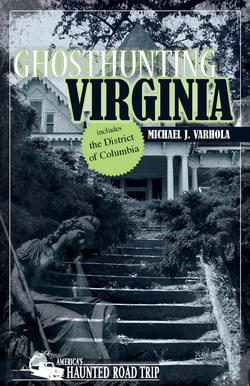

Читать книгу Ghosthunting Virginia - Michael J. Varhola - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 4

Manassas National Battlefield Park

PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY

A friend of mine does Civil War reenactments, and he was at Manassas, Va., while a tour guide was enlightening a group of little kids. “He was telling them about how the 5th New York Zouaves had been wiped out right near where they were standing at Second Manassas,” my friend said. “He asked them if they knew what a Zouave uniform looked like,” my friend went on, “and one little girl said they wore baggy red pants and blue jackets and funny red hats. When the guide asked how she knew that, she pointed to a cannon at the top of a nearby hill and said, ‘One of them was standing up there.’ “We looked, but nobody was there.”

—Jim Goldsworthy, Cumberland Times-News

BACK IN THE 1990s when I was running Living History magazine, I heard any number of stories from Civil War reenactors about ghosts on the Manassas Battlefield, and, if memory serves, many of them described spectral formations glimpsed in the misty darkness of predawn. I also talked or corresponded with a couple of psychic researchers in those days, and they confirmed their impressions of lingering spiritual energies at the site of the first major clash between Union and Confederate forces.

It certainly makes sense that if any battlefield were haunted it would be Manassas. After all, it was the site of two bloody confrontations within the space of a year—the second one far larger than the first—and thus has a double layer of psychic trauma associated with it.

Like most Civil War battles, each of the ones fought at this location has two names, one bestowed by the North and one by the South, a convention that can cause some confusion for novice historians or those with only a casual interest in the subject. Union commanders usually named battles for the nearest rivers, streams, creeks, or “runs,” while Confederate leaders generally named them for towns or railroad junctions. It is thus that the two battles fought at this site are variously known as the First Battle of Manassas and the Second Battle of Manassas for nearby Manassas Junction (a practice often adopted to this day by those sympathetic to the Rebel cause), and as First Battle of Bull Run and the Second Battle of Bull Run for a neighboring stream (the official names given them by the U.S. government). We will use the former term here not because of sympathies one way or the other but because it corresponds with the name of the park associated with it.

The First Battle of Manassas was fought July 21, 1861, by formations of enthusiastic, brightly uniformed volunteers who on both sides were confident that their opponents would turn and run and that they would that day witness the end of the war. Despite a favorable outlook for the 35,000-strong Union forces early in the day, some 32,500 Confederate troops ultimately drove their opponents from the field in rout. Credit for much of this victory has been accorded to Brigadier General Thomas Jackson, who that day earned the nom de guerre “Stonewall.” Both fledgling armies were left disorganized and bloodied, with Northern casualties of 460 killed, 1,124 wounded, and 1,312 missing or captured, and Southern casualties of 387 killed, 1,582 wounded, and 13 missing. Many illusions as to the nature and duration of the war were shattered that day in the chaos, fear, and death of combat.

The Second Battle of Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, between experienced armies that were considerably larger, with some sixty-two thousand men clad in Union blue facing fifty thousand in Confederate gray over an area of more than five thousand acres. It concluded in a solid Southern victory, taking the Confederacy to its high-water mark; the prospects for the rebel cause would only become steadily bleaker over the ensuing three years. Casualties far exceeded those of the earlier battle, and for the Union were about ten thousand killed and wounded and for the Confederacy about thirteen hundred killed and seven thousand wounded.

It is little wonder then that so many ghost stories should be associated with the place, especially in the decades since 1940, when the park was officially established by the National Park Service. These have been so widespread as to periodically catch the attention of various local news organizations.

“Visitors … have reported seeing house lights where there is not a house, smelled the scent of black powder and once ‘the smell of burning flesh,’” reported the Washington Post in a 1989 article, for example. “Park employees have also testified to sudden drops in temperature on muggy days and baffling noises in the battlefield Stone House.” Any number of accounts of personal experiences, sightings, or investigations can be found in numerous articles, books, and online postings.

Many of the most prolific and convincing ghost stories involve the 5th New York Volunteer Infantry regiment, dubbed “Duryée’s Zouaves,” a Union unit that in August 1862, according to historian Bruce Catton, “lost 117 men killed and 170 wounded, out of 490 present—the highest percentage of loss, in killed, suffered by any Federal regiment in one battle during the entire war.” In the years especially since the park was established, many people have reported seeing one or more apparitions clad in the distinctive uniforms of this ill-fated formation at various locations in the park, especially near the monument dedicated to the fallen soldiers.

“There, at dusk, images of members of the 5th New York Zouaves—who were cut to pieces during the Second Battle of Manassas—have been seen beckoning by the woods at the western end of the park, clad in their red pantaloons, white leggings, and nightcap hats,” wrote Diane McLellan in Washingtonian magazine in a characteristic description of what other witnesses have attested to. Variations on this story have involved a headless Zouave searching for his head, a lost companion, or possibly his way off the battlefield he marched onto so long before.

Stories concerning the Stone House, built in 1824 and run as an inn for drovers before the railroad largely supplanted them, are even more disturbing and gruesome. Used as a Confederate hospital during the Second Battle of Manassas, an account from a northern surgeon at the site states that Union troops were not just neglected but deliberately treated badly at the facility and that many of them died lingering or degrading deaths as a result.

“These inexperienced surgeons performed operations upon our men in a most horrible manner,” testified Dr. J.M. Homiston of Brooklyn. “The young surgeons, who seemed to delight in hacking butchering [our men], were not, it would seem, permittde to perform any operations upon the rebel wounded.”

With trauma like that associated with the place, it should not be surprising that so many reports of paranormal phenomena are associated with the Stone House, and written accounts from at least the early twentieth century claim that it is cursed in addition to anything else. It would seem that some sort of unquiet spirits occupy the place, and incidents people have reported include hearing footsteps in the unoccupied rooms above them and having glasses knocked off their faces.

I have only visited Manassas National Battlefield Park once, and that was relatively recently, in November 2006, with my daughter Hayley, grandma Val, and grandpa Jim. I will not say it is unfortunate that it has been unseasonably bright and sunny during my visits to a great many of the places described in this book. But, suffice it to say, such seemingly ideal conditions have certainly allowed me to assess the odds of various sites being haunted without atmospheric distractions like wind, rain, cold, darkness, or any number of other factors that could enhance the appearance that they are. And so, for a day near the end of the year, it was strikingly warm and clear during our trip to the battlefield.

After touring the exhibits in the Henry Hill Visitor Center and watching an orientation film titled “Manassas: End of Innocence,” we decided to walk the one-mile loop trail that meanders across the rolling terrain corresponding to where the first battle was fought. During the walk we passed a number of interesting features, including a recreation of the Henry House, which had been blown up during the battle—along with the old woman living in it, who became the first civilian casualty of the war. We were also able to look northwest from a point on the trail to the Stone House, the most characteristic landmark at the park, which was used as a field hospital for soldiers of both sides during each of the battles. It was all very pleasant and informative (especially the revelation that the remains of the now-vanished village of Groveton lie within the park, a whole separate source of potential investigation for ghosthunters).

It was not until we reached the end of the trail, back again near the visitor center, that I spotted something that gave me some pause. It was a statue of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson that had been erected in the 1930s and was in a style that I recognized but knew was not familiar to most Americans. In it, the mounted Jackson was almost ludicrously muscled, his chest outthrust in a heroic pose, his overall appearance suggesting Superman in a kepi and beard. He was, in fact, depicted in a style of art frequently characterized as “heroic realism” that is most commonly associated with the Nazi, Communist, and other totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. It had been erected, I suspected—considering the era when it had been dedicated—by people who, like Jackson himself, had attitudes toward civil war, race, and any number of other subjects completely alien to my own. It, more than anything else at the Manassas Battlefield, gave me a sense that the dead might yet have cause to walk the ground where they fought a century-and-a-half before, the issues for which they died still unresolved.

Statue of Stonewall Jackson