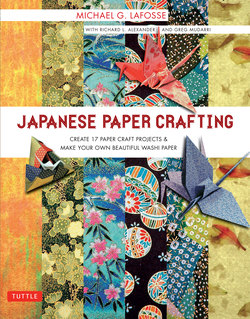

Читать книгу Japanese Paper Crafting - Michael G. LaFosse - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеWASHI

The Magnificent “Skin” of Japan

The word “washi” is a combination of two Japanese words, wa and shi. Taken literally, “wa” means “peace,” and “shi” means “paper.” However, when used together, they have come to mean “Japanese paper,” with the “wa” prefix now representing the essence of Japanese culture. Nowhere else but in Japan does a culture seem so intimately associated with fine papers. For centuries, the Japanese have embraced the exploration of paper’s potential. Through this exploration, they soon realized that washi could become so many things, including clothing, lanterns, parasols, fans, windows, room screens, masks, and ceremonial decorations.

Japanese handmade papers are as beautiful, genuine, and interestingly varied as Japan itself. The patterns chosen to decorate washi are typically icons of the rich Japanese culture, landscape, and history. Like washi, Japan can show its bright colors, bustling noise, and excitement, but it can also show its softer, natural, tranquil side. From bright, silk kimono–inspired Yuzen patterns to subdued, creamy, silky whorls, washi offers a magnificent “skin” that expresses and defines Japan.

Washi is beautiful, not only on the surface but throughout: Washi’s inherent character tends to shine through, even when its surface is printed, painted, or dyed. Its simple beauty belies the extraordinary effort taken to create luxurious paper with soft and supple strength.

Washi is not only beautiful but endlessly varied. Its raw materials are products of the Earth, and the three major species of plants harvested to become washi— Kozo, Mitsumata, and Gampi—are each unique, making their own inimitable contribution to the final product. Geography, topography, and local weather conditions affect these plants, which can grow quite differently in the various regions of Japan, and add to the individual personalities of the paper. These subtle differences in fine papers, like scrumptious foods and exquisite wines, do indeed enhance a civilized life. The Japanese people have long realized this and seem to respect high-quality paper perhaps a bit more than others do. So I call washi the magnificent “skin” of Japan for these reasons, but you do not have to be Japanese to appreciate, make, or use washi.

THE SPECIAL QUALITIES OF WASHI

There are countless different kinds of washi, yet there are certain recognizable qualities that set it apart from similar, western-style papers. People who encounter washi for the first time remark that it resembles cloth more than it does paper, which is probably a fair assessment due to its softness, both in look and feel. Although washi may feel soft, if made correctly it is exceedingly strong, even when wet. Its folding and tensile strength measurements are often quite high, due to the length and quality of the fibers. Its strength allows washi to be employed as a basic material for fabricating a staggering range of durable, utilitarian, and decorative items.

The overriding element that makes washi so different from other paper is that washi has a refined beauty, found even in its coarser forms. Certainly, some of this special beauty results from the care in selecting, harvesting, handling, and processing the fiber, but much comes from the skill of the papermaker. Most agree that the painstaking labor of making washi by the time-honored, traditional hand methods results in paper that reveals the inherent honesty of the materials. Soetsu Yanagi wrote, in “Washi no bi” (The Beauty of Washi), “The more beautiful it is the more difficult it is, to make trivial use of it.” This is perhaps the greatest stumbling block for most people who love and purchase washi: It is too beautiful to use! Sure, you can frame it, or just keep it in drawers and look at it every so often, but washi begs to be used, and this book presents a series of delightful projects that can help you provide a suitable stage for its full appreciation.

Most people limit their thinking about using washi to simply wrapping or covering things, but with some clever techniques washi comes alive with shape and form. Even artists and craftspeople who routinely use other paper in their work enjoy the qualities of washi, yet they often avoid it because of its softness, opting for stiffer, machine-made papers. The fact is that, even though most washi wears quite well, it often must be lined, backed, or stiffened before use. This book will show you how to prepare your washi for all manner of applications. This and other essential preparation techniques will allow you to greatly expand the possibilities for using washi in your artwork or incorporating it into your surroundings to liven up and enrich your everyday life at home or at work. These techniques are not complex, but few books explain them. No wonder so much of the finest papers sit unused in the dark.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF WASHI

Scholars believe that papermaking began in China perhaps twenty-one centuries ago. It is likely that the method of making sheets of felted plant fiber became known in Japan perhaps five or six centuries later by way of trade with Korea. Certainly, papermaking methods flourished along the Silk Road trade routes to the Middle East, because paper was as useful for wrapping and separating items for sale as it was for documenting the trade transactions.

There are a staggering number of books about handmade paper and papermaking, many with instructions about how to make paper out of almost any kind of plant and recycled fibers. Those books are not about washi. Novelty papers such as those made from grasses, leaves, or weeds have their charm, but the fact is that paper as supple yet as strong and as versatile as washi is just not possible from most plants.

Making washi is somewhat akin to making fine wine. Certain types of washi are made in specific regions of Japan and often carry the names of those locations, much as fine wines may be named for the specific regions in Europe where special grapes were cultivated and unique winemaking methods were developed to process those particular grapes. Likewise, the choicest paper is skillfully made from only specific sections of carefully cultivated and harvested plants, grown in just the right regions, harvested at just the right time. The growing location is critical, because the climate dictates the plant’s growth rate. The process selected for making a particular type of washi depends on the characteristics of the source materials, so it must be adjusted and refined accordingly. There are so many variables in making washi that the analogy of making fine wine is not too far off the mark.

Washi is produced by processing select bast fibers from only a few species of plants, particularly from the paper mulberry (Kozo), Mitsumata, and Gampi. These bast fibers come from the clean, nearly white, inner bark layer, also called the phloem (not the dark, outer bark). Under a microscope, the phloem is a complex, lacey plant tissue, a system of specialized cells including vertical sieve elements, with sieve plates located at the top and at the bottom ends of these long, skinny cells. There are also companion cells surrounding the sieve elements, thought to provide nourishment and functional control of the transportation and movements of sugar and mineral solutions. This tissue achieves a rapid transport of fluids between cells.

In contrast, on the inner side of the growing, cambium layer of cells, are the woody tissues, including the xylem and the pithy, structural core. These layers consist of stiffer, tougher, and thicker cellulose, with smaller cell walls that become woody from amorphous, polymeric deposits made by the plant. These woody tissues require a greater amount of processing, both mechanical and chemical, to make even a low-grade paper, such as that used for disposable napkins, toilet and facial tissue, or inexpensive office paper.

In the washi-making process, after the stems are cut, the bark is stripped off the wood, the bast fibers are separated from the darker bark, and the thin, green, growing layer of undifferentiated cambium is scraped away. At this stage, the fiber is often dried and shipped to processors. Processing the bast fibers by boiling in a caustic (alkaline chemical) solution digests, and allows the removal of, the cambium and companion cell protoplasm. Bits of bark, lignin, and semi-digested cambium still adhere to the mash and must be removed, often by hand with tweezers. Boiling thus makes it easier to clean, separate, and splay the remaining tubes of sieve element tissue. The fraying of these strong, long fibers in the beating process allows them to knit together in a tangled mat as the sheet of paper is being formed. This increased surface area becomes “hydrated” during beating, which allows these sites to be attracted to each other by hydrogen-bonding. The length and strength of fibers, the correct degree of hydration, and the intimacy of physical entanglement makes for strong, supple washi.

Expert papermakers were so fastidious about removing any contamination (or chiri) and discarded so much useful cellulose with the waste that they were able to make low-grade paper with the dregs. This is called chirigami. Because the best paper-makers rejected more impurities, and thus more bast along with them, even their waste paper was strong. It was said that the best way to judge a papermaker was to evaluate the quality of his chirigami. Today, these papers are appreciated for the flecks and bits of impurities that lend chirigami a rustic, earthy quality.

KINDS OF WASHI

Although there are dozens of types of washi, this section describes the general categories of washi that you are likely to find today. Traditionally, washi was formed and treated in special ways to produce paper for different purposes, therefore with different qualities. Maniai-shi included paper with clay added to keep it from puckering, especially useful when the paper will be hung from the wall as backing for artwork or a sign. Waterproof papers made by oiling washi with rapeseed were used for packaging, umbrellas, and raincoats. Tougher, thicker papers were made for tags and cards, while thinner papers, called usuyo-shi, were primarily used for filtration, packaging delicate items, and artful wrapping.

There are excellent books on washi that break these major categories into several subsets of washi types. Though the names of the same papers in different locations and countries have changed over time, resulting in some confusion, this book uses the most recent and common trade names, which you are likely to find in catalogs, on the Internet, and in paper shops. In this book we will focus on the techniques that will help you use washi successfully, regardless of its common name or makeup. The following descriptions and photos will help you to identify and select the proper washi for each project and give you an idea about the types of washi-like papers you may wish to make yourself.

Natural washi is white to tan in color and is made from one or more of the three traditional washi fiber sources: Gampi (Wikstroemia diplomorpha), Mitsumata (Edgeworthia chrysantha), and Kozo (Broussonetia papyrifera). Natural washi may be brightened by drying in the sunlight, but it is usually not colored by additives such as dyes, pigments, or clay.

Dyed washi is available in many colors and weights. Dyes, however, are usually not light-fast, so be careful before you choose solid-colored washi for a project you want to display in sunlight or keep for generations.

Chirigami is natural washi with chopped bits of the dark bark included. The result is a rustic-looking paper, flecked with dark flakes and strands.

Chiyogami washi is decorated with patterns, animals, flowers, symbols, and auspicious icons, to illustrate traditional celebrations and the changing seasons. It is traditionally printed using woodblock techniques. Chiyogami stenciled with kimono fabric–inspired patterns, called yuzen, is also popular. Traditionally, a separate stencil or woodblock is used for each color.

Tie-dyed and/or fold-dyed washi is colorful, often with kaleidoscopic patterns that are produced by folding, twisting, tying, and dying the paper. Elaborate patterns result when the process is repeated using different dyes and other physical restraints, masks, or resists.

Momigami is washi that has been crumpled by hand to give the paper texture. A special paste, made from konnyaku starch from the root of the Amorphophallus konjac plant, is then applied, usually to one side only. The paper is then crumpled, opened, and crumpled again. Done repeatedly, the process develops an intricate surface texture, similar to crepe paper, and the sheet shrinks in size.

Unryu washi, also known as unryushi, has large pieces of partially beaten fibers included for texture, which create a floating cloud-like effect. Sometimes, patterned screens are raised through the vat of fibers and then applied to plain sheets of washi; these elements often resemble a “fiber-optic” effect, catching light in beautiful patterns of shimmering silkiness.

Suminagashi, meaning flowing ink, is marbled washi made by floating colored swirls of inks on water. As the washi is carefully laid on the ink swirls, the color is taken up into the washi, which is then dried. These delicate pastel patterns form pleasing, serendipitous designs.

USES FOR WASHI

Washi can be used for nearly everything, but, before you begin a project, consider the following historical perspective.

Ceremonial Use and Formal Documents

Probably the oldest use for washi is for special ceremonial use and for formal documents. Even today, the paper used for treaties, certificates, and important awards is often made with special fibers and careful processes, because it is expected to last for many generations.

Writing and Calligraphy

Writing and calligraphy are arts that demand papers of the finest qualities for permanence and elegance. In particular, shodo, Japanese brush calligraphy, requires specific qualities of paper to properly handle the style of inks used. The washi chosen should give the calligraphy life, working in concert with it, rather than becoming subjected by the forms of the calligraphic characters. There must be balance, and strong calligraphy requires more “white space” to give it room to breathe. With washi, that “white space” becomes an integral element of the piece, and not just emptiness.

Shoji Screens

The shoji screen is much more than a room partition or divider. For the Japanese, it organizes life itself into pleasant, illuminated, harmonious spaces. These versatile paper walls were originally erected as stand-alone structures, but later they were made to easily slide open or closed, quickly and efficiently converting space as more or less was needed. Shadows and sounds play on the screen’s panels to enhance the mood of the space. Washi used for shoji screens is particularly clean and strong. After several months to a year, it is repaired or replaced, much as westerners spruce up their rooms with a new coat of paint. Simply hanging beautiful pieces of washi in windows with less than picturesque views is something that all of us can do to enjoy its qualities in the daylight.

Containers and Wrappings

The act of giving has been raised to an art form in Japan, similar to the elaborate process of the Japanese tea ceremony, with important symbolism associated with every element. It is common even for small items to be packaged with at least two, and often several, levels of containment, enhancing both the experience of receiving, as well as that of giving. This is why washi is commonly used to cover or make containers. The pleasing, often bright colors and patterns generate remarks of appreciation, leading to prolonged conversation during this important, gift-giving process. Often, the pattern or style of the paper container will contain a clue as to the contents. Usually it is simply beautiful, and somehow appropriate to the occasion or to the recipient. Washi containers such as boxes and vases are often used over and over again.

Impatient children today often tear through gift wrap before seeing anything except the size of the package, but in Japan, it is customary to politely savor the attractiveness of each level of wrapping around even the most humble of gifts or treats. Indeed, we have saved most of the washi wrappings and containers from the gifts we have received. These papers find new reincarnations as thank-you notes, folded ornaments, greeting cards, or cherished components of entries in our travel scrapbooks. Passing these beautiful papers on provides a simple way to establish a continuity for the relationship through the years.

Books

People love one-of-a-kind, handmade books, which seem to go through cycles of fashion. Books featuring unique, handmade papers are especially popular now. Many of our customers come looking for archival and decorative papers to complement their latest book-binding project. This has been one of the more popular projects using paper, because it is not difficult or expensive, and customized or personalized books always make great gifts.

Maybe you have found the perfect washi for a gift scrapbook. Maybe you want to print your own great novel, then lovingly bind it in handmade paper for casual display on your own (or perhaps your mother’s) coffee table. Here is an opportunity for you to self-publish an heirloom!

Works of Art

Many of the customers who purchase our handmade papers are artists who appreciate painting, contact printing, or incorporating handmade papers into multimedia art. Abstract artists compose overlapping fields and shapes of different types of washi into collages of handmade paper. The art of composing torn bits of washi is a time-honored art called chigiri-e, or “torn paper pictures.” In this art, different colors and textures of torn washi create collages of still life and scenery, similar to watercolors, yet composed entirely of handmade papers with no applied paints or inks. In sumi-e, Japanese ink painting, the strength of the brushstrokes, the line and form of the drawing, and the subtle gestures are enhanced by the way the specially-designed washi paper’s fibers handle ink. Many types of washi take watercolors beautifully.

Lanterns

Famous artists and origami experts have made careers of illuminating washi. The warmth of the fiber sheets, the irregular clumps, knots, and deckle edges capture light in magical ways. Washi is naturally light and airy. When illuminated globes or other forms are suspended, they may evoke the moon and stars. With proper safeguarding, a washi lantern may be the best way to appreciate the various forms and types of handmade paper.