Читать книгу My Friend Walter - Michael Morpurgo - Страница 8

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеBEFORE I TELL YOU ABOUT THE POSTCARD I HAD better tell you something about me. My name is Elizabeth Throckmorton and I’ll be eleven on my next birthday. Aunty Ellie (you’ll meet her later) calls me her ‘china doll’ on account of my pale skin and straight black hair. I’m small for my age, so people at school think I’m feeble and fragile which I’m not. I don’t talk much, so they think I’m unfriendly which I’m not. I just get on better with myself than anyone else, that’s all.

Around me at home there’s my family. First there’s Father, who’s a farmer. Father treats me like a boy. I think he always wanted me to be a boy, really. Then there’s Mother, who’s always busy. If she’s not out on the farm she’s scurrying about the house with a broom or a pile of dirty washing. She never stops. She doesn’t seem to have time to talk to me much these days, not since Little Jim was born; but we understand each other – always have done. Not like my big brother Will. We haven’t got much in common, Will and me. When he’s not shooting or fishing, he’s down in the cellar making horrible smells in the chemistry laboratory he’s set up down there. I’d like to like him more – I know I ought to.

Then there’s Little Jim. Little Jim was born about eight months ago. He always needs feeding or changing or picking up or mopping up. I spend a lot of time looking after Little Jim, but he doesn’t seem to appreciate it. He loves to pull my hair out by the roots or to tear my ears off whenever he can. He never does that to Gran. Gran has been living with us in the house for as long as I can remember. She’s nearly eighty now. I know she means well, but she does go on a bit sometimes.

I suppose you could say that it was an ordinary sort of a morning in our house the day the postcard came. The toast burnt and Father shouted and spluttered with his mouth full of cornflakes. I was giving Little Jim his breakfast. Mother was trying to rescue the toast and to see to Gran’s boiled egg, all at the same time. Will was in the bathroom. He’s always down last. Humph is our black and white sheepdog with a killer instinct for letters and postcards, and it was Humph that heard the postman first. He rose with a terrible growl from his catching position under Little Jim’s high chair and fairly flew out of the kitchen door. He returned seconds later, his tail high with triumph, a postcard in his mouth, wet and punctured as usual. Mother told him to drop it. Humph looked at her blankly, pretending not to understand. He had learned that if you hold out long enough you get one of Little Jim’s rusks in exchange for the post. And sure enough he got one this morning.

‘Well, I’m blowed,’ Father said, picking the postcard off the floor. ‘What do you make of this, then?’

‘Of what, dear?’ said Mother, wiping her hands on her apron and coming to look over his shoulder.

‘Can’t hardly make it out,’ said Father, peering at it closely. ‘’S funny writing, don’t you think? Anyway, seems we’re all invited to some sort of family reunion. Never heard of such a thing, have you?’

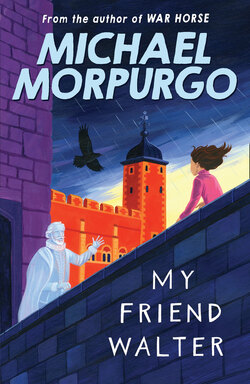

‘What’s it say?’ I asked, looking at the picture on the back of the postcard. It was of the Tower of London with a Beefeater standing outside looking very serious.

‘It says: “To the family Throckmorton” – that means you too, Jimmy.’ Little Jim waved his arms up and down like a tin drummer boy and then rubbed his soggy rusk in his ear. ‘It says: “You are invited to attend a grand reunion of our family to be held at the Tower Hotel, London, on the fourteenth of July at noon. Have your name writ upon you so we may know one another”.’

‘Very mysterious,’ said Mother. ‘I wonder who sent it. Can’t spell, whoever it is. Should be “written” not “writ”. And it’s not signed at all. Just look at the writing, Bess. Worse than yours.’ And she turned the card round to show me. The handwriting was all squeezed up and tall. I could hardly read a word of it.

‘Rum business if you ask me,’ said Father. ‘Could be a hoax for all we know.’

‘Nonsense,’ Mother said. ‘People have family reunions all the time. I think it’s a lovely idea. I’d love to go, but the fourteenth – I think something’s happening on the fourteenth.’ And she went over to look at the calendar by the phone. ‘Oh dear, I thought so. We can’t go, not on the fourteenth. You’ve got to see the accountant in the afternoon, dear. Little Jim’s got his diphtheria jab in the morning at the doctor’s. And you were coming with us, Gran, for your check-up, remember? What a pity.’ Gran was about to protest. ‘It would be too much for you anyway, Gran. You know what the doctor said about overdoing it. And Will’s still away at camp with the school. Where did they say they’re having it?’

‘The Tower Hotel, it says here,’ said Father. ‘Up in London. Somewhere near the Tower of London, I suppose.’

‘That’s where they cut off all those heads,’ said my brother Will, doing up his trousers as he came in the door. He growled at Humph as usual, who growled back as usual. ‘I’ve been there,’ said Will. ‘I’ve seen the very place where they cut off their heads. I’ve seen the axe. Sharp as a razor it was. Mind you, one of them Beefeaters said it sometimes needed three or four swipes if your neck was a bit thick.’

‘Will!’ said Mother. ‘That’s quite enough. Now sit down and eat your breakfast.’ She turned to me. ‘But you can go, Bessy. If we could find someone to take you, you could go.’ I shook my head. I didn’t like parties at all and there’d be lots of strange people. ‘Bound to be lots of other children there,’ Mother went on. ‘You’d like to meet your cousins, wouldn’t you? I wonder if Aunty Ellie got an invitation. She’d take you, I know she would.’

The telephone rang, and Mother was right beside it. It was Aunty Ellie; and yes, she’d had an invitation. No, hers wasn’t signed either, and yes, she’d take along anyone who wanted to go. Everyone told me I should go. ‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained,’ said Gran. ‘Be interesting,’ said Mother. So I went.

As it turned out the party wasn’t a bit interesting, not to start with, anyway. Once at the hotel, I trailed around after Aunty Ellie through a sea of relations that I had never met who peered at the name on my label – as the invitation had said, everyone wore labels so we could find out who we all were – and they asked me where I lived and where the rest of my family was and where I went to school and what hobbies I had. I would tell them I liked reading books and painting pictures and following butterflies – for some reason that seemed to make them laugh. I can’t think why. I ate two flakey sausage rolls which were delicious, some apple tart which was not, and drank glasses of orange juice. I glared back at a few distant cousins who glared at me, and then because my legs were tired and because I couldn’t really cope with my third sausage roll and a sticky bun and an orange juice all at the same time, I looked for somewhere to sit down.

I left Aunty Ellie chatting to an aged great uncle who wore striped braces to hold his trousers up over his huge stomach, and went to sit by myself on an empty sofa. Everyone seemed to have a lot to say to everyone and there must have been some good jokes (although I didn’t hear any) because they were all laughing a lot and loudly. I had finished my sausage roll and was wondering which end of my sticky bun to bite into when I noticed there was someone else sitting beside me. It startled me because I’d thought until that moment that I was alone.

Sitting on the far end of the sofa was an old man with a silver-topped cane. He was swathed in a long black cloak which covered him from head to toe. He was smoking a pipe, a long elegant silver pipe; and he was leaning forward over the top of his cane studying my label and then my face. ‘So you are Elizabeth Throckmorton?’

I nodded.

‘I have been searching for you.’ He looked at me more closely and smiled and shook his head. ‘Long ago I knew someone of the same name,’ he said. ‘She was older, I grant you, yet the likeness is unquestionable. You have her eyes, you have her face.’ His voice was strangely reedy and high-pitched, and he spoke with a burr much as we do in Devon. He seemed to be waiting for me to say something, but it was hard to know what to say, and so I said nothing. The old man began to chuckle as he looked around the room. ‘If Sir Walter himself could be here,’ he said, ‘I wonder indeed what he would think of his family.’

‘Sir Walter?’

‘Sir Walter Raleigh!’ he said rather sternly. ‘You have heard of him I trust?’

‘Yes, I think so,’ I said. ‘Wasn’t he the one that laid his cloak in a puddle so Queen Elizabeth could walk across without getting her feet wet?’

The old man looked at me long and hard and then sat back on the sofa and shook his head sadly. ‘Is that all you know about Sir Walter Raleigh? Well, you should know more. Do you not know that he is an ancestor of yours?’

‘Of mine?’

‘A distant relative I grant you, but everyone in this room has the blood of Walter Raleigh running in their veins, albeit thinly.’ He drew on his pipe and sighed as he looked around him. ‘It is hard to believe it, but it is so.’ He turned to me again. ‘He lived close by for some time, you know.’

‘Close by?’ I said.

‘In the Tower of London. If ever a man served his country well it was Walter Raleigh – and how did they repay him? They locked him up and cut off his head.’

‘Cut off his head? But why?’

‘That is indeed a long story and a hard one for me to tell.’ He leaned forward again and spoke gently. ‘But since you have some connection with him by blood, perhaps you should go and see where he lived all those years ago. Thirteen years he was there. Thirteen long, cold years in the Bloody Tower. You should go there child. You should see it.’ He gripped my arm so tightly that it frightened me, and looked at me earnestly. ‘He is part of your history. He is part of you. Will you go?’

‘I’ll try,’ I said, and he seemed happy with that.

He looked past me. ‘I long for something to drink, child; but there is a crush of people about the table.’

‘I’ll fetch it,’ I said. ‘Tea?’

He smiled at me. ‘Wine,’ he replied. ‘Red wine. I drink nothing else. I shall be here or hereabouts when you return.’ When he stood up he was a lot taller than I expected. I looked up into his face. His beard was white and pointed, and he seemed for a moment unsteady on his feet. ‘Back in a minute,’ I said.

I suppose I was gone a little longer than that because there was a queue for the wine, but when I came back he was nowhere to be seen. I asked after him everywhere but no one seemed to have noticed a tall old man in a black cloak carrying a silver-topped cane. I thought I had found him once and tugged at a black-cloaked figure talking to Aunty Ellie, but he turned out to be a vicar in his cape and so I offered him the wine anyway to cover my embarrassment. Aunty Ellie was delighted at my politeness. She introduced me as her little niece, her ‘little china doll’; and I was once more yoked to her skirts and paraded around amongst my inquisitive relatives. But I remember little enough of the party after that for all I could think of was the tall old man who had appeared and then disappeared, who had insisted that I visit the Tower where Walter Raleigh had been locked up all those years. The more I thought about it, the more I wanted to go; but I wondered how on earth I was going to persuade Aunty Ellie to take me.

In the end, though, it was Aunty Ellie herself who suggested it. She had met up with a long-lost cousin of hers whom she had not seen since she was a child and I suppose they wanted something to keep me happy, or quiet, whilst they reminisced about the childhood summer holidays they had spent together by the sea at somewhere called Whitstable. We could either go on a trip up the river or to the Tower, Aunty Ellie said. Which did I want? ‘The Tower,’ I said. And so I found myself that afternoon inside the Tower of London walking past red-coated, bearskinned guards whose eyes wouldn’t even move when I looked up into them, past Beefeaters who smiled down at me and curled their abundant moustaches as if they were Father Christmases.

As we stood in the queue waiting to see the Crown Jewels, I tried to ask Aunty Ellie about Walter Raleigh. After all, if he was related to me he was related to her too. She told me not to interrupt and finished telling her blue-haired cousin, Miss Soper I was to call her, all about her life as a midwife, about how she had looked after almost all the new-born babies born in Devon for over thirty years and how so many of them were named after her. ‘Now dear,’ she said, turning to me at last, ‘what was it?’

‘Someone at the party told me we were related to Walter Raleigh.’ Aunty Ellie opened her mouth to speak, but Miss Soper got there first.

‘Indeed, we are, dear,’ said Miss Soper. ‘But thankfully only distantly, and on his wife’s side. He was a terrible rogue, that one. He was imprisoned here, you know.’

‘I know,’ I said.

‘And he was a traitor,’ said Miss Soper. ‘That’s why he had his head chopped off. We are much more proud of our Sir Francis Drake connection, aren’t we Ellie? The Sopers are related much more directly to the Drakes than the Raleighs. Now there was a man if there ever was one. Francis Drake.’ She took a deep breath. ‘Drake is in his hammock and a thousand miles away . . .’ and Miss Soper began to recite a poem in such a loud and impassioned way that the whole queue gathered around her to listen, and then clapped when she had finished. ‘I think, Ellie,’ she said, giggling with embarrassment, ‘I think I drank a teeny weeny bit too much wine at the party.’

‘I think so too,’ said Aunty Ellie, ‘But what does it matter? Oh, it’s so good to see you again, Winnie, after all this time. You haven’t changed a bit.’ And they hugged each other for the umpteenth time and I began to wish I was with someone else.

We saw the Crown Jewels and ooohed and aaahed with the others as we filed past all too quickly. There wasn’t time to stop and stare. There were always more people behind, pressing us on, and Beefeaters telling us to move along smartly. The Crown Jewels were splendid and regal enough but they looked just like the pictures I had seen of them, no better. I was impatient to get to the Bloody Tower to see where Walter Raleigh had been imprisoned, and it was already getting late. When we came out of the Crown Jewels Aunty Ellie said there’d only be time for a short visit to the Bloody Tower.

So I found myself at last inside the room where Walter Raleigh had spent thirteen years of his life. There wasn’t much to see really, just a four-poster bed, a chest and a tiny window beyond.

I walked up and down Raleigh’s Walk, a sort of rampart that overlooks the River Thames, and I wondered again about the old man no one else had seen at the party.

Storm clouds had gathered grey over the river and brought the evening on early. The river flowed black beyond the trees and people hurried past to be under cover before the rain came. I was alone and I was suddenly cold. Aunty Ellie and Miss Soper had gone on without me. They would wait for me outside by Tower Green, they said. They had found the Bloody Tower grim and damp, not good for her rheumatism, Aunty Ellie said. ‘Don’t you be too long,’ she’d told me. ‘We’ve got to get back.’

I was wondering why Walter Raleigh hadn’t just made a rope out of his sheets and let himself down over the wall. It’s what I would have done. I leaned over the parapet. ‘Too far to jump,’ said a voice from behind me. A tall figure was walking towards me, his black cloak whipping about him in the wind. He was limping, I noticed, and carried a silver-topped cane. ‘So,’ he said. ‘So you came. Allow me to present myself.’ He bowed low, sweeping his cloak across his legs. ‘I am, or I was, Sir Walter Raleigh. I am your humble servant, cousin Bess.’