Читать книгу Advanced Origami - Michael G. LaFosse - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

ADVANCES IN ORIGAMI

The history of origami, or paperfolding, is widely recounted in books. What is not often said is that origami art is a relatively modern medium. It is, indeed, a more modern form of art than painting, music, sculpture or any other classical medium of artistic expression that comes to mind. It is so recent, in fact, that only in the last century has origami become a truly creative and expressive medium for both decorative and artistic purposes.

Initially, origami designs were passed from one generation to another. Today, advances in publishing, travel and electronic communications have aided and sped up the sharing of technical and artistic ideas in origami. With the aid of printing, photographs, video, DVD and computers, origami designs are no longer limited by the memory of the teacher and modern designs have become increasingly more complex.

Wilbur (the Piglet) was folded “freestyle” from a single 12-inch (30.5-cm) square of handmade cotton-abaca blend paper. Michael was so taken by a live piglet trotting across its pen while on display at the Topsfield Fair that he produced numerous gesture sketches, and even made special “pigskin paper” for this model. He also adopted an uncharacteristically loose folding style to capture the piglet’s happy spirit.

These new tools have also allowed the origami community to overcome certain technical problems in paperfolding. Since many origami artists consider the use of cutting and pasting to be cheating, these techniques are not encouraged. Through the concerted efforts of the origami community, the technical problems of creating models of any complexity with folding only—no cuts—has been resolved. After half a century of development, these technical challenges have melted away. Now it seems that there is no subject that cannot be rendered without cuts.

Just as origami designs have evolved, so has origami paper. Once limited in variety of color and pattern, commercial origami paper easily met the limited needs of the hobbyist’s predictable repertoire. Nowadays, hundreds of varieties of origami papers are available in a wide range of colors, patterns, textures, thicknesses and sizes. This reflects a greater demand for ready-to-use papers that are better suited to the vast new collections of origami projects published every year. This is certainly a welcome boon to the hobby. However, origami papers are still totally unsuitable for many of today’s complex and super complex origami designs. There are relatively few origami artists folding at this higher level, and such advanced projects require paper with more finely defined qualities. The papers that we have been able to produce have enabled other designers to push paperfolding technology to extreme limits. The designs of Robert Lang, Satoshi Kamiya, Daniel Robinson and others have, in turn, led us to produce papers that are even thinner and stronger. This co-evolution of designs and materials is likely to continue in exciting, unforeseen ways.

We can now fold origami creations with acid-free papers, made from high-quality fiber, which can last for generations with minimal care. And with present-day hand papermaking techniques, you can make your own incredibly strong acid-free paper of any desired size and thickness, colored specifically for whatever design you can imagine.

Many advanced models are folded with methods that are not easily shown in diagrams, resulting in origami publications on video and DVD. Other advanced works are often depicted only as crease patterns with a photo of the final model, rather than individual step-by-step drawings, since most people are simply curious about the method and only accomplished folders ever attempt to fold them. The basic fold (or base) for Wilbur (the Piglet) is actually quite simple, as shown in this crease pattern. The trick with any origami model is to breathe life into the subject with a loose, lyrical handling of the final shaping that only wet-folding allows.

This convergence of technological advances in making strong, thin archival paper with the advanced computer and information tools for sophisticated origami design has resulted in truly amazing works of folded paper art. This is, indeed, the golden age of origami art, since many of the best artists of this genre are still alive today. Most have practiced their art within the last few decades, and this explosion of documented origami designs is now evident in print as well as on the Internet, where a search of the word “origami” yields thousands of offerings.

ORIGAMI AS AN ART FORM

The many advances in the technology of origami design and paper have enabled the origami community to focus on origami as a form of art.

Origami’s methodology is significantly different from most other sculptural processes. Carving (in wood, stone, ice, glass or plastic) is subtractive: material is removed to reveal the final form. Building (from sand, clay, metal, wood, plastic, glass or paper) is additive: materials are brought together to produce the final sculpture. Single-sheet origami is metamorphic: nothing is subtracted or added.

Origami is engineering, and every piece of origami represents a puzzle to those who have never seen anything like it before. Because of this, viewers ask, “How was this done?” But some origami sculptures manage to go beyond this surface reaction to convey a deeper message to the viewer. In these works, the artist’s touch and vision are clearly evident. Like any work of art, these pieces are a rare treasure and the viewer will not be so concerned with how it was accomplished. This is what I strive for in my own work, and what I enjoy most in the best works of my peers.

Objects created with the intention of artistic expression are works of art. Whether they are judged good, great or otherwise depends on the audience. The choice of the medium does not determine the success of the art. Not all oil paintings are great art even though many great paintings are oils. An artist may use whatever materials and techniques are available. Just as my life was changed when I saw the origami self-portrait of Akira Yoshizawa, others are being influenced by origami art that speaks to them. Art begets artists. The more that origami art is shown, the more others explore and experience the power of that art.

This is the base that results from the crease pattern from which Wilbur (the Piglet) was folded.

ABOUT MY ORIGAMI DESIGNS

My origami designs can be attributed to a few different influences. The first of these derives from my training as a biologist, which has given me unusual opportunities to observe and study certain creatures in great detail. Initially, I am curious about the creature and try to understand it completely—its physical form, typical stances or postures, life cycle, behavior, even its individual personality. Eventually, I must admit that I shamelessly fall in love with my subjects so that I want to show others what I see by folding fairly realistic renditions of them.

Many of my designs are based on living creatures. My most recent popular design is a simple cardinal. There are no complex techniques, nor are there curved creases. The folding is straightforward and totally landmarked (in origami, a “landmark” is a physical reference point, such as a corner, edge, crease line or crossing point of several creases, which can be used to aid in the placement of the paper during the folding process). I am fortunate to have several cardinals around my house and their personality, song and behavior have always thrilled me. I am also lucky that the side profile of the cardinal is so easily translated into a simple origami model. It does not have to be wet-folded and you do not need special handmade paper. The typical 6- or 10-inch (15- or 25-cm) red/black duo origami paper is a perfect size range for these birds, and they make great ornaments for holiday trees and wreaths. Since, for the average folder, this is perhaps the most doable of all of my designs, the diagrams for this model appear at the beginning of the projects section. It is also one of the designs that I enjoy every time I fold it. I know each one will come out perfectly.

My designs are also influenced by my joy in the process of creating my art. I have reached a point where I enjoy continually exploring and refining a small number of designs, just as I enjoy playing the same composition again and again on the flute. From decades of experience, I can develop a folding sequence in my head, and then confirm the design by actually folding a piece of paper in my hands. I realized early that by simply folding a square piece of paper, I could make any shape, but making it elegant is the difficult part. Sometimes an origami koi emerges as a more successful model than the last one. Sometimes it might not be quite as successful in some respects. Nevertheless, it always comes out as a completely different individual.

Finally, as much as I enjoy the process of creating origami, I also like to share my art with others. To do this I co-founded the Origamido Studio with my partner Richard Alexander. This space allows us to dedicate ourselves to the art of origami. Origamido means “the way, through paperfolding,” a word I coined to remind me that my best creations have come from goal-inspired journeys. At our Origamido Studio we hold origami workshops, design and create origami models, make our own origami paper and showcase our origami art. We also operated galleries in three different public spaces from 1996 through 2011. I take great pride in knowing that the creatures I fold will be proudly displayed in their new homes. My pieces are now found all over the world, admired and perhaps even loved as much as they were when I made them.

These two images illustrate how I conjure up the gesture for the final work using other artistic mediums for practice while studying the subject in its natural habitat.

Strombus gallus III Back View. I dreamt of finding a huge strombus on the beach. Unfortunately, Mother Nature only allows these to reach a length of about 6 inches (15 cm), so I had to make my own. I began this piece with a wax version, then made a silicone mold, which allowed me to cast a white handmade paper pulp core or armature. It took nearly two years for me to apply about 500 lay-ups (a “lay-up” is a trade term for building up a form by applying layer after layer of material) of hand-made papier mâché as I grew this shell. The gesso has plenty of calcium carbonate to stiffen the paper, since I wanted to carve through the various colored layers of paper to produce subtle stripes. The outer surface has been rubbed with paste wax.

ABOUT THIS BOOK

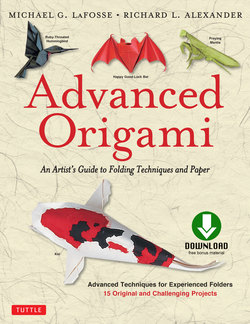

This book is primarily for origami artists who seek a higher quality in their work. Whether you are creating simple or complex models, paper choice, preparation, style and technique are all crucial to the final product. These decisions will set your work apart and make your experience more satisfying. The models that I have presented require using advanced folding techniques. These techniques, such as wet-folding, are essential to creating more lifelike origami models. I also have included directions for making your own origami paper, which is so important to creating not only incredible looking models but also models that last. While there are no shortcuts, the lessons that I have learned and now present here will act as a compass for your journey.

I have chosen fifteen projects from my original designs that I believe represent the richest journeys of my origami career. These pieces led me on a path of learning, discovery and personal and spiritual growth, and have renewed my sense of wonder. Each project is folded from a single sheet of paper without cutting. Most of these subjects are the common creatures that live in local woods and fields, and you will probably find the most satisfying results while folding subjects that you, too, can study in person.

These projects may be challenging technically, artistically or both. Each project is best mastered in stages. First is the study phase, when you become familiar with the subject and learn how to fold the model. At this stage, direct observation of the living subject is valuable. Good photos or video will help. This is also when you determine if you will modify any of the prescribed folding methods. You must discover which folding steps will cause you difficulties and how you will overcome them. Practice this with ordinary materials and without wetting the paper.

Next is the rehearsal stage. Strive to master all the technicalities and try to memorize the folding sequence. To do your best work, you must become totally comfortable with the entire folding method, even if you rely upon the diagrams, sight reading as you fold. If not, you may be overwhelmed by technicalities, distracting your full attention from the performance. During this stage of preparation, you should practice with the paper that you will use for the final sculpture. Each kind of paper has its own advantages, which you will learn about only if you routinely work with it. You may have to experiment with various kinds of paper to determine the most suitable.

Strombus gallus III Front View. This view captures my lifelong love affair with the interesting and sensuous forms of mollusks. The possibilities of paper are indeed endless.

Finally comes the performance stage, where your repeated rehearsals pay off. Here you will create your finest examples as your powers have grown to produce masterful and inspiring examples. How long will this take, days, months or years? Each person is different and each project has its unique demands. The real value lies in the journey, and the quality of your experience will be evident. Be patient and your efforts will be rewarded with success.