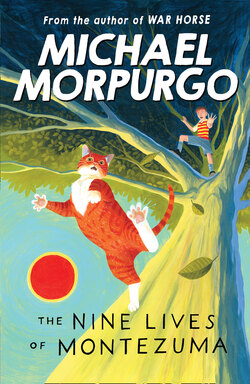

Читать книгу The Nine Lives of Montezuma - Michael Morpurgo - Страница 8

THE SECOND LIFE

ОглавлениеTHERE ARE PLACES ON A FARM WHERE NO one ever goes and it was to one of these that the she-cat carried her last surviving kitten. There was an old cob granary in one corner of the farmyard, so old and battered that it appeared almost to grow out of the stones of the yard. The only hint that it might have been man-made was the decaying corrugated iron roof that had replaced the thatch some years before. The building was used now to house the yearling cattle in winter, but the attic room above had been disused as long as anyone could remember. The floor-boards were rotten and loose, and the joists they rested on would no longer stand the weight of a man. Here a cat could live undisturbed, and here the she-cat came with her kitten to live.

Times were busy on the farm. The spring was late in coming and when the weather finally turned dry the ploughing had to take priority if the barley was to be tilled in time. At weekends the boy was left to manage most of the farm work on his own while his father rode out every morning, the plough hitched to the tractor, his lunch in his bag; and he came home only when the light failed in the evening. The boy worked well on his own, he had been well tutored by his father and had already acquired the farmer’s knack of working at a regular, unhurried pace, of moving amongst the stock with a calm confidence so that the animals barely seemed to notice he was there.

It was a warm misty morning in early April when he opened the gate and drove the yearlings out to grass for the first time in their lives. He looked on as they stepped gingerly in the softness of the grass, standing huddled together in the gateway. None of them seemed to want to take the step out onto the strange green ocean of the meadow. Then first one and then another sensed their new freedom, tossed their heads and ran out kicking up their legs in delight and leaping like lambs. The boy leant on the gate and enjoyed it, before turning back to the granary, to the task of cleaning out the bed of dung that had built up over the winter. He did not relish it.

He had filled the spreader for the first time and was sitting on the cold stone water trough resting, when he heard something moving on the ceiling above him. He stood up to listen again. There was no sound at first and then he heard a faint rustle and squeaking. ‘Rats,’ he thought and picked up the scoop to begin again. Until this moment the boy had not given another thought to the ginger kitten he had found some weeks before in the big barn, but as he shovelled away under the hay racks it came to him that the squeaking he had heard was perhaps more that of a kitten than a rat.

He climbed the granite steps that led up the side of the granary to the attic door. It was dark inside, the only window being covered with a sack. He knew the floor was dangerous and went down on all fours testing the soundness of each board as he crawled round the wall towards the window. As he reached up and pulled away the sack, he heard the sound again, louder this time and more urgent. He peered across the small room and called out in that language that people seem to think cats understand better. ‘Puss, puss, puss, kitty, kitty, kitty. Where are you, kitty?’ There was no response and he could see nothing, so he began to feel his way forward across the middle of the floor. He felt the joists spring under him and there was an ominous cracking as the wood adjusted to his weight. He stopped, waiting for the floor to be still again, and then he inched his way forward. He found the kitten lying behind a pile of disintegrating corn sacks. There was no resistance when he picked him up, the kitten opened his mouth to voice his objection but was too feeble now to utter any sound. He lay limp in the boy’s hands.

He could not be sure it was the same kitten until he had made the hazardous journey around the walls and back to the door. Once outside in the light it was clear that this was indeed the kitten he remembered, the ginger tom with a white patch on his throat that extended from the chin to his chest. The kitten had grown. Whereas before there had been no perceptible neck, his head seemed now to have distanced itself from the body; but the body itself was emaciated and wasted. Through the cold fur the boy could feel only the sharpness of bones. As if awakened by the light the kitten tensed himself and made to escape, his claws sinking into the boy’s wrist; but there was no stamina in the effort. ‘There’s life in you yet then, old son,’ said the boy as he cradled the kitten carefully in his hands and made his way back across the yard towards the house.

‘Best treat him like an orphan lamb,’ said his mother. ‘He’s half dead with cold and by the looks of him near starved to death. That Kitty has deserted him. I don’t know how she can do it. She’ll fight for her young, protect them, raise them and leave them half-weaned.’ She bent down and opened the bottom oven door of the stove. This was where they warmed the premature lambs born out in the cold of night and brought them back to life. ‘Best let it cool down a bit,’ she said.

‘How long do you think he’s been without food, Mum?’

‘Nothing of him, is there? Days I shouldn’t wonder. I doubt he’ll live, not now. Better your father should have drowned him along with those others – must be from the same litter.’

The boy folded a towel in the bottom of the oven and then knelt to lay the kitten inside. The eyes were closed now. He was breathing slowly but this was the only sign of life.

‘Shouldn’t we try to feed him?’ the boy said, adjusting the towel around the kitten. ‘Shouldn’t we try something?’

‘Not just yet. Warmth is what he needs first and the food comes after when he has the strength to take it.’

‘What will Dad say when he finds a cat in the oven?’ said the boy, dreading the moment. He peered back into the depths of the oven. ‘He’s still not moving, Mum. D’you think he’ll make it?’

‘Lap of the gods,’ said his mother. ‘Let him warm up here for a few minutes and then we’ll try a bottle. We’ll know then right enough.’

It took only a short time to wash out a bottle and teat, to water down some cow’s milk; but it became obvious before they started that the teat was going to be too big for the kitten, so the boy went in frantic search of an eye dropper and found one finally upstairs on the bathroom shelf.

His mother held the kitten on her lap as she sat by the stove, and kneeling down the boy prised open the kitten’s mouth and let the milk dribble in slowly. The eyes flickered and opened, and then he struggled pulling his mouth away. All the remaining strength in his feeble body seemed to be concentrated in a huge effort to keep his jaws tight shut. But some of the warm milk had dribbled through the fur and seeped into his mouth. He swallowed because he had to swallow, and he liked what he tasted. He opened his mouth for more, and the boy took his chance and squeezed the dropper. The kitten coughed and spluttered as the milk rolled down his throat, but his tongue had found the end of the dropper and discovered that this was the source. He sucked and found that the milk came through. Four droppers he sucked dry before he lay back, replete. ‘Back in the oven, Monty,’ said the boy. ‘I think you’ve had enough.’

‘Monty? Why Monty?’ his mother asked.

‘Montezuma, the Aztec king. He was a survivor, a great fighter. I read about him last term in history.’

‘But he was killed, wasn’t he? By the Spanish. Didn’t they strangle him in the end?’

‘Yes,’ said the boy, putting the kitten in the oven. ‘Yes, they killed him, but it took them a long time. And we all have to die in the end, don’t we, cats and kings, it doesn’t make any difference. But it’ll take more than a case of starvation to kill Monty off. I know this cat, Mum.’

‘You like him, don’t you?’ His mother was surprised. The boy had never shown that much affection for animals, a farmer’s interest certainly but little involvement; and fourteen year old boys don’t usually fall for kittens.

‘He’s special, Mum,’ the boy said. ‘He’s not just an ordinary kitten. He’d be dead if he was, wouldn’t he? What would you say if I wanted to keep him?’

His mother shook her head. ‘You know your Father’s views. Animals stay out on the farm. We live in here, they live out there. He won’t even have the dog inside the house and Sam is useful, part of the farm equipment you might say. If he won’t agree to Sam, he’s not likely to agree to a cat.’

‘But Monty deserves it,’ the boy pleaded.

‘You tell your father that, but don’t expect any help from me. I’m neutral in any arguments between you two.’ She put her arm around him and said warmly, ‘But just between you and me, I hope you win. There is something about that cat, like you say.’

Mother and son were just preparing another dropper when they heard the tractor rumble into the yard outside. The whistling came nearer the door and they heard stamping boots on the step outside. The boy looked down at the open oven and there was the kitten peering out, ears pricked, eyes bright. The boy touched wood, crossed his fingers and said a quick prayer. Then the door opened.

‘Finished both fields on the other side of the brook, headlands as well. But ’tis still divilish wet out there.’ His father sounded content and satisfied with his day, and the boy decided that this was the time to make his case.

‘Dad,’ he said, wondering how best to begin. ‘Dad I found a kitten in the old granary this afternoon.’

‘Did you clear it out like I said?’ His father bent over the sink to scrub his hands.

‘Yes, Dad. It’s all done.’

‘And the milking? Are you sure that Iris hasn’t got mastitis? She felt hard enough to me last night, in the two front quarters. You sure she’s all right?’

‘Quite sure, Dad.’

‘And what about Emma? She looked as if she might calve early. Any sign?’

‘No, Dad. Dad, about the kitten ...’

‘Is there a cup of tea in the pot?’ His father wiped his hands and turned around to face the oven. ‘Gad, what the divil’s that in the oven?’ He stooped for a closer look, hands on his knees. ‘It’s a perishing kitten. What the divil’s a perishing kitten doing in here? Will someone tell me what the divil he’s doing in that oven?’

‘Dad, I’ve been trying to tell you. That’s the kitten I found in the granary. He’s been deserted by that Kitty.’

‘But I drowned her last lot.’

‘Not all of them, Dad. You must have missed this one, and I found him all starved and nearly dead. Mum and me, we’ve been feeding him up; and Dad, I wanted to ask you if . . .’

‘Gad,’ said his father, and he reached in the oven and pulled the kitten out, holding him up by the scruff of the neck.

‘Too old to drown now, dear,’ said the boy’s mother. ‘What’ll we do with him?’

‘What’ll we do with him? You can’t just throw him out, wouldn’t be right. You’ll have to keep him, won’t you? Just take care you keep him out of the sitting room, that’s all.’ He looked the kitten straight in the face, nose to nose. ‘Never in the sitting room, you hear me?’ And he handed the kitten to the boy.

‘All yours, Matthew,’ he said. ‘What’ll you call him?’

‘Monty,’ said Matthew. ‘Short for Montezuma.’

‘Divilish silly name, but there you are, Matthew’s not much better. Monty meet Matthew, Matthew meet Monty.’

‘D’you mean I can keep him here, Dad? He can stay?’

‘Nothing else to be done, is there? Now what were you going to ask me, Matthew? You said there was something . . .’

‘Nothing, Dad, it was nothing. Can’t have been important. I’ve forgotten.’

‘Where’s my tea then? Gad, can’t a man have a cup of tea when he gets back home at night. What are you both staring at?’

And so Montezuma came to live in the farm-house. After a few days he was moved away from the oven and into a box on the far side of the kitchen under the ironing board. But that was a long way from the stove, and he very soon found a corner of the stove by the wall where he could sleep warm and undisturbed whilst he grew slowly into adolescence.