Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson.

43. In the stress of the event, Mr. Kness didn’t realize he had the empty revolver in his hand until he ran into Officer Robinson. It was then he realized that he was covered in blood, holding a gun, and fleeing from a shooting scene, none of which looked good. Hiding the gun behind his thigh, Mr. Kness directed Officer Robinson towards the killers and hoped that the officer wouldn’t think he was one of them. Fortunately for Mr. Kness, Officer Robinson had not consciously noticed him or the gun. Officer Robinson later recalled that in the extreme stress of the moment, he was so totally focused on the escaping Pontiac that he had no memory of running across Mr. Kness at all. Whether it was Officer Robinson’s extreme focus on the Pontiac/threat (tunnel vision?) or his rapid subconscious assessment of Mr. Kness as a “friendly” who didn’t bear further investigation, Mr. Kness fortunately escaped becoming the tragic victim of fratricide. After the brief encounter with Officer Robinson, Mr. Kness sat down in the ditch and waited, emotionally spent. Interview with Mr. Kness. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>, Personal interview with CHP Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson, and Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department homicide investigation files.

44. The sequence of events during this part of the shooting is not entirely clear. In the CHP narrative of the shooting, Officer Holmes fires at Davis as Davis is getting into the driver’s side of the vehicle, and then fires again at the Pontiac as it speeds off through the gas pump islands.

However, in his report that was filed that morning, Officer Holmes wrote that, as they arrived on the scene, he observed a suspect at the rear of Unit 78-12 by Officer Pence. This suspect ran to the left rear of the Pontiac, turned, and fired once at Officers Holmes and Robinson as Officer Holmes was getting out of the door. The suspect fired with his right hand across the rear trunk deck, and then entered the vehicle on the driver’s side. Officer Holmes fired at this suspect with one shot.

This suspect would have been Twining, not Davis. Twining had just executed Officer Pence and was standing near him. Additionally, Twining is the suspect that fired at Officers Holmes and Robinson as they arrived, according to the CHP narrative and witness statements.

Adding to the confusion, Officer Holmes described the suspect as wearing a yellow shirt, but it was Davis who had a yellow windbreaker on during the shooting, not Twining. Twining was wearing a green sweatshirt. Perhaps it took on a yellow tint under the neon lighting from the gas station, or perhaps Officer Holmes was just confusing the details of the fast-breaking situation.

So, while it is unclear whether Officer Holmes fired at Davis or Twining, it is presumed that his memory of firing at Twining (the suspect who was near Pence when they arrived, and who shot at them), was correct.

Other witness testimony about this phase of the fight is also unclear, particularly when it comes to how Twining entered the Pontiac. Some witnesses reported that Twining entered the vehicle on the driver’s side after Davis and pushed Davis out of the way. Others reported first seeing Twining entering on the driver’s side, then witnessed considerable movement and hearing shouting within the vehicle before it drove away. Still others reported that Twining entered the vehicle on the passenger side, perhaps confusing the timeline for when he entered the vehicle this way earlier in the fight to obtain the 1911 handgun on Unit 78-12’s arrival.

The blood inside the vehicle suggests that Twining may have crawled into the back seat before they fled, because there is a noticeable preponderance of Twining’s blood in the rear of the vehicle (particularly on the driver’s side) and almost none in the front. There is no noticeable blood on the front passenger seat. The few drops of blood found on the inside of the passenger side door were probably deposited as Twining rummaged through the vehicle looking for weapons and ammunition. If Twining crawled into the back seat when Davis was already at the wheel, this would explain some of the movement that was reported by witnesses.

In this scenario, Twining would have approached the driver’s side with the intention of driving the vehicle away, only to realize that the driver’s seat was already occupied by Davis. At this point, Twining would have climbed into the back seat of the vehicle because it would have been faster and would have allowed him to get behind cover more quickly.

This assumption is further reinforced by the fact that both felons exited the Pontiac out the driver’s side of the vehicle when it came to a stop. The abandoned car was found by officers with the passenger side door closed.

California Highway Patrol. (1975) Newhall: 1970 [Film], Personal interview with CHP Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson, and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

45. Officer Alleyn died enroute to Golden State Hospital. This is the format of Officer Holmes’ radio call per the California Highway Patrol, but Officer Holmes’ partner, Officer Richard Robinson, clearly remembers the shocking radio call differently. Officer Robinson vividly remembers Officer Holmes stating, “11-41, three, no, four possible 11-44” (ambulance required, three, no, four possible dead). Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. p.163, and personal interview with Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson.

46. Interview with former CHP Officer Palmer. Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html> and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

47. Interview with CHP Sergeant (ret.) Ingold and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

48. Personal interview with CHP Officer (Retired) Richard Robinson.

49. Davis encountered Daniel Joseph Schwartz during his escape and fired a single shot at him while Mr. Schwartz was inside the camper shell on his 1963 International Scout pickup. Mr. Schwartz blindly returned gunfire through the door of the camper with his Enfield No.2 Mk I* revolver, chambered for the relatively impotent .38/200 (or .38 S&W) cartridge. One of his three bullets struck Davis and slightly wounded him, according to the CHP. The weak bullets didn’t have much energy after penetrating the camper, which is why Davis was not more seriously wounded.

After Davis threatened to burn him out, Mr. Schwartz exited the vehicle and fired his remaining three rounds at Davis (perhaps wounding him again—Davis had an armpit wound and a wound to the right neck/collarbone area), whereupon Davis clubbed him with the now empty revolver that he had stolen from the dead Officer Frago.

Having savagely beaten Mr. Schwartz, Davis escaped in the truck, only to be captured by Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Deputies Fred Thatcher and Don Yates at a roadblock along San Francisquito Canyon Road around 04:15 on 6 Apr ’70.

Twining escaped in the hills to the south on foot and attempted to steal a car at the residence of Steven G. (alternately, “Glenn”) and Betty Jean Hoag around the same time that Davis was captured. When he was discovered by Mr. Hoag, he took him hostage, using the CHP shotgun. Mis’ess Hoag had enough time to call the nearby CHP Newhall office (half a block away, at the bottom of the hill!) and ask for help before Twining took her hostage, as well. Responding CHP Officers and LASO Deputies rescued Mrs. Hoag and her teenage son, but Mr. Hoag remained captive until Twining released him approximately five hours later. After negotiations failed, a team of LASO Special Enforcement Bureau (SEB) Deputies launched a tear gas attack on the house, shortly retreated, then reentered the home after the gas had cleared somewhat. Twining committed suicide with Officer Frago’s stolen shotgun during the ensuing gunfight. Anderson, J., & Cassady, M. (1999) The Newhall Incident. Fresno, CA: Quill Driver Books. P.155-180, and Kolman, J., Capt.. (2009) Rulers of the Night, Volume I: 1958-1988. Santa Ana, CA: Graphic Publishers, pp. 134-139 and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Homicide investigation files.

50. Interview with CHP Sgt. Ingold (ret.). Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. (2010) The Newhall Incident: A Law Enforcement Tragedy [Film]. Santa Clarita, CA, courtesy of Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society and SCVTV, <http://www.scvtv.com/html/scvhs040510btv.html>.

SPECIAL SECTION

Photo Gallery

Aerial view of the crime scene, with J’s Coffee Shop in center and Standard Station at bottom left. The Pontiac was abandoned at the end of the road at middle left, but towed back to its origin during reconstruction, as shown. (Photo courtesy of California Highway Patrol)

Day breaks on a murder scene. Officer Alleyn’s cap on Unit 78-8 in foreground, Officer Pence’s cap on ground by Unit 78-12 in background. Pools of blood mark the positions in which these valiant officers were slain. The blanket near 78-12 was placed over the fallen Officer Pence by Citizen-Hero Gary Kness when the smoke cleared. (Photo courtesy of CHP Sergeant [Ret.] Harry Ingold).

As the sun comes up, Units 78-8 and 78-12 are visible with CHP Sergeant Paul Connell’s car in background and evidence markers in foreground. The portable spotlights on the curb helped investigators to work the scene throughout the night. (Photo courtesy of CHP Sergeant [Ret.] Harry Ingold).