Читать книгу Truth and Revolution - Michael Staudenmaier - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One: 1969, The Revolution That Didn’t Happen

ОглавлениеNineteen sixty-nine was a difficult year for North American revolutionaries. Black radicals, in the Black Panther Party and other groups, were under direct attack by the FBI and local police across the United States. Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the flagship organization of the white new left, imploded at its annual convention in Chicago. The war in Vietnam was intensifying, as Richard Nixon reinforced and expanded the imperialist foreign policy that Lyndon Johnson had previously administered. Everywhere the initiatives championed by the new left were on the defensive, as capital and the state dug in their heels to defend the status quo.

At the same time, 1969 was also a year of great optimism for North American revolutionaries. Enormous numbers of young people across the country embraced the term “revolution.” In the eyes of many, the wheat was being separated from the chaff, as the gulf between culturally oriented hippies and ideologically committed militants grew ever greater. The collapse of SDS was viewed as a symbol of the limits of student-centered radicalism, and attention turned to the growing wave of wildcat strikes in a variety of industries where workers were openly rejecting the sweetheart deals that mainstream unions had established with employers. An increasingly radical women’s movement was growing by leaps and bounds, challenging male supremacy within both mainstream society and the established left. If the bad guys were digging in for a fight, the good guys were getting more sophisticated, more determined, and more energized in their efforts to turn the world upside-down.

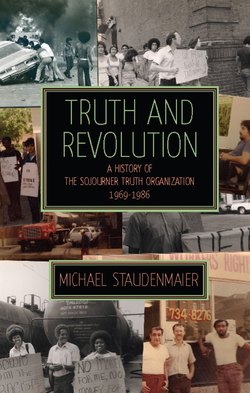

In this contradictory context, a small number of revolutionaries in Chicago spent the fall of 1969 discussing the state of the movement and the prospects for radical social change. The process culminated, sometime between Christmas and the New Year, in the founding of the Sojourner Truth Organization, a group that would spend most of the next two decades critically engaged in revolutionary struggles. In order to better understand the origins of STO, it is useful to briefly review the circumstances in which its founding members found themselves in the year leading up to the group’s inception.

* * *

The black movement was both huge and diverse in 1969, although signs were already visible of the pressures, both external and internal, that would decimate it as the seventies progressed. The civil rights movement had been torn for some time between the reformist approach of most of the major southern organizations and the increasing radicalism of the urban rebellions that began in the mid-sixties.7 By the time Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968, the organized face of the black movement included groups like the Black Panther Party (BPP), the Republic of New Afrika, and the Revolutionary Action Movement. These and other organizations advocated black power and favored a revolutionary approach to the problem of white supremacy, in contrast to the reformism of more established formations, such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and even the Congress of Racial Equality. But as the number of radical black groups proliferated, so did the tensions between them, and in some cases inside them. Some of these conflicts were the result of government repression and COINTELPRO tactics, while in other cases the FBI and local police exploited already-existing disagreements between groups to further fracture the movement.8 For a time, the problems at the organizational level were more than outweighed by the vibrant mass movement of black people everywhere against the daily experience of racism in all arenas of life. As this momentum dissipated over the succeeding decade, the difficulties plaguing the organized black left served as both cause and effect of the decline. But even before the movement as a whole was in trouble, the conflicts and the repression had a ripple effect on the rest of the left.

The Panthers, in particular, had ties to SDS and other largely white groups, so their internal tensions and the government attacks they suffered had a demoralizing effect on the section of the white movement that took inspiration from their bold rhetoric and deep commitment to social change.9 Over the course of 1969, the BPP was on the receiving end of just about every form of government repression one can think of. Activities and communications were subject to surveillance, key leaders were arrested on trumped-up charges, and the Panthers’ public commitment to armed self-defense was used as an excuse for police to conduct violent assaults on their offices and the homes of members. On April 2, the “Panther 21” were arrested in New York City and charged with conspiracy, arson, and attempted murder; although they would eventually be acquitted, their legal defense put significant strain on the BPP’s east coast operations.10 Then on December 4, the Chicago Police Department invaded the home of Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton, murdering him in his bed and also killing BPP leader Mark Clark.11 Internally, these and other attacks did nothing to diminish the growing divide between the Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver factions of the BPP, which by early in 1971 had turned into a full-blown split in the Party.12

It was impossible at the time to predict the coming decline in the black movement. In part, this was due to other developments that were much more encouraging. The most impressive of these was the emergence of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW) in Detroit during the summer of 1969.13 The League represented an alternative to the Black Panther Party, both in its organizing methods and in its constituency. Where the Panthers advocated the rhetorical flourish, the open show of firearms, and the establishment of direct service antipoverty programs, the League preferred grassroots organizing in the workplace, the use of legal defense as a form of propaganda, and the creation of alternative media institutions like publishing houses. In each case, the means chosen reflected the segment of the population targeted by the group: the BPP aimed its efforts at the black underclass, including unemployed and semicriminal elements, while the League attempted to engage sectors of the black working class, especially in the auto industry and in community colleges. These differences held enormous significance for the future members of STO, who were much more interested in the LRBW than they were in the Panthers.14

The League was always an unstable combination of organizers with different agendas and strategies, but it symbolized a convergence of the black movement with the promise of workplace rebellions like the wildcat strike at the Dodge plant in Hamtramck, Michigan in May, 1968. This strike led to the creation of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), from which came some of the founding members of the League a year later.15 Others came out of the black student movement and from a loose collection of slightly older activists in Detroit. The unique situation of Detroit as a heavily black and heavily industrialized city limited the applicability to other locales, but the example of the League was certainly inspiring to a cross-section of the white left, just at a moment when the problems facing the Panthers were becoming difficult to ignore.

The LRBW was not the only positive news from the black movement, either. The legacy of the civil rights movement as a militant, grassroots struggle with an undeniable base of support in black communities nationwide was still strong, despite King’s death and the organizational splintering described above. As early as 1967, Carl Davidson, a leading member of SDS, argued that

the black ghetto rebellions this summer fundamentally altered the political reality of white America, including the white left. The black liberation movement has replaced the civil rights and anti-poverty movements, revealing the utter bankruptcy of corporate liberalism’s cooptive programs. The events of this summer marked not only the possibility, but the beginning of the second American revolution.16

Two years later, despite all their difficulties, the Panthers remained a highly visible organization that at least initially seemed to hold up well under increasing government repression. Smart revolutionaries understood that any serious attempt to overthrow capitalism would face the harshest possible attacks from the power structure, and the black movement was perceived as the segment of the US population most prepared for these attacks and most committed to resisting them.

* * *

One result of the League’s activities, especially its commitment to self-promotion through alternative media, was that, as the sixties came to a close, increasing numbers of young leftists began to pay attention to the industrial workplace as a site of social struggles. Several factors had previously kept the new left from investigating workplace struggles. The dominance of SDS within the white new left led to an overwhelming emphasis on student issues and campus-based struggles. Even when they turned their attentions outward, most student radicals focused their efforts on community organizing and antipoverty campaigns, rather than labor issues. Many SDS members felt nothing but disdain for the old left politics of groups that had historically emphasized work within organized labor. The Communist Party USA, the Socialist Workers’ Party, and others were widely perceived as reformist at best and corruptly reactionary at worst.

And of course the “official” labor movement was subject to even more stinging criticism and dismissal. As Carole Travis, a founding and long-time member of STO, emphasized, “no one thought that they [unions] were valuable to social change at all.”17 A lengthy campaign to bureaucratize the labor movement simultaneously purged almost all major unions of openly radical voices, a process eagerly supported by the US government under the auspices of anti-Communism.18 The merger of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) in 1955 had cemented the commitment of mainstream labor unions to labor peace. By the late sixties, the AFL-CIO was one of the most reactionary entities in US politics, with a membership that largely supported the Vietnam War, opposed civil rights and women’s liberation, and routinely tolerated corrupt sweetheart agreements with employers. The leadership had ties to the CIA and to the mafia, and the rank and file was largely dismissed by the left as having no revolutionary potential. Weatherman, the wing of SDS that would later be known as the Weather Underground, argued in its initial political statement that “unionized skilled workers” had “a higher level of privilege relative to the oppressed colonies, including the blacks, and relative to more oppressed workers in the mother country; so that there is a strong material basis for racism and loyalty to the system,” and by the fall of 1969 the group had embraced the slogan “fight the people,” with only a tinge of irony.19 While other radicals harshly criticized this line, it was in many ways only a slightly exaggerated reflection of the positions held by much of the revolutionary left at the end of the decade.

Against this backdrop, only a small number of radicals gave any serious thought to engaging in workplace organizing. Nonetheless, under the very noses of a largely ignorant new left, explosive labor struggles were taking place in an array of industries across the country. Many, perhaps most, of these fights pitted rank and file workers against both the management and the union leadership, resulting in a growing wave of wildcat strikes like the one that spawned DRUM in 1968.20 From bus drivers and postal workers to machinists and longshoremen, the working class was becoming increasingly aware of its own power, as opposed to the supposed power of its self-proclaimed representatives. This was true both in the US and elsewhere, as the French general strike of 1968 and the Italian Hot Autumn of 1969 indicated.21 To the small minority of the left that was paying attention, workplace struggles began to seem full of revolutionary potential.

One factor that influenced this assessment was the relatively integrated character of many larger workplaces in the United States, especially in heavy industry and some service-sector work (such as hospitals and transportation). Racism was certainly an inescapable reality for black and latino workers, who routinely received the worst paid, least safe, and least secure jobs in any factory, assuming they were able to find employment at all in the face of double-digit unemployment for nonwhites, especially youth.22 Once on the job, however, workers of color brought with them the lessons learned from two decades of the civil rights movement. And in many cases, they were able to teach these lessons to disaffected younger whites who increasingly saw the limits of individual attempts at rebellion in the form of long hair and dope smoking.

For both black and white young men in the working class, the war in Vietnam represented the ever-present threat of draft and death. For those who survived their tour of duty, factory bosses often became the object of residual anger that had previously been targeted at commanding officers. The result was an increase in shop floor militancy, a willingness to confront perceived injustice and demand change, and an openness to radical perspectives. It’s likely that only a handful of the workers involved in wildcats and other struggles went into them with anything like an anticapitalist worldview, but more than a few emerged as committed revolutionaries with remarkable organizing experience and a strong sense of solidarity.

One segment of the new left, including many of the people who would go on to found STO at the end of 1969, took an interest in this underpublicized movement, especially once groups like DRUM and the LRBW used recognizably revolutionary rhetoric to describe struggles that might otherwise have seemed reformist in spite of their militancy. Upon reflection, the wave of wildcats could be seen as a validation of two traditional insights of Marxism. First, the fact that they took place outside the union structure was a confirmation of the longstanding radical claim that “the emancipation of the working classes must be conquered by the working classes themselves,” rather than the work of trade union bureaucracies.23 Second, the factory was able to “discipline” workers, teaching them solidarity and cooperation even while it imposed competition and division. Insurgent organizing efforts served as experience that helped prepare the working class to run society. While few if any of the wildcats of the late sixties and early seventies resulted in factory occupations, much less the continuation of production under worker control, this was a presumptive next step that was much discussed by revolutionaries both inside and outside the workplace.

* * *

If conflict at the point of production was intensifying as the sixties came to a close, conflict around the war in Southeast Asia was even more explosive. This was perhaps the only arena in which the momentum of the new left did not falter in 1969, despite the confused character of the increasingly disparate antiwar movement. Demonstrations continued to draw enormous crowds, just as they had in preceding years. Direct actions against draft boards and military recruitment offices became more frequent and more violent. The number of draft resisters continued to rise as young men fled to Canada and elsewhere to avoid induction. Perhaps more important, resistance within the military became more pronounced and more radical. The number of fraggings (violent assaults on commanding officers, often using fragmentation grenades with intent to kill) skyrocketed in 1969, and the number of desertions increased dramatically over the previous year.24

In short, the antiwar movement was becoming more proletarian in its orientation, as young working-class enlisted men and their families began to question the war effort. Just a few years before, opposition to the Vietnam War had been confined to the middle class, and especially to student radicals at more or less prestigious universities and to religiously oriented progressives. There had always been a strong moral component to the antiwar movement, partly inherited from the pacifist legacy of previous movements during Korea and World War Two.25 But as the Vietnam War became less and less popular with mainstream Americans, the moral basis of the antiwar movement became something of a stumbling block. Draft dodging and counter-recruitment, for instance, could be ridiculed as middle-class escapism and patronizing missionary work, respectively.

The increasing radicalism of the student left, coupled with its rapid expansion into the realm of second tier state universities and community colleges, provided an opening in which connections could be built across the class divide. Once again, the black movement was the fulcrum point, as civil rights veterans began to turn their attentions to the racism of the draft and the parallels between the experience of African Americans and that of the Vietnamese. Martin Luther King famously spoke out in opposition to the war shortly before his assassination in 1968, and the world champion boxer Muhammad Ali refused military service as early as 1966, saying “I’m not going 10,000 miles from home to help murder and burn another poor nation simply to continue the domination of white slave masters of the darker people the world over.”26 Racism inside the military may also have helped to radicalize the GI resistance movement: some activists believed that white enlisted men were being forced to choose between white supremacy and class solidarity as they decided whether to side with largely black deserters or their mostly white commanding officers.27

Unfortunately, the radical potential of a broad-based antiwar movement was undercut at the end of the sixties by several factors, chief among them the internalized white supremacy of the white working class and the ascension of Richard Nixon to the presidency in 1969 on a supposedly antiwar platform. In contrast to the student movement, which was headed toward the pro-Vietcong stance best typified by Weathermen marching at the Days of Rage in Chicago with Vietnamese National Liberation Front (NLF) flags, the mainstream antiwar movement was always couched in the language of patriotism.28 On one level this was yet another legacy of the civil rights movement, which had, for the most part, considered inclusion of blacks as full citizens to be a truly American goal. But a bigger issue was the insidious nature of white supremacy and imperialism. Except for a small core of revolutionaries, most white people opposed the war out of concern for the safety and well-being of young white men in the US military. The cost of the war on the people and land of Vietnam, and even upon black and latino soldiers, were of only marginal concern at best. This racism also influenced mainstream responses to draft dodging and GI resistance. Young men fleeing to Canada (mostly white) received a fair bit of positive press coverage, while those participating in army rebellions (often black) were either ignored or denounced.29

Richard Nixon was elected president in 1968, and his “southern strategy” of appealing to white racial resentment of the civil rights movement only reconfirmed the tight grip of white supremacy on the electoral process.30 In the context of the campaign, however, Nixon actually came to represent a certain type of antiwar sentiment. Without any specifics, he promised a new approach to the war in Vietnam, which was known as the “secret plan.” Given the growing distaste among white liberals for the war’s rising death toll, Nixon represented a change from five years of escalating involvement in Vietnam under Lyndon Johnson. Despite some late efforts to distance himself from Johnson’s policy, Hubert Humphrey represented, for many people, a Democratic Party committed to staying the course. While mainstream opposition to the war was increasing, it found an unfortunate outlet in support for Nixon.

The result was a confused antiwar movement, which in 1969 encompassed both white, racist Nixon supporters in the south and black revolutionaries killing their CO’s in Vietnam, white revolutionaries flying Vietcong flags in Chicago and black civil rights leaders across the country still tied to a floundering Democratic Party. Great opportunities were overlaid with huge internal disagreements, and the radicals who would found STO at the end of the year were most likely at a loss for how best to proceed.

* * *

One social movement of the late sixties, the women’s movement, cut across the grain of the others. Initially an outgrowth of women’s involvement in the civil rights movement and the new left, by 1969 feminists had begun to challenge male supremacy not only in mainstream society but also within the left as well. The available targets were so many and varied that the result was a women’s liberation movement whose ideological diversity nearly matched that of the antiwar milieu. It included everyone from lesbian separatists to revolutionary communists to budding capitalist functionaries. While these internal contradictions wouldn’t become unresolvable until the early seventies, they were already exerting a complicated effect on the new left as a whole.

There were at least three versions of feminism in the United States during the late sixties, which might be termed liberal feminism, radical feminism, and feminist radicalism.31 The first of these was to become in many ways the defining aspect of the movement, as middle-class, white women struggled to gain entry to the male power structure. Corporate jobs, professional careers, access to the military, and the right to work full time instead of being at home with the children—these were the primary goals of liberal feminists. The presumption was that women—at least, white, middle-class women—could be integrated successfully into the economic sphere without jeopardizing the health of capitalism. It turns out that they were right, even though wage disparities persist for women and men in equivalent jobs. With the possible exception of some Marxists who viewed this integration as a stepping stone toward the creation of a fully bourgeois society that would then inevitably be toppled by proletarian revolution, almost no one in the new left, men or women, had any use for liberal feminism.

The distinction between radical feminism and feminist radicalism, as the names suggest, was largely one of emphasis. Both camps rejected liberalism and looked toward fundamental social change as a necessity for women’s liberation. But where feminist radicals tied the success of feminism to the broader project of social revolution, radical feminists saw the oppression of women as the root of social ills ranging from war to capitalism. This led radical feminists to criticize, and in some cases to reject outright, the rest of the left as a bastion of male supremacy and a detour from the essential work of freeing women as women.32 This approach was always double-edged. On the one hand, it produced brilliant insights into the nature of oppression and resistance: the claim that “the personal is political,” for instance, and the use of consciousness raising as a way to organize women in all spheres of life. Similarly, the critique of sexism and macho behavior within the new left, typified in essays like Marge Piercy’s “Grand Coolie Damn,” was clearly on target. She began her essay by noting that

the Movement is supposed to be for human liberation. How come the condition of women inside it is no better than outside? We have been trying to educate and agitate around women’s liberation for several years. How come things are getting worse? Women’s liberation has raised the level of consciousness around a set of issues and given some women a respite from the incessant exploitation, invisibility, and being put down. But several forces have been acting on the Movement to make the situation of women actually worse during the same time that more women are becoming aware of their oppression.33

At the same time, the prioritization of women’s supposedly common experience as women underplayed the divisions between the lives of women of different backgrounds (black and white, poor and rich, young and old, lesbian and straight, etc.). This blindspot alienated many working-class women who otherwise might well have been open to the insights feminism had to offer. As a result, the work of radical feminists began to reflect more and more narrowly the lived experience of white, middle-class, educated women.34 The trajectory from here to liberalism was never foregone, but neither is it hard to divine.

By contrast, feminist radicals emphasized the need to include women’s issues within the overall analysis of the new left. Without ignoring the problems of sexism in broader social movements, they argued that women’s problems could not be solved without simultaneously addressing racism, the war, and what new leftists called “the system.”35 For a number of women, including several founders of STO, this meant first and foremost addressing the concerns of working-class women, women of color, and the women of Vietnam. In doing so, it became clear that many of these issues—poverty and discrimination in the black community, for instance, or war crimes in Southeast Asia—were primarily about race and class, and only secondarily about sex. From this perspective, the limits of the radical feminist worldview seemed increasingly frustrating to the feminist radicals. In some cases, this led to a baby and bathwater sort of reaction, where even the important lessons of consciousness raising were dismissed as middle-class diversions.36 The personal might be political, but women doing ten-hour piecework shifts in textile factories have more urgent problems than being forced to conform to men’s standards of beauty. The solution, according to the feminist radicals, was social revolution with a feminist twist.

Another, tangentially related development in 1969 was the birth of the modern gay rights movement during the Stonewall rebellion in New York City. On the night of June 27, police raided the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, continuing a longstanding tradition of harassing gay men, lesbians, and drag queens in one of the only places they could then congregate.37 For reasons that are still disputed today, the patrons resisted the police, and successfully forced them to retreat in fear for their own safety. In one of the most heavily queer neighborhoods in the United States, this small altercation quickly blossomed into a full scale riot during which 2,000 or more angry gays and lesbians fought several hundred police officers for control of the streets. At least two more nights of fighting followed, and the movement for gay and lesbian liberation burst upon the scene, taking obvious inspiration from both the black and feminist movements in its combination of consciousness raising and militant street tactics.

In later years, the lesbian and gay liberation movement would fracture under the strain of divisions similar to those encountered by the women’s movement of the late sixties. Nonetheless, both gay and lesbian liberation and feminism were sources of great enthusiasm and optimism (as well as dread and derision) on the left as the decade came to a close. The strategic choices implied by the various tendencies within both movements ensured that no one could predict what the seventies had in store for feminism or for the gay movement.

* * *

A striking number of feminists, if only a limited segment of the gay and lesbian movement, cut their teeth on the student movement of the sixties, especially within Students for a Democratic Society.38 SDS had grown dramatically over the course of the decade, from a small organization of progressive students at mostly elite universities to a massive network of radical youth from all walks of life, including many who were not even students. But expansion led also to heightened disagreement over politics and strategy. Regular meetings of the group in the late sixties were marked by ever more bitter argument between two leading factions: the Worker Student Alliance and the Revolutionary Youth Movement. At the annual SDS convention in Chicago in June of 1969, the conflict split the group, effectively destroying what had been the largest formation within the new left and leaving the student movement in near total disarray.

The Worker Student Alliance was a front group for the Progressive Labor (PL) Party, which was the newest of the old left parties, having been founded in 1961 by dissidents leaving the CPUSA.39 From the start, PL had prioritized work on campuses, and by the mid-sixties it had begun sending members into SDS. Around the same time, the leadership of PL began to advocate a pro-working-class strategy (hence the name “Worker Student Alliance”) that criticized nationalism both in the black community and in Vietnam. Instead, PL argued for a combination of unite-and-fight approaches to labor struggles in the US and Maoist internationalism abroad. Their deference to Mao and to the working class brought them a certain amount of credibility within SDS, but their version of antiracism led to significant criticism. Among the initial opponents of PL’s strategy was Noel Ignatin, later to become one of the founders of STO, whose open letter to PL was published—along with a sympathetic response from Ted Allen to Ignatin—under the title “The White Blindspot” in 1967.40 Ignatin argued that PL inappropriately separated the struggle for black liberation from the efforts of the working class to overthrow capitalism, as if the former were merely a set of liberal reforms needed before the latter could be fully implemented.

“The White Blindspot” was the first written formulation of the analysis of white supremacy that would characterize STO throughout its existence. In it, Ignatin and Allen argued for the centrality of struggles against white supremacy in any working-class context. In particular, emphasis was placed on the need to combat white skin privileges, which in the view of the authors poisoned the well of working-class solidarity. The burden was squarely on the shoulders of white workers to adopt the demands of black workers as their own, not simply incorporate some antiracist rhetoric into otherwise white-led efforts.

While certainly controversial in its own right, Ignatin’s view was welcomed by the anti-PL forces within SDS. In fact, Ignatin was recruited to join SDS partly on the basis of his letter, despite the fact that he was a factory worker not enrolled in any school.41 By the time of the fatal conference two years later, one or another version of the white skin privilege line had been more or less adopted by a variety of people in SDS, including a small but significant faction of the SDS leadership, which coalesced primarily around opposition to PL and support for black movements. This faction took the name Revolutionary Youth Movement (RYM), and managed briefly to paper over its own glaring disagreements, long enough to expel the PL members from SDS through a set of procedural moves that were awkward at best and antidemocratic at worst.

Once the split in SDS was final, the conflicts within RYM came to the surface, with the Weatherman faction (briefly known as RYM I) retaining control of the formal apparatus of the group long enough to finally run it into the ground on their way to clandestinity. Opposing their efforts, if only half-heartedly, was the RYM II faction, which agreed on opposition to PL and Weather, and support for an orientation toward the working class, but not on much else. The collapse of SDS had soured RYM II on student struggles, and attention increasingly turned toward workplace and community organizing. But once again, political differences made RYM II short-lived, as it disintegrated after its only conference, in Atlanta in November, 1969 (which was attended by several of the soon-to-be founders of STO). Putting to one side the continuing efforts of PL to maintain what it called the “real” SDS, the organized student movement was dead by the end of the year, and even though hundreds of campuses would erupt the following spring in anger over the bombing of Cambodia, the linkages between STO and the campus left had been more or less permanently sundered before the group was even founded.

* * *

In many ways, Chicago represented a microcosm of the left at the end of the sixties. Each movement described here was on display, and in several cases Chicago was something of an advanced laboratory for left trajectories that would later become more widespread. The city’s large size, economic vitality, and geographic location between the coasts helped ensure that it was a place people moved to from elsewhere in the country. For the new left, this centrality was augmented by two factors: first, the presence of the SDS National Office in Chicago guaranteed that participants in the most advanced sectors of the white left visited frequently, and in many cases moved there temporarily or permanently.42 Second, the infamous events surrounding the 1968 Democratic National Convention put Chicago on the map as an important center for militant social struggles. Not surprisingly, the founding members of STO represented something of a cross-section of the movements of the sixties, all based in the city of big shoulders.

Among the leaders of the RYM II faction of SDS who called Chicago home in 1969 was Noel Ignatin, who, as mentioned previously, was responsible for the initial articulation of what became STO’s line on white supremacy and white skin privilege. His background included time spent in old left cadre organizations, and, as he recalled later, “I myself was still a Stalinist, with several important reservations.”43 He was heavily influenced by the writings of W.E.B. Du Bois, especially the landmark study Black Reconstruction, from which he drew the title for his polemic against PL.44 Ignatin’s attachment to Stalinism was challenged by C.L.R. James, who was living temporarily in Chicago in 1968. At the invitation of his friend Ken Lawrence (who would himself join STO in the mid-seventies), Ignatin attended a public speech by James and came away impressed.45 James had made the opposition to Stalinism one of the two pillars of his political outlook, along with the opposition to white supremacy.46 Ignatin agreed with the latter, and as the decade ended he found himself more and more in agreement with the former. As late as fall 1969, he could still criticize the Weatherman faction of SDS by favorably referencing the leading role of “Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and Mao.”47 Nonetheless, given his encounters with PL, his experience inside SDS, and the rapidly changing political environment, Ignatin’s move toward anti-Stalinism was swift.

In addition, Ignatin had years of direct experience with factory work, which gave him additional prestige as RYM II moved closer to a working-class orientation. By 1969, he was working at the International Harvester (IH) Plant on the southwest side of Chicago.48 When IH announced the impending closure of the plant (in a little-noticed sign of the massive deindustrialization that was to come), Ignatin attempted to combine in-plant organizing with the support of movement people. On the same weekend in October that the Weatherman faction had called for Days of Rage, the RYM II faction held a series of nonconfrontational protests designed to showcase their commitment to the working class.49 One of these protests was held at the gates of the IH plant, which nonetheless closed its doors for good some months later and was eventually replaced by an expansion of the Cook County Jail.50

Three other founding members of STO, Marilyn Katz and Evie and Mike Goldfield, were also veterans of SDS. Katz had been actively involved in planning the protests at the 1968 Democratic Convention, as part of the tactical team that coordinated security and demonstration marshals.51 She was specifically identified by prosecution witnesses during the Chicago Seven trial, although she was never charged.52 Her expertise in the area of movement defense was enhanced by her relationship with another founding member, Bob Duggan, a martial arts trainer whose background supposedly included extensive experience in semi-underground revolutionary formations in Latin America.53

The Goldfields had lengthy experience with SDS, including work with the Radical Education Project (REP) of the mid-sixties, and active involvement in the student protests against the firing of feminist radical professor Marlene Dixon from the University of Chicago in late 1968.54 These protests had led to the occupation of an administration building in early 1969 and the expulsion of dozens of students. Mike Goldfield was also employed at the International Harvester plant with Ignatin, and was enthusiastic about organizing at the point of production.55

In addition to her participation in SDS, Evie Goldfield was also active in the feminist movement, both within and outside of SDS. She was the co-author of a number of pamphlets and essays, including Toward a Radical Movement, published in April 1968.56 The perspective of this piece is clearly aligned with that of feminist radicalism, as the pamphlet ties together “women’s liberation and the liberation of all people.” Further, the essay highlights the plight of working-class women and women of color, while still addressing the concerns of middle-class alienation and general issues of women’s oppression by social roles.

At least one other founding member of STO was involved in the women’s movement in Chicago: Hilda Vasquez Ignatin, wife of Noel, was a contact person in the late sixties for a Chicago-based newsletter called The Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement.57 Despite being of Mexican ancestry, she was also a prominent member of the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican revolutionary organization that had been founded as a street gang in Chicago in the early sixties.58 By the time Vasquez Ignatin was involved, the group had undergone its political transformation and had expanded geographically to include radical Puerto Ricans in New York City and elsewhere. Her role in leadership was indicated by her selection to speak on behalf of the Young Lords at a rally during the RYM II demonstrations that fall.59

On the other hand, at least two female founders of STO, Lynn French and Carole Travis, did not have extensive involvement with the women’s movement, although they had their own areas of experience on the left. French was a member of the Illinois Black Panther Party, headed by Fred Hampton until his murder in December, 1969. Under Hampton, the Illinois BPP was one of the most vibrant sections of the Party nationwide. It developed ongoing (though not always smooth) relations with the SDS national office, and with activist groups in other communities that were modeled in part on the Panthers, such as the Young Lords Organization in the Puerto Rican community, and the Young Patriots, who were active in the community of Appalachian whites who had immigrated to Chicago over the course of the sixties.60 French recalls that she had been arrested shortly before Hampton was killed, “so I was in Cook County Jail and did not get out until some time after the funeral. I’d been beaten and sustained leg injuries that still cause me problems. I went east to [stay with] my parents for a few weeks, and gave a lot of thought to whether or not I would return to the BPP.… Although I ultimately returned to the Party, I was involved in the founding of [STO] during the interim.”61 She also proposed the name “Sojourner Truth Organization,” after the former slave, abolitionist, and women’s rights activist of the nineteenth century.62 The name stuck with the group long after French departed, and despite the almost all-white demographics of the membership throughout its history.

Carole Travis was an antiwar activist whose main frame of reference was antiracism and a commitment to the working class. For a time she was on staff at the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam.63 Travis’s father was Bob Travis, an active militant in the Communist Party who had led the Flint Sit-Down Strike of 1937, which was pivotal in organizing the auto industry and gave incredible momentum to the newly founded CIO.64 “I grew up with my mother,” Travis recalls. “She was more of a New Deal Democrat, although she was a genius and critical of everything, and she had a good sense of humor and was crazy.”65 She embraced her mother’s opposition to racism, but she also retained her father’s commitment to the industrial working class. The militant struggles at the grassroots that characterized the Flint strike and other early CIO efforts were a major influence on the initial workplace organizing of STO in the early seventies.

Sometime in the late sixties, Travis met and married Don Hamerquist, who was to become the only person involved with STO throughout the group’s existence. At the time of their meeting, Hamerquist was an emerging young star of the CPUSA. He had recently relocated from the west coast to Chicago in order to participate in the planning of the protests around the 1968 Convention.66 He had been favorably profiled in Time magazine, and was rumored to be Gus Hall’s pick to replace him as head of the Party.67 But things changed: Hamerquist was profoundly influenced by the new left, and was dismayed by the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. His biggest political influence was Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, whose writings were newly translated into English in the mid-sixties.68 Gramsci’s analysis of hegemony and consciousness, and his commitment to the workers’ councils as the basis of communist power, were to be hallmarks of STO’s analysis throughout its existence.

Hamerquist and others briefly attempted the equivalent of a coup in the Party, advancing an alternative political program and convincing many younger radicals to join the party in an attempt to elect a new leadership slate. Having lost this effort, he quit before the Party could expel him, and set his sights on next steps.69 He and Travis remained in Chicago, immersed themselves in factory work, and began developing the analysis of dual consciousness that would mark STO from the start. Their disillusionment with the CPUSA also led them to a critique of Stalinism that meshed well with the Jamesian approach that Ignatin was developing around the same time.

One additional person deserves mention here. Ken Lawrence, as mentioned above, was not a founding member of STO, partly because in 1969 he was still a member of the not-yet-defunct Facing Reality Organization, led by James and coordinated by Martin Glaberman in Detroit.70 Lawrence had also played a role in the small resurgence of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) a few years earlier, and found himself profoundly influenced by the legacy of the original Wobblies.71 This connection no doubt had some responsibility for the development of STO’s initial “Call to Organize,” which begins by quoting the famous first sentence of the Preamble to the IWW Constitution: “The working class and the employing class have nothing in common.”72 Lawrence also had extensive experience in the civil rights movement, and through Facing Reality was familiar with the development of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. By the late sixties, Lawrence was a familiar face to several of those who did participate in the creation of STO, and his influence was significant on the early trajectory of the group.

In short, the founding members of STO were in some ways as diverse as the movements from which they emerged: men and women, mostly white but with black and latino participation as well, largely young and inspired by the new left of the sixties, but also with ties to the old left of the CPUSA and its various splits and imitators. The result was an eclectic mix of experiences and perspectives, which bore some similarity to the emergence of other groups in what became known as the New Communist Movement, while retaining a uniqueness that persisted over the course of the next two decades.73

* * *

The initial rumblings of what became the Sojourner Truth Organization lie in the RYM II conference in Atlanta, over Thanksgiving weekend of 1969. In advance of the conference, a small grouping of revolutionaries, including the people described above, had begun meeting in Chicago to discuss the future of the movement, broadly speaking.74 As indicated, they took inspiration from the Leninist tradition, both in the US and around the world. The grouping drafted a paper to distribute at the Atlanta convention, advocating the creation of a Marxist-Leninist party as a key task for the coming period. The Atlanta paper identified several key attributes that were necessary if the new party was to succeed. It needed a theory and a line that could guide a comprehensive revolutionary strategy for the United States; that theory was Marxism-Leninism, and the line was the emerging analysis of white skin privilege. The line had to be tested in practice, and in particular it was necessary to be sure that success was a result of the line, not of the efforts made by individual leaders of the party. The party had to succeed in recruiting workers, not simply students or middle-class intellectuals, and including these workers in the leadership. The membership needed to reflect the demographics of the US population, and it had to be a presence in “the most important industrial centers of the country.” Finally, it needed a sizeable and supportive periphery, people who wouldn’t join the party but “were happy to see it formed.”75

In this, the Chicago grouping was on the same page as most of the other RYM II formations. The hosts in Atlanta, for example, were in the process of forming the Georgia Communist League, which also looked toward the creation of a new party. But the similarities largely stopped there, as the Chicago grouping took far greater interest than any other RYM II groupings in mass (as opposed to cadre) revolutionary formations, in the development of revolutionary consciousness through collective action, and in the repudiation of Stalinism.76 Further, STO’s understanding of the white skin privilege line differed significantly from the analysis adopted by most of the other RYM II groups, some of which eventually repudiated the line completely as the seventies progressed.77

The Chicago grouping continued to meet after the Atlanta conference, despite the fact that RYM II was clearly doomed. By the end of the year, the collective decided to act on the paper it had produced and constitute itself as a formal organization that would act like a party on a small scale.78 Just after Christmas, the Sojourner Truth Communist Organization was born. (The word “Communist” was “allow[ed] … to fall into disuse” about a year later.)79 A meeting schedule was agreed upon, dues were collected, and two areas of work were prioritized: workplace organizing focused on producing an underground in-factory newsletter as part of the campaign to keep the International Harvester plant open, and community organizing efforts were dedicated to winning the release of a young black man who had been framed on a murder charge. The SDS/RYM/RYM II experience had left a bitter aftertaste in the mouths of STO’s founders, and initially the group avoided contact with the rest of the self-identified left, preferring direct immersion in working-class communities. Although this policy was soon reversed, the insistence on mass work as opposed to a simplistic reliance on left coalition-building efforts was a continuing theme within the organization.

Over the course of the next fifteen or more years, STO would go through innumerable changes in membership; only Hamerquist, Ignatin, Travis, and Katz (as well as Lawrence) would play any significant role after 1973. The political transformations the group would undergo as the years progressed were even more important. The first major period of the group’s existence, roughly from 1970 until 1975, saw the development of STO’s initial ideas around the centrality of working-class experience (Chapter Two) and the opposition to white supremacy (Chapter Three), as well as the group’s initial efforts to develop an organization that could sustain the fight for revolution in changing circumstances. It is to the practical and theoretical implications of these concepts, workers and whiteness in the context of revolutionary strategy, that we turn next.

7 For more on the shift from civil rights to black power modes of the black freedom movement, see Peniel E. Joseph, Waiting ’Til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006).

8 For more on COINTELPRO operations against the black movement, the white left, and the far right, see David Cunningham, There’s Something Happening Here: The New Left, the Klan, and FBI Counterintelligence (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2004).

9 The influence of the Panthers, and black radicalism generally, on the white left of the late sixties is detailed in David Barber, A Hard Rain Fell: SDS and Why It Failed (Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2008).

10 On the Panther 21, see Murray Kempton, The Briar Patch: The Trial of the Panther 21 (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1997 [1973]).

11 The best work on Hampton’s killing is Jeffrey Haas, The Assassination of Fred Hampton: How the FBI and the Chicago Police Murdered a Black Panther (Chicago: Lawrence Hill Books/Chicago Review Press, 2010).

12 The split in the Party is detailed by Peniel Joseph, Midnight Hour, 261–269.

13 The classic assessment of the League is Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying: A Study in Urban Revolution (Updated Edition) (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 1998 [1975]).

14 See Chapter Two for more on the LRBW’s influence on STO.

15 Georgakas and Surkin describe the rise of DRUM and its connection to the emergence of the LRBW. Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, 20–41.

16 Carl Davidson, “Toward Institutional Resistance,” New Left Notes, November 13, 1967, quoted in David Barber, “‘A Fucking White Revolutionary Mass Movement’ and Other Fables of Whiteness,” Race Traitor no. 12, Spring 2001, 35. Davidson subsequently participated in the New Communist Movement throughout the seventies, including several years spent in the Harpers Ferry Organization, a small New York City group aligned with STO.

17 Carole Travis, interview with author, June 6, 2006.

18 This process is outlined in Kim Moody, An Injury to All: The Decline of American Unionism (New York: Verso, 1988), 45–51.

19 Karen Ashley, Bill Ayers, et. al., “You Don’t Need a Weatherman to Know Which Way the Wind Blows” (June 18, 1969), in Harold Jacobs, ed., Weatherman (Berkeley, CA: Ramparts Press, 1970), 66. “Fight the people” is discussed in favorable terms in Bill Ayers, “A Strategy to Win” (September 11, 1969) in Jacobs, 192.

20 For more on labor unrest in the late sixties and early seventies, see Aaron Brenner, Robert Brenner, and Cal Wislow, eds., Rebel Rank and File: Labor Militancy and Revolt from Below During the Long 1970s (New York: Verso, 2010).

21 These events are described in greater detail in Chapter Two.

22 According to economists Peter Jackson and Edward Montgomery, the unemployment rate for black men between the ages of eighteen and nineteen was 19 percent, more than double the 7.9 percent for white men of the same ages. Peter Jackson and Edward Montgomery, “Layoffs, Discharges and Youth Unemployment,” in Richard B. Freeman and Harry J. Holzer, eds., The Black Youth Employment Crisis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 116.

23 This particular phrasing comes from the “General Rules” of the International Workingmen’s Association, adopted in October 1964. Available online at http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/iwma/documents/1864/rules.htm (accessed January 7, 2012).

24 The classic work on GI resistance in Vietnam remains David Cortright, Soldiers in Revolt: GI Resistance During the Vietnam War (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2005 [1975]). For a thorough, if pro-military, look at fragging, see George Lepre, Fragging: Why US Soldiers Assaulted Their Officers in Vietnam (Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech University Press, 2011).

25 James Tracy, Direct Action: Radical Pacifism from the Union Eight to the Chicago Seven (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996) describes this historical development through the end of 1969.

26 Quoted in Mike Marqusee, Redemption Song: Muhammad Ali and the Spirit of the Sixties (New York: Verso, 1999), 214–215.

27 George Schmidt, interview with the author, March 26, 2006.

28 Dan Berger, Outlaws of America: The Weather Underground and the Politics of Solidarity (Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2006) 99–104, describes Weather’s support for the NLF; the cover of the book features a photo of Weatherman women marching with NLF flags in 1969.

29 George Schmidt, interview with the author, March 26, 2006.

30 James Boyd, “Nixon’s Southern Strategy: ‘It’s All in the Charts’,” New York Times, May 17, 1970.

31 These distinctions are artificial and a bit arbitrary, but are largely consistent with the taxonomy offered by the philosopher Alison Jaggar in her pioneering work Feminist Politics and Human Nature (Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield, 1988 [1983]). My usage of “feminist radicals” tracks generally with Jaggar’s category of “socialist feminists.” Ellen Willis, in a fascinating memoir-style reflection on the twists and turns of sixties and seventies feminism, uses the title “Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism.” While she fails to define the latter term, her analysis is similar to mine. Ellen Willis, “Radical Feminism and Feminist Radicalism,” Social Text no. 9/10 (1984), 91–118.

32 For a key example of this line of thinking, see Robin Morgan, “Goodbye to All That” (1970), in Rosalyn Baxandall and Linda Gordon, eds., Dear Sisters: Dispatches From the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: Basic Books, 2000), 53–57.

33 Marge Piercy, “The Grand Coolie Damn,” Leviathan Magazine, November, 1969. Available online at http://www.cwluherstory.com/the-grand-coolie-damn.html (accessed January 8, 2012). Piercy is one of many feminists of the era whose complex views highlight the limits of the distinction between the feminist radicals and the radical feminists.

34 The historian Alice Echols frames this problem in terms of the rise of cultural feminism during the early seventies. Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967–1975 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989). Some of the internal struggles around questions of class and race within the feminist movement are described on pages 204–210 and 291–293.

35 Heather Booth, Evi Goldfield, and Sue Munaker, Toward a Radical Movement (Somerville, MA: New England Free Press, 1968) represents an early version of this analysis. Goldfield was subsequently a founding member of STO. Available online at http://www.cwluherstory.com/toward-a-radical-movement.html (accessed January 8, 2012).

36 Carole Travis, a founding and long-time member of STO, attributes this view to herself at the end of the sixties. Interview with the author, June 6, 2006.

37 For more on Stonewall, see Martin Duberman, Stonewall (New York: Dutton, 1993) and David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution (New York: St. Martins Griffin, 2005).

38 The most comprehensive historical account of SDS remains Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS (New York: Random House, 1973).

39 In addition to Sale, background on the origins of PL and its subsequent involvement in SDS can be found in Dan Berger, Outlaws of America, 75–91, and Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air: Sixties Radicals Turn to Lenin, Mao and Che (New York: Verso, 2002), 63–64 and 69–72. My account of these events is based on these three renderings.

40 Noel Ignatin and Ted Allen, “The White Blindspot,” in Understanding and Fighting White Supremacy (Chicago: STO, 1976). This document was published repeatedly between 1967 and the mid-seventies. Sometime after his departure from STO in the mid-eighties, Noel Ignatin changed his name to Noel Ignatiev. For the sake of consistency, I will use “Ignatin” in reference to any document or activity that he was associated with during his time in STO, and reserve “Ignatiev” for statements made after his departure from the group.

41 Noel Ignatiev, interview with the author, January 27, 2006.

42 Sale describes the role of Chicago’s SDS head office repeatedly in his book, beginning in the “Fall 1965” section and continuing throughout.

43 Noel Ignatin, “The POC: A Personal Memoir,” Theoretical Review #12, September/October 1979. Available online at http://www.marxists.org/history/erol/1956-1960/ignatin01.htm (accessed January 9, 2012) The Provisional Organizing Committee to Reconstitute the Marxist Leninist Communist Party USA (or POC) was a small Stalinist splinter from the CPUSA formed in the late fifties.

44 W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860–1880 (New York: Free Press, 1998 [1935]).

45 Noel Ignatin, “Meeting in Chicago,” Urgent Tasks #12, Summer 1981, 126–127.

46 C.L.R. James, State Capitalism and World Revolution (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 1986 [1950]), written in collaboration with Raya Dunayevskaya and Grace Lee, represents the most comprehensive of James’s many attacks on Stalinism.

47 Noel Ignatin, “Without a Science of Navigation We Cannot Sail in Stormy Seas, or, Sooner or Later One of Us Must Know,” in The Debate Within SDS: RYM II vs. Weatherman (Detroit: Radical Education Project, September, 1969).

48 Noel Ignatiev, interview with the author, January 27, 2006.

49 Sale details this sequence of actions in the section “Fall 1969.”

50 Noel Ignatiev, interview with the author, January 27, 2006.

51 John Kifner, “28-Year-Old Snapshots Are Still Vivid, and Still Violent,” New York Times, August 26, 1996.

52 The testimony of William Frapolly, an undercover investigator and prosecution witness during the trial, presents the government’s view of Katz’s role in the protests. Available online at http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/FTrials/Chicago7/Chi7_trial.html (accessed January 9, 2012)

53 Duggan subsequently became publicly identified with right-wing politics and founded a training school for elite bodyguards serving corporate executives and government officials, Executive Security International. A hagiographic capsule biography can be found online at http://www.esi-lifeforce.com/about-us/faculty/bob-duggan.html (accessed January 9, 2012). Duggan’s apparent political shift may have been more extreme than that of any other former member of STO.

54 Sale identifies both Goldfields as participating in the REP in the fall of 1966. For more on the struggles around Marlene Dixon, see Arthur Hochberg, “U of Chicago Students Seize Building, Protest Woman’s Firing,” New Left Notes, February 5, 1969.

55 Noel Ignatiev, interview with the author, January 27, 2006.

56 Heather Booth, Evi Goldfield, and Sue Munaker, Toward a Radical Movement (Somerville, MA: New England Free Press, 1968).

57 Ignatin’s name appears on the inside front cover of Beverly Jones and Judith Brown, Toward a Female Liberation Movement (Somerville, MA: New England Free Press, 1968), in author’s possession.

58 Her role in the Young Lords is confirmed in both Jeffrey Haas, The Assassination of Fred Hampton, 47, and Lilia Fernandez, Latina/o Migration and Community Formation in Postwar Chicago: Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Gender, and Politics, 1945–1975 (PhD Diss., University of California, San Diego, 2005), 196. Fernandez’s dissertation represents the most detailed account of the origins and early development of the Young Lords in Chicago,

59 Young Lords Organization 1, no. 5 (January, 1970), 3.

60 See Amy Sonnie and James Tracy, Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times (Brooklyn, NY: Melville House Publishing, 2011), 66–100, for more on this process, normally labeled the original Rainbow Coalition.

61 Lynn French, email to the author, November 27, 2006.

62 Lynn French, email to the author, November 28, 2006. For more on Sojourner Truth, see Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996).

63 See the capsule biography of Travis used to honor her at an awards ceremony in 1994. Available online at http://www.chicagodsa.org/d1994/index.html (accessed January 9, 2012)

64 Studs Terkel, Hope Dies Last: Keeping the Faith in Difficult Times (New York: The New Press, 2003), 102–108.

65 Carole Travis, interview with the author, June 6, 2006.

66 Don Hamerquist, interview with the author, September 14, 2006.

67 “Oregon: Marxist From Multnomah,” Time, October 13, 1967.

68 Gramsci’s The Modern Prince had been available in English as early as 1957, but his pivotal essay “Soviets in Italy” appeared in New Left Review no. 51 (September/October, 1968), 28–58. STO would subsequently reprint this selection as a pamphlet.

69 Don Hamerquist, interview with the author, September 14, 2006.

70 Ken Lawrence, interview with the author, August 24, 2006.

71 J. Sakai, interview with the author, November 9, 2006. For more on Wobbly resurgence, see Franklin Rosemont and Charles Radcliffe, eds., Dancin’ in the Streets!: Anarchists, IWWs, Surrealists, Situationists and Provos in the 1960s, as Recorded in the Pages of The Rebel Worker and Heatwave (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005).

72 Don Hamerquist and Noel Ignatin, “A Call to Organize,” in Workplace Papers (Chicago: STO, 1980), 2.

73 For background on the New Communist Movement, see Max Elbaum, Revolution in the Air.

74 Much of what follows comes from two “Outline History of STO” documents, one from 1972, the other from 1981, both written largely by Noel Ignatin. The 1972 version is available online at http://www.marxists.org/history/erol/ncm-1/sto.htm (accessed January 9, 2012). The latter document in author’s possession.

75 “Outline History of STO” (1972).

76 These positions are clearly outlined in Toward a Revolutionary Party (Chicago: STO, 1976 [1971]), one of STO’s earliest political statements.

77 Kingsley Clarke recalls Bob Avakian, then of the Revolutionary Union, denouncing the white skin privilege line as “bankrupt, bankrupt, bankrupt” at a conference in 1974. Clarke, interview with the author, July 6, 2005.

78 “Outline History of STO” (1972).

79 “Outline History of STO” (1972). “Communist” was still in use as late as the publication of Bread and Roses in late 1970 or early 1971, but was missing from the first issue of the Insurgent Worker in May 1971.