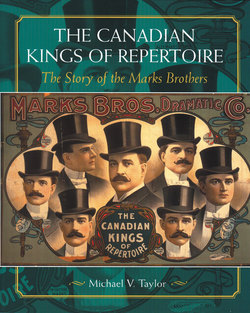

Читать книгу The Canadian Kings of Repertoire - Michael V. Taylor - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1 HOW ARE YOU GOING TO KEEP THEM DOWN ON THE FARM? – 1876 TO 1882

“Listen! Folks! Listen!” So went the ballyhoo of King Kennedy, magician, the Mysterious Hindu from the Bay of Bengal,” as he motioned a small and inattentive crowd to step closer and view first-hand the never-before-seen mysteries of the Orient.

King Kennedy was a lot of things, but a Hindu from the distant shores of Pakistan, he was not. In fact, the only border he ever crossed was between Canada and the United States. He was, in reality, an itinerant showman, and not a very successful one at that, as was evidenced by the apathetic reception he was receiving from the assemblage in the small Eastern Ontario hamlet of Maberly.

Kennedy’s banter reverberated around the village well over one hundred years ago. Like his many contemporaries, he toured the Canadian hinterland during the post-Confederation period, entertaining audiences with card and slight-of-hand tricks, ventriloquism stunts and popular songs.

As the crowd gingerly edged its way closer to the gesticulating “Hindu” on that crisp autumn evening of 1876, a nineteen-year-old youth named Robert William Marks, purveyor of sewing machines and five-octave harmonicas, took stock of the less than enthusiastic gathering and attributed its apathy to the magician’s mediocre performance. But luckily for the “Mysterious Hindu,” Robert Marks (R.W.) recognized the native cleverness of the performer and fixed a conclusion in his mind: that King Kennedy, properly managed, could generate three times the gate receipts. According to popular belief at the conclusion of the evening’s performance, R.W. approached Kennedy with a proposition:

“I own a team of horses and a wagon; you have a tent and a lot of clever bunco. Let’s hitch and take fifty-fifty of the profits.”1

Thirty-six years later, however, R.W. would give a less fictional account of this historic meeting:

“One night, in the company of several other young men I went to the village of Maberly to an entertainment put on by a magician and ventriloquist. The show was all right but the men were evidently travelling in hard luck. After the show I asked them what they would ask for a weeks engagement. They would not sell it out for a week, but offered me half interest in the show at a low price and I took them up. I knew a number of good villages in that locality, and with my father’s democrat and horses I started on the road with the company I made money right from the start, and the next season had control of the company myself.”2

From that day on R.W. never looked back. It was this chance meeting that formed the foundation of the famous Marks Brothers travelling theatrical companies, which, from its humble beginnings of one company in 1876, mushroomed into four independent troupes by the turn of the century. The Marks brothers, born of Irish-Canadian parents in rural Lanark County were seven in all: Robert William, generally known as R.W., Tom, John, Joseph, Alex, McIntyre (usually called Mack) and Ernie. With the exception of John, one by one they left the family farm at Christie Lake, near Perth, Ontario, and “took to the boards.” Their sisters, Nellie (Ellen Jane) and Libby (Olivia Mariah), never appeared on stage and by all accounts never aspired to do so.

Although R.W. had no theatrical experience whatsoever when the glare of kerosene footlights captured his imagination, he did, however, have enough savvy to learn quickly how to please the entertainment-starved populace of the day. When Tom, the second oldest (b.1857) joined R.W.’s fledgling company circa 1879, history records he willingly abandoned his apprenticeship to a local cobbler. However, an article in the October 1, 1926, issue of Maclean’s magazine tells a different story. The author, James A. Cowan, had interviewed Tom at his Christie Lake home earlier that year. According to this article, the aging actor had already had considerable show business experience – experience gained while touring throughout the United States with Buffalo Bill Cody and a number of blackface minstrel shows before joining his brother. It is highly unlikely that this was the case, as extensive research on the subject has failed to uncover any factual information to substantiate this claim. Notwithstanding, Tom’s earlier exploits as recounted by Cowan make interesting reading.

Alex (b. 1867) was the next in line to contract “stage fever.” Without hesitation, he traded his pitchfork for a silver-headed cane and joined his celebrated brothers. Joe (b. 1861) was within six months of becoming an ordained Anglican minister when the lure of the “kerosene circuit” and the charms of a pretty soubrette convinced him his future lay in a different direction. When Ernie, the youngest (b. 1879), added his name to the Marks Brothers playbill, he had already left high school and was apprenticing as a cheesemaker in a small factory on Concession 3 of Bathurst township. But it was not until after the turn of the century that Mack (b. 1871) finally capitulated and donned the top hat, tails and diamonds that distinguished the Marks Brothers from all other troupes in their out-of-door appearance. John, the third oldest (b. 1859) had very little to do with the theatrical exploits of his brothers. He, like his sisters, never appeared on the stage, but it is believed he acted as advance agent on occasion before moving to the western United States in 1886 to seek his fortune in an unrelated line of work.

R.W. and King Kennedy were, at first, content to play the numerous town halls, hotels, fraternity houses and church halls that abounded throughout rural Eastern Ontario. But after several years of performing their mixed bill of music, magic, card tricks, jokes and ventriloquism stunts, and meeting with only limited success, they decided a change of venue might broaden their horizons. Thus, a decision was made to embark on an extended road tour which would have its beginnings in Western Canada.

In the spring of 1879, R.W. and Kennedy began their sojourn to Winnipeg. [According to an article in the Perth Courier of August 27, 1937, Tom left for Winnipeg with R.W. and King Kennedy in 1879. There are differing accounts of when and how Tom Marks joined his brother’s theatrical company.] Getting there would prove to be a monumental task as it would still be another six years before the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway would be completed. Necessity dictated they should make their way to Northern Ontario by horse and buggy where they would catch a westbound train. This slow, but dependable mode of transportation also served an alternative purpose as it allowed the company, such as it was, to play one-night stands in the numerous communities that dotted the route. They were thereby guaranteed a consistent source of income which would enable them to bring their specialized brand of entertainment to the early settlers of the West. In later years, R.W. would recall:

“We drove the team and buggy to Owen Sound and then boarded the ‘Northern Belle’ to Parry Sound, then it was on to Copper Cliff, Manitoulin Island and Port Arthur. I could have vaulted across Winnipeg on any clothespole. It was just a muddy, fresh-rigged town with about 1,500 inhabitants that Easterners thought was a thousand miles northwest of the North Pole and didn’t care if it moved another thousand miles closer.”3

Winnipeg, may not have been quite as rustic as R.W. described it, for, despite his unflattering remarks, the settlement one year later was a hive of activity as the following narrative recounts:

“We saw a broad main street boarded with high wooden sidewalks and rows of shops of every shape and size. Some were rude wooden shanties, others were fine buildings of yellow brick. High over all towered the handsome spire of Knox Church. Several saw and grist mills sent up incessant puffs of white steam into the clear air. The street was full of bustle and life. There were wagons of all descriptions standing before the stores. Long lines of Red River carts were loading with freight for the interior.

“The sidewalks were filled with a miscellaneous crowd of people: – German peasants, French half-breeds, Indians, Scots and English people, looking as they do all the world over. The middle of the street, though there had not been a single drop of rain, was a vast expanse of mud – mud so tenacious that the wheels of the wagons driving through it were almost as large as mill-wheels, and when we dared to cross it, we came out the other side with much difficulty, and feet of elephantine proportions.

“The city of Winnipeg, which eight years ago was nothing more than a cluster of houses about the Hudson’s Bay Company’s fort now contains 7,000 inhabitants.”4

Having reached their destination, R.W. immediately set about finding a suitable location in which the company could “demonstrate their wares.” One was found, but not in the town hall or opera house as might be expected, but in one of the numerous smaller halls that were common place in Western communities. These buildings were usually extensions of local bars and saloons. One of these establishments was the Pride of the West Saloon, which was “proud of its piano, and supported a high class vaudeville.”5 Red River Hall was Winnipeg’s first theatre, built in 1871. The stage , consisting of a platform raised about a foot off the floor, was lighted by oil lamps and heated by several stoves. The only entrance and exit was a narrow plank staircase running transversely across one end of the building on the outside. Other makeshift theatres soon followed: Theatre Royal, Dufferin Hall and the Winnipeg Opera House. When Cool Burgess arrived in 1877, Winnipeg became a regular attraction for professional touring companies.

R.W. never mentioned where the company actually played its first Winnipeg performance. Perhaps it was in the Pride of the West Saloon, but we do know they played for three nights and those burly patrons without ready cash to pay their admission did so with gold dust.

Up until the time of his death in 1936, R.W. maintained their show was the first organized entertainment of its type ever to perform in Winnipeg. The Winnipeg Free Press, as it was then, helped substantiate this claim by declaring, “Hurrah, we’re not in the backwoods anymore, a show has come to town.”6 On reading this excerpt, Winnipeg residents would have, no doubt, recalled other professional touring companies that had performed in the community prior to the arrival of R.W. and Kennedy, performers such as E.A. McDowell and Cool Burgess. When Burgess played the town in 1877, the Free Press, conscious of this significant event, had commented: “The visit of the first professional troupe to this province will long be remembered as an interesting era in the social history of Winnipeg.”7

Regardless of which troupe was first, the “wandering minstrels” from Lanark County, it is said, performed admirably, even though seating arrangements left much to be desired. In order to watch the production in relative comfort, many patrons were forced to sit on beer and nail kegs and rough planking. R.W. never said whether or not the engagement was a financial success, but the following quotation lends one to believe that it was not that lucrative a venture:

“We weren’t looking for money, we wanted experience and we got it.”8

Winnipeg had not only provided R.W. with the experience he had been seeking, but it was also an ideal point from which to embark into the more populated and affluent towns of the American midwest. The only efficient mode of transportation into the Dakota Territories from Manitoba in those days was the “flyer” or flat-boat down the Red River. With their newly-found confidence, R.W. and Kennedy, accompanied by three or four hardy individuals who had signed on to assist the budding troupe, wasted no time in taking to the boats.

Their first, although unscheduled, stop in this new territory was at Grand Forks, North Dakota. No sooner had the “flyer” slipped into the wharf, when the town sheriff, fingering a holstered revolver, made his appearance. After dispensing with the customary greetings and salutations, the peace officer, upon learning of their profession refused to allow the thespians to continue their journey and ordered them ashore. R.W. was at a loss to explain the reason for the lawman’s seemingly hostile attitude, but as it turned out no malice was intended. All that was required of the company in order to continue its trek was to give a performance.

“The townspeople won’t let you go,” stated the lawman.

“But you have no hall,” protested R.W. as he surveyed the settlement from the jetty.

“If you give the order, we’ll fix up an opera house in half an hour,” came the sheriff’s ready reply.9

Realizing the futility of declining this obvious attempt at extortion, R.W. reluctantly consented to give one performance and one performance only. Within minutes of R.W. having declared his intentions, half the able-bodied men in town were scurrying about collecting beer kegs, planks and tables, which were then set-up in a yet unfinished store, and instantly transformed it into an “opry house.” What had initially began as an impromptu entertainment stretched into a three-performance engagement. Yet this was not the first organized entertainment Grand Forks had ever seen, as one might expect considering the circumstances. Several years earlier, residents had attended a production of “Only a Farmer’s Daughter,” and had been incensed at the format because it poked fun at a rural community. The local newspaper announced grimly that no more such offerings would be tolerated.10

Whenever a touring troupe struck town in the American West during the 1880s, cast members risked acquiring a perforated hide, thanks to the antics of pistol-packing cowboys who delighted in shooting out the footlight chimneys. The unofficial mandate of most towns during this period decreed all itinerant companies should be the natural target of the drunken, well-armed cow-puncher. These overt acts of hostility, performed under the guise of “good fun” invariably reduced the house to darkness and chaos within minutes, and proved very disconcerting to the more respectable patrons in the audience. But more importantly, this form of horseplay was eating into R.W.’s profits. Touring troupes were responsible for all property damage incurred during a performance, and this fact alone deemed it necessary to devise a quick and affordable solution to the dilemma.

R.W. was obviously one those rare individuals endowed with the uncanny ability to assess a situation and act accordingly, giving little regard to the consequences. His ultimate solution in solving this problem had a touch of genius about it – simply hire the local ruffians to police each performance, thereby ensuring their continued pacification for the duration of the company’s engagement. Implementing this idea was as simple as the solution itself. R.W. would leave the troupe on the outskirts of town while he made his way to the local saloon. Here he would enquire of those individuals known to delight in the sport of “chimney potting” or any other disruptive activity. Then, with names in hand he would seek them out and, once found, the combination of his ready Irish wit, bawdy conversation and more than a liberal amount of drink, would result in an understanding they were to enter his employ as peacekeepers for the duration of the show.

In theory, this somewhat novel approach should have worked, and to some degree it did. But there were other unforeseen ramifications that would soon make themselves apparent. With solemn conscientiousness these defenders of law and order carried out their appointed task. Ugly and burly, they would patrol the aisles during the performance, swaggering from left to right under the influence of R.W.’s whiskey. Woe betide the man or woman who laughed at the wrong cue or laughed too loud. Within seconds of the outburst, one of the ruffians would appear, tap the miscreant on the shoulder and mumble something about “filling them full of lead.” R.W., the consummate businessman and manager that he was, had succeeded in applying a “band-aid solution” to the problem, but some years later he would reflect upon the wisdom of his actions by saying:

“The gunmen kind’a, spoiled the quiet scenes.”11

R.W.’s imposing stature, for he stood just over six feet and was impressively broad-shouldered, demanded a modicum of respect, and this was generally accorded him in most villages and towns throughout the Dominion and the northern United States. But such was not always the case in the American midwest, where the motto, “God created man, but Samuel Colt made them equal,” was the catchword of the day. Caldwell, Kansas, in the early 1880s could aptly be described as one such typical western town of the period. This was a town where whiskey and bullets went hand in hand and a six-gun did the talking for most men.

A story is told that no sane individual would dare wear a plug topper while strolling about town for fear of the obvious consequences. But R.W. then, and until the time of his death, always wore a silk top hat – a trademark that distinguishes the Marks Brothers from all other troupes in their public appearances. When warned of the impending danger awaiting him should he fail to remove his chapeau, R.W., in typical fashion, threw all caution to the wind and marched down the main street to the Silver Dollar Hotel. Once inside he took note of his surroundings and sat down. But as soon as his feet touched the floor, he detected a solemn footfall behind him. In an instant, a pistol was lodged within inches of his “topper.” Just as quickly the crack of two bullets echoed around the room before they found their way into the opposite wall. Understandably, R.W. was somewhat shaken by this incident, but with poise and dignity befitting royalty, he turned, faced the gunman and said, “Pardner, please take better aim next time.”

With smoking gun in hand, the cowboy glowered above him, stunned by R.W.’s cool and calculated manner. The wrangler in his half-drunken stupor had mistaken the actor for a preacher. When he realized his error, he blurted, “Will ya trade hats?” R.W., caught off-guard by this unusual request, hesitated for a moment. Fortunately he caught the attention of a gesticulating bartender who had taken cover behind a partition when the shooting started, urging him to accept the proposal. Without further ado, R.W. declared, “Done!” In the true spirit of the West the deal was consummated with round after round of drinks. As luck would have it, this incident proved most opportune for R.W as the wrangler was one of the largest ranchers in the area. To show his admiration for the itinerant showman, he ordered a number of his ranch hands to form a guard of honour and escort the Canadian about town. He also declared that each of his employees must purchase at least one ticket for the evening’s performance.12

As early as 1881, R.W. began formulating a long range plan for the company. During his trek through the American West he had encountered a number of troupes who were performing a similar style of entertainment, but in a more polished manner. These companies had included in their repertoire the usual variety players, but augmented the playbill with one and two act melodramas which were well-received by the theatre-going public. R.W. realized that if the company failed to keep pace with the ever-increasing standards demanded by audiences, the troupe would inevitably fall victim to what many considered the showman’s death rattle – mediocrity.

He had no intention of descending into that chasm, an abyss from which few entertainers ever emerged. Instead, he initiated a plan of action that would ensure the company’s continued success. By now, he had recruited his brother Tom to replace King Kennedy (who had left the troupe for parts unknown) and combined their talents with two Kansas soubrettes, Emma Wells and her sister Jennie, who took the stage name of Jennie Ray. For many years, it was generally accepted that a chance meeting in Caldwell led to this union; but in 1932, R.W. refuted this belief:

“In Pittsburgh, in 1882, two ladies were added to the company.”13

The lovely Emma Wells, vocalist and leading lady, joined R.W. and Tom Marks in 1882, along with her sister Jennie Ray, to form the touring company then known as “the Big Four.” The photograph was taken by the W. Bogart Studio of Newmarket, Ontario, date unknown. Perth Museum Collection.

Jennie Ray, pianist and sister of Emma Wells, was the fourth member of the early troupe that would become the Emma Wells Concert Company. She remained with the troupe until about 1890. Perth Museum Collection.

The newly formed troupe specializing in variety was known as “The Big Four.”

In the ensuing years it came as no surprise that their business relationship should blossom into one of a more personal nature. R.W. and Emma Wells remained paramours for sixteen years, while Tom and Jennie Ray ended their rumoured liaison about 1885, prior to his marrying Ella Maude Brokenshire, of Wingham, Ontario. As the company’s reputation grew, R.W. was cognizant that “appearances” had to be maintained, so in keeping with Victorian attitudes of the day, he let it be known that the ladies from Kansas were in fact – his cousins. This ploy was intended to appease the more sensitive and moralistic segment of society who would look upon such an “un-Godly” liaison with utter disdain and condemnation.

Under normal circumstances, this deception would have been unnecessary had the company remained content to play strictly variety. Scattered throughout the West were thousands of communities whose inhabitants were not overly concerned as to the purity and righteousness of their entertainers or their entertainment. But R.W. had the foresight to realize there was a relatively untapped audience waiting in the wings — an audience comprised mainly of women and children who seldom, if ever, had the opportunity to attend a performance given by a travelling company for fear of having their Puritan sensibilities damaged beyond repair. Ultimately, it was this faction of the population that R.W. wanted to reach; their numbers were in the hundreds of thousands if not millions, and common sense dictated even at five cents “a head,” there was a fortune to be made by catering to this, the silent majority, who wanted only to see wholesome, family entertainment. As R.W. noted in a 1921 interview:

“There are two kinds of people we try to draw, the young man and his girl who want to see every show end with a marriage, and the middle-aged, unromantic team of house-keepers who look on marriage as a chestnut and want to see some of the tragedy and clash of fiction. Then, of course, everybody, young and old, or middle-aged, loves a comedy. The comedian’s jest is the great universal tonic. Above everything else the world wants to laugh, and the man who can sell tickets to a laugh is on his way to fortune.”14

In the same interview R.W. outlined some basic show business philosophy:

“The best time to go into a town with a show is immediately after the declaration of a strike. The average workman meets his chum; ‘Bill,’ says he, ‘we’re going to win this strike. ‘Right you are,’ says Bill, ‘and in two weeks they’ll be crawling at our feet.’ ‘let’s go to the show tonight.’ About ten days after a strike begins the first jubilation wears off and, as a show manager, I prefer to be some place else.”15

“The Big Four,” with its expanded repertoire, decided the time had come to embark on a cross-country tour in order to enlarge its growing “sphere of influence.” According to Tom, in a 1921 interview with Maclean’s magazine, the company headlined with great success in most major cities from San Francisco to New York. Along the way they entertained the inhabitants of small-town America, and some communities were so small they could not even lay claim to being a “one-horse” town. But the rough and tumble mining and logging towns offered the company its greatest challenges.

Somewhere along the route the troupe underwent a name change. “The Big Four” had passed into oblivion, and in its place emerged the “Emma Wells Concert Company” The Emma Wells Concert Company was exactly what its name implied, a company that offered the intelligent public a varied and refined entertainment, combining the best of the old favourites with new innovations and melodrama.

R.W. was forever destined to play the straight man, while Tom, a natural comedian, served as comedy lead. Their jokes culled from the pages of old almanacs and similar publications were simple but effective:

R.W: “Can’t understand that hen of mine. Everytime I see her she’s sitting on an axe.”

Tom : “She’s broody, you fool. She’s only trying to hatchet!”

and

Tom: “So you’re a college man, are you?”

R.W.: “Yes indeed. I have studied Latin, Greek, geometry and algebra.”

Tom: “All right, if you’re so smart, let’s hear you say it’s a fine day in algebra.”16

But prior to assuming their on-stage roles, R.W. and Tom had other tasks to perform – equally important; they were obliged to divide between them the duties of doorman and ticket-taker. Emma Wells was also remarkable in her own right. She would soon gain nation-wide fame for her four-voiced vocalisms, which entailed singing in rapid succession, soprano, alto, tenor and bass. As well, she was an accomplished pianist and dancer.

The American logging and mining towns of the 1880s and 1890s would prove to be a financial boon to those adventurous stock companies. Not only did they endure verbal abuse, but more often than not risked personal injury at the hands of whiskey-soaked roughnecks who prided themselves on their ability to disrupt an evening’s performance at the “drop of a hat.” It was a rare occasion indeed, when R.W. and Tom were not called upon to forcibly eject at least one boisterous member of the audience for his unsolicited “stage participation.” In essence, this nightly ritual amounted to “theatrical warfare.” Theirs was a never-ending crusade to ensure peace and quiet, and their subsequent success in maintaining law and order earned them enormous respect.

Their highly efficient method of ejection was technically known as “going over the footlights.” The skill acquired by these two Lanark County farmboys made it a simple process, requiring only a few minutes of a man’s time. Whenever it became apparent that a spectator was a chronic interrupter, one or both of the brothers, accompanied by as many members of the company as was deemed necessary to handle the situation, would leap into the house and whisk the miscreant into the street. With matters well in hand the performance would continue, confident that no further interruptions would be forthcoming that night. Many evening’s while R.W. and Tom were busy with their extra curricular activities, the remaining cast members would continue the production, awaiting the return of the “battling duo.” Upon completion of their task, the two would leap back on stage and resume where they had left off, as if nothing had happened.

Some years later, Tom would say that the Pennsylvania mining towns, Mississippi settlements and the raw Montana communities offered the biggest challenge.17 Whenever the company played these hostile territories, R.W. and Tom literally fought their way through each performance. Yet, this necessary, but regrettable, activity quickly endeared them to the more sedate patrons, who endowed upon them the nickname, “the strongman and the wildcat.” These Lanark County natives were credited at the time, so the literature suggests, with changing the whole complexion of show business in these areas. The rowdy element accounted for a very small percentage of the total population, but its consistent trouble-making had kept respectable citizens away from the theatres. The peace-loving segment of society had no intention of paying for an evening’s entertainment only to become embroiled in a near riot.

“The strongman and the wildcat” squelched these disturbances without mercy, and their reputations were well known all over the continent to both showmen and ruffian alike. During these “blood and thunder” days, they forged their pugilistic reputations in stone and sinew, as more than one aching and bruised heckler would attest after he found himself tossed out on his ear, accompanied by a roar of approval from the remaining patrons.

Although most incidents lasted only a matter of minutes, if that, there was one occasion, when this was not the case. The setting was in one of those crude and inhospitable Pennsylvania mining towns that had been incorporated on the 1893-94 circuit. The hall in which the Emma Wells Concert Company was to give a performance was situated on the second floor of what can best be described as a rudimentary town hall. Just moments before the opening curtain, a handful of vociferous miners clamoured up the stairs where they were met by R.W. and Tom, engaged in their secondary occupation of selling and collecting tickets. The miners, revelling in their alcoholic euphoria, made it quite clear they were not about to pay admission to a hall which they claimed to have rented for the evening. It soon became apparent that no amount of pacification on the part of the Marks brothers was going to prevent the confrontation that both parties knew was imminent.

Threats and intimidation were no strangers to these showmen who simply delivered an ultimatum – pay the going rate of admission or leave the premises; the latter option would be accomplished by force if necessary. Preferring to drive home their point with actions rather than words, these “hewers of stone” opted to stand and fight. So, with their usual aplomb, R.W. and Tom went to work and, in doing so, gave an admirable account of themselves by routing the would-be gatecrashers and inflicting upon them grievous injuries. Sore and bloodied, the miners, eager to pacify their bruised and battered egos found solace in the contents of a nearby slag heap. After arming themselves with a quantity of rocks, they returned to the hall determined to seek revenge on the thespians.

During the final act of “The Two Orphans,” the house suddenly erupted in chaos as a barrage of stones and vindictives invaded the solemnity of the “inner sanctum.” Broken glass flew in every direction as frightened spectators dove for cover. The barrage continued throughout the night, pausing only long enough to allow the patrons to go home; but under no circumstances were any cast members allowed to leave. The siege finally came to an end at daybreak when the beleaguered miners cooled their enthusiasm for revenge. One by one they discarded their ammunition and dispersed without any apparent satisfaction, having caused the company nothing more than a slight inconvenience and the loss of a few hours sleep.

Thomas and Margaret (Farrell) Marks, parents of the seven Marks brothers, as shown in an 1895 family photo. Perth Museum Collection.