Читать книгу Mythologies of State and Monopoly Power - Michael Tigar - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Mythologies, Mental Shortcuts, Impressions

THIS BOOK IS A COLLECTION of essays. Some of them focus on how mythologies mask state repression of democratic rights in the fields of racism, criminal justice, free expression, worker rights, and international human rights. Others deal with the ways that ordinary private law categories of property, contract, and tort perform the same social function.

Mythologies are structures of words and images that portray people, institutions, and events in ways that mask an underlying reality. In the days when France used the guillotine, the executioner cried, just after the blade dropped, “Au nom du peuple français, justice est faite.” In the name of the French people, justice is done. This cry had no rational relation to discourse about what is fair, right, decent, or in accord with evidence about conduct. “Justice” was a name given to an event, to elevate the act of killing into an acceptable and rational process.

To proclaim “Justice” committed two solecisms. First, it appropriated justice as the exclusive property of the state. Second, it assigned a fictitious value to the word, invoking a mythology of the universality of language.

In the United States, there is a department that calls itself Justice. Colloquially, we use the term “criminal justice system,” as though we are invited to ignore a system of endemic unfairness that has produced mass incarceration.

In 1957, the French writer Roland Barthes published a series of essays, under the title Mythologies. The book appeared in English under the same title in 1972.

Barthes’s essays describe the ways in which the state, the media, and private power wielders deploy verbal and pictorial images. Barthes writes of seeing a magazine cover in the late 1950s showing a black soldier saluting the French flag. At that time, France was engaged in brutal suppression of anti-colonial uprisings in Africa and had recently lost the decisive battle of Điện Biên Phû in Vietnam. The photograph sends the mythological message that even this soldier, and by extension most people of color, support colonialism.1

Another of Barthes’s essays discusses the trial of a semi-literate octogenarian French goatherd for killing an English tourist. The defendant did not possess the culpable mental state that the law’s machinery attributed to him. But, as Barthes observed:

Periodically, some trial, and not necessarily fictitious like the one in Camus’s The Stranger, comes to remind you that the Law is always prepared to lend you a spare brain in order to condemn you without remorse, and that, like Corneille, it depicts you as you should be, and not as you are.

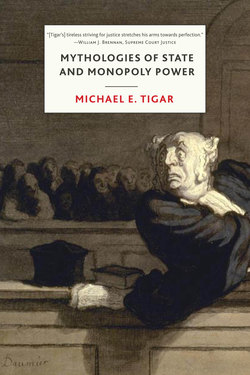

The nineteenth-century French artist Honoré Daumier penned a cartoon of a judge facing a defendant who had stolen food. “You were hungry?” the judge declaims. “You were hungry? I myself am hungry three times a day, and I don’t steal for that!”

Samuel Butler noted that parishioners in his church would be equally horrified at seeing the Christian religion doubted and at seeing it practiced.

In the United States, mythologies based on racial, ethnic, gender, and religious stereotypes drive discussions about social policy. Tom Paxton wrote of mythologies in the song “What Did You Learn in School Today?”: “I learned that Washington never told a lie / I learned that soldiers seldom die …”

We use mental shortcuts to get through our daily lives. We may know how to fry an egg. The routine is semi-automatic. We don’t think about every step. I need not think through all the decisions I make when crossing the street: Am I at the corner, is the WALK sign illuminated, are there cars coming, how high is the curb, and so on. I go through a series of internalized reactions, actions that “go without saying.” In New York City, of course, to hell with all that, I just barge across the street like everybody else.

Some mental shortcuts are stereotypes. We have a bad feeling about certain people based on their race, religious practices, choice of clothes, or any of a hundred different things. If I am in lower Manhattan, near the headquarters of Goldman Sachs, and I see a well-dressed white man coming out of the building, I will cross the street to get away from him. I fear he will rob me of my pension.

Many of these stereotypes are, when viewed rationally, indefensible. Yet, when they are challenged, we are likely to hold on to them more closely. This sort of thing is sometimes called “confirmation bias.” When we hold on to a position or idea in the face of contrary evidence, social science research terms this the “backfire effect.”2

An impression is our “take” on something we see. Claude Monet was an “impressionist” painter. He painted the same scene, for example, the Rouen Cathedral, over and over. Each of those paintings gives us a different impression of the same scene.

All of these terms, which I often use interchangeably, refer to ways of seeing and interpreting the world around us. As I say, most of them are harmless and even useful ways of getting through the day. Some, however, are ways we fool ourselves, or permit ourselves to be fooled, about what is really going on. William James said, “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices.”

In human rights litigation, and indeed in all law practice, we must deconstruct the myths that have grown up around our clients, the groups to which they belong, and the conduct attributed to them. Based on our client’s race, social class, sexual orientation, or some other characteristic, the state rationalizes its treating our client especially harshly.

When we litigate cases, we confront not only the evidence adduced and the legal principles being argued, but also the socially, culturally, and historically determined attitudes of judges and jurors. In a jury trial, we use voir dire to uncover those. We look up the biographies and prior decisions of judges.

I am a human rights lawyer. My most important task is to expose, analyze, and combat the mythologies that dominate legal ideology. These mythologies form a systematic justification for the way that state power and private economic power is wielded. The essays in this book focus on how mythologies may be understood and exposed. This “myth-busting” lies at the heart of the lawyer’s work. We undertake to represent clients who are marginalized. To borrow a phrase from artist and art critic John Berger, we mediate between what is given and what is desired.

The essays in this collection address five groups of mythologies that help to rationalize the present system of social relations: racism, criminal justice, free expression, worker rights, and human rights. They deconstruct what the state and the wielders of monopoly power tell us, in order to seek out what is really going on.

Throughout these essays, I repeat a theme: the law is not what it says, but what it does. What “it does” is so often based on assumptions that time and the tide of events have shown to be false. Karl Marx wrote, “The law shows its a posteriori to the people, as God to his servant Moses.”3 As Anatole France famously wrote: “‘The majestic equality of the laws, which forbid the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets and to steal bread.”

The “law” is itself an ideology, constructed to define, defend, and enforce a system of social relations. Its mythologies are enshrined as precedents. Jonathan Swift wrote in Gulliver’s Travels:

It is a maxim among these lawyers, that whatever hath been done before may legally be done again: and therefore they take special care to record all the decisions formerly made against common justice and the general reason of mankind. These, under the name of precedents, they produce as authorities, to justify the most iniquitous opinions; and the judges never fail of decreeing accordingly.

If we focus only on what “the law” says, we catch ourselves saying that “the law has evolved,” which is like saying that “the market has crashed,” or “the bank has failed,” or “the car did not stop at the red light.” This formulation reifies and mystifies legal rules, and if accepted leads to alienation and disempowerment. The law is not the juristic incarnation of Adam Smith’s “invisible hand.” People operate it. Other people can resist it and change it. And if those people are lawyers steeped in constitutional history and tradition, they have a duty to change it.

To speak of “the law” changing risks mischaracterizing mythology-busting. Several years ago, a lawyer argued in the United States Supreme Court that persons of the same sex have a constitutional right to marry. Justice Scalia asked the lawyer, when did same-sex marriage become a constitutional right? Was it 1789, or when the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified, or when? The lawyer replied that the Court had never thought such a question required answer.

To see how absurd that question was, one might ask rhetorically—as my wife did when she heard the argument and the justice’s question—when did the earth begin to revolve around the sun. Was it when the Pythagoreans proposed that it did, or when Copernicus confirmed it? When did racial segregation in schools become unconstitutional? Was it not until Brown v. Board of Education, or had it always been at odds with the text and spirit of the Fourteenth Amendment? No, busting mythologies brings hitherto disregarded truths to bear upon outworn structures of words and thought.

Busting mythologies is not only the work of lawyers. Lawyers do it because they confront institutions of state and monopoly power in a particular way and within a determined structure. But the struggle for human liberation makes mythology-busting the business of all of us. As the Nigerian poet Wole Soyinka wrote: “The Truth shall set you free? Maybe. But first the Truth must be set free.”

We will not find “Justice” uniquely in the words and work of lawyers, any more than we would find it in the basket under the guillotine. We will find it in human stories and human experience. The struggle for human liberation can be assisted and protected in some significant ways by what lawyers and their clients are able to achieve. Ultimately, people in motion will decide matters.

The essays in this book deal with claims for justice, “rights” if you will. You will find that once mythology is cast aside, the rights we value are not the product of the present system of social relations. Rather, these rights are in tension with, and in contradiction to, that system. Changing the system then becomes the next task.

Twenty-five years ago, I wrote a play titled Haymarket: Whose Name the Few Still Say with Tears.4 I imagined a conversation between Clarence Darrow, who first became involved in human rights defense as he sought a pardon for the surviving defendants of the Haymarket trial,5 and Lucy Parsons, widow of one of the Haymarket defendants who had become a leader of the anarchist movement in the early 1900s.6 In one scene, Darrow and Parsons meet on a Chicago street:

DARROW: Lucy, I’m sorry I’m late. The train from Springfield was delayed. Governor Small has pardoned the Communist Labor defendants.

LUCY PARSONS: Another victory for civil liberty, Clarence. Another supplication to the state.

DARROW: Another victory for the law.

LUCY PARSONS: Wrong! A victory, perhaps, for the lawyers. Your lawyers’ victories, Clarence, are like fireflies. You catch them and put them in a jar. By morning, their light has gone out. And your bugs are dead.

Later in the play, Parsons mocks Darrow:

LUCY PARSONS: Your lawyer’s ego wants you to think you stand at the center of every event by which the world is changed. Your right to stand there is only because some brave soul has risked death or prison in the people’s cause and you are called to defend him—or her. When you put law and lawyers at the center of things, you are only getting in the people’s way, and doing proxy for the image of the law the state wants us to have. The law is a mask that the state puts on when it wants to commit some indecency upon the oppressed.

DARROW: (angry) If I believed that, I would still be a lawyer for the railroad, and not making do with the fees the union can pay. Lucy, the law is a fence built around the people and their rights.

LUCY PARSONS: (kindly) What an image! And you, Clarence, are a fierce old dog, set to bark and warn off intruders.

In that imagined debate between Darrow and Parsons, they are both right. Many of the essays in this book discuss victories won in courts by lawyers on behalf of clients. To imagine that those victories have wrought—or could have wrought—fundamental and lasting social change would be to embrace a disabling and disempowering mythology. We lawyers try cases. We provide outcomes, not solutions.

Lawyers who exaggerate the importance of their professional training may be forgiven. Too much of legal education these days is focused on cases and principles, and does not descend (or ascend, I think) to the study of the human conditions that are at the root of the matter. Most law students have never personally experienced or shared the injustices that their potential clients have faced. They are taught the principles of law and legal analysis. Clinical legal education programs, now a feature of most law school curricula, can play an important role by introducing students to what law “does” as distinct from what it “says.”

Let me try out a metaphor. On the walls of a beautiful ancient Zen temple in Japan are paintings of tigers. I like paintings of tigers. But these tigers do not look like any tiger you or I have ever seen. They are more like house cats done bigger and with stripes, and their expressions are not at all tiger-like.

The reason is that these painters had never seen a tiger. They had read reports from those who had seen tigers. And so it is with those who paint pictures of legal rules that are claimed to be good and proper, but who have never seen or studied or mingled with the people to whom these rules are to be applied. Anyone, including a lawyer, who wants to play a role in the struggle for human liberation had best begin by finding out what is really going on.

In 2014, the cases about the right to marry were pending in courts across the nation. In one such case, the Court of Appeals denied that right, by a vote of 2 to 1. The majority opinion was an excursus into generalities of social policy and the supposed limits of judicial power to address fundamental questions. This is a form of judicial detachment that we will see again in this book. The dissenting judge, Martha Daughtrey, exposed the mythology inherent in the majority opinion:

The author of the majority opinion has drafted what would make an engrossing TED Talk or, possibly, an introductory lecture in Political Philosophy. But as an appellate court decision, it wholly fails to grapple with the relevant constitutional question in this appeal: whether a state’s constitutional prohibition of same-sex marriage violates equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. Instead, the majority sets up a false premise—that the question before us is “who should decide?”—and leads us through a largely irrelevant discourse on democracy and federalism. In point of fact, the real issue before us concerns what is at stake in these six cases for the individual plaintiffs and their children, and what should be done about it.…

In the main, the majority treats both the issues and the litigants here as mere abstractions. Instead of recognizing the plaintiffs as persons, suffering actual harm as a result of being denied the right to marry where they reside or the right to have their valid marriages recognized there, my colleagues view the plaintiffs as social activists who have somehow stumbled into federal court, inadvisably, when they should be out campaigning to win “the hearts and minds” of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee voters to their cause. But these plaintiffs are not political zealots trying to push reform on their fellow citizens; they are committed same-sex couples, many of them heading up de facto families, who want to achieve equal status—de jure status, if you will—with their married neighbors, friends, and coworkers, to be accepted as contributing members of their social and religious communities, and to be welcomed as fully legitimate parents at their children’s schools. They seek to do this by virtue of exercising a civil right that most of us take for granted—the right to marry. Readers who are familiar with the … Seventh Circuit’s opinion in Baskin v. Bogan, 766 F.3d 648, 654 (7th Cir. 2014) (“Formally these cases are about discrimination against the small homosexual minority in the United States. But at a deeper level … they are about the welfare of American children.”), must have said to themselves at various points in the majority opinion, “But what about the children?”

In 2015, the Supreme Court upheld Judge Daughtrey’s position.7