Читать книгу Planes for Brains - Michael G. LaFosse - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPaper Airplane Fun

By Richard Alexander

Finding an elegant origami design is a pleasure. Unlimited possibilities make for great fun!

We love to say that origami (paper folding) comes in many flavors, and every folder seems to have their favorite: greeting cards, animals, boxes, ornaments, jewelry, peace cranes, or dollar bill folds. There is one origami activity that rivals all of these in popularity: the folded paper airplane, perhaps the most satisfying origami flavor of all.

There are many reasons for this: Folding airplanes is fun for any age whether you explore folding alone, with a friend, in teams, or as a family. There is little cost and lots of action. For youngsters, it helps develop many skills and manual dexterity. There may be no better way for them to learn firsthand about cause and effect. Any number of ideas can be quickly conceived, folded, and flight-tested. Learning to apply the discipline of the scientific process can help a folder become more efficient with exploring new designs. Learning new designs challenges your memory. Folding and flying paper airplanes is a pastime you can enjoy for your entire lifetime. Best of all, it is one of the few origami activities that involve getting exercise and enjoying the great outdoors.

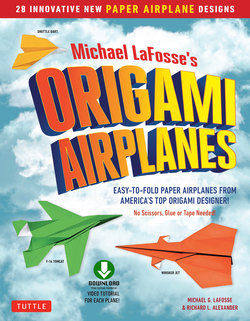

There are two major classes of paper airplanes: the largest group may involve some folding, but also includes assembly from cut-out or punched-out pieces of paper or card, often with slots and tabs, and many require attachments such as tape, glue, or other fasteners. This book is about having fun with the other major class: true origami airplanes folded from a single piece of paper with no cutting, tape, or appliances.

It’s a magical experience to transform a handy scrap of paper into a fully functional, soaring sculpture. Whether admired for their bold or graceful lines, superior performance, or amazing acrobatics, a few designs exude a personality of their own. Paper airplane enthusiasts love to share their favorite folding methods, critique each design’s looks, and prove the performance of their latest and greatest designs in friendly—but often intense—head-to-head contests.

Perhaps the most famous competition was the “First International Paper Airplane Competition” announced by the Scientific American magazine, in 1966. A young Michael LaFosse in Fitchburg, Massachusetts poured over his copy of the Simon and Schuster publication about the event, and, while initially excited by the brains and brouhaha surrounding the contest, he was largely surprised and disappointed by the relatively primitive level of folding technology. Given the state of the art in other origami publications by Randlett, Harbin and Honda, did these origami experts not know about the competition? Perhaps, he thought, there must have been many elegant purely origami entries that just did not fly well enough to qualify. He realized that his own paper airplane repertoire was rather mundane, and began to invest more time developing better origami airplane designs.

Since the early 1970s, Michael LaFosse has been hooked on designing pure origami models, and one of his goals soon became clear: To design interesting, elegant planes that flew well and had reliable landmarks for foolproof folding. The best of these have become his favorite designs, all of which are included in this book.

LaFosse published his first “Aero-gami F-14 Tomcat” design as a pamphlet in 1984, and he placed an ad in the back of the Popular Science magazine to sell copies. He also coined the term “Aero-gami” in 1984 for this origami F-14 venture, and he defined it to mean single-sheet, folding only. The origami F-14 Tomcat design quickly became a favorite on Air Force and Naval bases, as well as on engineering college campuses. It looked great, was fun to fold, and flew straight and fast. This design raised eyebrows, and even fighter pilots were impressed with the model and Michael’s unusual folding techniques. Similarly, his Art-Deco Wing was so unusual for its time that authors of other origami paper airplane books obtained his permission to publish his innovative designs in their publications—Wings & Th ings: Origami that Flies, by Stephen Weiss (1984, St. Martin’s Press); newsletters such as Fly Paper, by Charles Peck (1988) and in high tech magazines.

I was swept up in the ultralight aircraft mania of the early 1980’s, and fell in love with a one-person, fully retractable, amphibious, fiberglass composite kit called the Diehl Aero-Nautical XTC Cross Terrain Craft. I became a dealer, bought and sold some kits, and built one as an experimental aircraft. This gave me hundreds of hours with pilots, in and around cool warbirds and experimental airplanes at shows, fly-ins, and at several Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) chapter meetings.

I find folding from diagrams to be frustrating, and I am not alone. Even some college-educated engineers struggle with drawings of complex origami aircraft. Many paper airplane enthusiasts are quite young, and not yet skilled at using technical diagrams, so for them, most origami models are much easier to fold from video instructions. In 1992, we recorded Michael folding his F-14 Tomcat and gave the clip to a neighbor. By using the pause and replay buttons on his video deck, the eight-year-old successfully folded and flew his F-14. This encouraged us to record more of Michael’s designs, which allowed us to self-publish a video, “Planes for Brains.” A few years later, we followed up with more of his airplanes folded from rectangular office bond (8½ by 11-inch US letter paper) on our video called “Aerogami.” We made many of these video lessons available to the public through a pay-per-view website, and then took them to cable TV on Comcast’s On Demand “Activity TV” series, as well as on the Internet (www.activityTV.com).

Michael has been sharing his designs with many people over the years, and we enjoy meeting them at paper airplane contests and origami conventions. In August, 1999, Michael and I had the opportunity to drive across the USA—from Boston to Seattle—to attend the Origami Regional Conference of America, or “ORCA.” One of the younger attendees, named Simon Berry, saw that I was recording video footage of folders explaining their creations, and he volunteered to show me a special, “hybrid” paper airplane he had created. It looked somewhat familiar, and so I asked him how he designed it. Come to find out, a good friend of ours had loaned him Michael LaFosse’s first paper airplane video, and Simon had combined elements of Michael’s Chuck Finn (see page 26), and the Art-Deco Wing (see page 30). I asked, “What do you call it?” “Simon’s Plane!” was his proud reply!

If you love paper airplanes, fold your way through this book, try some of your own modifications, or inject some of Michael’s ideas into your original designs. Buy some copies for your friends, and then invite them over for a paper airplane contest cookout in your backyard to see what they’ve discovered. These friendly competitions increase design expectations and raise the bar for performance. Be prepared for more awesome designs at each subsequent meeting. Friendly competition might even spread to your friends’ friends, and can even inspire an entire community.

Now, strap yourself in, because here we go!

A sleek Nifty Fifty awaits its maiden voyage.