Читать книгу The Mural - Michael Mallory - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER FOUR

The tall trees blocked out a good portion of the sun, making it seem much darker, though Jack was relieved that the misty fog that had made yesterday’s visit to the woods so uncomfortable had gone. He and Dani Lindstrom had bumped and bounced their way to the spot where the road was blocked by the fallen tree and then got out. “We’ll have to fight our way through a tangle of brush a ways up,” Jack told her, “so I hope you’re not wearing anything delicate.”

“I left my chiffon prom dress back at the motel,” Dani said, grinning.

The hike seemed easier this time, perhaps because Jack knew where he was going, though the new day revealed nothing that Jack had not noticed before. The city hall building was now more visible from other parts of the ghost town, but that could be attributed to the lack of fog. Jack snapped pictures all the way along as they hiked into the main part of the village. Once they had reached the city hall, Dani said: “Wow, look at this place.” She started to trot up the steps, but Jack stopped her.

“There’s no light in there,” he said, pulling out his flashlight, “and you have to be really careful. Debris is everywhere.” Holding the light in front of him, he crept inside, while Dani followed.

“This is like a mausoleum,” she commented, her voice echoing in the large empty building.

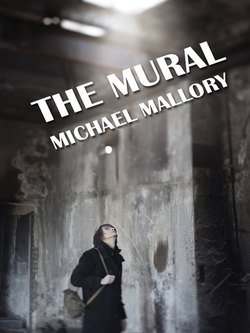

Jack shined the light on the back wall. “There. You can make out a woman’s face.”

Dani moved closer to it. “She doesn’t look very happy.”

“I hadn’t noticed that before, but you’re right.” Jack started snapping a few more shots of the exposed part of the mural. In today’s light the face did appear to be in some sort of discomfort, even pain.

Dani reached out and touched the dull gray overcoat. “Why do you suppose they painted over it?”

“Maybe all the figures looked unhappy,” Jack said, checking his last picture on the tiny digital screen. “Maybe the effect of the mural on the viewer was depressing, something people back then didn’t need.”

Dani continued to explore the wall with her fingers. She pulled off a loose gray flake which revealed more of the picture. She touched the painted image, but pulled her hand back, like the wall was hot. “This is wet!”

“That’s not surprising,” Jack said. “It’s been exposed to the elements for quite some time.”

“Not the wall, Jack, the paint itself.” Dani held up her hand to the flashlight beam, and revealed smudges of reddish-brown on her fingers. “How can the paint still be wet?”

“Certain kinds of paints take forever to dry, particularly if the pigment is not properly mixed with the base. The moisture in the wall might have so permeated the paint layer that it has combined with the pigment.” He reached into his back pocket and pulled out a handkerchief, and tossed it to her so she could wipe the paint off her finger.

“Do you really believe that?” she asked, blotting her hand.

“Why wouldn’t I? Why else would it be wet?”

In the dim light, Dani examined her stained index finger and then said: “Don’t you feel it, Jack?”

“Feel what?”

“Don’t you sense that something just isn’t right here?”

Jack smiled. “Ruined buildings sometimes have that effect on people. You said it yourself: this place is like a mausoleum.”

“Jack, let’s get out of here, okay?” Dani said.

“Sure. Let me take one more shot of the face in the mural, for safety, and then we’ll go.”

“Hurry, please.”

As Jack stepped over to the wall, camera in hand, he told himself that this was exactly why he was reluctant to let Dani in here. Like most people, she viewed a building as some kind of living thing. A house with lights and a family living in it was full of life; a house with no lights, no family, no human activity, was somehow “dead,” and therefore creepy. While he had grown accustomed to the sentiment, because it was so common, he could not accept it himself. A building was a building, period. A foundation, floors, walls, and a roof, none of which were inherently alive. Buildings were erected by men, maintained by men, and demolished by men.

Buildings did not have souls.

Jack crouched slightly to get a good eye-level view of the woman’s painted face and snapped the flash, then checked it to make sure he had it. But before stepping back, he reached out and lightly touched the image. Dani had been right, the paint was wet. Perhaps it had been improperly done, and had started to deteriorate, so was covered up. Maybe it was never even finished.

“Jack?”

“I’m coming, let’s go.”

Whatever bad vibe Dani was feeling inside the city hall abated with each step she took back to Jack’s pickup. “You’re going back to L.A. today, right?” she asked, climbing into the passenger seat.

“As soon as I drop you off at the motel,” he said, closing the driver’s door, but not starting the engine.

“I think I’m going to miss you.”

Jack desperately tried to think of a soothing, polite lie, but could not. “Truth be told, I think I’m going to miss you, too.”

Her green eyes drew him toward her. He tried to fight it, but could not.

“Dani, I’m not going to lie to you,” Jack said, leaning closer to her face, her body. “I’m attracted as hell to you.” His breathing was getting heavier, deeper. “When you climbed into that Jacuzzi with me last night, what were you thinking? Be honest.”

Her lips parted. “My first thought was, ‘Maybe I should go over there and take that guy and drag him back to my room and give him the screwing of his life, because I now can. I’m free. And I want to see if I still have it.’”

Jack swallowed hard. It seemed like the temperature inside the pickup cab was rapidly rising.

“Then I saw the expression on your face. You looked so happy, and you said you were thinking about your little girl, and I realized you didn’t deserve to be led on, rolled, and dumped, just because I’m pissed at my ex. Okay, my soul’s bared. Now it’s your turn. Did you want to come to my room last night?”

“Hell, yes.”

“Why didn’t you?”

Jack sighed. “Maybe I’m all thought and no follow-through. Maybe that’s why my wife is more successful than I am.”

“Do you still love her?”

“Don’t ask hard questions.”

“How about me, Jack?” Slowly, deliberately, she started unbuttoning her blouse. “Do you love me?” She slid her blouse completely off. “Or is that a hard question, too?” With one smooth move, she pulled her bra up over her head, revealing flawless breasts.

Jack tore his shirt off so violently he lost a couple of buttons.

They were on each other like vampires. Alone, in the middle of the woods, unseen by anything human, they tore the rest of their clothes off and made wild, head-banging love in the driver’s seat of Jack’s pickup. Dani straddled him, her back pressed against the steering wheel, and Jack feeling the bounce of the truck with each and every thrust. After both had climaxed, they held each other, Jack still inside her, Dani’s sweat-covered breasts both warming and cooling his chest. Finally, Jack panted: “What do we do now?”

“More of the same, if you’re up to it.”

“I mean in the long run. I don’t want to leave you. But I have to.”

“Something will bring us back together. We’ll find a way.” She began wiggling in his lap, and ten minutes later they were both once more crying out in ecstasy.

It took another hour for them to separate and get their clothes back on. For Jack, it was a revelation; the intensity of the sex had been something he had never felt before. Somewhat shakily, he started the truck back up and drove onto the highway.

After a few silent miles, Dani started to giggle. “You need me to sew some buttons back on your shirt before you go?”

“I’ll just change shirts, but thanks.”

“Won’t your wife become suspicious when she does the laundry?”

“Elley doesn’t do the laundry. We have a housekeeper.”

She reached over and began to massage his chest under his open, buttonless shirt, hardening his nipples.

They barely made it back to the hotel in time.

Literally running to Jack’s room, they made love once on the bed, once on the floor, and finally in the shower. It was there, with the hot water streaming down their linked bodies that Jack asked her: “How much longer are you planning to stay here?”

“Another couple of days. I might hang around longer and see if there are any local historical societies before heading back down to San Diego. If you want, I can see if anyone knows anything about your mural, or the old city.”

“I’d hate to put you to any trouble.”

She slowly knelt down, following the contour of his body with her tongue. “I think I’d enjoy it,” she said.

“There’s nothing left,” Jack moaned as she took him in her mouth.

He was wrong.

* * * * * * *

Several hundred miles away, Marcus Broarty leaned back in his executive office chair and scored a paper ball hoop in the circular file. Seconds earlier the ball had been a follow-up thank you letter from some hungry kid he had interviewed last week. He could not even remember the kid’s name, which did not make much difference, since he was not planning on hiring him. Job-hunters annoyed him. They were nothing but street beggars with neckties instead of cardboard signs, wandering around from company to company pleading for a chance to impress you with their “accomplishments,” then following-up any meeting with the kind of brownnosing missive that he had just used to score two cosmic points. He had never stooped to that sort of thing. His MBA was his ticket. Some of the pricks around here thought it was simply because his aunt was the wife of the chairman of Crane Commercial Building Engineering, but Marcus knew better. He still had to prove that he had the executive stuff after he was installed.

His firing of the man who wrote MBA: Marc Broarty, Asshole on one of the washroom walls was just one example of his strength. Ditto for the miserable little shit that came up with the joke, “What’s the sound of a buzzard vomiting? BROOOOOOOARTY!”

The intercom on Marc Broarty’s desk buzzed. Pressing it, he said, “Yeah, babe.”

“Mr. McMenamin is on line two,” Yolanda’s voice said.

What the hell does he want now? “Oh, god, tell him I’m...no, no, that’s okay, Yolanda, I’ll take it.” Wrapping pudgy fingers around the receiver, he put it to his ear and jabbed the button. “Emac, how the hell are you? I was thinking about giving you a call.”

“I’m here now,” Egon McMenamin said at the other end of the line, and since he was using the speakerphone, he was likely not alone in his office. “I was wondering if you’d heard back from your guy up at the site yet.”

“I don’t have his official report yet,” Broarty answered. “He’ll be in the office tomorrow. I’ll get him on the stick as he gets back.”

“Well, Marc, I could really use some information now, even if it’s preliminary, anything you’ve got.”

“Sounds like you’re in kind of a rush.”

“Not me, Marc, the board. Can’t you call your guy?”

“I suppose I could,” Broarty said, “though when I talked to him yesterday—”

“Oh, you’ve already spoken with him, then,” Emac said.

“Well, yes, but he had not completed his review at the time, and—”

“Marcus, I’m going to confide in you. It looks like the budget on this project is going to be revised downward, so I need to be able to report back absolutely everything that can be salvaged.”

Broarty took a deep breath. “Well, the thing is, Emac, it’s starting to look like the buildings out there might need a lot of work.”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning, um, all this is based on an unconfirmed early report, you understand, but, well, the conditions of the structures apparently aren’t what I’d call great.”

“I need you to be a little more specific than that, Marc,” Emac said. “If they aren’t great, what are they? Good? Satisfactory? What?”

Broarty started to perspire. “Well, we might be in a situation where it could take a lot of work for the houses to be brought up to code—”

“What code are we talking about?”

“Uh, you know, the building and sa—”

“Jesus, Marc, don’t tell me you people are using the building codes of Los Angeles to judge those structures by,” Emac snapped. “Most of the castles in Europe couldn’t meet L.A. standards.”

Rivulets of sweat were running down Broarty’s temples. “I’m sure Jack Hayden is taking that into account,” he said. At least Broarty hoped to hell Hayden was taking it into account, since this was the first time he had stopped to consider such matters.

“I hope he does, Marcus, because I’d hate to think that we engaged a firm that didn’t have a complete grasp of the requirements of the job.”

“Emac, Emac, c’mon, you know we’re here for you.”

“I’d like to think so, but what I’m hearing from you is a lot of vagaries. I have to go into a meeting this afternoon with the men who are paying my salary and your fee for working on this particular project, and I have to be able to tell them either that the Lost Pines Resort development is completely within reach and on track, or that it is going to be prohibitively expense and they should pull the plug. Now which is it?”

“Emac, those are kind of extreme choices, aren’t they?” Broarty said. “I mean, isn’t there something in the middle?”

There was a brief pause before Egon McMenamin replied, “You want option number three, Mr. Broarty? Here it is: that Resort Partners severs its contract with Crane immediately and sues to recoup the moneys already allotted, and then hires another inspection firm that understands what’s at stake and knows what the hell they’re doing.”

Shit! Broarty had glanced at the photos Hayden had sent but had not studied them. Frankly, he was hoping to stay out of this altogether, except to sign his name on the cover letter of Hayden’s report.

“I’m sorry, Marc,” Emac was saying, “but I didn’t hear your reply.”

Broarty coughed. “Actually, Hayden is supposed to be in the office first thing tomorrow mor—”

“Jesus, Marc, who’s in charge down there? Hayden or you?”

“What do you want? Do you want me to sign off on the buildings as they stand?”

“What I want is for you to tell me whether our goal of rehabilitating the existing town is doable. If you sincerely believe it is not, Marc, based on your expertise, then for Christ’s sake tell me. I’d be disappointed, as would the board, but I would accept it. I would, however, hate to find out later that it was a judgment based on faulty information, just like I would hate to offer a good report to the board and then find out that’s not true either.”

Broarty’s head was spinning. Jack had emailed something to him, presumably photos of the place, but he had not actually looked at them yet. Hayden’s the one who should be dealing with this. But Jack was not back, and the decision, like it or not, was his to make. “First, Emac, I want you to understand that I have not personally been to the site. I do, however, trust Jack Hayden’s judgment implicitly, and based upon the very sketchy details he has sent down, prior to his arrival back at the office and the filing of his report, I think you should be able to reach your goal.”

“So that means I can go to the board and assure them that based on your inspection the plans to rehabilitate the structures in the town are both sound and cost effective.”

Marcus Broarty closed his eyes and said: “Yes.”

“That’s all I wanted to know, Marc,” Emac said, his voice suddenly cheerful. “That wasn’t so hard, was it? Send along that full report as soon as you can.”

“You can be sure of it.”

After a few lame pleasantries, the two men hung up. Broarty replaced the receiver with one hand mopped his brow with the other. Then he turned to his computer and pulled up the emailed photos Hayden had sent him, this time really studying them. By the third one, Marcus Broarty’s stomach felt like a chunk of dry ice had lodged in it. Picture after picture showed ruins of buildings and still-standing structures far beyond redemption, except for the city hall structure. Christ, what was he going to do now? He could hardly call Emac back and tell him that he had bluffed his way to a decision that turned out to be the wrong one.

There was only one thing to do.

Broarty pulled up the file on his computer to which he had saved the images and, one by one, began deleting them, sight unseen, as though he had never gotten them. When he was finished, he would go back in and delete Jack’s email as well. This would be his story: he had talked to Jack, but had never received his photos. As for Hayden’s verbal communication to him, well, verbal communication wasn’t worth the paper it was written on. Besides, what was the last thing that Jack said? That he was going to investigate further and hopefully find something more encouraging? The word encouraging was good enough for Broarty.

If the shit really did hit the fan, though, there was always the fact that Jack, if office parties were any indication, was a drinker, so his judgment could be impeached.

You mean you sent a drunk out to do the inspection? Broarty could hear Emac’s snap.

Of course I knew about Jack’s problem, he’d reply, but his work in the past, before his drinking got out of control, had always been professional, and, well, I believe in giving people every chance possible. That’s just the kind of manager I am. But of course, in light of this situation, he will be fired immediately.

Whatever Jack might say in protest would have to be taken against Broarty’s own word; the testimony of a goddamned drunk versus that of an MBA.

He was starting to feel better as he continued eradicating his system of the photos, finally coming to the last one. On a whim, this one he opened, and was surprised to see the face of a woman, turned out so that she appeared to be facing him directly, looking straight into his eyes, if not his soul. She appeared to smile at him. Goddamn Hayden! Broarty thought, grinning at his computer screen, he emailed the wrong pictures in the first place! Jack was supposed to be photographing buildings, not paintings, or whatever the hell this was. “Goodbye, my dear,” Marc Broarty said softly, as he tapped the mouse to delete it, and in a flash, it was gone.

No more evidence.

Broarty sat back in his chair and took a deep breath. Things were going to work out, he felt confident of that. He had protected himself.

He was about to get up and go to the washroom to freshen up, when he looked back at his computer screen and noticed that the image of the painted woman was still there. “That’s odd,” he muttered. Perhaps Hayden had sent two shots of the painting and he had not noticed before now. Aligning his cursor to the corner of the image, he selected Delete and clicked again. Then his head snapped back.

Broarty sat looking at the empty screen for a few seconds, then chuckled. A digital glitch; that was all it was. When he keyed for the image to be deleted, some pixels shifted right before it disappeared.

How else could he explain the illusion that the woman in the painting had just winked at him?