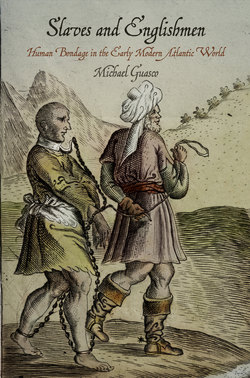

Читать книгу Slaves and Englishmen - Michael Guasco - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

______________

Slaves the World Over: Early English Encounters with Slavery

England stepped purposely onto the global stage during the second half of the sixteenth century as its merchants, sailors, emigrants, bureaucrats, and adventurers fanned out across the globe in search of new lands, new trade routes, and new commodities. The English had not been well represented among the first wave of Europeans who pushed out into the Atlantic world during the early stages of long-distance navigation and global exploration during the late fifteenth century. That, however, changed dramatically during the Elizabethan era. In the opening pages of the 1589 edition of his Principall Navigations, Richard Hakluyt boasted that “in searching the most opposite corners and quarters of the world” and “in compassing the vaste globe of the earth more than once,” the English “have excelled all the nations and people of her earth.”1 If Hakluyt’s patriotism inclined him to overstate the case, little doubt remained about the rapidly escalating English interest in the affairs of the world. Even if they stayed at home, where they might discover many of the same new worlds in published accounts or witness foreign lands and strange peoples on stage or experience rare and unusual items as consumers, countless Englishmen were beginning to see themselves as part of an expanding and diverse world in motion. But as much as English eyes were captivated, in the words of Richard Willes in 1577, by “the different manners & fashions of divers nations, the wonderfull workes of nature, the sightes of straunge trees, fruites, foule, and beastes, [and] the infinite treasure of Pearle, Golde, [and] Silver,” the English had reasons to be cautious.2 As more wary observers were quick to recognize, the world beyond England’s shores promised great rewards, but the potential dangers were many. Not least among these was slavery, a subject that never ceased to impress English authors and publishers or, apparently, simultaneously fascinate and horrify English readers.

It would have been difficult for perceptive travelers and careful readers in the early modern era to avoid the conclusion that slavery was a universal institution. Many works that appeared in print during the late Tudor and early Stuart eras spoke to the subject in a rather matter-of-fact fashion. When Jean Bodin’s Six Books of a Commonweale appeared in English in 1606, many Englishmen were already aware of the writings of the French jurist from the Latin and French editions of his previous works. Bodin treated slavery as a widespread human institution that began “immediately after the general deluge” before it diminished for a time but was “now againe approved, by the agreement and consent of almost all nations.” Regardless of religious or governmental considerations, slavery existed everywhere. From the West Indies, whose people “never heard speech of the lawes of God or man” to places characterized by greater degrees of civility or where Europeans expected to find “the holiest men that ever lived,” slaves were ubiquitous. Like many of his contemporaries, Bodin concluded that human bondage—in all its possible manifestations—was the likely condition of a majority of the world’s peoples. Of course, this depiction shocked no one in England, many of whom claimed that they lived in a land largely untouched by slavery even as they recognized that their situation was exceptional in that regard.3

Similar conclusions could be gleaned from another French author, Pierre Charron, whose treatise Of Wisdom was translated into English by Samson Lennard in the early seventeenth century (and subsequently reprinted eight other times before 1700). Charron declared that “the use of slaves … is a thing both monstrous and ignominious in the nature of man.” Charron noted that the “law of Moyses hath permitted this as other things, … but not such as hath beene elsewhere: for it was neither so great, nor so absolute, nor perpetuall, but moderated within the compasse of seven yeeres at the most.” Charron recognized, as most Englishmen did also, that different types of slavery existed, but that, in essence, slaves “have no power neither in their bodies nor their goods, but are wholly their masters, who may give, lend, sell, resell, exchange, and use them as beasts of services.”4 From the perspective of the enslaved, human bondage must have seemed completely arbitrary, involving as it did the total loss of self-determination, dehumanization, and emasculation. From a comfortable remove, however, slavery was more unfortunate than tragic, a comprehensible institution if only because it was so common.

But the English did not need the French to tell them about slavery. English authors were equally capable of lamenting the continued presence of human bondage and the plight of the enslaved. Slavery’s pervasiveness could easily be gleaned from some of the more important geographical and historical works of the day, especially the multivolume collections issued by Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas between the 1580s and 1620s. Hakluyt and Purchas sought to celebrate past English achievements and ongoing overseas activities, as well as to promote English expansionism. There were, however, important differences between Hakluyt’s late sixteenth-century volumes (1582, 1589, and 1598–1600) and the even more extensive collections published by Purchas a generation later (1613, 1614, 1617, and 1625). Hakluyt devoted himself to memorializing English accomplishments and urged his countrymen to pursue evermore distant and potentially profitable voyages of discovery. He was particularly excited about the potential wealth that might be drawn from American enterprises, although the future development of large-scale plantations was arguably less important in his publications than the broader themes of commerce, exploration, and English national greatness.5 Purchas borrowed from and extended Hakluyt’s scholarly enterprise, but his selections and emendations indicate that he was both a less discriminating editor and more beholden to a particularly overweening theological perspective. Protestant providencialism, perhaps even more than any sense of English patriotism, weighed heavily on Purchas’s otherwise richly detailed and varied collections and they are not necessarily the better for it.6

Regardless of their differences, Hakluyt and Purchas presented material that revealed the depth and breadth of slavery throughout the world. Indeed, in the opening pages of his Hakluytus Posthumus, or, Purchas His Pilgrimes, printed in four large volumes in 1625, Purchas reflected on the subject of bondage in religious, philosophical, and historical terms. “Christians,” he noted as a kind of operating premise to his larger work, “are not their own.” “Hee then that is Christs, is a new Creature, to which, bondage or freedome and other worldly respects, are meere respects and circumstances.” Slavery, at least as far as the Anglican cleric Samuel Purchas would have it, needed to be understood in metaphysical terms before it could be fully appreciated as a physical condition or secular institution that bore down upon the nameless and numberless masses. Englishmen needed to appreciate their indebtedness to God—“[H]ee that denieth himselfe and his owne will, puts off the chaines of his bondage, the slavery to innumerable tyrants, [and] impious lusts”—before they could come to terms with the worldly slavery endured by so many individuals and nations.7 Whether they did as Purchas asked, however, Englishmen encountered slavery wherever they traveled, used its presence to shape their conception of newfound peoples and places, and continued to think more carefully about how—as Englishmen—they were unique in their national antipathy for human bondage.

* * *

If slavery was a global phenomenon, the English did not have to travel far to find it. On the European continent, particularly in those lands that bordered the Mediterranean, slavery was a vital institution, largely as a result of internecine conflict between the Christian powers and Islam. Slavery had largely disappeared as an institution of any significant cultural or economic importance in northern Europe during the medieval era. To the south, however, slavery persisted. In Italy, large numbers of Russians, Slavs, Greeks, and Muslims were held in bondage, but sub-Saharan Africans could also be found in increasing numbers among the enslaved. European slaves from the Black Sea and Balkan regions were less common on the Iberian Peninsula, but large numbers of captured Muslims and prisoners-of-war from other parts of the Mediterranean world filled the ranks of the unfree. In both places, the pattern was much the same: An array of people, regardless of their physical appearance or religion, could be found in bondage. After the fourteenth century, non-European and largely non-Christian slaves were increasingly prevalent as physical appearance and religion began to serve as more absolute indicators of an individual’s legal status. The rise of sub-Saharan African slaves was particularly important. In places where the Reconquista had been achieved, as in Portugal, European buyers acquired Africans through peaceful trade networks that linked southern Europe to a vibrant and extensive trans-Saharan market. By the first decade of the sixteenth century, even the recently recaptured city of Granada, once the center of Moorish civilization on the Iberian peninsula, engaged in a slave trade that was two-thirds black.8

But if slavery was common in southern Europe, that reality could have been missed by Englishmen who were often looking elsewhere during the early Elizabethan era. English privateers and pirates coursed Mediterranean waters in small numbers, but escalating tensions between Protestant England and the Catholic powers made it difficult for English merchants and mariners to ply their trade in the region, at least before 1580. The English government and merchant community did, however, cast about other regions in search of profitable trade and in the process a handful of travelers came face-to-face with human bondage. English engagement with Russia, to pick an early example, brought the subject of continental slavery close to home, not least because it was the previously noted plight of a Russian slave that prompted the Star Chamber in 1567 to declare that England was “too pure an air for slaves to breathe in.” Russia, in and of itself, interested most Englishmen to a limited degree, but of more interest was its value as a highway to places that really sparkled in the imagination of those people who dreamed of wealth and power. Much as early Portuguese awareness of and involvement in the African slave trade was a by-product of Portugal’s effort to circumvent Africa, the search for a northeast passage to the Indies at mid-century and curiosity about alternate routes to Persia led to the creation of the Muscovy Company in 1555. The Muscovy Company dispatched ships annually to Russia and controlled English trade to the Middle East for about a generation, sending out six separate expeditions to Persia via the northern route in search of valuable silks and spices before the Ottoman Turks curtailed the trade in 1580.9 Russia, therefore, provided one of the earliest opportunities for the English to witness and write about slavery as it was practiced in contemporary settings.

Human bondage was an inescapable reality in the Russian environs described so vividly by the early trader Anthony Jenkinson, who made his first trip to the region in 1557, and Giles Fletcher, who was sent to Russia as a special ambassador in 1588.10 Both Jenkinson and Fletcher located the hub of slavery in the central Asian regions on the southern border of Russia. There, Jenkinson observed, slavery manifested itself prominently in the form of concubinage. Jenkinson even attributed some of the internal turmoil he witnessed to the absence of “natural love among them, by reason that they are begotten of divers women, and commonly they are the children of slaves.” Slavery was so common in Bokhara that merchants from India and Persia attended the famous bazaars, in part, to purchase Christian slaves. Even Jenkinson came away with some slaves. When he boarded a ship on the Caspian Sea for his return trip to Moscow, he had with him “25. Russes, which had been slaves a long time in Tartaria, nor ever had before my comming, libertie, or meanes to gette home, and these slaves served to rowe when neede was.” Upon reaching Moscow in late 1559, he demonstrated his willingness to participate in the indigenous system of bondage and exchange by presenting some of his slaves to the Tsar as a sign of his gratitude for the favors bestowed on English traders.11

Giles Fletcher’s travels were not nearly as wide-ranging as those of Jenkinson, but he also provided an insightful picture of human bondage in sixteenth-century Russia. Indeed, Russian slavery may have been relatively easy for Fletcher to grasp, involving as it did categories familiar in contemporary English discourse on the subject. Fletcher was deeply interested in the plight of “the poor people that are now oppressed with intollerable servitude,” such that “people for the most part … wishe for some forreine invasion, which they suppose to bee the onely meanes, to rid them of the heavy yoke of this tyrannous government.” Everyone, in Fletcher’s mind, suffered from an absence of political liberty, but he believed “that there is no servant nor bondslave more awed by his Maister, nor kept downe in more servile subjection, then the poore people are.” In his description of “Novograde,” Fletcher elaborated on the situation of Scythian slaves who had rebelled but were then subsequently put down by their masters with nothing more than horsewhips “to put them in remembrance of their servile condition, thereby to terrifie them, & abate their courage.” Continuing to emphasize the parallels between slaves and animals, Fletcher recounted how the chastened slaves “fled altogether like sheepe before the drivers.”12 Outside Russia proper, Fletcher characterized the Tartars, or Mongols, in even less flattering terms as a people who engaged in more extensive forms of human bondage. Fletcher claimed that the “chiefe bootie the Tartars seeke for in all their warres, is to get store of captives, specially yong boyes, and girls, whom they sell to the Turkes, or other their neighbors.” These eastern slave raiders, however, had little patience or compassion for their victims, such that if any of their captives “happen to tyer, or to be sicke on the way, they dash him against the ground, or some tree, and so leave him dead.”13

English governmental affairs and commercial interests inspired curiosity about Russia and the reports of English merchants, including what they had to say about slavery, indicate that even though Russia was located nearby (at least on a global scale), geographic proximity had little bearing on cultural similarity. Russians were different and their active embrace of slavery was a clear indication of that difference. This point was made even more baldly when the English turned their attention to Ireland. Tudor and Stuart Englishmen thought and wrote about Ireland a great deal, arguably more than any other place in the world in the early modern era.14 When they did so, they rarely had nice things to say. Collectively, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland constituted the English marchlands during the early modern era. Beginning in the eleventh century, the Norman kings inaugurated what turned out to be a protracted, grinding effort to subdue these territories and their inhabitants under Anglo-Norman rule. Medieval Scotland and Wales were less unified nations than ill-defined regions consisting of multiple hotly contested principalities and fiefdoms whose inhabitants posed a serious threat to their English neighbors. During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, Scots repeatedly invaded northern England. As a result, the English chronicler Symeon of Durham lamented, “Scotland was filled with English slaves.” The invasion of 1138, John of Hexam detailed, led to the death of countless men while “the maidens and widows, naked, bound with ropes, were driven off to Scotland in crowds to the yoke of slavery.”15 The attempt by King Edward I, and other English monarchs, to subdue the Scots was partly an effort to extend English sovereignty, but English incursions were also designed to eliminate slave raiding on the northern frontier.

The situation in Ireland was different. Most Englishmen subscribed to long-held and deeply embedded derogatory ideas about the Irish people, ideas that often drew directly on the foundational writing of Gerald of Wales, the twelfth-century chronicler who had journeyed to Ireland in 1185 with an Anglo-Norman force led by the future King John. Gerald’s scurrilous characterizations were the rhetorical armament of an invading army, but they proved long-lasting and his observations were translated into English and reprinted, or echoed, throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.16 In Gerald’s telling, the Irish were naked, wild, and unfriendly people who had more in common with animals than with men. Or, in the unguarded words of Andrew Trollope in a letter to Francis Walsingham written in 1581, the Irish “are not christian, civil human creatures, but heathen or rather savages and brute beasts” who “go commonly all naked.” Clearly intent on making sure Walsingham did not miss the point, Trollope added that “[i]f hell were open and all the evil spirits abroad, they could never be worse than these Irish rogues—rather dogs or worse than dogs.” Or, most famously, in Edmund Spenser’s telling, the Irish “steal; they are cruel and bloody, full of revenge and delighting in deadly execution, licentious swearers and blasphemers, common ravishers of women and murderers of children.”17

Of course, English observers routinely heaped scorn on all sorts of people throughout the world, but the Irish were favored targets because foreign observers could easily compare them with the English. Unlike the people and societies that might be found throughout the Mediterranean world, Asia, Africa, or the Americas, the only thing that separated the Irish from the English was a short stretch of easily navigable water. On the surface, as Barnabe Rich noted, “the English, Scottish, and Irish are easy to be discerned from all the nations of the world, besides as well by the excellency of their complexions as by all the rest of their lineaments, from the crown of the head, to the sole of the foot.” All the peoples of the British Isles were more alike than unlike and therefore the supposed barbarity of the Irish people and the rudeness of their customs were problems in need of explaining. How was it, Rich wondered, “that a countrey scituate and seated under so temperate a Climate” could be “more uncivill, more uncleanly, more barbarous, and more brutish … then any other part of the world that is knowne”?18 Colonialism needed to be justified, but who the Irish really were was an even bigger problem because that question could not be addressed without broaching the larger problem of what it meant to be English, a problem that confronted England repeatedly from the late medieval through the early modern era.19

Ireland therefore presented England with a series of overlapping social, political, and cultural challenges that were worked out over the course of many generations.20 Predictably, English commentators addressed the subject of slavery in Ireland, but they did so in curious ways during the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Although the English had been in Ireland since the late twelfth century, their control over the island was generally limited to the area around Dublin—the so-called Irish Pale—and often hotly contested. During the sixteenth century, a series of local rebellions took place that shaped English colonialism on the island. In the wake of Thomas Fitzgerald’s failed rebellion in 1534, Henry VIII recommitted the English government to imposing its sovereignty on the island, even having himself declared “king” rather than “lord” of Ireland in 1541. This effort met with stern resistance throughout the rest of the century, most famously during two large-scale conflicts: the Second Desmond Rebellion (1579–83), which sought to eject the English from Munster, and Tyrone’s Rebellion (1594–1603), led by the capable Hugh O’Neill, which spread outward from Ulster and nearly succeeded in defeating the English.21 The bloody effort to impose English rule in Ireland, and the refusal of both the Anglo-Irish and Gaelic Irish to be brought to heel, combined therefore to create a compelling rationale for English invaders to write about slavery.

Irish resistance to English suzerainty virtually demanded character assassination in order to justify the ongoing efforts to (re)conquer the island. Considering the ease with which English propagandists denigrated the Irish, it should come as no surprise that would-be English conquerors routinely justified the continuing effort to subdue the Irish by expressing their profound sympathy for “the country people living under the lords’ absolute power as slaves.” “[U]nder the sun,” Sir Philip Sidney concluded in the 1570s, “there is not a nation which live more tyrannously than they do, one over the other.” In 1567, English officials accused the rebellious Earl of Desmond of treating the inhabitants of Cork “as in effecte they are or were become his Thralls or Slaves.” In 1592, Sir Henry Bagenal reported to Lord Burghley that because the English had allowed the local lords to maintain control of large swaths of land, Irish leaders had “been enabled to enslave all their tenants” and maintain their independence from English rule. In an even more extensive treatment, Sir John Davies, who served in Ireland as Attorney-General and, eventually, Speaker of the Irish Parliament, claimed that the problem with the Irish was not their basic nature but that “such as are oppressed and live in slavery are ever put to their shifts.” Irish laws and traditions, and the oppressive rule and extortions of Irish lords, had simultaneously promoted tyranny from above and made “the tenant a very slave and villain, and in one respect more miserable than bondslaves, for commonly the bondslave is fed by his lord, but here the lord was fed by his bondslave.”22

Because early modern Englishmen were routinely critical of slavery as it existed throughout the world, these accusations are unsurprising. In Ireland, however, slavery provided English apologists with a weapon to claim that they were actually engaged in a war to liberate the mass of poor, downtrodden Irish from the bondage that was imposed on them by their own lords. They recognized, of course, that slavery was a double-edged rhetorical sword. Barnabe Rich argued that the Irish rebellions were routinely excused by people who claimed that they wanted “to free themselves from thralldom (as they pretended).” And, indeed, Rich was correct. Hugh O’Neill justified his efforts in 1598, in part, by lamenting that “we Irishmen are exiled and made bond slaves and servitors to a strange and foreign prince, having neither joy nor felicity in anything, remaining still in captivity.” But Ireland’s problem, according to Rich, was not really the Irish enslaving their own people or the English holding their neighbors in a state of bondage so much as it was the absence of the restraints on the inherent cruelty of the Irish. “[W]hat subjects in Europe do live so lawless as the Irish,” he queried, “when the lords and great men throughout the whole country do rather seem to be absolute than to live within the compass of subjection?” Bondage was relevant because Ireland lacked order, something that could only be rectified through the imposition of English rule.23

Ironically, although slavery may have been listed prominently among the reasons why the English needed to impose themselves on the Irish, it is a measure of the frustration of English proponents of the invasion of Ireland like Sir Arthur Chichester, writing to Burghley’s successor, Lord Cecil, in 1602, that they were led to conclude that “their barbarism gives us cause to think them unworthy of other treatment than to be made perpetual slaves to her Majesty.” Chichester, however, did not generate this recommendation without precedent. The idea that the Irish deserved to be enslaved had previously been mentioned by Gerald of Wales and it reappeared in print when Raphael Holinshed published his Chronicles in the 1570s, the second volume of which dealt largely with Ireland. Holinshed reported on a thirteenth-century gathering of clergymen in Ireland where the participants sought out an explanation for why Ireland “was thus plagued by the resort and repaire of strangers in among them.” After some debate, the congregants concluded that “it was Gods just plague for the sinnes of the people, and especiallie bicause they used to buie Englishmen of merchants and pirats, and (contrarie to all equitie or reason) did make bondslaves of them.” Divine justice “hath set these Englishmen & strangers to reduce them now into the like slaverie and bondage.” It was the sinful behavior of the Irish themselves, Holinshed’s Chronicles reported, that brought the Anglo-Norman invaders to their door. And God, not without a sense of irony, apparently meant for the Irish to be enslaved for retribution while “all the Englishmen within that land, wheresoever they were, in bondage or captivitie, should be manumissed, set free and at libertie.”24 Such was the nature of English ideas about slavery in the early modern era that the effort to rescue the Irish from slavery demanded that the Irish be reduced to slavery.

* * *

The presence of slavery in Russia and Ireland was important to English observers bent on emphasizing the differences between themselves and the inhabitants of other parts of Europe. It also proved to be an easy way to criticize the customary practices and cultural values of other nations. But slavery was not necessarily viewed as inherently bad or as an indicator of moral turpitude in all cases. Many Englishmen approached slavery with a kind of academic curiosity, not revulsion. The subtlety with which English travelers were willing to treat the subject of human bondage as it was practiced in foreign lands is demonstrated in the surviving accounts of the system of slavery that pervaded the Mediterranean world, especially Turkey, Syria, Persia, Jerusalem, the Levant, Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco (much of which was, in fact, part of the Ottoman Empire). Certainly, English writers like Samuel Purchas did not hesitate to emphasize that slavery was an abject, dehumanizing, and physically punishing system. In the introduction to his 1625 work, he asserted that “the Devill hath sent the Moores with damnable Mahumetisme in their merchandizing quite thorow the East, to pervert so many Nations with thraldome of their states and persons.”25 Slavery was spiritually symbolic in Purchas’s telling, but it was immediate and meaningful as an all-too-real fate suffered by countless individuals. But that was only part of the story.

Most of the English and other European travelers whose accounts were published by Hakluyt and Purchas (or separately printed) during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries were careful and often quite generous observers. Thus, diligent readers could learn a great deal about the particular characteristics of Mediterranean slavery and, when they were not bemoaning the plight of their own countrymen held in bondage (something that will be discussed more fully in Chapter 4), their observations could be quite instructive. From European witnesses, then, it was clear that there were aspects of human bondage as it functioned in the Mediterranean world that conformed to expectations. Slaves were, by definition, owned or in the possession of another power. Slaves in the Mediterranean also typically originated as prisoners of war and many of these captives were Christians from southern Europe. John Locke, who traveled to Jerusalem in 1553, wrote about a battle “a fewe yeeres past” in which the victorious Turks captured a fortress “from the Emperour, in which fight were slaine three hundred Spanish souldiers, besides the rest which were taken prisoners, and made gallie slaves.” George Sandys, who visited the Levant in 1610, reiterated a simple point when he noted that slaves were primarily “Christians taken in the Warres, or purchased with their money.”26 Indeed, English audiences were so familiar with this sort of observation by the seventeenth century that the point was rarely described in detail. Nothing could be less surprising than the presence of slaves who met their fate as a result of being on the losing side of a battle.

A number of subjects, however, either did not cohere with English expectations or were viewed as so fantastic that they were deemed worthy of fuller consideration. Military slavery, for example, elicited considerable attention as a distinctive form of slavery and as a peculiar practice located in one particular region of the world. English travelers in the Mediterranean world routinely commented on the large number of slave soldiers, or Janizaries, in the Ottoman Empire. The remarkably well-traveled Anthony Jenkinson, ultimately more famous for his exploits in Russia, described an elaborate procession “of Soliman the grand Turk” he witnessed into Syria in 1553 that included 16,000 Janizaries, “slaves of the Grand Signior.” On a much smaller scale, slave soldiers were also incidental characters. William Biddulph, an English cleric, noted in 1600 that a local English factor “provided us with horses to ride to Aleppo, and a Janizarie, called Paravan Bashaw … to guard us” on the dangerous three-day journey inland. Although Biddulph praised the assistance he received from this man, he later reported, while in the vicinity of Jerusalem, that the inhabitants of a village called Lacmine “fled into the Mountaynes to dwell, for feare of the Janizaries of Damascus, who travelling that way used to take from them … whatsoever things else they found in their homes.” Purchas registered his personal feelings about the subject at this juncture when he noted in the margin of this passage, simply, “Wretched slaverie.” He also more than likely agreed with Sir Anthony Sherley’s characterization from 1599 that “Janizaries (which were appointed for the safetie of the Provinces …) now obey no authoritie which calleth them to other Warres: but by combining themselves in a strength together, tyrannize the Countries committed to their charges.”27

English observers were particularly intrigued by military slaves because they wielded extraordinary power and influence. Yet, just as slaves could be found in privileged positions at the top of society, exercising their will through violence, other important English sources reveal that slavery could involve utter degradation, suffering, and poverty for individuals at the other end of the social ladder. In a discussion of charity among the Turks, George Sandys acknowledged that “I have seene but few Beggers amongst them. Yet sometimes you shall meet in the streets with couples chained together by the necke, who beg to satisfie their Creditors in part, and are at the yeeres end released of their Bonds, provided that they make satisfaction if they prove afterward able.” Purchas also published an account by Leo Africanus (often referred to in England as “John Leo” but born in Morocco as “al-Hasan al-Wazzan”) of Moroccans who found themselves pressed between the King of Portugal on one side and the King of Fez on the other. The resulting famine and scarcity brought the people “unto such misery, that they freely offered themselves as slaves” to the Portuguese, “submitting themselves to any man, that was willing to relieve their intolerable hunger.”28 If powerful slaves like the Janizaries of the Ottoman Empire were frightful, the condition of those who happened to lapse into a state of slavery as a result of debt or poverty, or perhaps even submitted to slavery voluntarily, was more lamentable than menacing.29

A slave’s chances in the world depended greatly on who owned him or her. All English travelers in the Islamic world commented on the heterogeneous nature of the local populations. William Biddulph noted that Aleppo was “inhabited by Turkes, Moores, Arabians, Jewes, Greekes, Armenians, Chelfalines, Nostranes, and people of sundry other Nations.” The enslaved population, however, was described more narrowly. Sandys claimed that slaves consisted primarily of Christians taken in war or those purchased with money at any of the weekly markets “where they are to be sold as Horses in Faires: the men being rated according to their faculties, or personal abilities, as the Women for their youths and beauties.” These slaves performed a number of services, but if they were fortunate enough to possess a useful skill, they might eventually be able to pay for their freedom. If they were exceptionally fortunate, Sandys added, they might be bought by a Christian. Thus, slaves at market “endeavour[ed] to allure the Christians to buy them, as expecting from them a more easie servitude, and continuance of Religion: when being thrall to the Turke, they are often inforced to renounce it for their better entertainment.” Regardless, Sandys suggested, quite accurately, there were well-established avenues to freedom under Islamic law. Sandys claimed that the “men-slaves may compell their Masters … to limit the time of their bondage, or set a price of their redemption, or else to sell them to another.” If slaves were owned by a Christian master and subsequently converted to Islam, “they are discharged of their bondage; but if a Slave of a Turke, he onely is the better intreated.” Those who ended up in the galleys, or in more menial tasks, seldom were released “in regard of their small number, and much employment which they have for them.”30 Slavery was an absolute condition, but there were still opportunities for manumission for the lucky few.

Some English observers were also clearly fascinated by the important role gender played in shaping the supply and use of slaves in the Islamic world. Gender influenced English impressions of contemporary slavery because, quite unlike in England, many roles prescribed for slaves in the Muslim world were conditioned by sex.31 Female slaves were most often depicted as concubines, or even wives. In 1574, Geffrey Ducket characterized “[b]ondmen and bondwomen [as] … one of the best kind of merchandise that any man may bring” to Persia. Ducket noted that when Persians purchased “any maydes or yong women, they use to feele them in all partes, as with us men doe horses.” Female slaves were the absolute servants of their masters and could be sold many times over. If these women were found by their masters “to be false to him, and give her body to any other, he may kill her if he will.” Not only Persians, but foreign merchants and travelers seem to have participated in the ownership of women. Ducket noted that when the visitors stayed for any length of time in one place, he “hireth a woman, or sometimes 2. or 3. during his abode there … for there they use to put out their women to hire, as wee doo here hackney horses.”32

Samuel Purchas published several accounts that characterized the role of enslaved women in a similar vein. Not surprisingly, George Sandys weighed in on the subject when he noted that every man could hold “as many Concubine slaves as hee is able to keepe, of what Religion soever.” From his general description of the lot of wives and concubines, Sandys concluded that he could “speake of their slaves: for little difference is there made between them.” While male slaves were “rated according to their faculties, or personal abilities,” women were valued “for their youths and beauties.” Once a woman was purchased, her buyer examined her for “assurance (if so she be said to be) of her virginitie.” Masters could then “lye with them, chastise them, exchange and sell them at their pleasure.” But Christian masters were not completely void of compassion, he claimed, for he “will not lightly sell her whom he hath layne with, but give her libertie.”33 Such were the benefits that apparently accrued to women whose fate it was to be purchased for the sexual favors they were compelled to provide for their owners.

As fascinating as the subject may have been, female slavery was something that historically minded Englishmen could easily comprehend. William of Malmesbury’s twelfth-century Chronicle recounted several examples from pre-Conquest society of the selling of female slaves out of England. Malmesbury recorded these tales as examples of the degeneracy of England before the arrival of the Normans. In one particularly offensive example, Malmesbury cited the custom, “repugnant to nature, which they adopted; namely, to sell their female servants, when pregnant by them and after they had satisfied their lust, either to public prostitution, or foreign slavery.” Likewise, in another tale, Malmesbury recounted how the sister of the early eleventh-century King Canute had been killed by a lightning strike, supposedly as punishment for the king making money off the “horrid traffic” in English youths, especially girls, who were taken against their will and sold into slavery in Denmark.34 The purchase of females had a particular symbolic power in England where, as in Islam, the significance of the enslavement of women was historically rooted in the owner’s ability to exploit women’s sexuality rather than the women’s labor value. In addition, the use of slave women could enhance the master’s power not only over slave men but also over free men because of their ability to control access to a desired commodity or destination. Male slaves never forgot that regardless of how they might define the nature of their relationship with a female slave, another man—a free male—actually exercised the ultimate authority. Within this historical context, readers needed little elaboration in the accounts printed by Hakluyt and Purchas to understand that female concubinage was an insidious form of slavery that was part and parcel of the overall interest of the male population in controlling the sexual behavior of women.35

The enslavement of women clearly fascinated English observers, but they were arguably even more intrigued, or perhaps repulsed, by the closely related subject of eunuchs, particularly in the Islamic world. Once again, the account by George Sandys is instructive. Sandys claimed that many of the children “that the Turkes doe buy … they castrate, making all smooth as the backe of the hand, (whereof divers doe dye in the cutting) who supply the uses of Nature with a Silver Quill, which they wear in their Turbants.” Sandys was fascinated that eunuchs were “heere in great repute with their Masters, trusted with their States, the Government of their Women and Houses in their absence; having for the most part beene approoved faithfull, wise, and couragious.” Robert Withers went into even greater detail in his account of the “Grand Signiors Serraglio” from 1620. Withers was struck in particular by the role played by black eunuchs, who “goe about and doe all other businesse for the Sultanaes in the Womens lodgings, which White Eunuches cannot performe.” And, in fact, black eunuchs do seem to have become especially prized possessions and influential allies by the sixteenth century in the Ottoman Empire.36

Eunuchs played a particularly prominent role in Purchas’s volumes because they were an especially visible sign of the degeneracy he believed inundated the Mediterranean world and much of the east. Eunuchs were not merely men who had been castrated; they were agents of sexual depravity. The Withers account, for example, was preceded on the printed page by the record of the English cleric Edward Terry, who journeyed to India in 1616 to serve as Sir Thomas Roe’s chaplain in the English Embassy. Like numerous other European witnesses, Terry mentioned eunuchs in passing as royal attendants, guards, and even high officials. But among his varied observations, Terry noted at one point that nobody lived “in the Kings house but his women and Eunuches, and some little Boyes which hee keepes about him for a wicked use.” At once, this comment reads as both a passing reference to the luxury in which a local ruler lived and a resounding condemnation of his detestable personal proclivities.37 Eunuchs repelled, then, not simply because they had been physically altered, but because they were emblematic of a widespread phenomenon that reflected a broader understanding of Islam, the exotic lands to the east, and slavery.

* * *

As Terry’s account implies, the English were quick to identify the Mediterranean as the epicenter of bondage and captivity in the world, but there were other newly encountered places that were easily characterized in like terms. The presence and roles of slaves in these less familiar, and decidedly less menacing, societies reinforced the familiar conventions that human bondage often resulted from warfare and represented a kind of perpetual captivity involving a complicated interplay between indiscriminate and potentially brutal treatment and generous opportunities for the enslaved either to exercise power through their bondage or to reclaim their lost liberty. These ideas, however, were often based on imperfect and incomplete information. Because few Englishmen traveled to either south or southeast Asia before 1600, Richard Hakluyt had little in the way of firsthand observations or written narrative accounts before he published the final edition of the Principal Navigations. Samuel Purchas, however, was able to extract liberally from a mixture of Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and English narratives and therefore included significantly more material on Asia in his volumes.38 The English sources were a particularly rich body of material that Purchas acquired directly from the English East India Company (EIC) in 1622. The EIC had been founded in 1600 and English ships and merchants began to show up in the southeast Asian archipelago soon thereafter. Before the EIC reformed in 1613 as a joint-stock company, at least twelve separate expeditions voyaged to the region. English ships also sailed to India in 1608 and Sir Thomas Roe established the first formal embassy to the Mogul court in 1615. As a result of these contacts, Samuel Purchas had a variety of sources to draw on by the time his multivolume work was published in 1625.39

English ships and merchants were lured beyond the southern tip of Africa by the same promise of rich rewards in valuable commodities that dared them to chart the Russian interior and broach the Mediterranean market during the late sixteenth century. And just as they had difficulty avoiding the subject of human bondage in these regions, English observers took notice of the nature and character of slavery further east. Considering their precarious and decidedly dependent status in the region, the accounts authored by early English merchants in the Indian Ocean and Asia are particularly interesting because these Englishmen were not in the market for slaves, as their countrymen would later be in Africa.40 Equally important, unlike the accounts written about slavery in the Mediterranean world, the English who plied their trade in the Indian and Pacific Oceans were not necessarily worried that they might themselves be enslaved.41 For this reason, the handful of English reports about the presence and use of slaves in this arena are generally characterized by a much more matter-of-fact tone than those that emanated from the Mediterranean, where the slaves that interested English commentators the most would prove to be their fellow countrymen (particularly during the seventeenth century). Still, English observers did not shy away from drawing often negative conclusions about the indigenous slave systems of south and southeast Asia.

In Java, for example, the English factor Edmund Scot commented on the tenuous existence of slaves whose masters “may execute them for any small fault.” Javan elites often kept large numbers of Chinese slaves, so many that “[t]he Gentlemen of this Land are brought to bee poore, by the number of their Slaves that they keepe, which eate faster then their Pepper or Rice groweth.” Scot also made at least passing reference to concubinage of a sort found in the Mediterranean world when he observed that for every wife that a free Javan married “he must keepe ten women-slaves.” Scot sympathized with the plight of slaves in Java, who suffered under masters some Englishmen characterized in the harshest terms. Javans were, in Scot’s opinion, “idle” and “much given to stealing, from the highest to the lowest, and surely in times past, they have beene Man-eaters, before the Traffique was had with them by the Chynasses.” An earlier account reprinted by Purchas, however, presented a less flattering view of the Chinese. Among their vices was the tendency of those who “finding their family too numerous sell their Sonnes and Daughters as Beasts, for two or three pieces of Gold (although no dearth provoke them) to everlasting separation and bondage [so that] the Kingdome is full of Slaves, not captived in warre, but of their owne free-borne.”42

Although Scot characterized the Chinese as the most common slaves in Java, other English accounts made it clear that just as all the nations of Asia enslaved, all the people of the region were subject to enslavement. As with accounts about slavery in the Mediterranean world, just how (precisely) individuals became slaves did not elicit extended consideration. Purchas did include an account of the voyage of François Pyrard de Laval to the East Indies in 1601 who noted blithely, “Slaves are such as make themselves so, or such as they bring from other places.” More commonly, European observers noted only who was enslaved rather than how he or she had been enslaved. Peter William Floris recorded in his journal that one ruler in Siam, “a mightie Kingdome and ancient,” had “amongst other Slaves, two hundred and eightie Japanders.” In Patania, also on the Malay Peninsula, they were “richest in Slaves of Javonians.” David Middleton, an energetic captain in the service of the East India Company, described the slaves of “Pulaway” (Pula Ai), an island off the coast of Sumatra, simply and unhelpfully as “Blackes.”43 Slaves in Asia were not delineated by any one national, racial, religious, or cultural characteristic. They were, on the whole, merely the unfortunate victims of random predation or unlucky to have been on the losing side in a larger conflict. Sometimes the only thing that can be said with certainty is that they were generally outsiders.

Slavery was also part of the fabric of life in Japan, at least according to John Saris, who sailed there in the service of the EIC in 1613. Saris was among the small group of Englishmen who established a trading outpost on the small island of Hirado, located in the southwestern part of Japan. Although he departed after only a short stay, he did relate that slaves in Japan were valued primarily for the prestige they imparted on their owners, including the English. Even before the English had formally set up their factory, William Adams (whose own misfortune had led to his abandonment in Japan a decade earlier) bragged in a letter written in 1611 that he had managed to do so well for himself that “th’Emperor hath geven me a living, as in England a lordshipp, w’th 80 or 90 husbandmen that be my slaves or servauntes.” Adams seems to have been deeply interested in ingratiating himself with local elites and his newly arrived countrymen, but Saris also commented somewhat favorably on the honorific value that slaves could bestow on their masters when he commented that, “[a]ccording to the custome of the countrey, I had a slave appointed to runne with a Pike before me” when he moved about the countryside. Whether Adams’s husbandmen or Saris’s pikeman were indeed slaves seems less important than the fact that the two Englishmen chose to characterize them as such for their intended audience of English readers.44

As much as Adams and Saris were impressed by their slave retinues, they and others were much more intrigued by female slaves. Saris related the tale of three men who were executed for stealing a female slave. Indeed, most of Saris’s references to human bondage in Japan were to female entertainers and the men who shopped them to the nobility. The existence of sexual slavery in Japan was difficult for English observers to ignore, but Saris was equally interested in the men who facilitated the industry. “These women are the slaves of one man,” Saris recounted, “who putteth a price what every man shall pay that hath to doe with any of them.” These male purchasers, however, were complicated figures. “When any of these Panders die (though in their life time they were received into Company of the best, yet nowe as unworthy to rest amongst the worst),” Saris noted with morbid curiosity, “they are bridled with a bridle made of straw as you would bridle an Horse, and in the cloathes they died in, are dragged through the streetes into the fields, and there cast upon a dunghill, for dogges and fowles to devoure.”45 The men who dealt in female slaves were richly valued for the commodities they provided during their lives, but few were willing to accord them (or their memory) with any sense of dignity or honor once they ceased being useful.

Whatever they may have thought about these subjects at home, English merchants willingly adapted themselves to their local surroundings as part of a larger survival strategy that necessitated flexibility and open-mindedness.46 Whether survival depended on slavery is open to debate, but English merchants nonetheless embraced the practice. Englishmen may have acknowledged that slavery was inconsistent with the way things operated at home, but they sometimes accepted that slavery was normative and benign when they encountered it in other places and did not automatically conclude that it was a prime indicator of social degeneracy. Not surprisingly, then, Englishmen abroad were as likely to purchase slaves for their own use as they were to criticize the practice among their hosts. During the tenth EIC voyage under the command of Thomas Best, the commander freely purchased slaves on at least two occasions as his two ships sailed off the northern tip of Sumatra in July 1613, the second time numbering “about 25 or thereabout Indeans, for to suplie the want of our men deceased.” The first generation of English merchants in Japan eagerly and without shame welcomed the opportunity to purchase concubines. Richard Cocks, in a letter to his colleague Richard Wickham, openly bragged that he “bought a wench yisterday” who “must serve 5 yeares” and then either repay back the purchase price or exchange “som frendes for her, or else remaine a p’petuall captive.” Cocks continued with even more shocking details, noting that the girl “is but 12 yeares ould, over small yet for trade, but yow would littell thynke that I have another forthcominge that is mor lapedeable,” or ready for sexual activity. Although not all Englishmen were as crass about the subject, many of them recognized the advantages of buying and owning slaves in the region.47

* * *

Slavery was a global phenomenon, so only its absence in Africa would have been surprising. Few English merchants or mariners actually visited Africa before the last half of the sixteenth century, by which time the practice of slavery had been somewhat altered by the predatory activities of other European merchants and slave traders. Even so, an expansive body of literature was available for public consumption, which allowed literate Englishmen to learn about African practices. Among the most popular works were the medieval travelogues that had originally circulated in manuscript but were subsequently translated into the vernacular during the early modern era.48 London printers issued an edition of The Most Noble and Famous Travels of Marcus Paulus in 1579, and the most popular work of the day, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, appeared in English, in one version or another, at least six times between 1496 and 1583.49 Curious readers could also discover information about Africa and Africans in the recently translated geographical works of classical authors, including Ptolemy (1532, 1535, 1540), Pliny the Elder (1566, 1585, 1587, 1601), Herodotus (1584), and Pomponius Mela (1585, 1590). Moreover, influential Greek and Latin texts such as Ptolemy’s Geographia and Strabo’s De situ orbis continued to be at the heart of university curricula.50 Other Europeans, especially the Portuguese, also wrote important texts that shed light on both West and East Africa. English printers published translations of the diplomatic exchanges between agents of Portugal and Ethiopia during the reign of Henry VIII.51 Several other English translations of Portuguese activities in Africa and the East Indies appeared during the sixteenth century, including Duarte Lopes’s A reporte of the kingdome of Congo (1587). Beyond this large body of material, promoters like Richard Hakluyt and Samuel Purchas compiled, translated, and published numerous narrative accounts that provided detailed information about the people, societies, geography, climate, and commodities of Africa. Large parts of Africa would remain a mystery to even the most intrepid Europeans for a long time to come, but adventurous readers had plenty of information at their disposal during the sixteenth century.

Collectively, these authors and translators presented Africa as an exotic and mysterious place that was alternately alluring for the spiritual and material rewards it promised and terrifying for what awaited those few individuals unfortunate enough to actually go there. Most important, among the many possible lines of inquiry, classical and medieval authors did not dwell on the subject of slavery. Africa’s defining characteristic was arguably its climate, which authors invariably described as unbearably hot. William Prat’s 1554 translation of Johann Boemus’s Omnium gentium mores described “the lande of Ethiopie” as the “neighbour to the sonne, as before al other to feale the heate.” Boemus also translated “Athiopes” in a way that emphasized the point, claiming that the word derived from the Greek “Atho which signifieth burne and Oph which signifieth take hede, and that because of the approchynge nyghe to the soone [the Sun]. The countreye is continually hote.” As a result, the inhabitants of Africa possessed characteristic features, most noticeably their skin color. As George Abbot observed in 1600, “All the people in general to the South, l[i]ving within the Zona torrida, are not onely blackish like the Moores, but are exceedingly blacke. And therefore in olde time, by an excellency, some of them were called Nigrita; so that to this day they are named Negros, and then whome, no men are blacker.”52

Figure 1. Detail from the lower-left quadrant of the title page of Historia mundi: or Mercator’s Atlas. Containing his cosmographical description of the fabricke and figure of the world (London, 1635). By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Africa, numerous authorities reported, was also a land of monstrous races of men. The authoritative text on this subject was Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis, translated into English by Philemon Holland in 1601 (although an excerpted version had previously appeared in 1566). In the account of the “Æthyopians,” Pliny described the existence of peoples whose differences could be relatively subtle, like the “Troglodites” who lived in caves and fed “upon the flesh of serpents” and the “Garamants” who were intriguing because they “live[d] out of wedlocke, and converse with their women in common.” Some differences were quite stark: “The Blemmyi, by report, have no heads, but mouth and eies both in their breast. The Satyres besides their shape onely, have no properties nor fashions of men” and the “Himantopodes bee some of them limberlegged and tender, who naturally goe creeping by the ground.” Sir John Mandeville made even more of these characters, including a passing reference to a “monstrously shaped beast” who lived in Egypt that “had the shape of a man from the navel upward, and from there downward the form of a goat, with two horns standing up on its head.” South of Ethiopia, he added, was “a vast country, but it is uninhabitable because of the terrible heat of the sun.” Nonetheless, there you could find “some who have only one foot” that “is so big that it will cover and shade all the body from the sun.” Those who traveled farther, to India and Southeast Asia, might even come across “people whose ears are so big that they hang down to their knees,” “people who walk on their hands and their feet like four-footed beasts,” hermaphrodites, and people who “live just on the smell of a kind of apple.”53

If classical and medieval sources compelled the English to imagine a world to their south inhabited by strange and monstrous beings, Christianity played no less an important role in how Europeans wrote and thought about Africa (or any other place, for that matter). First, even if English and other European authors were disinclined to explain the physical appearance of African people with reference to the so-called Curse of Ham, a number of writers did associate African peoples with the biblical passage. Boemus’s Omnium gentium mores, which appeared in two separate English translations (in 1554 and 1555), is once again representative. Recounting the origin of the division of the world, Boemus reported that Cham, “by the reason of his naughty demeanour towarde his father” was “constrayned to departe with his wyfe and hys chyldren” and subsequently “lefte no trade or religion to his posteritie, because he none had learned of his father.” If Cham and his descendants were cursed with darkness, it was clearly a spiritual rather than a physical matter. Thus, over time “some fel into errours whereout they could never unsnarle themselves” and eventually “some lived so wildely … that it ware harde to discerne a difference betwixte them and the beastes of the felde.” John Pory noted that most of the inhabitants of Africa, excluding “some Arabians,” were “thought to be descended from Cham the cursed son of Noah,” but he did not elaborate on the subject any further.54 Although there were exceptions, few domestic English authors were willing to embrace the idea that the skin color of Africans was wholly attributable to a curse handed down by Noah.

Second, and more important, Christian Europeans dreamed of Africa because of the potential presence of Prester John. An anonymous fourteenth-century Spanish Franciscan traveler, whose observations survive today as the Book of the Knowledge of All the Kingdoms, Lands, and Lordships that Are in the World, described Prester John as the Patriarch of Nubia and Abyssinia, which were “very great lands” with “many cities of Christians.”55 The origins of the Prester John myth date to the twelfth century when news reached Pope Eugenius III that a powerful Christian king in the East stood ready to assist European Christians in their ongoing struggles against Islam. It was unclear where this fabled king may have been located, but his rumored presence served as a rationale for voyages of discovery and other official missions to both Asia and Africa during subsequent centuries. Three hundred years after he first appeared, Prester John continued to be an enticing, if illusive, figure whose greatest legacy may have been the Portuguese effort to establish direct contact with Ethiopia.56 Other Europeans, however, were also intrigued by stories about “the kynge of Ethiope whiche we call pretian or prest John whom they cal Gian,” a man who, in Johann Boemus’s words, was “of so great a personage and blud, that under him he hath threscoore and two other kynges.”57

There were always serious doubts about the veracity of these legends, but even Henry IV of England had written to Prester John in 1400 asking him to lend his support to the reconquest of the Holy Land. Still, the small chance that there might be a powerful Christian kingdom to the south was too tantalizing to dismiss out of hand. Abraham Hartwell was moved to declare in his 1597 translation of Duarte Lopes’s A Report of the Kingdom of Congo, if “Papists and Protestants” and “all Sectaries and Presbyter-Johns men would joyne all together” they would be able “to convert the Turkes, the Jewes, the Heathens, the Pagans, and the Infidels that know not God but live still in darkenesse.”58 Yet, Prester John increasingly appeared in English sources more as a caricature designed to amuse readers than as the leader of a kingdom that might actually exist. In 1590, Edward Webbe claimed to have visited Prester John’s court, where he encountered “a king of great power” and “a very bountifull Court.” At the same time, he also claimed that at the court of Prester John there was “a wilde man” who was “allowed every day a quarter of mans flesh” whenever someone was executed for “some notorious offence.” In addition, he declared that there was “a beast in the court of Prester John, called Arians, having four heades” that were “in shape like a wilde Cat.”59 Like Webbe, George Abbot linked Prester John with the fantastic rather than the sacred. Drawing from Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturalis, he noted at the end of his consideration of Prester John’s kingdom that Africa “bringeth forth store of all sortes of wilde beastes,” including “newe and strange shapes of beastes.” These new creatures, according to Abbot, were a result of “the country being hot and full of wildernesses which have in them little water.” Thus, “the beastes of all sortes are inforced to meete at those fewe watering places…; where, oftentimes contrary kindes have conjunction the one with the other: so that there ariseth newe kindes or species, which taketh part of both.”60

Before they went to Africa, Englishmen learned about the place and its peoples as best they could from an array of manuscript and printed sources. After the 1590s, it was increasingly likely that English readers could read accounts authored by Portuguese, Dutch, and even English merchants and sailors who had spent considerable time in the places about which they wrote. The Portuguese had been actively engaged in diplomacy, commercial exchange, and religious conversion with West Africans for more than a century before English readers and mariners began to demonstrate any serious interest in the region. Portuguese texts, even when they did not find contemporary English translators, were typically the only sources interested English readers could find before the 1550s and continued to be among the most detailed accounts available to them through the end of the century. Even when the works of authors such as Cadamosto and Barros were not mentioned directly, evidence suggests that English authors and editors like Richard Eden, Humphrey Gilbert, Richard Willes, John Pory, Hakluyt, Purchas, and others relied heavily on Portuguese sources.61 When Portuguese accounts were read alongside some of the recently translated and very rich Dutch sources, especially Jan Huygen van Linschoten’s Itinerario, which was translated and published in England in 1598 at the recommendation of Richard Hakluyt, English readers were able to learn a great deal about West African polities, the nature of their religious practices, and the wealth of commodities that circulated along the African littoral.62

Dog-headed men and the descendants of the Magi would continue to fascinate Englishmen for years to come, but increasingly the English were reading about an Africa that was of interest because it was “full of Gold and Silver, and other Commodities.” As Englishmen traveled to Africa, George Abbot reported, they “found trafique into the parts of the country: where their greatest commoditie is golde, and Elephants teeth: of both which there is very good store.”63 These items were made available for trade by the numerous sophisticated polities that could be found along the West African littoral. These linguistically and culturally diverse kingdoms ranged in size from a few hundred people to tens, if not hundreds, of thousands. Although they could be difficult for Europeans to describe with precision, African societies were dynamic and often as technologically and materially sophisticated as European societies. Active, long-distance trade networks blanketed the continent. Local rulers regulated trade and moderated the commercial activities of merchants. Cloth and iron manufacturing were characteristic features of local and regional economies. There was also slavery. Although it was an institution that existed to serve different needs and was justified by different criteria than the plantation-labor institution that would subsequently come to dominate the Atlantic slave system, slavery was as pervasive in African societies as it appeared to be in other parts of the world. Of course, there was an important difference. Although enslaved Africans were exported out of Africa by European traders in small numbers to start with, and constituted a small fraction of the value of all African exports before the seventeenth century, all Europeans took advantage of the availability of African peoples as commodities both at home and, especially, in their Atlantic world colonies.64

Slavery was nothing new to the inhabitants of Africa; it was not, as one historian notes, “an ‘impact’ brought in from outside.” Rather, “it grew out of and was rationalized by the African societies who participated in it.”65 Not surprisingly, disagreements persist about the relative importance of the institution before the arrival of European ships in the fifteenth century and a number of scholars suggest that slavery was a relatively insignificant social and economic institution until the Portuguese, French, English, and Dutch began exploiting African peoples. Nonetheless, slavery clearly existed in various sub-Saharan African societies as a tribute mechanism, a domestic institution, and, in rare cases, an industrial system. Thus, by the time the English began arriving in small numbers during the late sixteenth century, nothing would have surprised them more than the absence of slavery. Europeans were familiar with the commodity value of African peoples from their dealings with North Africans who had facilitated the trade in sub-Saharan Africans into the Mediterranean and southern European worlds for several centuries before Europeans began sailing southward.66 The English saw slavery wherever they looked. Why should Africa be any different?

English merchants entered the African trade slowly.67 During the 1530s and 1540s, as many as six English expeditions touched base on the eastern Atlantic seaboard of Africa. The most famous of these were the three expeditions to Brazil between 1530 and 1532 launched by the wealthy Plymouth merchant, William Hawkins, during which time the English captain “touched at the river of Sestos upon the coast of Guinea, where hee traffiqued with the negros.”68 A few decades later, however, English ships began to journey to Africa for the express purpose of regularizing a direct trade. During the 1550s and 1560s, when Englishmen and Africans encountered each other for the first time in a sustained fashion, perhaps a dozen expeditions, involving as many as 1,500 English mariners, sailed the waters between the southern coast of England and the western shores of Africa. But as vital as the English effort seemed to be during this early stage, the African trade presented numerous complications for English merchants, not least of which were the devastating mortality rates. As Richard Eden recounted about the 1558 expedition of Thomas Wyndham, “of the sevenscore men” who set out from Plymouth, there returned “scarcely forty, and of them many died.”69 Africa was a destination from which shocking numbers of English mariners failed to return.

The transatlantic slave trade was, in many ways, still in its infancy during the sixteenth century, but thousands of captive Africans were already being loaded onto European ships and transported across the sea to Spanish America and Brazil every year, especially after 1560.70 In this vein, an expedition under the command of John Lok reportedly returned to England with “certayne blacke slaves” in 1555. Although a small number of sub-Saharan Africans had been in the British Isles before this date, their arrival was remarkable. According to Eden, “sum were taule and stronge men, and could well agree with owr meates and drynkes.” At the same time, the “coulde and moyst ayer dooth sumwhat offende them.” The difficulties and sufferings of the indigenous inhabitants of equatorial Africa transplanted to England’s colder clime were not surprising: “[D]oubtlesse men that are borne in hotte regions may better abyde heate” than cold. But what about their apparent status as “slaves”? Certainly, these Africans were not slaves in the modern sense of the term. The English viewed these five men more as cultural mediators than as bondmen. William Towerson, a London merchant and commander of three well-documented expeditions to Africa (1555, 1556, and 1558) reported to a group of Africans during his first voyage that “they were in England well used, and were there kept till they could speake the language, and then they should be brought againe to be a helpe to Englishmen in this Countrey.”71 When three of the original five Africans who had been taken to England returned to Africa with Towerson on his second voyage, then, the English saw them as mechanisms that would make it easier to acquire gold, pepper, and ivory. To this end, the “slaves” proved their worth immediately. At one point, Towerson reported meeting some Africans who “would not come to us, but at the last by the perswasion of our owne Negros, one boat came to us, and with him we sent George our Negro ashore, and after he had talked with them, they came aboord our boates without feare.”72

The characterization of the five Africans on board Lok’s ships as “slaves” may have been a label of convenience rather than a true indication of their condition and, certainly, West Africans in general had little to fear from the English during their early voyages. Even so, some Englishmen clearly embraced the slave trade from an early date and accepted that it was a necessary component of successful African enterprises. In 1555, a group of English merchants petitioned Queen Mary in order to obtain free trade privileges in Guinea. They claimed that earlier English expeditions to Africa had uncovered several local rulers who were happy to trade with English ships. In addition, the “said inhabitauntes of that country offred us and our said factors ground to build uppon, if they wold make anie fortresses in their country, and further offred them assistaunce of certen slaves for those workes without anie charge.”73 These English merchants recognized the advantages of a captive labor force as well as the importance of the willing assistance of African merchants and leaders.

The rapid English embrace of African slavery, however, was demonstrated most clearly during the 1560s when four English expeditions (three of which were led by John Hawkins) sailed to the African coast, filled their holds with Africans, and sold their human cargoes in Spain’s American colonies. Hawkins’s first expedition, which departed England in 1562, consisted of three ships and “not above 100. men for feare of sicknesse and other inconveniences.” The small fleet sailed to Sierra Leone and, “partly by sworde, and partly by other means,” acquired “300. Negros at the least, besides other merchandises which that country yeeldeth.” As quickly as possible, the ships sailed on to the Caribbean where they unloaded their cargo. By September 1563, they were back in England. Hawkins set sail again the following year with a slightly larger and much more powerful fleet of four ships and more than 150 men. This expedition was broadly similar to the first and succeeded in capturing or trading for 400 Africans, who they subsequently transported across the Atlantic and sold into slavery. John Lovell attempted to sail in his former commander’s wake two years later when he left Plymouth with three ships, but he lacked Hawkins’s skill, or good fortune, and only managed to acquire and sell a few slaves. Lovell’s small fleet was largely dispirited and none-the-wealthier when it returned to England in 1567.74

The most notorious English expedition to Africa during the sixteenth century was the final slave-trading expedition launched and led by John Hawkins in 1567. This massive expedition was a grand scheme and represented a serious commitment to the slave trade on the part of Hawkins, numerous investors, and Queen Elizabeth herself. By contemporary standards, the fleet was impressive, consisting of six ships, including two royal warships. In a letter from Plymouth drafted shortly before his departure, Hawkins confidently assured Elizabeth that he would return from the West Indies laden with “gold, pearls and emeralds, whereof I doubt not but to bring home great abundance to the contentation of your highness and to the relief of the number of worthy servitures ready now for this pretended voyage.” Departing Plymouth in October, the fleet reached Cape Verde in mid-November and proceeded to try to “obtaine some Negros,” but they “got but fewe, and those with great hurt and damage to our men.” Hawkins continued down the coast to Sierra Leone and prepared to give up on his grand scheme, having procured fewer than 150 slaves, when “there came to us a Negro, sent from a king, oppressed by other Kings his neighbours, desiring our aide, with promise that as many Negros as by these warres might be obtained, aswell of his part as of ours, should be at our pleasure.”75 After a disappointing start, then, things appeared to be looking more positive for the English slave traders.

Having learned the painful lesson that he could not simply dispatch his men to the coast to waylay random Africans without great difficulty, Hawkins prepared to work in consort with an African ally. Together, they attacked and set fire to a village housing approximately 8,000 people. As the inhabitants fled for their lives, Hawkins and his men managed to capture “250 persons, men, women, & children, and by our friend the king of our side, there were taken 600 prisoners, whereof we hope to have had our choise.” Hawkins was disappointed, however, when “the Negro (in which nation is seldome or never found truth) … remooved his campe and prisoners, so that we were faine to content us with those few which we had gotten our selves.” Thus, with perhaps 500 Africans on board, the English fleet set sail for the West Indies in early February. After a difficult journey, they arrived in the West Indies and “coasted from place to place, making our traffike with the Spaniards as we might, somewhat hardly, because the king had straightly commanded all his Governors in those parts, by no meanes to suffer any trade to be made with us.” By the end of July, the English ships were ready to depart, but in August, off the coast of Cuba, they were caught in “an extreme storme which continued the space of foure dayes.” Initially, they sought safe harbor in Florida to repair their ships, but another storm forced them westward and compelled Hawkins to seek relief at San Juan de Ulloa on the coast of Mexico near Veracruz. There, however, they soon found themselves trapped by the newly arrived Spanish flota. The two sides initially maintained an uneasy peace. Unfortunately for the English, the Spanish viceroy, Don Martín Enríquez, had no intention of allowing the privateers to go unchallenged. Within days, the Spanish attacked and devastated the English force. Two ships, the Judith and the Minion, managed to get past the Spanish fleet and safely out to sea, but three other ships were destroyed and a majority of the men were abandoned to their fate in New Spain. Of the roughly 400 men who set sail with Hawkins in 1567, only about 100 returned to England in 1568.76

Figure 2. Sketch of the arms and crest (a bound African slave) granted to Sir John Hawkins in 1568. “Miscellaneous Grants 1,” fol. 148r. By permission of the College of Arms, London.

With the notable exception of these four slave-trading expeditions during the 1560s, few Englishmen went to Africa to participate in the transatlantic slave trade before the mid-seventeenth century. Hawkins’s voyage was such an unmitigated financial and diplomatic disaster that there was little in it to suggest that it was worth imitating. Hawkins was even compelled to draft a very public defense of his enterprise upon his return in which the duplicity of the Spanish and bad weather featured most prominently among the list of explanations for the voyage’s failure.77 In subsequent decades, therefore, only a small number of English merchants attempted to profit from the transatlantic slave trade. In 1587, two English ships were granted safe passage by the Portuguese government to trade textiles into the Azores where they were to acquire wine that would be used for the purchase of slaves in Guinea or Angola, which would then be exchanged for sugar in Brazil. Illicit trading in black slaves was also sporadic during the early decades of the seventeenth century, though English merchants often had other more pressing interests in Africa.78 When the Company of Adventurers of London trading to Gynney and Bynney was formed in 1618, the corporation was primarily interested in the gold trade. Although the company established a fort on the Gambia River and sponsored three voyages between 1618 and 1621, the business venture was largely unsuccessful. Eventually, the company was reorganized under the leadership of the London merchant Nicholas Crispe and granted a new monopoly as the Company of Merchants Trading to Guinea and it proceeded to establish additional outposts in Sierra Leone and along the Gold Coast. Even then, gold and lumber were more likely than slaves to be listed as the desired commodities.79 Hawkins’s disaster was a hard-learned lesson and the English government and its merchants were not quick to forget it—the slave trade was dangerous.