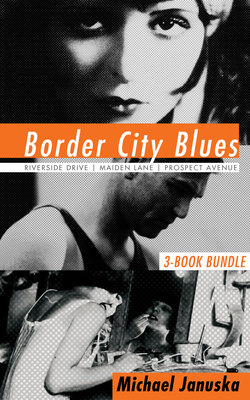

Читать книгу Border City Blues 3-Book Bundle - Michael Januska - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

— Chapter 11 —

ОглавлениеTHE BOILING POINT OF ALCOHOL

Young Bertie Monaghan and his father Jacob were sharing a pitcher of lemonade under the silver maple in their backyard. Mrs. Monaghan was visiting her mother.

‘In the old days we’d hide it in the bush where it wouldn’t draw attention or cause any damage, but in our case,’ Jacob gestured with his thumb, ‘I think the garden shed will do just fine.’

Bertie nodded and tipped his glass to his mouth for another sip. The ice sloshed back and some lemonade dribbled down his chin. He wiped it with the back of his hand. While other boys were getting driving lessons from their dads, Bertie was learning how to make moonshine. It was an old family tradition.

‘We’ll need an oversized kettle for fermenting. It sits on a rack a couple feet off the ground, and the gas burner goes underneath. Gas is the best. Oh — and we’ll need a good thermometer.’

Monaghan took another look over his shoulder to make sure none of his neighbours were about.

‘Now, from a hole at the side of the kettle, right near the bottom, we run a rigid, narrow tube and close it off with a valve. The still is smaller than the kettle and positioned an arm’s length from the rack. Its neck should taper to an opening just large enough to accommodate an end of narrow, flexible pipe. Running out the side of the neck, just above where it connects to the still, is another rigid tube like the one coming out the side of the kettle. Connect the end of this tube to the valve. Together, these tubes should form a straight line parallel to the ground. The pressure of the gases in the kettle will push the liquid along this connection, letting it drip smooth and regular into the still.’

It was difficult to tell who was more excited, Monaghan, who was describing it like it was a magical invention he saw in a dream, or his son, who was taking it all in, agog.

‘Back to the flexible pipe: first, keep in mind that its length will affect the distillation process — the longer the pipe, the weaker the product. Bend the pipe so it points down at a 45-degree angle. Connect a short length of much wider, rigid pipe to the end. This is your condenser. Connect a much smaller tube to the open end of it and run it to whatever vessel you’re using to collect the alcohol, say a good size jug. And we can’t make this tube too short: if the jug is too close to the burner the alcohol will evaporate or explode.’

‘But what do we make the spirits with, dad?’

‘Basically, corn. We pour it into the kettle and then top it with just enough lukewarm water to cover it. Let it breathe for two weeks. After a few days the ferment will start to bubble and stink like shit in a frying pan, so we’ll have to keep the shed well-ventilated.

‘The thermometer is so we can keep the heat at a steady 180 degrees — just above the boiling point of alcohol and below the boiling point of water. When the pressure starts building in the kettle, open the valve until you have a slow drip into the still. Make sure the amount of ferment getting forced into the still is equal to the amount of steam going up the pipe — you don’t want the still to either fill up or boil dry. The steam will condense and then run down the tube into the jug. What we’ve got now is 198-proof ethyl alcohol. It’s filtered through charcoal, and then diluted three parts alcohol to five parts distilled water. If we mess it up, we just keep trying. Every still has its own personality, and you just have to take the time to get to know her.’

That was about ten days ago. Right now Bertie was lying awake in bed like he was waiting for Christmas. He could smell the ferment from his window. He wondered if any of his neighbours on this hot summer night could as well. His dad said that anyone who did could get bought off with a jar.

Mrs. Ferguson had noticed the odour a few days ago when she sat down to her tea. It came wafting in through the dining room window and seemed to be coming from across the alley. She asked her son to confirm her suspicions for her and he did just that.

‘I guess you just never noticed it before, ma.’

‘I know what that smell is. Why hasn’t anyone done anything about it?’

‘Because this family makes good whisky. Now mind your own business, okay?’

Mrs. Ferguson was beside herself. It was a nightmare come true. Could a person really distill whisky in their own backyard without fear of consequence?

‘What is the world coming to, Stannie?’

‘About a buck a quart,’ he cracked.

He was twice her size but that never stopped her from slapping him around a bit for his ‘insolence and sinful behaviour.’ She fetched her rolling pin and started chasing Stannie around the dining room table with it.

‘All right, all right, ma. I won’t be buying any of his stuff. Just please do us both a favour and don’t go to the police.’

That wouldn’t be a problem. Mrs. Ferguson had made her rather poor opinion of the chief constable and his force known to several officers, and they were no longer returning any of her calls. No, Mrs. Ferguson was going to take a different route. She had recently heard of a young officer who was not afraid to do right and uphold the law. And it just so happened she knew a woman, a certain Mrs. Scofield, who was friendly with this boy’s mother. Mrs. Ferguson had made sure she crossed paths with Mrs. Scofield at the Avenue Market earlier this morning.

‘Have I got something to tell you!’

‘You have something to tell me?’

‘Isn’t that what I just said?’

‘Don’t ask me what you said. I’m the one that’s hard of hearing, Mrs. Ferguson. Besides, if you’re not going to pay attention to what you’re saying yourself,’ said Mrs. Scofield, waving an impatient hand, ‘then I’m off.’

‘Oh, Thelma, don’t be like that.’ Mrs. Ferguson touched Mrs. Scofield’s shoulder. ‘I’ve got a neighbour making spirits on his property.’

‘Whisky?’

Mrs. Scofield’s hearing was improving.

‘I’m not sure. It was Stannie told me.’

‘Oh, Stan.’

Mrs. Scofield didn’t care for Stan. She still blamed him for the death of Goldie, her golden retriever. Stan used to take Goldie to the river to swim. She was a good swimmer but one time Goldie dove in and never came back up. Mrs. Scofield said she knew the law. She said Stan should have been charged with negligent canicide.

‘Corn?’

‘How would I know?’ said Mrs. Ferguson as she adjusted the bag hanging from her shoulder. ‘All I do know is we have to put a stop to it.’

‘Yes, we do,’ agreed Mrs. Scofield. “‘How do we do that?’

‘Why, your friend Mrs. Locke, of course.’

‘I don’t follow.’

‘Walk with me, dear.’

Mrs. Ferguson hooked Mrs. Scofield’s arm in hers and dragged her towards the streetcar stop.

‘Are you not an intimate of Mrs. Locke’s?’

‘Yes.’

‘And is not Mrs. Locke the proud mother of Officer Tom Locke of the Windsor Police Department?’

Mrs. Ferguson gave Mrs. Scofield a minute to catch up.

‘You want me to tell Mrs. Locke about Stan?’

Mrs. Scofield’s streetcar pulled up. ‘No, Thelma, I want you to tell her about Mr. Monaghan. He’s the villain making moonshine in his backyard and he’s going to get the whole block inebriated.’

‘Well, then,’ said Mrs. Scofield, ‘you should report it to the police.’

Mrs. Ferguson gave a sigh. ‘You know what a rotten bunch they are. It would be useless. That’s why I want you to talk to Mrs. Locke. I’ve heard good things about her boy. He’s an honest one. And he respects his mother.’

The two ladies eyed the passengers stepping off the streetcar. Mrs. Scofield climbed aboard then turned and said she’d mention it to Mrs. Locke at church.

‘Bless you, Thelma! Our cause is a noble one, dear.’

Walking alongside the streetcar, Mrs. Ferguson followed Mrs. Scofield to her seat.

‘For Goldie!’ cried Mrs. Scofield.

The streetcar was pulling away.

‘What, dear?’

At church this morning Mrs. Scofield elbowed her way through the crowd and got a seat next to Mrs. Locke. When they sat down Mrs. Scofield gave her pitch. Mrs. Locke kept her eye on the minister but listened to Mrs. Scofield. Every once in a while she nodded her long, sour face. The Reverend’s sermon, coincidentally, was on the evils of strong drink. He had the congregation all fired up. Mrs. Locke raised the issue with her son over dinner.

Tom Locke knew the neighbourhood. He parked around the corner from Mrs. Ferguson’s place and made his way silently up the alleyway armed with his trademark baseball bat. No uniform, no badge, and no gun. He recognized the smell right away and honed in on the Monaghan property. In the moonlight he could see that the one window in the shed was recently boarded up and part of the roof was cut away, no doubt for ventilation purposes. He found a shovel in the garden and pried open the flimsy door.

Jacob Monaghan arrived just in time to see a shadowy figure smashing the components to his whisky still, which the assassin had dragged out into the alleyway. The reek of the ferment filled the air and made Monaghan gag.

Locke turned upon hearing his protests. Monaghan was prepared to confront him until he saw the baseball bat and the mad gleam in the swinger’s eye. Monaghan had heard about this fellow, and the word on the street was that he was actually a cop. Locke stopped swinging and pointed his weapon directly at Monaghan. His eyes were blazing and sweat was streaming down his face. To Monaghan, he looked like a man possessed.

“You want some, mister? I’ve got plenty left.”

Monaghan backed off. “No, sir.”

Locke looked around. Lights were coming on in some of the windows facing the alley. There were silhouettes in a few of them. He hoped they all got a good look. Bertie Monaghan sure did. He had his face pressed against his bedroom window, watching. So much for family tradition.