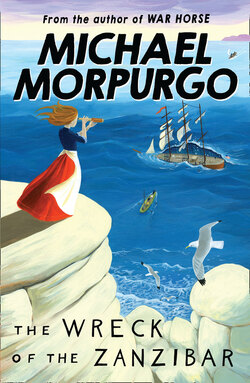

Читать книгу The Wreck of the Zanzibar - Michael Morpurgo - Страница 10

FEBRUARY 12TH

The Night of the Storm

ОглавлениеA TERRIBLE STORM LAST NIGHT AND THE PINE tree at the bottom of the garden came down, missing the hen-house by a whisker. The wind was so loud we never even heard it fall. I’m sure the hens did. We’ve lost more slates off the roof above Billy’s room. But we were lucky. The end of Granny May’s roof has gone completely. It just lifted off in the night. It’s sitting lopsided across her escallonia hedge. Father’s been up there all day trying to do what he can to keep the rain out. Everyone would be there helping, but there isn’t a building on the island that hasn’t been battered. Granny May just sat down in her kitchen all day and shook her head. She wouldn’t come away. She kept saying she’ll never be able to pay for a new roof and where will she go and what will she do? We stayed with her, Mother and me, giving her cups of tea and telling her it will be all right.

‘Something’ll turn up,’ Mother said. She’s always saying that. When Father gets all inside himself and miserable and silent, when the cows aren’t milking well, when he can’t afford the timber to build his boats, she always says, ‘Don’t worry, something’ll turn up.’

She never says it to me because she knows I won’t believe her. I won’t believe her because I know she doesn’t believe it herself. She just says it to make him feel better. She just hopes it’ll come true. Still, it must have made Granny May feel better. She was her old self again this evening, talking away happily to herself. Everyone on the island calls her a mad old stick. But she’s not really mad. She’s just old and a bit forgetful. She does talk to herself, but then she’s lived alone most of her life, so it’s not surprising really. I love her because she’s my granny, because she loves me, and because she shows it. Mother has persuaded her to come and stay for a bit until she can move back into her house again.

Billy’s in trouble again. He went off to St Mary’s without telling anyone. He was gone all day. When he got back this evening he never said a word to me or Granny May. Father buttoned his lip for as long as he could. It’s always been the same with Father and Billy. They set each other off. They always have. It’s Billy’s fault really, most of the time anyway. He starts it. He does things without thinking. He says things without thinking. And Father’s like a squall. He seems calm and quiet one moment and then . . . I could feel it coming. He banged the table and shouted. Billy had no right going off like that, he said, when there was so much to be put right at Granny May’s. Billy told him he’d do what he pleased, when he pleased and he wasn’t anyone’s slave. Then he got up from the table and ran out, slamming the door behind him. Mother went after him. Poor Mother, always the peacemaker.

Father and Granny May had a good long talk about ‘young folk today’, and how they don’t know how lucky they are these days and how they don’t know what hard work is all about. They’re still at it downstairs. I went in to see Billy just a few minutes ago. He’s been crying, I can tell. He says he doesn’t want to talk. He’s thinking, he says. That makes a change, I suppose.