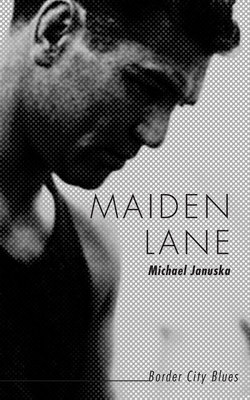

Читать книгу Maiden Lane - Michael Januska - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

— Chapter 6 —

ОглавлениеTHE MAN ON THE STREET

Campbell closed the Cadillac Café and started winding his way home through winter. Not enough ginger, he thought. Not enough ginger.

He frequented Ping Lee’s establishment on Riverside Drive because Ping kept late hours and let him order off-menu. Campbell had asked him what was fresh, and knowing what he liked, Ping skillfully assembled a succulent chicken and vegetable chow mein. The fried noodles were filling and the chicken juicy and tender, done just right, but there wasn’t enough ginger, and that’s what Campbell was most looking forward to: something to gently keep his insides warm while he measured the streets of downtown. Ping had frowned at Campbell’s ginger request at first. He didn’t believe it should be included in this recipe that he took great pride in preparing. But he liked Campbell; he always told him he was “okay.”

Campbell occasionally went to Ping just for information, but knew better than to call it that. Informants in the Border Cities, particularly those who worked or resided along the river, had a tendency to disappear. He told Ping that he sought his opinion, his sage advice.

The wisdom of the Orient.

Ping smiled the first time he heard Campbell use that phrase.

What’s so funny?

Campbell eventually stopped using it.

He was looking for Ping’s thoughts on Judge Gundy’s decision this morning. He had a copy of the Border Cities Star opened in front of him on the counter. “Two Chinese Get Big Fines.” It was an opium trafficking case. The fines followed a messy RCMP bust at a grocer’s on the other side of the Avenue. Ping was his usual philosophical self.

Dou yan.

What?

One of his daughters happened to be standing nearby, stacking hot, clean plates. She bridged the divide for them.

He say, you cross-eyed.

Really? What else does he say?

Not much. Not tonight.

Campbell stopped telling anyone at the department about his surveys of the city streets in his off hours. He had thought they would have appreciated it, respected his desire to know the territory as well as any constable walking a beat. Chief Thompson told him he was wasting his time and the other cops said, in not so many words, that he was cutting their grass. They also thought he was checking up on them, maybe being used by Thompson to keep tabs on them. Things didn’t used to be this tangled up, thought Campbell. Regardless, he quietly kept to his routine.

Every intersection was an open invitation to the bitter wind. Campbell pulled his overcoat collar up against the elements. It did little good. He hated doing it, but he decided to shorten tonight’s planned circuit by taking Pelissier Street up to Wyandotte, and then loop back north toward his apartment once he crossed the Avenue.

The wind whistled around the slack in the telephone wires and howled through the gaps between buildings. Any warmth Campbell might have been carrying with him was quickly dissipating; he could barely feel his nose, and his cheeks smarted like they’d had a good slapping.

A strange amber flash in the big windows along the side of Meretsky & Gitlin’s furniture store caught his eye. It was a reflection. He glanced up at a dying streetlight and that was when he noticed the snow swirling overhead. Pulling his collar up further, his bowler down lower, and plunging his gloved hands even deeper into his pockets, he continued on his chosen path.

No traffic on London Street. No streetcar wheels grinding to a stop on frozen tracks. No sputtering motors. No surprises. He shifted his eyes over toward the darkened Capitol Theatre as he crossed. It would have recently emptied. It was the last night for Heroes of the Street; he had meant to catch that one.

Probably just as well.

He continued his brisk pace. At Park Street, the businesses gave way to simple clapboard houses. They didn’t hug the sidewalk and didn’t throw much light. The snow was landing now and he was picking up the smell of wood and coal burning. He had resisted long enough; he paused at the top of Maiden Lane to light a cigar. He dug deep through his layers to find it, procured under the counter from Ping, and his Ronson. The spark, a flash, and the aroma. He was feeling better already. But only for a moment.

The crash cleaved through the night. Campbell instinctively ducked, but his curiosity made him turn just in time to see a shadow hit the pavement along with broken glass and what appeared to be windowpane. He looked up and saw a curtain billowing out of a yawning gable in the third storey of the sole dwelling on Maiden Lane. He ran over. The body was splayed out in the dusting of freshly fallen snow. Blood was pooling around the head and glass fragments glittered in the streetlight. Campbell unhitched the flashlight from his belt, picked the victim’s pockets, and found a wallet. He opened it, found some identification and then his mind kicked into gear.

Kaufman: Male, foreigner; year of birth 1867. Right cheekbone crushed from impact; cuts on his face attributable to glass; broken right arm raised over his head; cuts on his hand also from glass; left forearm tucked under his midsection; body twisted slightly — both feet pointing to the right.

A constable came running from the Avenue, not thirty yards away. He was surprised to see Campbell already on the scene. “I rang the box, sir.” Maybe his way of saying he would have been there sooner.

Campbell noticed a neon sign hanging in the ground floor window of the house. No other light came from the window. The sign looked like an eye. Below it, painted on the glass were the words Madame Zahra’s Astral Attic. A small parade of concerned citizens dressed in bathrobes, overcoats, galoshes, and other people’s hats came staggering, bleary-eyed, out of their homes along Pelissier and the Avenue, converging on the house on Maiden Lane. Campbell pulled the cigar out of his mouth. “Send up whoever from the department gets here first,” he said, before pointing his cigar at the gawkers, “and keep these people back.”

There were no fresh footprints on the front steps. The entrance was unlocked. Campbell entered. On the other side of the tiny vestibule was a longish, narrow hall. First to the right was a locked door, and just ahead on the left was a staircase, with light coming from above. He leaned against the handrail and looked up. A fixture was dangling above the second-floor landing. Campbell took to the stairs, two at a time, until they delivered him through the floor into a tiny attic apartment.

He felt as though he just passed into another world, and in some ways he had. It resembled a gypsy tearoom from a Hollywood movie. Stepping up, he first noticed the stars painted on the ceiling; then the richly patterned wallpaper; iconography and idols; fringes, tassels, incense, and candles. He was so distracted by the décor it took him a moment to notice the three people sitting around the table to his left and a fourth chair tipped onto the floor. A woman whose costume and demeanour suggested she was none other than Madame Zahra appeared calm. The other two, older, about the victim’s age, appeared agitated. The trio made eye contact with him but did not move or speak. They appeared frozen in the moment. He left them in that state while he quickly examined the window, a gaping hole that went almost from floor to ceiling. In addition to the winter gusts, it was also opened to a view of the neighbourhood rooflines and the bright, distant beacons of downtown Detroit.

Campbell considered the trajectory of the body. To have gone through the window and landed that far away, Kaufman either would have had to have a running start or have been thrown with a great deal of force — and the trio at the table looked to him like a card of featherweights. He looked down again and happened to catch the station’s REO as it turned from the Avenue onto the lane, coming to an abrupt stop about ten feet from the body. Campbell held his gaze until he saw a constable step out of the vehicle. He whistled and then went to the top of the stairs to greet him.

“Bickerstaff,” he shouted.

“Detective Campbell?”

The constable scrambled up the stairs and into the apartment. “What happened, sir?”

“I think the sidewalk killed him,” said Campbell.

“And what of these ones?”

“They haven’t spoken, haven’t moved. See if you can’t pull that tapestry down and hang it from the curtain rod. It’s Siberian enough in here already.”

“Sir?”

“Nothing. Has someone contacted Laforet?”

“I phoned him from the station. He was none too happy.”

“That’s because he hates the telephone. But I have a feeling he’ll like this.” Campbell pulled out his notebook and approached the table. “I’m Detective Campbell, and,” pointing behind him with his pencil said, “that’s Constable Bickerstaff. Would you be Madame Zahra?”

“Yes.”

“Is that your first or last name?”

In a tone that made her sound like she was used to random searches and interrogations, she answered, “I am Zahra Ostrovskaya.”

Campbell’s pencil hovered over his notebook. “I’ll stick with Zahra for now. A man identified as Kaufman is lying dead on the pavement outside. Was he pushed out of that window?”

Zahra said she did not see him go out the window. In what Campbell figured to be an Eastern European, possibly Russian accent, Zahra went on to explain how she did not see anything because she was in a trance.

“A what? Don’t — we’ll come back to that.” He shifted his attention to the couple. “What is your name, sir?”

“Yarmolovich. Pavel Yarmolovich. And this is my wife, Sonja. She does not speak good English.”

Campbell nudged up his bowler with the heel of his thumb. “I’ll decide whether or not she speaks English well, sir. Are you carrying any identification?”

Yarmolovich reached inside his coat, pulled out a yellowed paper, and handed it to Campbell. It unfolded into something resembling the Treaty of Versailles. Campbell scanned it. Thinking it official-looking enough, he refolded it and handed it back to Yarmolovich. He then manoeuvred toward a beaded curtain that he presumed sectioned off some sort of cooking area. He sliced through the hanging beads with his hand and parted it several inches. It was indeed a kitchen, about the size of a closet and about to collapse upon itself. He turned back to his host.

“Madame Zahra, would you wait for me in here?”

The detective widened the gap in the beaded curtain for Madame Zahra, who then slowly made her way up from the table. Campbell then sat in the chair she formerly occupied and turned his attention toward Pavel Yarmolovich.

“Did you throw Kaufman out of that window?”

Yarmolovich seemed shocked at the accusation. Or at least that’s what his performance suggested. He denied it, first in his native tongue and then in broken English, both served hot. Campbell then turned to the woman, but before he spoke a word to her, he held up his hand to Yarmolovich, just stopping himself from putting it over his mouth. The question was going to sound ridiculous, but he had to ask it. “Sonja, did you push Kaufman out of that window?”

She glanced at her husband with an expression that could only be described as incredulous and replied, “No.”

“There,” said Campbell, “now that we have gotten that out of the way, am I to conclude that Mr. Kaufman jumped out of that window?”

“Yes,” said Yarmolovich. Without checking with her husband first, the wife nodded.

“Please stay seated.”

Campbell rose from the chair and slowly walked back toward the window, along the way examining the bits of furniture, wall hangings, and the carpets on the floor. There were no signs of a struggle, nothing looked disturbed. From the window, he paced the distance back to the table. If Kaufman had jumped, it would have to have been after a running start. He sat down.

“Now, what would make Kaufman do a thing like that?”

Yarmolovich sighed and, rubbing the stubble on his chin with the back of his hand, said, “He was talking to his wife.”

“She was here?” said Campbell.

“Yes, they were arguing. Kaufman was angry, and then frightened. He got up, and then fsht,” said Yarmolovich, smacking his hands together and sliding his right palm forward, “out the window. That was when Madame Zahra came from her trance.”

“And Mrs. Kaufman, where did she go?”

“Back to the other side.”

“Other side of what?”

Yarmolovich looked at Campbell like the detective was someone who had never heard of canned peaches before. “To the spirit world.”

Campbell looked over the edge of his notebook and tipped his bowler back a little farther. “I’m sorry, but when you said Mrs. Kaufman was here, you actually meant …” With his pencil he pointed at the stars on the ceiling.

Without looking at each other, the Yarmoloviches nodded. Campbell closed his notebook and told them to sit tight; he was going to speak with Madame Zahra. But first he approached the constable, who had finished hanging the tapestry and was now positioned between the window and the entrance to the apartment.

“Bickerstaff.”

“Sir?”

“Keep an eye on things for me here,” he said, nodding back toward the Yarmoloviches. “I’m going to have a few words with Madame Zahra in the kitchen.”

“Yes, sir.”

Campbell entered the cooking area and found Zahra using a Bunsen burner to light what he thought to be one of those Turkish cigarettes. She was tilting her head toward it while holding back her waves of jet-black hair. She straightened up when she got it going. “The Yarmoloviches, they were helpful?”

“No, the Yarmoloviches were not helpful. Let’s forget them for a moment. You started telling me something about being in a trance.”

“Yes.” She went on to explain how she had been conducting a séance with the couple and Kaufman, and was in a trance when the incident occurred. She claimed she saw nothing. Campbell knew the Yarmoloviches were listening; they started whispering to each other as soon as they heard their name.

“I step outside of myself,” Zahra explained to the layman, “and become door through which spirits may pass into this world.”

“Ghosts?”

She smiled. “I know what you are thinking — glowing apparitions, floating in air at end of your bed at night, making voo-ooo sounds. Tales told by ignorant peasants.”

“Yeah,” he said, “I guess that’s what I was thinking.”

Madame Zahra closed her eyes. “One cannot see them, but one can feel their presence. Sometimes they are confused and frightened, like lost children. Other times, like this evening, they want to be heard and they will speak through me.”

Campbell removed his cigar. “Who was speaking through you this evening?”

She opened her eyes. “Rose Kaufman.”

Bickerstaff knocked on the doorframe. “Sir, the wagon’s arrived.”

“Laforet too?”

“It looks that way.”

“I’ll be right back,” said Campbell, “don’t move,” and he stepped out of the kitchen. “Bickerstaff, stay here and keep watch on these three; make sure they remain separated.” Campbell galloped back down the stairs to meet Laforet.

A small crowd had gathered, unfazed by the still-blowing snow and frigid temperatures, fascinated at the sight of a dead body. The doctor, dressed in his Donegal tweed overcoat, cashmere muffler, and a lambswool wedge, was leaning over the victim.

“All right, everyone clear out,” said Campbell. “Go back to your nice warm beds.”

“Detective,” said the doctor.

“Is this how you normally dress for a suicide? Did you stop at Wickham’s on the way over?”

“I always try to look a little livelier than the corpse,” said Laforet, giving Campbell the once-over. He stood up. “So is that what this is? A suicide?”

“I saw him hit the pavement.”

“And he didn’t have any help?”

“What makes you think he might have?”

“I don’t know,” said Laforet, looking down and pointing. “The twist to his body is rather curious. As if he turned, or tried to turn, mid-flight.”

“Too late to change his mind.”

“Did you see him go through the window?”

“No, I didn’t.”

“And yet you’re certain he wasn’t pushed?”

“No one up there could have pushed him, and so far there’s no evidence of anyone else having been in the room at the time. I’m sorry; go on.”

“Well, the twist in the body and the position of the arms suggests to me that he went out the window backwards, and then turned, perhaps instinctively bracing himself for the fall.”

“Possibly. Or, like I said, maybe he changed his mind. It would have all happened in a matter of seconds.” Campbell took one last good look up and down and around the scene and then said, “All right, let’s go upstairs and I’ll introduce you to the cast. Top floor. I can fill you in along the way.”

Laforet turned his gaze up to the third-floor gable.

“You might even have time to read me the city directory.”

In the apartment they found Bickerstaff straddling what had been Kaufman’s chair, now positioned in the middle of the floor, and eyeing the Yarmoloviches, who were still seated at the table. Campbell called in the direction of the beaded curtain. “Madame Zahra, would you come out here please?”

She made her entrance.

“Madame Zahra, Mr. and Mrs. Yarmolovich, this is Dr. Laforet, our city’s coroner and a colleague of mine.”

The doctor removed his hat, walked over to Zahra, took her hand, which she had already extended, and gently grasped her fingers. He then nodded at the Yarmoloviches as he placed his hat on the table and unbuttoned his coat.

Campbell turned to the constable. “Bickerstaff — go down and make sure they don’t need help with the body and then station yourself inside the vestibule. Give me a shout if there’s a problem.”

Bickerstaff touched his hat and made his way back down through the opening in the floor.

Campbell faced the trio but was speaking to Laforet. “Where we left off is with a domestic argument between the late Kaufman and his even later wife, Rose. But,” he said, glancing at the doctor, “there is evidence that Kaufman may have been pushed.”

Madame Zahra remained stoic but the Yarmoloviches vehemently shook their heads. Campbell continued. “Was there anyone else — physically, that is — in this room this evening?” More head shakes. “Madame Zahra, who else lives in this building?”

“Second floor is vacant; main floor is landlord.”

“His name?”

“Old Gravy.”

“Come again?”

“That’s what it sounds like. Old Gravy.”

“O’Grady?” Campbell had no idea where he pulled that one from.

Zahra’s eyes widened and she aimed a finger at Campbell. “Yes, O’Grady. That is his name.”

“He must be a heavy sleeper.”

“He is away. Visiting to Chicago, I think it was.”

“All right,” said Campbell. He sighed and pocketed his pad and pencil. “Speaking of sleep, I think we all could use some.” They all seemed to be losing focus, even the medium.

Laforet donned his wedge and began fastening the long row of buttons on his overcoat.

“Madame Zahra,” said Campbell, “I’ll be back tomorrow morning. Mr. and Mrs. Yarmolovich, I’ll have Constable Bickerstaff escort you home. You can expect to hear from me tomorrow as well. Good night.”

It was an abrupt ending to an abrupt start. Campbell and Laforet left Zahra’s first. Once back on the street, Campbell took a moment to re-examine the scene of Kaufman’s death. Snow was accumulating and the blood that had pooled was now covered in white.

“Any further thoughts?” Campbell asked the doctor.

Laforet was wrapping his muffler around his neck. “I agree that none of them could have propelled him, willingly or not, out of that window. It has to have been a suicide.”

“I need to know more about this man,” said Campbell, looking up at the window. “Do sane people normally do things like this?”

“In my experience, it’s always been sane people who do things like this.”

“And what about this stuff about the spirit world?”

“My spirits come from bottles, Campbell, not Ouija boards. Are you all right?”

“I’m all right. I just need to finish my walk.”