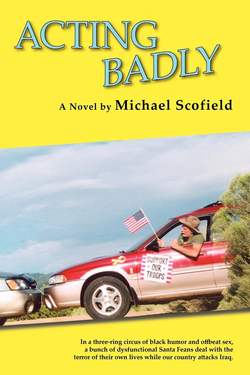

Читать книгу Acting Badly - Michael Scofield - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ACTIVIST

ОглавлениеPULLING HIS RED KNIT CAP OVER HIS EARS, MANNY KNELT in the mid-March chill beside the left rear tire of Ron’s new white 2003 Escalade. He winced as the gravel bit his skin. Lying in bed waiting, he’d heard Ron and Lila drive in; the tire’s wall was still warm. As the light behind the glass blocks in their upstairs bathroom dimmed, a gibbous moon lit the American-flag decal darkening the rear window of the gleaming sixteen-footer.

Manny stiffened as a gust rattled the string of dried red chiles hanging from the front porch. The only other sound came from below his and Joyce’s and the Kirkpatricks’ town houses, shouts from the softball game on Baca Field. Proud he’d slipped downstairs without breaking Joyce’s snoring, Manny swelled his lungs with a menthol-like whiff of the rabbitbrush that lined the Kirkpatricks’ drive, and bent close to the tire.

Belching, he unscrewed the ridged cap of the air valve and laid it aside. From a pocket of the sheepskin coat over his robe and sweats, he pulled a long finishing nail and leaned to jam its head into the valve. He pinched his nostrils against the stale hiss, watching the Escalade’s stack of brake and backup lights tilt and begin to sink.

The junipers and prickly pears fronting a town house on the dirt road’s other side suddenly brightened from charcoal to lime green. Starting from the bottom of Plaza Hill, where the private neighborhood began, a crunching grew louder. It’s nine-thirty, go to bed, he thought, and rolled to his side, scraping his left cheek.

Like a rattlesnake he wriggled to the front end of the listing Escalade. He tucked his lankness below the grille’s five blades of chrome, which sparkled from the lamp that lit the Kirkpatricks’ steps. He patted his cheek; blood made his fingertips sticky. Had he ripped his coat, he wondered?

Headlights jerked left and right as the Range Rover with its three-tiered, wraparound brush bar swerved across his view. Maxine Morgan’s—he could see “Morgan Realty” on the door, an albino bobcat springing along the letters’ tops.

The behemoth skidded and paused. Pressing his stomach to the gravel, Manny listened to the engine idling. He peeked past Ron’s front tire as acid rose to his throat. In the moonlight the driver’s window lowered with a hum and a fist flung a tiny bundle rolled up like a newspaper. It plopped near him. White smoke puffed from the tailpipe, another hum, and the SUV wove down the other side of the hill, rear lights waving.

What was she doing up here tonight driving drunk?

The pounding behind his eyes told Manny that he’d stopped breathing. He pursed his lips and blew out air, then eased out the gas that had built up in his colon so not to make a noise. Standing, he threw his elbows behind him to unkink his bony shoulders.

He stared at the white handkerchief or rag rubber-banded to hold some sort of cylinder from which wafted a stench of pepper sauce. Pinching his nose to keep from sneezing, he kicked the bundle toward the rabbitbrush, padded back to the Escalade’s rear tire, and knelt again to finish his task.

Following the new hiss, the corner of the white bumper settled a few inches above the drive, curling back the mud flap as the trailer hitch thumped the gravel.

He screwed the valve cap tight and closed his eyes. Still on his knees, he arched backward and, shivering, steepled his fingers. To the first dirty-footed burkha-wrapped Iraqi clutching her infant, blasted to shreds by an American Tomahawk tagged for Saddam Hussein, I dedicate this hamstrung White Diamond Escalade, he whispered to himself.

Rising, he tasted the sweet salt of blood on his fingertips, then pressed them to the Escalade’s fender. Blood sacrifice, fat Ron. He watched his breath pulse out.

With the toe of his moccasin he nudged the cloth-wrapped bundle out of the bushes onto the gravel, kicked it, and kept kicking until it rested beside the flat tire. He hurried around the piñon-strewn embankment that separated his and Joyce’s town house from the Kirkpatricks’.

Except for the red-eyed surge protectors he’d bought to save his stereo equipment from lightning zaps, no light showed in the hallway. He climbed the stairs’ thick blue pile. Crinkling his nose against the hot-pepper scent rising from his moccasin, he eased open the door he’d shut twenty minutes before, and peered at the bulge of Joyce, curled under the electric blanket in the far corner. Off the master bath he dumped sheepskin, robe, and red knit cap on the walk-in closet’s floor.

Above the bed the moon lit two of Joyce’s anti-war poems just accepted by Cholla Review; he had framed and decorated the typescripts with cholla spines and sunflower petals. He stood on his side of the bed and lifted to his nose his left moccasin, wondering whether to scrub it. She mumbled, “Hey, bud, where’ve you been?”

A foot shorter than he, Joyce sat up in the moonlight, and pulled the blanket around the top of her flannel nightgown. “What’s that stink?”

Sighing, he sank to the mattress and told her; his gut hurt as though she were twisting a loop of his intestines with pliers.

“Knock it off, Manny! It’s not your business what real estate games Maxine Morgan wants to play. Who do you think you are letting air from that tire, Mahatma Gandhi?” She jerked the electric blanket tighter around her shoulders. “I don’t like what’s happening since we moved to Santa Fe, bud.”

“Meaning?” Pressing his lips against a belch, he raked the tips of his fingers through his short hair.

“Your games with women. Two years ago, after we signed the deal for this place. The lunch that Maxine Morgan and Ron bought us at the Great Books Cookhouse. I should have stayed alert.”

“You’re saying what?”

“How you spooned blackberry flan from her dish.”

“What the hell, Boodie.” It was the name he’d given her after she’d startled him, leaping around the corner like a blonde cricket at Sun Microsystems in Silicon Valley, where she’d edited Sun’s employee newsletter.

The sharp sweetness of blackberries filled his mouth; again he saw Maxine widening those violet-smeared eyes at him.

“And telling Ron Kirkpatrick’s wife at the homeowners’ meeting how you love blue flax. You mean loved her unbuttoned blouse. She’s an easy ten years older than us, Manny.”

Tenderness swamped his insides. He loped around the foot of the bed, pulling Joyce’s mop of blonde hair against his stomach. He felt her shoulders sag, and for the moment didn’t care that she’d decided to let the hair of her armpits and legs grow.

“Boodie, it’s your breasts I love, especially when you rub them on my cock and face.”

“Your flirting scares me. So does wanting us to quit drafting marketing newsletters for Sun and Hewlett-Packard and Cisco. What are we supposed to do, live on the settlement from my divorce?”

“Chuck’s diversified me into green stocks and municipals. I’m in good hands.”

“You’re as naïve as he is. He may be fine as your CPA, but with investments Chuck Ridley’s a fool.” She freed her small head from his grasp and pushed him away. He staggered to the wall—its rough plaster pricked his back. “Stocks are tanking, it’s the deepest bear market in thirty years. We’ll have to sell this place.”

She clutched the sheet to wipe her eyes, then faced him. “We’re planning marriage and a baby before I’m forty-five, aren’t we? I should be ovulating midweek. Moving here makes me nervous. Okay, we got desperate. Christ, in every Bay Area garage some geek is lying on a cot scheming how to infect our lives with nanoelectronics. And I know your therapist suggested you go—don’t stand so far away from me.”

He crossed the four feet between them, plopped on the bed, and threw his sweatshirted arm around her waist. “We’ll cut our spending, Boodie. I won’t need to fly to San Jose for editorial meetings anymore. No hotel bills.”

“Naïve. Hey, I’m tired, too, of grinding out newsletters. And I’m sick of writing poetry. What’s the point? I told Allie at lunch today I want a life of muesli to prepare for the baby. But we can’t afford muesli. Meanwhile, you stir up trouble next door and fantasize I don’t know what about women.”

“Enough, Boodie.” He swallowed against another belch. His gut was crimping and, though clothed in sweats, he’d begun to shiver. The furnace must have quit for the night. “I gotta get my robe.”

He was on his way to the closet when he heard her cry out.

“What’s wrong?”

“It’s that scrabbling noise again!”

“Switch on the lamp in your basket.” He yanked his red-plaid robe off the closet floor. Now that a couple of journals wanted to publish her jeremiads, she planned to stop writing? With the Cheney-Rumsfeld-Wolfowitz axis of evil turning Christian fundamentalism into a world crusade, she and he needed to march, wave signs, and register Democrats to boot out the Bush cabinet next year. She needed to publish all the antiwar poems she could.

“Hear it?” She pointed above the water stain that darkened the wall between her poems. In the brown wool socks she slept in, she bounded from the bed and stood beside the night table, where her book of Sanskrit meditations lay.

“Seems the beast can’t decide which poem to settle down over.”

She mussed her blonde hair, laughing.

What a doll—why her patent-lawyer husband left her for a legal aide with two sons he couldn’t imagine. Except that Joyce couldn’t get pregnant by him. “If Stu decides not to march Sunday, maybe he’ll come help find where the beast’s wriggling through the tarpaper. I wonder what eye patch he’ll wear this time?”

“Who knows—how can we sleep with that noise?”

“We can’t. I want to show you something.” He moved to the bookcase near the stairs, reached below her volumes on nutrition to where he kept his jazz CDs, and yanked out a three-ring binder. He padded to the tattered armchair that had been her father’s near the sliding glass door that led to the lower roof, and flicked on the floor lamp.

“Come here.” He patted the red wool plaid covering his thigh.

“I don’t like this alpha-male habit you’ve developed since leaving the Valley.”

“What habit?”

“Giving me orders.”

“Sorry; you’re right.”

Her buttocks warmed his lap. “What happened to your cheek?” she asked, touching the rawness with two fingers.

“Hey, don’t! I scraped it trying to scramble out of Maxine’s high beams. Forget that. See this?” He flattened his hand against the binder’s cover. “Chuck downloaded it: Rebuilding America’s Defenses. Published in two thousand by a think tank called The Project for the New American Century. Paul Wolfowitz is a member.

“Seventy-six pages laying out why nothing is going to stop us from manhandling the Middle East. Does Bush believe Saddam has weapons of mass destruction? He knows Scott Ritter’s UN team got rid of them in the mid-nineties. Rebuilding America’s Defenses says we’re going to force peace through economic globalization, backed by expanding military beachheads in the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Use designer weapons like nuclear bunker busters and mini bombs.”

“Christ, Manny!”

“The Bush bunch wants to pummel the Axis of Evil, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan into cobbling up American-style democracies. All it takes is persuading two billion followers of Islam to change their faith. Is that crazy? You and I have to do something.”

“Like letting air from Ron’s tire?”

“We ought to let air from the tires of all the American-flag gas-guzzlers in Santa Fe, cop us a slot on TV.”

She jumped off his lap, clamping the light-blue flannel to her chest. “Who’s crazy here? We left your stomach cramps from too much cranial mania back in Palo Alto. Didn’t we? Count me out of your activist dreams, Manny.”

He stiffened and shifted his eyes toward the glass door.

“What in the world?” Joyce whispered.

They listened to a loud snap, followed by a rattling and banging—rocks careening down the hill?

Throwing the binder to the carpet and tightening his sash, Manny heaved open the sliding glass door and closed it behind him. The din had stopped. Cold bit his cheeks and neck. Baca Field’s floodlights had darkened. He stared at the moon, at Santa Fe’s lights aproned below, and the glow rising over the Sandias from Albuquerque. Few SUVs or workers’ trucks raced this late along Bishop’s Lodge Road.

Manny rubbed his belly to quell its gurgling. Oh God, he begged, give me something meaningful to do. That little silver ring high up in Alexis’s ear; me hoping she’s bi. Why am I flirting again? Didn’t losing my savings to three abortions cure me before I met Joyce? I have my life partner, don’t I? “Praying to a God I don’t believe cares—I must feel desperate,” he muttered.

Shivering, he pulled open the slider. “Nothing to see except lights.”

“It sounded worse than the racket the hot tub makes.” She clicked off the floor lamp, then moved toward the bed and twisted the knob of her table lamp.

“That hot tub’s a pain,” Manny said in the moonlit dark. “Maintenance and chemicals run five hundred bucks a year and it leaks. Stu thinks the grinding means a blockage. Let’s dump the whole system, Boodie—it’s a capitalistic frill. No more stains, no more rats.”

Kicking off his moccasins, he tossed his robe on the seat of the ladderback chair in the corner. He peeled off his sweats and Jockey shorts, stretched under the blanket, and threw a forearm over his eyes. “Everything’s going to be fine,” he murmured, worrying that tomorrow, after picking up a peace placard from Alexis at Chuck’s office, he and Joyce must grind out April’s CEO Briefing.

Joyce brought her knees up and faced him. “Hey, bud?”

“What?”

“I love our hot tub. I love to sit on the bench and soak when the plum branches above it wave. I like us to touch; I like you to touch me between my legs.”

Her palm slid across his pelvis and settled on his testicles. Her thumb pressed his penis.

“I like it when we wrap each other in towels and come dripping up here to make love, Manny. Don’t you? But we can’t do it when you’re overwrought and can’t get hard.”

“Tomorrow, Boodie. It’s ten o’clock, I’m tired.”

She retrieved her hand and flipped to her other side. He snuggled in close, genitals and belly pressing her buttocks. He hooked his arm around her waist to cup a breast, but her hair tickled his nose and he pulled away. He winced at the cramp of intestinal gas building—what a joke that he could leave stomach problems in California.