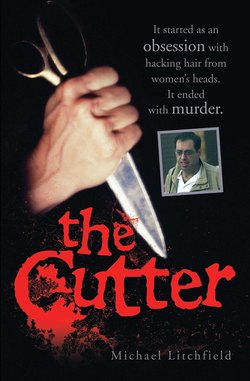

Читать книгу The Cutter - It started as an obsession with hacking hair from women's heads. It ended with murder - Michael Litchfield - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SHATTERED LIVES

ОглавлениеMost people feel safe in their homes; Heather Barnett and her two children most certainly did – a fatal mistake for which there would be no second chance.

Heather, at the age of 48, had built up a reputation as a skilled seamstress. Self-employed, there was no shortage of work. People from all over the county of Dorset came to her with sewing jobs – from repairing curtains and shortening trousers to making dresses for weddings and other special occasions. She was a consummate professional with a keen eye for detail and an artistic temperament; a perfectionist in all that she undertook, but especially as a mother.

As you would expect, her home in Capstone Road, Bournemouth, was always tidy and cosy. She had made most of the curtains, cushions, tablecloths and furniture covers – also many of her daughter’s clothes. Her children – Terry, aged 14, and Caitlin, three years younger than her brother, though equally mature intellectually – were always smartly turned out; they were Heather’s pride and joy. Any patching of their clothes was cleverly camouflaged. The children’s friends often asked Heather to mend their frayed jackets or snagged leggings and she always obliged smilingly. Being a caring mother and a friend to her children and their companions was more important to her than anything else.

Most days she would be fielding phone calls incessantly from regular customers and others who had just heard about her services. Increasingly important to her as a single mother, her cottage industry flourished on the most effective form of advertising – word of mouth.

Tuesday, 12 November 2002 dawned overcast and chilly. Bleak winter was in the air, even in Bournemouth, a coastal town renowned for its relatively mild climate. The weekday morning ritual was in full swing by 8.00am in the Barnett household: territorial fights over the bathroom, squabbles over countless petty issues, the usual brother versus sister friction, and breakfast on the run. A peck on the cheek for mum and jaunty waves as Heather dropped off the children at Summerbee School in Mallard Road at just after 8.30am.

‘Be careful,’ said Heather, as her children scrambled from the car. How ironic that her last words to her children were a caution to them.

Bournemouth was a busy town, with rush-hour gridlock to match any city. Commuters battling against the clock made roads hazardous, especially on a wet morning like that Tuesday. The pavements were scarcely any safer, having been turned into rat-runs by cyclists seeking refuge from aggressively-driven vehicles. A CCTV camera, attached to the Richmond Arms pub in Charminster Road, filmed Heather’s white Fiat Punto turning into Capstone Road at 8.37am.

Heather had a daily routine. As soon as her children were at school, she would sit in the kitchen at home with a cup of tea, possibly nibbling a round of toast as she listed her schedule for the day in order of priority. There were costumes to be made for other children’s Christmas concerts and school plays; although not desperately urgent, she preferred to keep ahead of the game, if possible, rather than having to play catch-up, which was always stressful. Self-discipline was one of her business strengths.

There was already more than enough stress in her life with the demands of bringing up two children alone on limited resources. Not that Heather was a person to complain. She was more than happy with her lifestyle and considered herself fortunate to have such well-balanced and responsible children. She was optimistic about their future. She talked with motherly pride to friends and neighbours about Terry and Caitlin, especially with reference to their progress at school and how, despite difficult times ahead for job-seekers, she was convinced her children would be trailblazers in whatever careers they chose. In many respects, she was a mum on a mission.

Although the family did not want for anything, Heather, just like any other single parent, needed to keep a watchful eye on the budget. Any sudden, unexpected, sizeable expense was capable of knocking their economy off kilter. Nevertheless, the future looked rosy that November morning, despite the swiftly gathering clouds.

Commissions were coming in and Heather had even begun to plan for a bumper Christmas. She had already started a provisional list of Christmas presents to buy – mainly for her children. She liked to be organised; it was good for business, demonstrating to customers that she was professional and no dilettante. It also boosted her confidence, making her feel in control of her own destiny – the kind of fool’s paradise we all cocoon ourselves in, though few of us, fortunately, pay so dearly for our one-dimensional faith in self-determination.

After breakfast, she took a few phone calls but did not make any. The only call made that day from Heather’s landline was at 5.53am that morning. Heather had been an early riser all her adult life and was a great believer in hitting every day on the run. She was very much a morning person, so typical of people born and raised in the country, well away from cities and urban sprawls. ‘It’s the early bird that catches the worm’ was one of her favourite maxims.

Everything in her life was so normal that Tuesday morning. No alarm bells or portent of the seismic events just around the corner. Known by one person only, the countdown towards oblivion had already begun. Without warning, without a chance to take avoiding action, without prior threats, death came cold-calling with a knock on the front door, probably a few minutes before 9.30am.

* * *

Now fast-forward the clock to mid-afternoon of the same day.

Terry and Caitlin left school shortly after 3.30pm and walked home together as usual. Their mother’s car was parked in the drive. Everything appeared routine and normal so far. Their modest but comfortable home was the ground-floor flat and they made their way to the side of the house, where the entrance was situated.

Caitlin tried the door; it was unlocked. She opened it and skipped inside, happy to be home, as always. Another day of school over; always something to be celebrated! Going into the house ahead of her brother was yet another little afternoon ritual, a gesture of old-fashioned respect – ladies first.

As soon as Terry had closed the front door behind him, Caitlin called to her mother, something else she always did on their return from school. There was no answer. Strange, thought Caitlin, especially as the car was outside. Heather always liked to be indoors to greet them with a hug, kisses and eager questions about their day at school. If there was any shopping to be done, she tried to do it in the morning.

Terry thought his mother might be in the garden. However, almost immediately, he was overcome by an uneasy feeling that something was wrong. ‘There was a big silence,’ he would later tell the police. ‘I didn’t like it.’ The silence was eerie and seemed to engulf and swallow up the pair of them. Unlike the comforting and peaceful silence of a church or cathedral, this was brooding and malevolent.

Terry noticed that the bathroom door was closed. Caitlin knocked on it, saying, ‘Mum! Are you in there … Mum?’ Silence still. Creepy silence. So she tentatively inched open the door.

Theirs was a home of laughter and fun. A good-to-be-alive home. Whatever was happening outside, within their four walls the sun always shone, even on miserable, damp November days like this one. Not any more, though. In the next few seconds, everything for those two children was to change for ever.

Terry and Caitlin were far too young, of course, to have seen the classic Alfred Hitchcock movie Psycho, but for an older generation the gore that confronted these children would have triggered violent images of Janet Leigh and a bloodbath in a shower.

Heather Barnett had not gone out. She was on the bathroom floor in a pool of blood. Her legs were straight and her left hand rested beside her body. Her right hand had been placed on her lower stomach, a clump of light-brown hair grasped in the palm of her hand. About 30 human hairs, of a different colour to hers, were in her other hand. Her upper clothes had been pulled up to the level of her breasts, while her jeans had been unfastened and pulled down slightly, exposing the top of her pubic hair. Her bra had been snapped at the front between the two cups. Both breasts had been cut off and lay on the floor beside her head. Her throat had been cut ear to ear, the wound gaping to the extent that her spine was exposed. There was also a palpable injury to the top of her head.

Heather’s head and shoulders lay in a pool of blood. A trail of this same oozing red liquid led from the workroom, through the lounge, to the bathroom. Further bloodstains and smears were noted on various surfaces at around waist-level, near an upturned stool, adjacent to the patio doors in the workroom.

But the sight the children will remember to their own dying day was that of their mother’s butchered breasts. Each one had been sliced off and placed beside Heather’s head on the floor.

Seconds later, they were in the street again, this time dashing into the road, running up and down in a daze like headless chickens, flailing their arms, stopping traffic and pedestrians, their screams muted, shock paralysing their vocal cords.

Breaking away from his sister, Terry stumbled back into the flat to make a breathless 999 emergency call, willing his voice not to desert him again. His call was answered almost immediately.

‘My mum’s just been murdered!’ he blurted, his voice strong again, but tortured. He was no fool. He knew there was no life left in his mother and that this carnage was in no way the result of an accident.

The telephone operator tried to calm Terry, who, fearing that he might not be taken seriously, felt it necessary to add, ‘This isn’t a joke. She is dead.’

Trained to deal with these situations, though mercifully they were only rarely of such depravity, the operator knew the importance of keeping the line open for as long as possible, so that all the priority information could be elicited from the caller, simultaneously noting the time that was on her screen.

Often callers caught up in tragic circumstances who are hysterical or panicking can hang up before providing all the necessary information. All 999s are automatically recorded to enable the police later to hear exactly what has been said when a crime or accident was first reported. A caller claiming to have been genuinely panicking, for example, when making a 999 call might be found to lack the ring of truth when played in court months later to a jury. Therefore, operators who field 999 calls are trained to remain calm and logical, but clearly directive in their questioning, in order to elicit essential information as efficiently and as accurately as possible.

Despite the harrowing situation he was caught up in, Terry managed to keep his head while on the phone, but quickly went to pieces afterwards as shock kicked in.

Terry joined his sister in the street, where a couple were just pulling up opposite their house. The woman in the car was Fiamma Marsango, who lived at 93 Capstone Road, and she was accompanied by her future husband, Danilo Restivo, an Italian, who had moved in with her a few months earlier.

Terry beckoned frantically to the woman, pleading with her to come to them. Fiamma wondered what on earth was going on. As another neighbour said, ‘When children are running about shouting, “Murder!” it takes some while to compute. It’s the last thing in the world you’re expecting to hear and you don’t, at first, take it seriously. You start looking around for the tell-tale signs of something like Candid Camera. Murder comes to other people, to other streets, not your own.’

Restivo went with Fiamma to the children. The staccato, disjointed and muddled narrative, naturally devoid of chronology, that spilled from the children appalled Fiamma. ‘You poor children,’ she muttered. ‘Have you called the police?’

‘Yes, yes,’ Terry said tearfully.

Sobbing uncontrollably, Caitlin held her head in her hands, the tears dripping on to the road, her entire body shaking in shock.

Restivo put his arms around both children, pulling them into him, hugging them tight.

‘Come with us,’ said Fiamma. ‘Don’t go back into your home. Come with us to wait for the police.’

Restivo assured Terry and Caitlin that they would be safe with them. Still with his arms around the children, he guided them into number 93.

Another passer-by who tried to console Heather’s children also made a 999 call. By then, however, the emergency services – police and paramedics – were already on their way. Grief-stricken, the children were now inconsolable – shivering, sobbing, muttering incoherently, trying desperately to convince themselves that this was not happening.

Little groups were gathering on both pavements. Most of the people were casually interested, keen to discover the cause of the commotion, and shocked when scant news of the discovery filtered through. They were most concerned for Terry and Caitlin, whose distress had been obvious. And yet none of them was aware at this point of the full horror of the situation and the traumatic sight that had greeted the children. Very sensibly, none of the bystanders had ventured into the house. Natural instinct might have been to rush into the flat to try to administer first-aid and revive Heather, but Terry’s graphic account, albeit brief and fragmented, had been sufficiently succinct to ward off any aspiring Good Samaritan. Probably also on their minds was the fear that, if Heather had indeed been brutally murdered, her killer could still be on the premises.

People always complain of the ‘agonising wait’ for an ambulance and the police, but it is rarely as long as imagined. In life-and-death crises, the perception of time has a tendency to become distorted; similarly here, the reality of time had little meaning for the bystanders or the traumatised children.

‘Where are they? They’re not coming. No one’s coming!’ Terry despaired. ‘They didn’t believe me. They thought I was fooling around. I knew it!’

But the wail of distant sirens soon confirmed that the emergency services were indeed on their way. Still, it seemed ‘an age’ to those waiting before the fleet of police cars and an ambulance stopped in a squeal of brakes outside the house. And with them, one of the most baffling murder hunts in the history of modern crime was about to begin.

From this moment, police procedure took over. As soon as the first police officers at the house had confirmed that Heather Barnett had been unlawfully killed, the entire road was declared a crime scene and secured. No one would be allowed to contaminate evidence. A police doctor was called out, the coroner’s office was informed, and specialist scene-of-crime officers were despatched by the van-load.

The response to a crime of this nature is swift and involves massive manpower and resources. Everything happens fast at first. This is essential because all statistics demonstrate that if a murder is not solved within the first 48 hours, the odds of a successful conclusion diminish proportionately by the day.

Other statistical factors also strongly influence the attitudes and procedures of the police at the outset of any murder investigation. The vast majority of all murders are committed by someone the victims know, maybe even live and share a bed with – a spouse, a lover, a former husband, a jealous work colleague or maybe even an ‘ex’. The police cannot ignore these known factors. They are foremost in the thinking of all detectives because they are so often signposts to a swift and tidy conclusion.

So, despite the visual message from the bathroom of Heather Barnett’s flat, it was imperative that the police began by following the tried and tested methods of inquiry, and sticking with the conventional route until forced to look elsewhere. As detection methods have advanced, so killers have become increasingly cunning in an effort to keep ahead of the latest scientific breakthroughs. Some killers, for example, try to make their victim appear to have been the random target of a mugger, perhaps killed during a handbag snatch, simply having been in the wrong place at the wrong time. All these possibilities and permutations would have been part of the thinking of detectives who were quickly drafted in to get the macabre ‘circus’ rolling.

A fine balance had to be struck in handling the two children. They were in extreme shock, and distraught, naturally. What they had just seen would be engraved on their memories for the rest of their lives.

In one sense, the children were now the priority. How they were handled and cared for – in the immediate aftermath of the tragedy and in the days and weeks to come – was of utmost importance. But they had found the body; they may have been the last people to see their mother alive, apart from the killer. Therefore they were vital witnesses. They had to be questioned. Their testimonies would have to be gently tested for flaws and inconsistencies.

Specialists from the police Child Protection Unit were sent for. Intimate questions had to be asked about the domestic situation. Where was their father? Who else lived there? Who, if anyone, was missing? Had Heather Barnett been involved in a dispute recently with neighbours or relatives? With a man or a woman? Had she been threatened? All these harsh questions had to be put to Terry and Caitlin. All murder investigations are time-sensitive and these questions could not be postponed.

Even before hearing the recording of Terry’s desperate and shocking 999 call, his exact words had been relayed to the police by the operator, which included the phrase ‘My mum has just been murdered.’ On arrival, police found that Mrs Barnett was already cold to the touch. Rigor mortis had begun.

Unless there were special climatic factors, rigor mortis would usually begin about thirty minutes to three hours after death. This stiffening process begins with the eyelids, neck and jaw. The route is always the same – top to bottom – and takes between eight to twelve hours to complete. This rigidity continues for about 18 hours and then starts to recede. The ‘thawing’ process can take up to 12 hours, although it might be considerably quicker. In freezing temperatures, though, rigor mortis frequently never occurs.

Rigor mortis had a firm hold of Heather Barnett’s body when the first police officers arrived on the scene, confirming that, in all probability, she had been dead for at least three hours.

Police photographers not only captured for posterity the grisly scene in the bathroom, but also snapped photographs of every room in the flat and also of the scene outside, including that of the little groups of curious onlookers. Arsonists have been known to derive a great deal of gratification from watching a blaze they had started. Equally, certain types of murderers continue to return time and again to the scenes of their crimes. They have been known to attend the funerals of their victims or to visit the graves. So there was always the chance that Heather’s killer was out there in the street, pretending to be horrified, wanting to cosset the children, yet all the time secretly thrilled by his achievement. During the next few days, the police would examine all those photographs, looking for anything or anyone who stood out as being odd or out of place – male or female.

The pathologist who went to Heather’s flat carried only two instruments – a pen and notebook. Anything else that he and forensic detectives required was provided by the crime-scene manager, the United Kingdom’s equivalent to a medical examiner in the USA. The assortment of accoutrements routinely taken to a suspicious death by a crime-scene manager were containers for ‘bottling’ evidence, swabs for collecting fluid samples, and a thermometer.

Although the cause of death seemed blindingly obvious in this case, it would not be formally recorded until a postmortem examination had been completed. It was not uncommon, for example, for the apparent victim of a fire to be found with a bullet in the head when examined later in the path lab.

Top of the medical agenda here was to try to establish, as accurately as possible, the time of death: the reason for so much initial focus on Terry’s phone message. In respect of getting a reliable handle on the time of Heather’s death, the police had some useful reference points. The children had left for school at around 8.30am; they were home by 4.00pm. Rigor mortis was taking a firm grip, so 9.30am seemed a rational estimate; a combination of scientific deduction and educated guesswork. This aspect of a murder investigation can never be exact, unless there was an eye-witness to the actual killing – a rare occurrence.

The temperature of the corpse was measured with a rectal thermometer. In a normal environment, such as Heather’s flat on a day in early winter, the temperature of her internal organs would be expected to decrease by around 0.8 degrees Centigrade (1.5 degrees Fahrenheit) every hour.

Heather’s partially clothed body had been left undisturbed in the position in which she had been found by her children until the gruesome portfolio of pictures had been taken. The next nagging question was where had she actually died? She had ended up in her bathroom, but was that the location where her heart had actually stopped beating? For the investigators, this was another crucial issue.

The ‘A’ team was assembling by the minute. Some of the country’s top specialists in their particular field of criminal investigation were already there. Others, from near and far, would soon be joining the investigation. Later, it would become an international operation, with investigative tendrils reaching out to every corner of the globe. For now, though, these highly trained men and women were ticking boxes, going through the clichéd routine almost by rote, unaware that they were beginning a roller-coaster ride that would test their collective expertise – as well as their stamina – to the limit for the next eight frustrating years.

The pathologist needed to examine Heather’s body thoroughly before it was removed. Gravity dictated where the blood would settle after death. If a body was lying on its right side, for example, lividity (a purple-blue hue) would discolour the shoulder, arm, hip and leg on that side. So if the right side of the corpse was bluish, but it was lying to the left, the inference would be that the body had been moved. Bacteria invaded cadavers, endowing them with a greenish tint, but that did not occur until 48 hours afterwards, so obviously this was not something to be expected.

The carnage that November afternoon, coupled with the devastation of two children, who had witnessed the stomach-churning injuries to their mother, reduced veteran officers to tears.

However, one vital piece of evidence – much, much more than a mere crumb of comfort – convinced them that they would soon have the killer in their sights.

Sometimes, at the moment of violent death, the victim would clutch something, possibly a defensive weapon, and it would remain clasped in the hand. This clenched fist around an object after death was known as a ‘cadaveric spasm’, termed a ‘death-grip’ by pathologists. This was usually the result of superhuman exertion, fuelled by an adrenalin surge, characteristically when someone was fighting – or running – for their life. This sort of speeded-up rigor mortis was notorious for throwing the time-sequence out of sync. Without all the other factors, this was one element of this case that might have skewed the estimated time of death.

Gripped tightly in Heather’s right hand was a small amount of human hair, retained in her grasp by cadaveric spasm. In the last desperate moment of her life, as she fought to save herself, had she wrenched the hair from her attacker’s head? Maybe it was that final retaliatory act of hers that had driven her assailant to such acts of inhuman sadism. If so, surely there would be such a surfeit of DNA evidence that the perpetrator would be in the net within days.

That was the mood of the investigators in Capstone Road, Bournemouth, on day one of this investigation. With such a convincing piece of evidence, the smart money was on a swift and brutally efficient manhunt and conviction.

They were wrong, of course. Completely and utterly wrong.