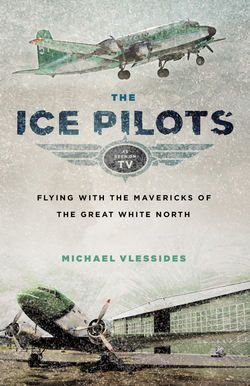

Читать книгу The Ice Pilots - Michael Vlessides - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ARRIVALS

ОглавлениеFrostbite wasn’t the only thing going through my head as I boarded the Bombardier Dash 8 scheduled to take me from the relatively balmy climes of Calgary, Alberta, to Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, one clear mid-January morning. Truth be told, though, it ranked high in the panoply of thoughts swirling through my mind: Will Buffalo Joe like me? Does a wind chill of –42° feel any different to a forty-six-year-old body than it does to a thirty-year-old one? Just how safe is a seventy-year-old plane, anyway?

Those questions, and a hundred others, were bound to be answered during the first of what would prove to be many trips to Yellowknife in the coming months. In the meantime, though, I settled into the modern—if not particularly spacious—comfort of the plane, one of the most popular regional turboprop airplanes in the world.

For good reason. The Dash 8 is a picture of efficiency: depending on the model, the plane will carry anywhere from thirty-seven to eighty passengers at speeds that can eclipse five hundred kilometres (three hundred miles) an hour with relatively little fuel consumption. The interior of the cabin also speaks to modern aviation’s obsession with function over comfort. Somehow we managed to park two humans on either side of an aisle large enough to accommodate the flight attendants’ snack tray in a fuselage that boasted a diameter of less than three metres (ten feet). In other words, if your seatmate feasted upon a three-bean burrito for breakfast, you’d know about it.

Nevertheless, the seat cushion into which my nether regions nestled was soft and inviting, and the overhead lighting cast a warm glow throughout the aircraft that mimicked the brightening sky to the east. The plane’s highly insulated plastic shell deadened the sound of its two turboprop engines. We may have been squeezed in like suitcases on a luggage cart, but we were warm, cozy, and about to cover more than 1,200 kilometres (745 miles) in about two hours.

As the plane lifted off, Calgary’s winter landscape began to fall away. The city faded into a prairie patchwork of golden brown and white, dissected into neat squares by the innumerable roads that keep people and commerce flowing along the southern edge of midwestern Canada. Soon we climbed through the ceiling of clouds, and the world below us melted away. All was calm in the upper reaches of the troposphere.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. As we begin our final descent into Yellowknife...”

I awoke with a start to the pilot’s message; the flight had lulled me into a deep sleep as it hurtled across northern skies. And as my eyes adjusted to the light around me and I gazed through the window, I could tell we weren’t in Kansas anymore, Toto.

One of the largest wildernesses on Earth, the Northwest Territories is the raw and often-severe land in which the ice pilots ply their trade. Extreme weather conditions have claimed the lives of many pilots over the years.

The checkerboard of the prairie below had been replaced by something more primal. The golden landscape had given way to two colours that wrestled for dominance: charcoal grey and white. The grey occasionally won the battle, as masses of stunted, hardscrabble spruce trees huddled together, forming broad patches of forest in a great, untamed wilderness. It didn’t take a geographer to recognize that the leaden curves of the forest were mere accents on a backdrop of white.

There was a lot of snow down there. This came as no surprise to me, given that I had spent several years of my life criss-crossing the Arctic, from Fort McPherson in the west to Baffin Island in the east. Snow is a part of life in communities that pepper the subarctic and Arctic regions of the world, regardless of the season. What struck me on this flyover, though, was just how much water was sitting underneath all that snow. In every direction, as far as the eye could see, the landscape was peppered with white blots of varying size and shape, gleaming in the cold winter sun, each indicating yet another body of water, from long-forgotten ponds to vast lakes covering thousands of square kilometres.

It occurred to me that, other than the primal landscape of white and grey, there wasn’t much else going on down there: no herds of caribou loping gracefully across the frozen land, no eagles soaring over the rocky outcrops in search of prey. Hell, I couldn’t even spot a road.

It wasn’t until we were descending to within spitting distance of our destination that the trappings of “civilization” began to appear. Snowmobile trails snaked through the forest, bursting onto frozen lakes, where they broadened and braided, only to constrict again on the far side, where they once again plunged into the forest cover. We drew closer, and a road (singular: one road) appeared, though from that height it wasn’t much more than a grey stripe stretched across the land below.

If anything, the snow served as an acute reminder of my destination. With a population that fluctuates around twenty thousand, Yellowknife is the capital city of the Northwest Territories (it’s also the only city in the Northwest Territories), a place where old and new, traditional and cosmopolitan, blue collar and white collar, rough and refined, Native and non-Native, all coexist fairly peacefully.

The city is located some 512 kilometres (318 miles) south of the Arctic Circle, and bears the dubious distinction of being the coldest city in Canada. According to Natural Resources Canada, Yellowknife’s average nighttime temperature between December and February is a balmy –29.9°C (–21.8°F). Average. That means that for each day warmer than –29.9°C, there’s one colder too. Yellowknife’s mean annual temperature is –5.4°C (22.3°F), a figure even more astoundingly cold once you figure that the city also has the sunniest summers in Canada, with June, July, and August racking up a total of 1,037 hours (that’s forty-three complete days) of sun each year. It’s been estimated that an average Yellowknife winter comprises 191 days, or more than six months.

Yet by the grace of some omnipotent being who realized that my ability to withstand significant stretches of flesh-freezing temperatures had diminished in the years since I left the North, the immediate forecast was on the warmer side of things, relatively speaking. Overnight lows would touch –30°C (–22°F), but daytime highs might actually climb above –10°C (14°F) once or twice. I wasn’t breaking out the sunscreen just yet, but I was grateful nonetheless.

If that doesn’t seem tropical to you, consider the poor bastards who called Yellowknife home in the winter of 2008. At the end of that January, a cold weather system gripped the North like a vise, making people wonder if this might be the time to consider a move to Vostok, Antarctica, which holds the world record for coldest temperature ever recorded on Earth: –89.2°C(–128.6°F), in 1983. For nine straight days, Yellowknife recorded temperatures below –40°, with wind chills regularly exceeding –50°C (–58°F). The city operated in the hushed haze of a persistent ice fog, a phenomenon that occurs when the water molecules in the air freeze and hang suspended like a ghostly veil.

Entire neighbourhoods were obscured. Mail delivery came to a grinding halt. Schools closed to ensure the safety of students and staff.

It’s not like I haven’t seen my share of –40°, though. Like many who call this eclectic place home, I came to the North by a rather unconventional route. Back in the early 1990s, I was happily ensconced in what I then thought was the dream job: working on Park Avenue in New York City, in the Commissioner’s Office of Major League Baseball. Several years earlier, armed with a journalism degree from New York University, I had peppered nearly every sports team on the east coast of the United States with letters seeking employment in their public relations departments. Most chose not to reply at all; those that did all said the same thing: thanks but no thanks. All but one, that is.

Major League Baseball informed me that there were currently no jobs available at the office, but I might be interested in applying for their Executive Development Program, started a few years earlier by new commissioner Peter Ueberroth, who wanted to bring young, eager, and talented executives to the industry. One or two recent university graduates were selected every year from a pool of several hundred applicants. Should I be lucky enough to land the position, I would have the rare opportunity to work in almost every department of the Commissioner’s Office, from legal to broadcasting, licensing to player relations, learning everything there is to know about the business side of the game. After about a year, the “executive trainee” would have the opportunity to land a full-time position in the industry, either with a major league club, a minor league club, or one of the various departments in the Commissioner’s Office itself. Realizing my chances were exceedingly slim and with nothing to lose, I set to the application form with a vigor I hadn’t felt since writing my final term paper for a senior NYU course called “Human Sexual Love.”

I somehow made it through the initial set of interviews, and was shocked to learn I had been selected as one of the finalists. At that point, I realized I was no longer a dark horse in the proceedings and had a legitimate shot at actually getting the job. It was time to break out the big guns. Donning my finest brown wool suit, baby-blue shirt, pink tie, and burgundy wingtips, I headed to the Major League Baseball offices at 350 Park Avenue for my final interview.

The place reeked of tradition, of cool, of a yeah-we-know-we’re-badass-but-we-like-to-play-it-casual-nonetheless attitude. I desperately wanted to be a part of it. Black and white photographs of famous players lined the modest walls. I tried to identify each one in turn, just in case the interview included a quiz: Ty Cobb. Rogers Hornsby. The Christian Gentleman, Christy Mathewson. Babe Ruth. Yup, I was ready.

As I walked into the conference room—the first one I had ever seen in my life—I likely let out an audible gasp. I was confronted by a cohort of nine Major League Baseball executives sitting around a giant oak table.

Nerves notwithstanding, I must have done something right, because within a week I got the call: I was going to the majors! With tears of joy running down my face, I called my parents, Traude and Gus, who had immigrated to the United States from Germany and Greece after World War II in search of a better life. I clearly remember telling them that I had just gotten the job that I would have for the rest of my life. “In forty years,” I said, “they can give me a gold watch, pat me on the back, and show me the door. I’ll be the happiest guy who’s ever lived.”

How wrong I was.

Only a few years later, seeds of discontent began to sprout somewhere deep inside me. As thrilling as baseball was (how many other people do you know who were inside Candlestick Park when the earthquake struck before Game Three of the 1989 World Series?), I started to want something more out of life. The shallowness of my existence was becoming obvious.

I would stand in front of the mirror every morning, wrap my tie into a neat half-Windsor and wonder which client I would have to pretend to like that day. As I began to consider more deeply my place in the universe, I realized I was not cut from the Egyptian broadcloth of Park Avenue. If life held any more great secrets for me, I guessed they would not be found in the hallowed halls of Major League Baseball.

Happy moments such as this one became more and more frequent as the months went by, but that didn’t mean I was immune to the occasional icy glare from Buffalo Joe.

I ended up quitting Major League Baseball and signing on as a volunteer with a small Canadian organization called Frontiers Foundation, which works to this day to provide—among other things—affordable housing in Canada’s aboriginal communities. My responsibilities would be simple, yet profound: renovate and/or build houses for some of North America’s most disadvantaged people. As altruistic as I felt, I was encouraged by Frontiers’ out clause: the minimum commitment was only two months. If I arrived at my posting at some as-yet-unknown hamlet in the middle of Canadian nowhere and realized I had made the biggest mistake of my life, I could always go back to 350 Park Avenue on my hands and knees and beg for my job back.

I didn’t need to. For the first time in my life, I was in a completely foreign environment, living with a group of volunteers from around the globe, working outside at a job for which I had no training, no obvious skills. The learning curve—both on the social and professional scales—was high. Not a day went by that I didn’t learn something about myself, the world, home construction, or the Native people who called these places home. I loved it.

And so the two-month-minimum commitment window came and went, and I continued doing what felt like the most important work I had ever done. For six months, I bounced around several communities northwest of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. If the names Goulais River, Gros-Cap, and Batchawana Bay mean anything to you, you’re a better student of geography than I was at the time. And if I thought the challenges of working outside through the Canadian autumn and early winter were tough, I had a lot to learn.

After a brief trip back to New York for Christmas, I was sent out for my second volunteer posting, one that would test my ability to withstand the rigours of weather like I had never before imagined. I was off to Fort McPherson, Northwest Territories, a community of some eight hundred people—primarily aboriginal Canadians, the Tetl’it Gwich’in—that sits about a hundred kilometres (sixty miles) north of the Arctic Circle.

In six months at Fort McPherson I learned more about life and love than I ever had in New York. Here were a people who by most modern-day measures had virtually nothing, but still knew how to appreciate the small treasures of their everyday existence like few people I had met before. If the Northern Lights appeared in the sky, people would stop you on the street to talk about it. When spring came, you would only need to bump into somebody at the grocery store and they would start regaling you with stories of the black ducks they had seen flying over the river earlier that morning. I was pulled into the methodical, comfortable flow of life north of 60, where drinking tea and eating bannock and dried caribou meat were enough to constitute a social event, and a damn good one at that.

Sure, there were problems in Fort McPherson, problems I would soon learn are common throughout aboriginal communities the world over. Alcohol abuse was rampant. There was nothing strange about encountering somebody fall-down drunk on the town’s hard-packed dirt roads at any time of the day or night, regardless of the season. Suicide, glue-sniffing, spousal abuse, child abuse, arson, and petty burglary wove a tragic thread through the fabric of life in Fort McPherson. One of my favourite people in town was Robert Zheh (not his real name), who quite literally bore the scars of his discontent as a youth. Half of Robert’s face was horribly disfigured, the result of a botched suicide attempt many years earlier. And yet, for all that, I fell in love with the place—and its often brutal weather.

And while the thought of working outside in temperatures that routinely sank below –30°C (–22°F) might have made for many sleepless nights back in my Greenwich Village apartment, I was amazed at how well my body became inured to the arctic environment. Maybe it had to do with the fact that my fellow volunteers and I were all in our early- to mid-twenties, but we threw ourselves into our pro bono work with nary a thought about our well-being. Hammering a nail at –30°C (–22°F) is a painfully drawn-out process (we didn’t have the luxury of air nailers), but the mere fact that we were out there, standing on ladders and dangling ourselves off rooftops in cold that most people would otherwise describe as ungodly, was a feat unto itself.

And as the days got longer and the weather began to warm ever so slightly, we appreciated every ray of sunlight that shone on our ghostly white bodies. I distinctly remember working outside in only a shirt and sweatshirt one brilliantly sunny spring afternoon. The temperature was –20°C (–4°F).

As the Dash 8 touched down on the tarmac of the Yellowknife Airport, I wondered if my body could handle the rigours of cold the way it once did. It’s not like I live in a balmy climate these days; the Rocky Mountain town of Canmore, Alberta, is known for its long, snowy winters. But sitting at a desk in the climate-controlled comfort of my home office is a far cry from pounding nails at thirty below. Frankly, I didn’t know how much I could hack it anymore.

The walk from the plane to the terminal building was enough to foment my weather fears into a frenzy. The flight attendant was merciful enough not to share the temperature on landing, but it was freakin’ cold, and the wind howled across the runway, whipping the fine layer of snow on the tarmac into fanciful whirligigs. It managed to find its way into every nook and cranny of my clothing, poking intrusively at my flesh with icy fingers. At least, I told myself, the Buffalo Airways hangar will be heated.

A couple of text messages later and I was waiting for none other than Mikey McBryan, general manager and heir apparent to the Buffalo empire, to pick me up. In the interim, I had time to ponder what Mikey might be like in person. Truth be told, I felt like I already knew him, the result of crash-coursing as many episodes of Ice Pilots NWT as possible before arriving. From what I could tell, Mikey is an enigma. He is clearly a savvy businessman and the driving force behind Buffalo’s emergence onto the world stage as a TV phenomenon. But at the same time, I couldn’t help but feel that he’s, well, a bit of a frat boy.

And if I expected Mikey to show up at the airport in a late-model sports car befitting his status as a small-time celebrity, I was dead wrong. Instead, a ramshackle white van—resplendently bedecked with the Buffalo Airways logo—rumbled to a stop in front of the terminal. Mikey lumbered out, wearing what I would come to realize may be his only uniform: faded jeans, Buffalo Airways hoodie, and signature ball cap. In fact, in all the time I spent with Mikey in the subsequent months, I don’t think I ever saw him without his ball cap. I never worked up the nerve to check the validity of this theory, but I think he may even sleep with the thing plastered to his head.

Round-faced and chubby, Mikey greeted me with a genuine, friendly air that immediately won me over. From what I could tell, this was a man with absolutely no pretense whatsoever, despite his new-found popularity. He does not try to be anything other than exactly what he is: a straight-shooting, endearing, insightful, forward-thinking, dedicated, hardworking guy who loves women almost as much he loves beer. And while Mikey McBryan demands a lot from himself when it comes to work, he does not (unlike his father) project those same demands onto those around him.

It didn’t take long before I felt like we were old friends.

“Hey, Mike,” he said as he walked into the terminal, greeting me like we had done this a thousand times before.

“Mikey!” I cried, perhaps a little too eagerly, considering that this was, after all, our first time meeting face to face.

“Let’s go to the hangar,” he said, shouldering my heavy, green duffel bag, jam-packed with as much arctic survival gear as I could resurrect from long-ignored boxes in a corner of my basement. The hangar, I soon realized, is Mikey’s home away from home. Actually, scratch that. If the number of hours spent in a place—including sleeping hours—count for anything, then the hangar is Mikey’s home, period. His house, perched on the shore of Great Slave Lake’s Back Bay, is his home away from home.

On the short drive from the airport to the Buffalo hangar, Mikey gave me the lay of the land, Buffalo style. Buffalo Airways started operations back in May 1970, when his father, Buffalo Joe McBryan, bought the operating licence from a man named Bob Gauchie. Since those humble beginnings with only two planes—a Noorduyn Norseman and a Cessna 185—Buffalo Joe and his family have built a unique empire of more than fifty planes, most of which flew during World War II. Instead of buying the latest and greatest aircraft money can buy, Joe McBryan is one hundred percent retro.

As Mikey has been known to say: “Forty years ago, Joe was one of hundreds of people flying these airplanes. Then he woke up one day to find out he was one of the last ones doing it.”

It’s easy to ask why Joe insists on using seventy-year-old planes, and I believe the answer is twofold. First of all, Joe is a collector of old things. “Vintage things,” Mikey corrected me. Right—vintage things. The guy loves vintage cars, old signs, retro hairstyles, and vintage planes. Reason number two: it makes financial sense. Old planes—though increasingly difficult to find and maintain due to a dwindling supply of parts and experienced mechanics—are cheap. Buffalo can pay off a DC-3 in a couple months of hard work, something few airlines can boast when they lay out tens of millions of dollars for a new jet.

Yet for all of our talk about Buffalo the company, most of our conversation centred on Buffalo Joe, captain and president of the airline. As we talked, I got a sneaking suspicion that Mikey was trying to prepare me for something, something unspoken that lay between us on the floor of the rattling van, like a polar bear waiting to pounce on a seal. I ignored it and tried to focus on what Mikey was saying so I could be as prepared as possible to meet Joe in a few minutes’ time.

“He’s always a stress case, always running around and micromanaging one aspect of the business or another,” Mikey said of his father, a man whose legend in the Canadian North has grown to untold proportions thanks to the success of Ice Pilots NWT.

“He thrives on stress, eats it for breakfast, lunch, dinner. And anything going on right now—from a garbage can overflowing in the hangar to whether or not the lights in the bathroom should be left on—he’s worried about it. And he picks it; he picks whatever he wants to stress out about that day.”

“Doesn’t seem like a particularly healthy lifestyle,” I threw in.

“Yeah, but it keeps him going,” he said. “Look at the guy. He’s thin and healthy, but he survives on junk food and adrenaline. He lives like a sixteen-year-old would live, and he hasn’t grown out of it.”

If anything, Mikey said, my biggest challenge would be to slow his father down long enough to get him to talk to me. “That’s why there’s hardly anything written about him; he’s as elusive as Bigfoot,” Mikey said. “How many videos of Bigfoot are there?”

The key is to get to Joe on the weekends, which he spends in Yellowknife with Mikey, instead of at the Monday–Friday home he shares in Hay River with his wife, Sharon. On those days, when the whirl of business has slowed to a manageable level, Joe is at his most relaxed, and therefore, most talkative.

Still, if the stories I’d heard about Joe are true—not to mention the way he’d been portrayed on Ice Pilots—he wouldn’t be inviting me to dinner anytime soon. Even when I lived in remote Arctic communities thousands of kilometres from Yellowknife, people talked about Buffalo Airways and its nefarious founder. Joe was the kind of guy you wanted on your side if you needed a job done—and done now. Hang out socially with the guy? Maybe not. There are stories of new recruits arriving at the hangar on a Friday and leaving for home Sunday morning. Either the TV show has managed to capture every one of Joe’s temperamental outbursts, or they happen with alarming regularity.

Still, I was cautiously confident as we pulled up to the Buffalo hangar. I’d met—and cracked—many tough nuts in my day, so Joe McBryan should be no problem at all. I’d regale him with a few stories about my days in the Arctic to win him over, throw in a bit of the ol’ Vlessides charm, and soon we’d be shooting the shit like we’d been friends forever. He was already on board with the idea of the book, so it was just a matter of getting him to like me. Piece of cake!

Purchased from legendary aviator Max Ward, the Buffalo Airways hangar boasts a concrete floor six feet thick, perfect for withstanding the weight of the aircraft and Yellowknife’s mercurial weather. The hangar houses several aircraft at one time.

As if on cue, I literally bumped into Joe as we walked through the inconspicuous green metal door that opens into the inner sanctum of the Buffalo Airways hangar. I had no trouble recognizing him. His brown hair was slicked back into a neo-pompadour and showed nary a sign of grey despite the fact that he was approaching seventy. His face was not as wrinkled as I thought it would be, his teeth surprisingly white. His clothes were unassuming and spoke to the casual places he’s called home his entire life: dark jeans and a flannel shirt, a red plaid flannel lumberjack jacket on top. He wore his watch backwards on his right wrist.

As Mikey introduced us, I sensed trepidation in my guide’s voice. “Dad, this is Mike. He’s the guy writing the book.”

“Book...” Joe growled, eyeing me suspiciously. “What book?”

Uh-oh.

Mikey’s phone rang and he turned away, now deep in conversation with pilot Devan Brooks.

Joe’s suspicious look bore holes into my skull, out the other side, and through the fuselage of the DC-3 lurking behind me. “I never agreed to no fuckin’ book.”

Oh boy.

I was drowning, my hands stretched helplessly toward the disappearing surface above. The light was fading, my watery grave becoming darker.

Joe broke the silence as I tried to mumble something intelligible.

“Do you have an aviation background?” he asked.

“Well, not really. But I have flown a bunch of times, if that counts for anyth—”

“Then it’s gonna be tough writing that book,” he cut me off. “I’d strongly reconsider it if I were you. I don’t have time to educate people, especially non-aviation people.”

“Actually, this book is not really going to be a technical manual, but more of a story about—”

“You go in that office of mine, and every book on the shelf is an aviation book,” he continued over me. “I read a lot of books to see how accurate they are and how they spread the credit and the blame around. And every one of them is a piece of shit. I buy the books only for time, places, and data.”

Mikey must have seen the beads of sweating forming on my brow, because he finally ended his phone conversation and turned back to throw me a life preserver. Joe took no notice.

“I’m very busy right now,” he continued, “and there aren’t a lot of people helping me. They’re finding me a lot of problems to solve because they can’t handle them themselves. So I’m not really in the best mood to be writing a book.”

Mikey joined me in mumbling and fumbling, trying to explain things to Joe. “It’s really about timing,” Mikey said. Joe had turned on his heels and was heading for the far side of the hangar. Clearly, he’d had enough of our conversation. “Just think about it!” Mikey called after him.

An uneasy silence hung between us as we watched Joe march away. “That went well,” Mikey said. “Better than I thought, actually.”