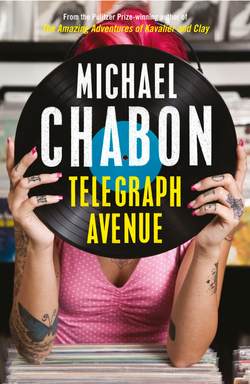

Читать книгу Telegraph Avenue - Michael Chabon, Michael Chabon - Страница 6

ОглавлениеI

Dream of Cream

A white boy rode flatfoot on a skateboard, towed along, hand to shoulder, by a black boy pedaling a brakeless fixed-gear bike. Dark August morning, deep in the Flatlands. Hiss of tires. Granular unraveling of skateboard wheels against asphalt. Summertime Berkeley giving off her old-lady smell, nine different styles of jasmine and a squirt of he-cat.

The black boy raised up, let go of the handlebars. The white boy uncoupled the cars of their little train. Crossing his arms, the black boy gripped his T-shirt at the hem and scissored it over his head. He lingered inside the shirt, in no kind of hurry, as they rolled toward the next pool of ebbing streetlight. In a moment, maybe, the black boy would tug the T-shirt the rest of the way off and fly it like a banner from his back pocket. The white boy would kick, push, and reach out, feeling for the spark of bare brown skin against his palm. But for now the kid on the skateboard just coasted along behind the blind daredevil, drafting.

Moonfaced, mountainous, moderately stoned, Archy Stallings manned the front counter of Brokeland Records, holding a random baby, wearing a tan corduroy suit over a pumpkin-bright turtleneck that reinforced his noted yet not disadvantageous resemblance to Gamera, the giant mutant flying tortoise of Japanese cinema. He had the kid tucked up under his left arm as, with his free right hand, he worked through the eighth of fifteen crates from the Benezra estate, the records in crate number 8 favoring, like Archy, the belly meat of jazz, salty and well marbled with funk. Electric Byrd (Blue Note, 1970). Johnny Hammond. Melvin Sparks’s first two solo albums. Charles Kynard, Wa-Tu-Wa-Zui (Prestige, 1971). As he inventoried the lot, Archy listened, at times screwing up his eyes, to the dead man’s minty quadrophonic pressing of Airto’s Fingers (CTI, 1972) played through the store’s trusty Quadaptor, a sweet gizmo that had been hand-dived from a Dumpster by Nat Jaffe and refurbished by Archy, a former army helicopter electrician holding 37.5 percent—last time he’d bothered to check—of a bachelor’s in electrical engineering from SF State.

The science of cataloging one-handed: Pluck a record from the crate, tease the paper sleeve out of the jacket. Sneak your fingers into the sleeve. Waiter the platter out with your fingertips touching nothing but label. Angle the disc to the morning light pouring through the plate window. That all-revealing, even-toned East Bay light, keen and forgiving, always ready to tell you the truth about a record’s condition. (Though Nat Jaffe claimed it was not the light but the window, a big solid plate of Pittsburgh glass vaccinated against all forms of bullshit during the period of sixty-odd years when the space currently housing Brokeland Records had been known as Spencer’s Barbershop.)

Archy swayed, eyes closed, grooving on the heft of the baby, on the smell of grease coming off of Ringo Thielmann’s bass line, on the memory of the upraised eyes of Elsabet Getachew as she gave him head yesterday in the private dining room of the Queen of Sheba Ethiopian restaurant. Recollecting the catenary arch of her upper lip, the tip of her tongue going addis ababa along the E string of his dick. Swaying, grooving, feeling on that Saturday morning, just before the boots of the neighborhood tracked bad news through his front door, like he could carry on that way all day, forever.

“Poor Bob Benezra,” Archy said to the random baby. “I did not know him, but I feel sorry for him, leaving all these beautiful records. That’s how come I have to be an atheist, right there, Rolando, seeing all this fine vinyl the poor man had to leave behind.” The baby not too young to start knowing the ledge, the cold truth, the life-and-death facts of it all. “What kind of heaven is that, you can’t have your records?”

The baby, understanding perhaps that it was purely rhetorical, made no attempt to answer this question.

Nat Jaffe showed up for work under a cloud, like he did maybe five times out of eleven or, be generous, call it four out of every nine. His bad mood a space helmet lowered over his head, poor Nat trapped inside with no way to know whether the atmosphere was breathable, no gauge to tell him when his air supply would run out. He rolled back the deadbolt, keys banging against door, working one-handed himself, because of a crate of records he had crooked up under his left arm. Nat bulled in with his head down, humming low to himself; humming the interesting chord changes to an otherwise lame-ass contemporary pop song; humming an angry letter to the slovenly landlord of the nail salon two blocks up, or to the editor of the Oakland Tribune whose letters page his anger often adorned; humming the first fragments of a new theory of the interrelationship between the bossa nova and the nouvelle vague; humming even when he wasn’t making a sound, even when he was asleep, some wire deep in the bones of Nathaniel Jaffe always resounding.

He closed the door, locked it from the inside, set the crate on the counter, and hung his gray-on-charcoal pin-striped fedora from one of nine double-branched steel hooks that also dated from the days of Spencer’s Barbershop. He ran a finger through his dark hair, kinked tighter than Archy’s, thinning at the hairline. He turned, straightening his necktie—hepcat-wide, black with silver flecks—taking note of the state of box 8. Working his head around on the neck joints a few times as if in that creak of bones and tension lay hope of release from whatever was causing him to hum.

He walked to the back of the store and disappeared through the beaded curtain, laboriously painted by Nat’s son, Julie, with the image of Miles Davis done up as a Mexican saint, St. Miles’s suffering heart exposed, tangled with a razor wire of thorns. Not a perfect likeness, to be sure, looking to Archy more like Mookie Wilson, but it could not be easy to paint a portrait of somebody across a thousand half-inch beads, and few besides Julius Jaffe would ever contemplate doing it, let alone give it a try. A minute later Archy heard the toilet flush, followed by a spasm of angry coughing, and then Julie’s father came back out to the front of the store, ready to burn another day.

“Whose baby is that?” he said.

“What baby?” said Archy.

Nat unbolted the front door and spun the sign to inform the world that Brokeland was open for business. He gave his skull another tour of the top of his spinal column, hummed some more, coughed again. Turned to his partner, looking almost radiant with malice. “We’re totally fucked,” he said.

“Statistically, that’s indeed likely,” Archy said. “In this case, how so?”

“I just came from Singletary.”

Their landlord, Mr. Garnet Singletary, the King of Bling, sold grilles and gold finger rings, rope by the yard, three doors up from Brokeland. He owned the whole block, plus a dozen or more other properties spread across West Oakland. Retail, commercial. Singletary was an information whale, plying his migratory route through the neighborhood, taking in all the gossip, straining it for nutrients through his tireless baleen. He had never once turned loose a dollar to frolic among the record bins at Brokeland, but he was a regular customer nonetheless, stopping by every couple of days just to audit. To monitor the balance of truth and bullshit in the local flow.

“Yeah?” Archy said. “What’d Singletary have to say?”

“He said we’re fucked. Seriously, why are you holding a baby?”

Archy looked down at Rolando English, a rusty young man with a sweet mouth and soft brown ringlety curls all sweaty and stuck to the side of his head, stuffed into a blue onesie, then wrapped in a yellow cotton blanket. Archy hefted Rolando English and heard a satisfying slosh from inside. Rolando English’s mother, Aisha, was a daughter of the King of Bling. Archy had offered to take Rolando off Aisha’s hands for the morning, maybe pick up a few items the baby required, and so forth. Archy’s wife was expecting their first child, and it was Archy’s notion that, given the imminence of paternity, he might get in some practice before the first of October, their due date, maybe ease the shock of finding himself, at the age of thirty-six, a practicing father. So he and Rolando had made an excursion up to Walgreens, Archy not at all minding the walk on such a fine August morning. Archy dropped thirty dollars of Aisha’s money on diapers, wipes, formula, bottles, and a package of Nuk nipples—Aisha gave him a list—then sat down right there on the bus bench in front of the Walgreens, where he and Rolando English changed themselves some foul-smelling diaper, had a little snack, Archy working his way through a bag of glazed holes from the United Federation of Donuts, Rolando English obliged to content himself with a pony of Gerber Good Start.

“This here’s Rolando,” Archy said. “I borrowed him from Aisha English. So far he doesn’t do too much, but he’s cute. Now, Nat, I gather from one or two of your previous statements that we are fucked in some manner.”

“I ran into Singletary.”

“And he gave you some insight.”

Nat spun the crate of records he had carried in with him, maybe thirty-five, forty discs in a Chiquita crate, started idly flipping through them. At first Archy assumed Nat was bringing them in from home, items from his own collection he wanted to sell, or records he had taken home for closer study, the boundaries among the owners’ respective private stocks and the store’s inventory being maintained with a careless exactitude. Archy saw that it was all just volunteers. A Juice Newton record, a bad, late Commodores record, a Care Bears Christmas record. Trash, curb fruit, the bitter residue of a yard sale. Orphaned record libraries called out constantly to the partners from wherever fate had abandoned them, emitting a distress signal only Nat and Archy could hear. “The man could go to Antarctica,” Aviva Roth-Jaffe once said of her husband, “and come back with a box of wax 78s.” Now, hopeless and hopeful, Nat sifted through this latest find, each disc potentially something great, though the chances of that outcome diminished by a factor of ten with each decrease in the randomness of the bad taste of whoever had tossed them out.

“‘Andy Gibb,’” Nat said, not even bothering to freight the words with contempt, just slipping ghosts of quotation marks around the name as if it were a known alias. He pulled out a copy of After Dark (RSO, 1980) and held it up for Rolando English’s inspection. “You like Andy Gibb, Rolando?”

Rolando English seemed to regard the last album released by the youngest Gibb brother with greater open-mindedness than his interlocutor.

“I’ll go along with you on the cuteness,” Nat said, his tone implying that he would go no further than that, like he and Archy had been having an argument, which, as far as Archy could remember, they had not. “Give him.”

Archy passed the baby to Nat, feeling the cramp in his shoulder only after he had let go. Nat encircled the baby under the arms with both hands and lifted him, going face-to-face, Rolando English doing a fine job of keeping his head up, meeting Nat’s gaze with that same air of willingness to cut people a break, Andy Gibb, Nat Jaffe, whomever. Nat’s humming turned soft and lullaby-like as the two considered each other. Baby Rolando had a nice, solid feel to him, a bunch of rolled socks stuffed inside one big sock, dense and sleepy, not one of those scrawny flapping-chicken babies one ran across from time to time.

“I used to have a baby,” Nat recalled, sounding elegiac.

“I remember.” That was back around the time he first met Nat, playing a wedding at that Naturfreunde club up on Joaquin Miller. Archy, just back from the Gulf, came in at the last minute, filling in for Nat’s regular bassist at the time. Now the former Baby Julius was fifteen and, to Archy at least, more or less the same sweet freakazoid as always. Hearing secret harmonies, writing poetry in Klingon, painting his fingernails with Jack Skellington faces. Used to go off to nursery school in a leotard and a tutu, come home, watch Color Me Barbra. Even at three, four years old, prone like his father to holding forth. Telling you how french fries didn’t come from France or German chocolate from Germany. Same tendency to get caught up in the niceties of a question. Lately, though, he seemed to spend a lot of time transmitting in some secret teenager code, decipherable only by parents, designed to drive them out of their minds.

“Babies are cool,” Nat said. “They can do Eskimo kisses.” Nat and Rolando went at it, nose to nose, the baby hanging there, putting up with it. “Yeah, Rolando’s all right.”

“That’s what I thought.”

“Got good head control.”

“Doesn’t he, though?” Archy said.

“That’s why they call him Head-Control Harry. Right? Sure it is. Head-Control Harry. You want to eat him.”

“I guess. I don’t really eat babies all that much.”

Nat studied Archy the way Archy had studied the A-side of the late Bob Benezra’s copy of Kulu Sé Mama (Impulse!, 1967), looking for reasons to grade it down.

“So, what, you practicing? That the idea?”

“That was the idea.”

“And how’s it working out?”

Archy shrugged, giving it that air of modest heroism, the way you might shrug after you had been asked how in God’s name you managed to save a hundred orphans trapped in a flaming cargo plane from collision with an asteroid. As he played it off to Nat, Archy knew—felt, like the baby-shaped ache in his left arm—that neither his ability nor his willingness to care for Rolando English for an hour, a day, a week, had anything whatsoever to do with his willingness or ability to be a father to the forthcoming child now putting the finishing touches on its respiratory and endocrine systems in the dark laboratory of his wife’s womb.

Wiping a butt, squeezing some Carnation through a nipple, mopping up the milk puke with a dishrag, all that was mere tasks and procedures, a series of steps, the same as the rest of life. Duties to pull, slow parts to get through, shifts to endure. Put your thought processes to work on teasing out a tricky time signature from On the Corner (Columbia, 1972) or one of the more obscure passages from The Meditations (Archy was currently reading Marcus Aurelius for the ninety-third time), sort your way one-handed through a box of interesting records, and before you knew it, nap time had arrived, Mommy had come home, and you were free to go about your business again. It was like the army: Be careful, find a cool dry place to stash your mind, and hang on until it was over. Except, of course (he realized, experiencing the full-court press of a panic that had been flirting with him for months, mostly at three o’clock in the morning when his wife’s restless pregnant tossing disturbed his sleep, a panic that the practice session with Rolando English had been intended, vainly, he saw, to alleviate), it never would be over. You never would get through to the end of being a father, no matter where you stored your mind or how many steps in the series you followed. Not even if you died. Alive or dead or a thousand miles distant, you were always going to be on the hook for work that was neither a procedure nor a series of steps but, rather, something that demanded your full, constant attention without necessarily calling on you to do, perform, or say anything at all. Archy’s own father had walked out on him and his mother when Archy was not much older than Rolando English, and even though, for a few years afterward, as his star briefly ascended, Luther Stallings still came around, paid his child support on time, took Archy to A’s games, to Marriott’s Great America and whatnot, there was something further required of old Luther that never materialized, some part of him that never showed up, even when he was standing right beside Archy. Fathering imposed an obligation that was more than your money, your body, or your time, a presence neither physical nor measurable by clocks: open-ended, eternal, and invisible, like the commitment of gravity to the stars.

“Yeah,” Nat said. For a second the wire in him went slack. “Babies are cute. Then they grow up, stop taking showers, and beat off into their socks.”

There was a shadow in the door glass, and in walked S. S. Mirchandani, looking mournful. And the man had a face that was built for mourning, sag-eyed, sag-jowled, lamentation pooling in the spilt-ink splash of his beard.

“You gentlemen,” he said, always something elegiac and proper in his way of speaking the Queen’s English, some remembrance of a better, more civilized time, “are fucked.”

“I keep hearing that,” Archy said. “What happened?”

“Dogpile,” Mr. Mirchandani said.

“Fucking Dogpile,” Nat agreed, humming again.

“They are breaking ground in one month’s time.”

“One month?” Archy said.

“Next month! This is what I am hearing. Our friend Mr. Singletary was speaking to the grandmother of Mr. Gibson Goode.”

Nat said, “Fucking Gibson Goode.”

Six months prior to this morning, at a press conference with the mayor at his side, Gibson “G Bad” Goode, former All-Pro quarterback for the Pittsburgh Steelers, president and chairman of Dogpile Recordings, Dogpile Films, head of the Goode Foundation, and the fifth richest black man in America, had flown up to Oakland in a customized black-and-red airship, brimming over with plans to open a second Dogpile “Thang” on the long-abandoned Telegraph Avenue site of the old Golden State market, two blocks south of Brokeland Records. Even larger than its giant predecessor near Culver City, the Oakland Thang would comprise a ten-screen cineplex, a food court, a gaming arcade, and a twenty-unit retail galleria anchored by a three-story Dogpile media store, one floor each for music, video, and other (books, mostly). Like the Fox Hills Dogpile store, the Oakland flagship would carry a solid general-interest selection of media but specialize in African-American culture, “in all,” as Goode put it at the press conference, “its many riches.” Goode’s pockets were deep, and his imperial longings were married to a sense of social purpose; the main idea of a Thang was not to make money but to restore, at a stroke, the commercial heart of a black neighborhood cut out during the glory days of freeway construction in California. Unstated during the press conference, though inferable from the way things worked at the L.A. Thang, were the intentions of the media store not only to sell CDs at a deep discount but also to carry a full selection of used and rare merchandise, such as vintage vinyl recordings of jazz, funk, blues, and soul.

“He doesn’t have the permits and whatnot,” Archy pointed out. “My boy Chan Flowers has him all tangled up in environmental impacts, traffic studies, all that shit.”

The owner and director of Flowers & Sons funeral home, directly across Telegraph from the proposed Dogpile site, was also their Oakland city councilman. Unlike Singletary, Councilman Chandler B. Flowers was a record collector, a free-spending fiend, and without fully comprehending the reasons for his stated opposition to the Dogpile plan, the partners had been counting on it, clinging to the ongoing promise of it.

“Evidently something has changed the Councilman’s mind,” said S. S. Mirchandani, using his best James Mason tone: arch and weary, hold the vermouth.

“Huh,” Archy said.

There was nobody in West Oakland more hard-ass or better juiced than Chandler Flowers, and the something that evidently had changed his mind was not likely to have been intimidation.

“I don’t know, Mr. Mirchandani. Brother has an election coming,” Archy said. “Barely came through the primary. Maybe he’s trying to stir up the base, get them a little pumped. Energize the community. Catch some star power off Gibson Goode.”

“Certainly,” said Mr. Mirchandani, his eyes saying no way. “I am sure there is an innocent explanation.”

Kickbacks, he was implying. A payoff. Anybody who managed, as Mr. Mirchandani did, to keep a steady stream of cousins and nieces flowing in from the Punjab to make beds in his motels and wash cars at his gas stations without running afoul of the authorities at either end, was likely to find his thoughts running along those lines. It was almost as hard for Archy to imagine Flowers—that stiff-necked, soft-spoken, and everlastingly correct man, a hero in the neighborhood since Lionel Wilson days—taking kickbacks from some showboating ex-QB, but then Archy tended to make up for his hypercritical attitude toward the condition of vinyl records by going too easy on human beings.

“Anyways, it’s too late, right?” Archy said. “Deal already fell through. The bank got cold feet. Goode lost his financing, something like that?”

“I don’t really understand American football,” said S. S. Mirchandani. “But I am told that when he was a player, Gibson Goode was quite famous for something called ‘having a scramble.’”

“The option play,” Nat said. “For a while there, he was pretty much impossible to sack.”

Archy took the baby back from Nat Jaffe. “G Bad was a slippery motherfucker,” he agreed.

Mr. Nostalgia, forty-four, walrus mustache, granny glasses, double-extra-large Reyn Spooner (palm trees, saw grass, woodies wearing surfboards), stood behind the Day-Glo patchwork of his five-hundred-dollar exhibitor’s table, across a polished concrete aisle and three tables down from the signing area, under an eight-foot vinyl banner that read MR. NOSTALGIA’S NEIGHBORHOOD, chewing on a Swedish fish, unable to believe his fucking eyes.

“Yo!” he called out as the goon squad neared his table: two beefy white security guys in blue poly blazers and a behemoth of a black dude, Gibson Goode’s private muscle, whose arms in their circumference were a sore trial to the sleeves of his black T-shirt. “A little respect, please!”

“Damn right,” said the man they were escorting from the hall, and as they came nearer, Mr. Nostalgia saw that it really was him. Thirty years too old, twenty pounds too light, forty watts too dim, maybe: but him. Red tracksuit a size too small, baring his ankles and wrists. Jacket waistband riding up in back under a screened logo in yellow, a pair of upraised fists circled by the words BRUCE LEE INSTITUTE, OAKLAND, CA. Long and broad-shouldered, with that spring in his gait, coiling and uncoiling. Making a show of dignity that struck Mr. Nostalgia as poignant if not successful. Everybody staring at the guy, all the men with potbellies and back hair and doughy white faces, heads balding, autumn leaves falling in their hearts. Looking up from the bins full of back issues of Inside Sports, the framed Terrible Towels with their bronze plaques identifying the nubbly signature in black Sharpie on yellow terry cloth as that of Rocky Bleier or Lynn Swann. Lifting their heads from the tables ranged with rookie cards of their youthful idols (Pete Maravich, Robin Yount, Bobby Orr), with canceled checks drawn on long-vanished bank accounts of Ted Williams or Joe Namath; unopened cello packs of ’71 Topps baseball cards, their fragile black borders pristine as memory, and of ’86 Fleer basketball cards, every one holding a potential rookie Jordan. Watching this big gray-haired black man they half-remembered, a face out of their youth, get the bum’s rush. That’s the dude from the signing line. Was talking to Gibson Goode, got kind of loud. Hey, yeah, that’s what’s-his-face. Give him credit, the poor bastard managed to keep his chin up. The chin—him, all right—with the Kirk Douglas dimple. The light eyes. The hands, Jesus, like two uprooted trees.

“Consider yourselves fortunate, gentlemen,” Mr. Nostalgia called as they swept past his table. “That man could kill you with one finger if he wanted to.”

“Awesome,” said the younger of the goons, head shaved clean as a porn star’s testicle. “Long as he buys a ticket first.”

Mr. Nostalgia was not a troublemaker. He liked to smoke prescription indica, watch television programs about World War II, eat Swedish fish, and listen to the Grateful Dead, in any combination or grouping thereof. Undoubtedly, sure, he had issues with authority, his father a survivor of two camps, his mother a marcher on Washington, Mr. Nostalgia unfit to hold down any job requiring him to answer to a boss. Great as he might be in circumference, however, Mr. Nostalgia was only five-six, almost, in his huaraches, and not quite in fighting trim. His one reliable move, if you hoped to base a style of kung fu on it, you would probably have to go with Pill Bug. Mr. Nostalgia avoided beefs, quarrels, bar fights, and showdowns foreign and domestic. He deplored violence, except in 1944, in black and white, on television. He was a merchant of good reputation and long standing who had forked over a hefty fee to the organizers of the East Bay Sports and Card Show, some of which money had gone to pay for the protection, the peace of mind, that these goons in their blue blazers would, at least in theory, provide. And peace of mind, face it, was not merely a beautiful phrase; it was a worthy ambition, the aim of religions, the promise of underwriters. But Mr. Nostalgia, as he would afterward explain to his wife (who would sooner eat a bowl of mashed Ebola than attend another card show), was deeply outraged by the rough treatment to which a hero of his youth was being subjected, for no reason other than his having managed to ninja himself onto the floor of the Convention Center without a ticket. And so, on that Saturday morning in the Kaiser Center, Mr. Nostalgia surprised himself.

He came out from behind the ramparts of his neighborhood—replete as a Vegas buffet with choice offerings in the nonsports line that he had made his specialty and métier, among them a complete set of the 1971 Bobby Sherman Getting Together cards, including the very tough number 54. Mr. Nostalgia moved with a stately glide that had led at least one uncharitable observer over the years to remark, seeing him go by in one of his floral numbers, that the Pasadena Rose Parade appeared to be missing a float.

“Wait up, let me get the man a ticket,” he called after the retreating security escort.

Gibson Goode’s bodyguard glanced over his shoulder for half a second, like he was verifying that he hadn’t just stepped in dog shit. The goons in the blue blazers kept walking.

“Hey, yo!” Mr. Nostalgia said. “Come on! Hey, come on, you guys! That’s Luther Stallings.”

It was Stallings who came to a stop first, digging in, bucking his captors, turning to confront his redeemer. The familiar smile—its charm gapped and stained by drugs or prison dentistry or maybe only by the kind of poverty that would lead you to try to skirt an eight-dollar admission fee—put an ache behind Mr. Nostalgia’s breastbone.

“Thank you, my good man,” Stallings said. Ostentatious, showing up the goons. “My dear friend . . .”

Mr. Nostalgia supplied his actual last name, which was long, Jewish, and comical, a name for a type of cheese or sour bread. Stallings repeated it flawlessly and without the hint of mockery that it typically inspired.

“My friend here,” Stallings explained, shouldering free of the goons like an escape artist shrugging out of a straitjacket, “has kindly offered to float me the price of admission.”

A slight rise in intonation at the end, almost putting a question mark there. Making sure he had his facts right.

“Absolutely,” Mr. Nostalgia said. He remembered sinking deep into a greasy Herculon seat at the Carson Twin cinema, a Saturday afternoon thirty years ago, an elephant of joy sitting on his chest, watching a movie with a mostly black cast—it was a mostly black audience—called Night Man. In love with every single thing about that movie. The girl in her silver Afro. The hand-to-hand fighting. The funky soundtrack. A chase involving a green 1972 Saab Sonett driven at top speed through streets that were recognizably those of Carson, California. The gear, tackle, and explosives carried by the bank robbers. Above all, the movie’s star, loose-limbed, still, and taciturn like a McQueen hero and with the same willingness to look silly, which was another way of saying charm. And—indisputably, in 1973—a Master of Kung Fu. “It’s truly an honor.”

The goons zoomed in on Mr. Nostalgia, training their scopes, scanning the green two-day exhibitor’s pass hanging from a lanyard around his neck. Faces going dull, losing some of their bored swagger as they tried to remember if there was anything about this type of situation in the official goon manual.

“He was harassing Mr. Goode,” said Goode’s bodyguard, stepping in to shore up morale in the muscle department. “You buy him a ticket,” he told Mr. Nostalgia, “he just going to harass him some more.”

“Harassing?” Luther Stalling said, wild with incredulity. Innocent of every crime of which he ever had or ever would be accused for all time. “How I’m harassing that man? I just want to get with him, have my thirty seconds at his feet, standing on line like everybody else. Get my autograph off him, go about my way.”

“Straight autograph from Mr. Goode going to cost you forty-five dollars,” the bodyguard pointed out. For all his girth, height, and general monstrousness, his voice was gentle, patient, the man paid, basically, to suffer fools. Maintain a fool-free perimeter around G Bad without making his employer look like a dick. “How you going to pay that, you ain’t even have eight?”

“Buddy, hey, yo,” Stallings said, then got the name right again with another painful flash—painful to Mr. Nostalgia, at any rate—of that scrimshaw smile. Whatever the man had been doing, apart from simply getting old, to have so brutally pared himself down, hollowed himself out, since his glory days, it didn’t seem to affect his memory; or maybe he wasn’t doing it anymore. “I hope, I, uh, wonder,” going all in with the question mark this time, “if maybe I could persuade you to help me out?”

Mr. Nostalgia stepped back, an involuntary move ingrained by years of tangling with the hustlers, operators, schnorrers, and short-change artists who flecked the world of card shows like weevils in flour. Thinking there was a difference of more than thirty-seven dollars between offering to pick up the price of admission, a gesture of respect, and springing for the man to buy himself, of all things, a Gibson Goode autograph. Mr. Nostalgia tried to remember if he had ever seen or even heard of a celebrity (however well forgotten) who was prepared to stand in line to pay cash for another celebrity’s signature. Why did Stallings want it? Where was he going to have G Bad put it? He did not appear to be carrying any obvious signables, book, photograph, jersey, not even a program, a napkin, a Post-it. I just want to get with him. To what end? Mr. Nostalgia never could have flourished in his trade without maintaining a keen ear for the slick lines of grifters and bullshit artists, and Luther Stallings was definitely setting off Klaxons, up to something, working some angle. Had already blown his play, in fact, until Mr. Nostalgia for some reason had felt it necessary to leave the safety of his neighborhood and stick his nose where it didn’t belong. Mr. Nostalgia could hear his wife passing the sole necessary judgment on the matter, another in the string of endless variations on her single theme, What in God’s name were you thinking? But Mr. Nostalgia’s title was not a mere honorific; his d/b/a was his DNA. Remembering the weight of that elephant of happiness upon him, on that Saturday afternoon at the Carson Twin in 1974, he chose to believe in the truth of Luther Stallings. A man could want things far stranger and less likely than a quarterback’s signature on a scrap of cash register tape or a torn paper bag.

“Maybe I can do better than that,” Mr. Nostalgia said.

He reached into the back pocket of his denim shorts and took out a folded, sweat-dampened manila envelope. Inside it were the other two green badges on lanyards to which, at his level of participation, he was entitled. He fished out one badge and pushed his way through the screen of goons. Luther Stallings bowed his head, revealing an incipient Nelson Mandela bald spot, and Mr. Nostalgia bestowed the badge on him, Oz emboldening the Lion.

“Mr. Stallings is working for me today,” he said.

“That’s right,” Stallings said at once, sounding not just sincere but impatient, like he had been looking forward for days to helping out in Mr. Nostalgia’s booth. His eyes had flicked, barely, across the badge as Mr. Nostalgia hung it on him; he said, not missing a trick, “In Mr. Nostalgia’s Neighborhood.”

“Working how?” said the older of the two goons.

“He’s doing a signing at my booth,” Mr. Nostalgia said. “I got a complete and a partial set, no Bruce Lee, of the Masters of Kung Fu series, I got a few other things Mr. Stallings has kindly consented to sign. A lobby card from Black Eye, I’m pretty sure.”

“‘Masters of Kung Fu,’” Stallings repeated, barely managing to avoid sounding like he had absolutely no idea what Mr. Nostalgia was talking about.

“Donruss, 1976, it’s a tough set.”

Four clueless looks sought enlightenment at the hands of Mr. Nostalgia.

“Uh, guys?” Mr. Nostalgia said with a circular sweep of his hands, taking in the echoing space all around them. “Trading cards? Little rectangles of cardboard? Stained with bubble gum? Pop one in the spokes of your bicycle, make it sound like a Harley-Davidson?”

“Damn, seriously?” Stallings could not keep it back. “Masters of Kung Fu. They got a Luther Stallings in there?”

“Naturally,” Mr. Nostalgia said.

“Luther Stallings.” The older of the two blue blazers, lank dark hair, the flowerpot skull and triangle chin of a Russian or a Pole, about Mr. Nostalgia’s age, tried out the name. Scrunching up one side of his face like he was screwing a loupe into his eye socket. “Okay, yeah. What’s it? Strutter. Seriously, that’s you?”

“My first part,” Stallings said, seizing upon this unexpected opportunity to preen. Loving it. Putting one of those massive antler hands on Mr. Nostalgia to let him know he was loving it: doing what he must do best. Restoring the goon squad to their proper roles as members of the Luther Stalling Irregulars. “Year after I won the title.”

“Title in what? Kung fu?”

“Wasn’t one at that time. Was in karate. In Manila. World champion.”

“World champion, bullshit,” said Goode’s bodyguard. “I give you that.”

Stallings flat ignored the big man. Mr. Nostalgia, feeling fairly balls-out pleased with himself, tried to do the same.

“We all done here, gentlemen?” Stallings asked the blue blazers.

The security guys in the blue blazers checked in with the bodyguard, who shook his head, disgusted.

“I tell you what, Luther,” the bodyguard said. “You even flick a boogie in Mr. Goode’s general vicinity, I will come down on you, motherfucker. And I will show no mercy.”

The man turned and, with a forbearing hitch in his walk, rolled back to the signing table where his boss, head shaved to stubble, wearing a black polo shirt with a red paw print where the alligator would have gone, armed with nothing but a liquid-silver marker and a high-priced smile, sat fighting his way through an impressively long line of autograph seekers. Game-worn jerseys, game-used footballs, cards, ball caps, he was going to clear nine, ten thousand today.

“Yeah, whatever,” Stallings said, as if he could not care less about Gibson Goode.

Working up a surprising amount of swagger, he followed Mr. Nostalgia to the booth. You would have thought the man had just saved himself from being tossed out of the building by the goon squad. Mr. Nostalgia recognized objectively that he ought to be annoyed, but somehow it made him feel sorrier for Stallings.

“Wow, check this shit out.”

Stallings worked his gaze along the table, taking in the sealed wax packs of Garbage Pail Kids and Saturday Night Fever, the unopened box of Fleer Dune cards, the Daktari and Gentle Ben and Mork & Mindy board games, the talking Batman alarm clock, the Aurora model kits of the Spindrift and Seaview in their original shrink-wrap.

“They even got cards for that ALF, huh?” he said.

His voice as he made this observation, like his expression as he took it all in, sounded unhappy to Mr. Nostalgia, even forlorn. Not the disdain that Mr. Nostalgia’s wife always showed for his stock-in-trade but something more like disappointment.

“Used to be pretty standard for a hit show,” Mr. Nostalgia said, wondering when Stallings would get around to hitting him up for the forty-five dollars. “Nothing much of interest in that set.”

Though Mr. Nostalgia loved the things he sold, he had no illusion that they held any intrinsic value. They were worth only what you would pay for them; what small piece of everything you had ever lost that, you might come to believe, they would restore to you. Their value was indexed only to the sense of personal completeness, perfection of the soul, that would flood you when, at last, you filled the last gap on your checklist. But Mr. Nostalgia had never seen his nonsports cards so sharply disappoint a man.

“ALF, yeah, I remember that one,” Stallings said. “That’s real nice. Growing Pains, Mork & Mindy, uh-huh. Where the Masters of Kung Fu at?”

Mr. Nostalgia went around to a bin he had tucked under the table that morning after setting up and dug around inside of it. After a minute of moving things around in the bin, he came out with the partial set, the one that was missing the Lee and the Norris cards. “Fifty-two cards in the set,” he said. “You’re number, I don’t know, twelve, I think it is.”

Stallings shuffled through the cards, whose imagery depicted, bordered by cartoon bamboo, labeled with takeout-menu-style fake Chinese lettering, a fairly indiscriminate mixture of real and fictitious practitioners (Takayuki Kubota, Shang-Chi) of a dozen forms of martial arts in addition to the eponymous one, including bartitsu (Sherlock Holmes) and savate (Count Baruzy). At last Stallings came up with his card. Stared at the picture, made a sound like a snort through his nose. The card featured a color still from one of his movies, poorly reproduced. A young Luther Stallings, in red kung fu pajamas, flew across the frame toward a line of Chinese swordsmen, feet first, almost horizontal.

“Damn,” Stallings said. “I don’t even remember what that’s from.”

“Take it,” Mr. Nostalgia said. “Take the whole set. It’s a present, from me to you, for all the pleasure your work has given me over the years.”

“How much you get for it?”

“Well, the set, like I said, it’s pretty tough. I’m asking five, but I’d probably take three. Might go for seven-fifty with the Bruce Lee, the Chuck Norris.”

“Chuck Norris? Yeah, I went up against the motherfucker. Three times.”

“No joke.”

“Kicked his ass all over Taipei.”

Mr. Nostalgia figured he could look it up later if he wanted to break some small, previously unbroken place in his own leaf-buried heart. “Go on,” he said. “It’s yours.”

“Yeah, hey, thanks. That’s really nice. But, uh, no offense, I’m already so, like, overburdened, you know what I’m saying, with stuff out of the past I’m carrying around.”

“Oh, no, sure—”

“I just hate to add to the pile.”

“I totally understand.”

“Got to keep mobile.”

“Of course.”

“Travel light.”

“Right-o.”

“How much,” Luther Stallings said, lowering his voice to a near-whisper. Swallowing, starting over, louder the second time. “How much you get for my card by itself.”

“Oh, uh,” Mr. Nostalgia said, understanding a microsecond or two too late to pull off the lie that he was going to have to tell it. “A hundred. Ninety, a hundred bucks.”

“No shit.”

“Like around ninety.”

“Uh-huh. Tell you what. You give me this one card, Luther Stallings in . . . I’m going to make a wild guess and say it was Enter the Panther.”

“Has to be.” Mr. Nostalgia felt the play begin again, the game that Luther Stallings was trying to run on him and, somehow, on Gibson Goode.

“And I’m a sign it, okay?” Here it came. “Then I’m a trade it back to you for forty-five bucks.”

“Okay,” Mr. Nostalgia said, feeling unaccountably saddened, crushed, by the pachyderm weight of a grief that encompassed him and Stallings and every man plying his lonely way in this hall through the molder and dust of the bins. The world of card shows had always felt like a kind of true fellowship to Mr. Nostalgia, a league of solitary men united in their pursuit of the lost glories of a vanished world. Now that vision struck him as pie in the sky at best and as falsehood at the very worst. The past was irretrievable, the league of lonely men a fiction, the pursuit of the past a doomed attempt to run a hustle on mortality.

“If that’s how you want it,” Mr. Nostalgia said. He was not averse, in principle, to raising the five-dollar value of the Stallings card by a factor of three or four. But as he handed Stallings the gold-filled Cross pen, a bar mitzvah gift from his grandparents that he liked to use when he was getting something signed for his own collection, he wished that he had never come out from behind the table, had let the security guards sweep Luther Stallings past Mr. Nostalgia’s Neighborhood and clear on out of the Kaiser Center.

Over the course of the next half hour, he checked on Stallings a couple of times as the man made his way to the end of the signing line for Gibson Goode, then inched his way to the front one lonely man at a time. In the middle of selling a 1936 Wolverine gum card, “The Fight with the Shark,” for $550 to a dentist from Danville, Mr. Nostalgia happened to glance over and see that Luther Stallings had regained his place at the front. The bodyguard got to his feet looking ready, as promised, to suspend mercy, but after a brownout of his smile, Gibson Goode reached for the bodyguard and gently stiff-armed him, palm to the big man’s chest, and the big man, with a mighty headshake, stepped off. Words passed between Goode and Stallings—quietly, without agitation. To Mr. Nostalgia, reading lips and gestures, sometimes able to pick up a word, a phrase, the conversation seemed to boil down to Gibson Goode saying no repeatedly, with blank politesse, while Luther Stallings tried to come up with new ways of getting Goode to say yes.

There was only so much of this that the people in line behind Luther Stallings were willing to put up with. A rumor of Stallings’s earlier outburst, his near-ejection, began to circulate among them. There was a certain amount of moaning and kvetching. Somebody gave voice to the collective desire for Stallings to Come on!

Stallings ignored it all. “You asked him?” he said, raising his voice as he had done an hour ago, when the blue blazers came to see how he might like to try getting himself tossed. “You asked him about Popcorn?” Talking loudly enough for Mr. Nostalgia and everybody in the neighborhood to hear. “Then I got the man for you. Hooked him. You know I did.”

The expressions of impatience, general down the line, rose to outright jeering. Stallings turned on the crowd, trying to scowl them into silence, snapping at a man in a Hawaiian shirt standing two guys behind him. The man said, “No, fuck you!”

Wading into the signing area, arms windmilling to reach for Stallings in a kind of freestyle of aggression, came the two blue blazers, Shaved Ball and the Soviet. They took brusque hold of Stallings’s arms, faces compressed as if to resist a stink, and jerked his arms back and toward his spine.

Two seconds later, no more, Shaved Ball and the Soviet were lying flat on their backs on the painted cement floor of the hall. Mr. Nostalgia could not have said for certain which of them had taken the kick to the head, which the punch to the abdomen, or if Luther Stallings had even moved very much at all. As they’d gone tumbling backward, the line of autograph seekers had shuddered, rippled. Human turbulence troubled all the surrounding lines, people waiting for Chris Mullin, Shawn Green.

“Bitch,” Stallings said, turning back to Gibson Goode, in his polo shirt, with his sockless loafers. “I want my twenty-five grand!”

Gibson Goode, being Gibson Goode, Mr. Nostalgia supposed, might have had no choice in the matter: He kept, as his legend said he must, his cool. The same quiet, restraining hand against his bodyguard’s chest. Unintimidated. Still smiling. He took out his wallet, opened it, and counted out ten bills, rapid-fire. Slid them across the signing table. Luther Stallings studied them, head down, chest rising and falling. The money lay there, exciting comment in the line, ten duplicate cards from the highly collectable Dead Presidents series. Luther shook his head once. Then he reached down and took the money. Resigned—long since resigned, Mr. Nostalgia thought—to doing things he knew he was going to regret. When he went past Mr. Nostalgia’s table, without so much as a thank-you, he had not managed to get his chin up again.

It was only later, as a voice on the PA was chasing stragglers from the hall and the lights went out over the signing area, that Mr. Nostalgia noticed Luther Stallings had walked off with his gold pen.

On a Saturday night in August 1973, outside the Bit o’ Honey Lounge, a crocodile-green ’70 Toronado sat purring its crocodile purr. Its chrome grin stretched beguiling and wide as the western horizon.

“Define ‘toronado,’” said the man riding shotgun.

Behind his heavy-rimmed glasses, he had sleepy eyes, but he scorned sleep and frowned upon the somnolence of others. In defiance of political fashion, he greased his long hair, and its undulant luster was clear-coat deep. His name was Chandler Bankwell Flowers III. His grandfather, father, and uncles were all morticians, men of sobriety and pomp, and he inhabited a floating yet permanent zone of rebellion against them. Nineteen months aboard the Bon Homme Richard had left Chan Flowers with an amphetamine habit and a tattoo of Tuffy the Ghost on the inside of his left forearm. The shotgun, holstered in a plastic trash bag alongside his right leg, was a pump-action Mossberg 500.

“‘Define’ it?” said the driver, Luther Stallings, not giving the matter his full attention. His eyes, green flecked with gold, kept finding excuses to visit the rearview mirror. “It’s the name of a car.”

“But what does it mean? What is the definition of the word ‘toronado.’ Tell me that.”

“You tell me,” Luther said, more wary now.

“It’s a question.”

“Yeah, but what are you really asking?”

“Toro-nah-do.” Chan strumming the “R” like a string of Ricky Ricardo’s guitar. “You’re driving it. Talking about it. In love with it. Don’t even know what it means.”

Luther massaged the leather cover on the steering wheel as if feeling for a cyst. He took another glance in the mirror, then leaned forward to look past Chan at the Bit o’ Honey’s front door. Where Chan ran to dark and stocky, Luther Stallings was long and light-skinned, with an astronaut chin. He had served one tour in the U.S. Army, most of it spent splintering planks with his feet for a hand-to-hand combat demonstration team. He was dressed as for dancing, tight plaid bell-bottom slacks, a short-sleeved terry pullover. His hair rose freshly stoked into a momentous Afro.

“I believe it is Spanish,” Luther said. “A common expression, can be loosely translated to ‘suck my dick.’”

“Vulgar language,” Chan said, drawing on his rich patrimony of improving maxims. That stiff mortuary grammar, hand-beaten into him by his old man, had always embarrassed him when they were youngsters. In this hoodlum revolutionary phase he was going through, Chan flaunted the properness of his speech, a lily in the lapel of a black leather car coat. “Always the first and last refuge of the man with nothing to say.”

Luther broke free of the mirror to look at Chan. “Toronado,” he said, employing the imperative.

“You don’t know, do you?” Chan said. “Just admit. You are driving around, you paid three thousand dollars for this vehicle, cash, for all you know, a toronado’s, what, might be some kind of brush you use for cleaning a Mexican toilet bowl.”

“I don’t care what it—”

“Juanita, quick, get the toronado, I have diarrhea—”

“It means a bullfighter!” Luther said, rising to the bait despite long experience, despite needing to keep one eye on the rearview and one on the diamond-tufted vinyl door of the lounge, in spite of wanting to be a hundred years and a thousand miles away from this place and this night. “A fighter of bulls.”

“In Spanish,” Chan suggested in a mock-helpful tone.

Luther shrugged. When Chan was nervous, he got bored, and when he got bored, he would start trouble, any kind of trouble, just to break the tedium. But there was more to this line of questioning. Chan was mad at Luther and trying to hide it. Had been trying for days to hold his anger close, like the Spartan boy with the fox in his shirt, let it feast on his intestines rather than cop to hiding it.

“‘Bullfighter,’” Chan said with bitter precision, “is torero.”

He bent down to scoop a handful of twelve-gauge cartridges from a box between his feet and pocketed them at the hip of his tweed blazer. His hair, heavy with pomade, gave off a dismaying odor of flowers left too long in a vase, putrid as envy itself.

“Then uh, ‘tornado,’” Luther tried.

This was such a contemptible suggestion that Chan, who generally never lacked for verbal expressions of contempt, could dignify it only with a smirking shake of his head. Luther was about to point out that it was he, the ignorant one, who’d just laid down thirty-two hundred-dollar bills for the beautiful car with the mysterious name, while Professor Flowers remained a frequent denizen of the buses.

“Chan, you captious motherfucker—” he began, but then stopped.

From another pocket of his tweed blazer, patches on the elbows, Chan drew a pair of sateen gloves, dark purplish blue. Shoddy things, busted at the seams, tricked out with pointy fish fins. Last Halloween, Chan’s little brother, Marcel, out trick-or-treating in a Batman suit, had been hit by a car and killed. Drunken negroes in a Rambler American, boy stepping off the curb with his face too small to really fit the eyeholes of the mask. Chan had some tiny hands, but even so, the gloves were a tight fit, and as he pulled them on, they split some more.

When Luther saw Chan wearing Marcel’s purple crime-fighting gloves, he didn’t know what to say. He threw another glance at the rearview: Telegraph Avenue nocturne, a submarine wobble of light and shadow. Chan reached into the garbage bag, came out with a bat-eared mask stamped from flimsy plastic. He slipped the elastic string over the back of his head, parked the borrowed face at the top of his forehead.

“Okay,” Luther said at last, the second smartest boy in the room every day of his life from 1955 to the day in 1971 that had Chan shipped out, “tell me what it means.”

A girl, at key points also constructed like the car along a beguiling x axis, came out of the Bit o’ Honey Lounge. She wore tight white jeans whose flared legs bellied like sails. Her hair was tied back shiny against her head to emerge aft in a big puffball. Her feet rode the howdahs of swaying platform sandals. As she sauntered past the car, she pulled the tails of her short-sleeved madras shirt from the waist of her jeans, knotting them together under her breasts.

“That’s it,” Luther said. He pressed down on the clutch and readied his hand on the gearshift. “Go if you’re going.”

Chan lowered the mask over his face, and Luther saw that it had been painted top to bottom, matte black paint effacing the line that marked the bottom edge of Batman’s cowl, paint sprayed over the heroic molded chin dimple, the affable molded smile. Behind the mask, Chan’s eyes glistened like organs exposed by two incisions.

“Jungle action,” Chan said behind the baffle of the mask. “Oh, and by the way.” He shouldered open the passenger door and sprang out of the car. The shotgun in the garbage bag hung by his side like a workaday implement. “‘Toronado’ doesn’t mean shit.”

Chan’s right arm snaked into the mouth of the garbage bag as, with his left hand, he grabbed hold of the brass handle of the upholstered front door of the club. He yanked the door open, flinging his right arm out to the side. The garbage bag flew off, revealing the riot gun that Chan had checked out that afternoon from the basement arsenal of a Panther safe house in East Oakland. There was a gust of horns, palaver, and thump, and then the door breathed shut behind Chan. The garbage bag caught on a thermal hook and spun in the air, teased and tugged by unseen hands.

Luther lowered the volume on the in-dash eight-track. City silence, the sigh of a distant bus, the tide of the interstate, Grover Washington, Jr., setting faint, intricate fires up and down the length of “Trouble Man.” Beyond that, nothing. Luther felt his attention beginning not so much to wander as to migrate, seeking opportunity elsewhere. Far down the coast highway, at the wheel of his beautiful green muscle car, he made his way to Los Angeles, capital of the rest of his life. In a helicopter shot, he watched himself rolling across an arcaded bridge with the ocean and the dawn and the last of the night spread out all around him.

He heard the stuttering crack of a number of firearms discharging at once. The door of the Bit o’ Honey banged open again, spraying horns and shouts. Chan came out at a running walk. He got into the car and slammed the door. Blood streaked his left shoe like a bright feather. The shotgun gave off its sweet, hellish smell, electricity and sizzling fatback.

Luther shifted into first gear, standing on the gas pedal, balanced on it, and on the moment like the trumpeter angel you saw from the Warren Freeway, perched at the tip of the Mormon temple, riding the wild spin of the world itself. Everything Detroit could muster in the way of snarling poured from the 450 engine. They parlayed a dizzying string of green lights all the way to Claremont Avenue. It had been a case of love at first sight for Luther and the Toronado two days before, at a used-car lot down on Broadway. Now, as they tore up Telegraph, something slid coiling through his belly, more like a qualm of lust. Chan tossed his brother’s Halloween mask out of the open window, slid the gun under the seat. He peeled away the gloves and started to throw them out, too, but in the end seemed to want to hold on to them, the right one bloody and powder-burned, a while longer. He sat there clutching them in one fist like a duelist looking for someone to slap.

At the Claremont intersection, with no one after them and no sign of the law, Luther eased the car into a red light. Just an ordinary motorist, window down, elbow hooked over the door, grooving on the passage of another summer evening. Somewhere in the vicinity, he had once been told, covered over by time and concrete, lay the founding patch of human business in this corner of the world. Miwok Indians dreaming the dream, living fat as bears, piling up their oyster shells, oblivious to history with its oncoming parade of motherfuckers.

“What happened?” Luther said to Chan, affecting lightness. Only then, in the wake of posing this awful question, did he begin to feel something like dread. Chan just turned up the volume on the music. “Chan, you did it?”

Luther could see Chan struggling to frame the story of what had transpired inside the Bit o’ Honey Lounge in some way that did not infuriate him. One thing Chandler Flowers hated more than being underestimated for his intelligence was giving evidence of any lack thereof. The light turned green. Luther steered, for mysterious reasons and in the absence of counterinstruction from his companion, toward the image in his mind of that westernmost angel blowing that apocalyptic horn. A minute went by which Joe Beck and his guitar organized according to their own notions of time and its fuzztone passage. At last Flowers emitted, as through a tight aperture, four words.

“Shot off his hand.”

“Left or right?”

“The right hand.”

“He a righty or a lefty?”

“Why?”

“Is Popcorn a righty or a lefty?”

“You are suggesting, if Popcorn Hughes turns out to be right-handed, maybe I messed this job up a little less. Because at least now Popcorn only has the hand he doesn’t use.”

Luther reflected as they rumbled up Tunnel Road toward the spot where, invisibly as a decision turning bad, it became the Warren Freeway. “No,” he conceded at last.

After this, they did not speak at all. Luther went on reflecting. At seven in the morning, Monday, he was expected to report to a rented soundstage down in Studio City to film his first scenes for Strutter, a low-budget action movie in whose lead he had recently been cast. He was driving around tonight in the up-front money from that job. There was ten grand yet to come, and after that, anything: sequels, endorsements, television work, the parts that Jim Brown was too busy to take, a costarring role with Burt Reynolds. Now, through some damned interlocking of bravado, loyalty, and the existential heedlessness that had helped him to become the 1972 middleweight karate champion of the world, Luther had knotted his pleasantly indistinct future like a sackful of kittens to the plunging stone of Chan Flowers.

Tonight had gone wrong, but even if Popcorn, as planned, had caught a fatal chestful of lead shot and pumped out his life in a puddle under a table by the stage, the situation would have been no better. True, the seed of Panther legend that Chan Flowers hoped to cultivate as Chan “the Undertaker” Flowers, killer of men—a real one, not some make-believe hard-ass in a low-budget grind-house feature—would have been planted. True, the ongoing mental distress caused to Huey Newton by the continued existence of Popcorn Hughes might have been assuaged. But there still would have been no benefit whatsoever to Luther Stallings. Success of the mission would have been another kind of failure, even deeper shit than Luther was in now.

Luther had no politics, no particular feelings toward drug dealers like Popcorn or toward the Black Panthers who had targeted them. He did not care who controlled the city of Oakland or its ghetto streets. He had seen Huey Newton once in his life, black leather jacket, easy smile, talking some shit about disalienation at a house party in the Berkeley flatlands, and had marked him right away as just another stylist of gangster self-love. Luther Stallings, future star of blaxploitation and beyond, had no call to be here, no interest in the outcome either way. Chan asked him to drive, so Luther drove. Now, instead of a murder in his rearview mirror, there was the bloody trail of a fuckup. Meanwhile, the image of the golden angel of the Mormons soloing atop his spire worked its strange allure on Luther’s imagination.

“Take a left,” Chan said as they rolled off the freeway at the Lincoln Avenue exit.

Luther was about to protest that a left turn would lead them away from the temple when he realized that he had no real reason to want to go to that place. The vague longing to bear some kind of witness to the glory of the angel Moroni winked out inside him, crumbled like ash. Luther aimed the Toronado up Joaquin Miller Road.

“Where we going?” he said.

“I need to think,” said the smartest boy in the room. He stared out at the night that streamed like a downpour across the windshield. Then, “Shut up.”

“I didn’t say nothing,” Luther said, though he most definitely had been tossing around some combination of words along the lines of Ain’t it a little late for that now?

“Yeah, I was in that Dogpile one time,” Moby was saying. “Down in L.A.?”

Moby was one of the noontime regulars. He was a lawyer, none too unusual a career path for a three-hundred-dollar-a-month abuser of polyvinyl chloride, except that Moby’s clients were all cetaceans. His real name was Mike Oberstein. He was notably—given the moniker—white and size 2XL. Wore his longish hair parted down the center and slicked back over his ears in twin flukes. Moby worked for a foundation out of an office in the same building as Archy’s wife, bringing action against SeaWorld on behalf of Shamu’s brother-in-law, suing the navy for making humpbacks go deaf. He was a passionate and free-spending accruer of fifties and sixties jazz sides.

“It was pretty tight,” Moby added.

“Was it?” Nat said. Giving a bottle to Rolando English, who sat fastened safely into an infant carrier, propped up on the counter by the cash register. Nat kept his gaze fixed on the baby so that, Archy understood, he would not have to kill Mike Oberstein with gamma rays shot out of his eyeballs. “Was it bangin?”

Archy knew—could not help knowing all the man’s rants and treatises on the subject—how it bothered Nat that Moby tried so hard (to be honest, probably wasn’t even trying anymore) to sound like he was from the ’hood, from round the way, as Moby would have put it, even though he was a sweet-natured white guy from Indiana, someplace.

“It was straight-up bangin,” Moby said, so well armored in his sweetness and his imaginary Super Fly fur coat that he was impervious if not oblivious to the eyeball lightning Nat was always forking in his direction. “No joke. Found me this crazy side called, Nat, get this, Jimmy Smith Live in Israel. Thought it was a myth. I been looking for that for, like, years.”

Nat nodded, watching the formula steadily disappear from the bottle, while in his imagination, as Archy could infer by the knot of Nat’s shoulders, he took a pristine pressing of Jimmy Smith Live in Israel (Isradisc, 1973) out of its sleeve and snapped it over his knee. Twice, into quarters. Then handed it back to Moby without a word, not even needing to say, Man, fuck Dogpile. And the motherfucking Dogpile blimp.

“Part I don’t understand, all due respect, is why y’all act like it some kind of invasion,” said the King of Bling. “Dogpile coming into this neighborhood.”

Garnet Singletary, Baby Rolando’s grandfather, was sitting beside Moby at the glass display counter that ran nearly half the length of the south wall of the store, at the end farthest from the window, in order to preserve a certain distance between himself and the parrot. Fifty-Eight, the African grey, sat perched on the shoulder of Cochise Jones, who occupied his usual stool tucked into the corner by the window, Mr. Jones with that inveterate hunch to his spine from fifty years conducting experiments at the keyboard of a Hammond B-3. Decades of avian companionship had raised a fuzz of claw marks at the shoulders of Mr. Jones’s green leisure suit, tussocks on the padded polyester lawn. Restless as a radio telescope, the parrot’s head with its staring eye plowed the universe for invisible signs and messages. Every so often Fifty-Eight, whose public utterances tended to be musical, would counterfeit the steely vibrato of his owner’s B-3, break out into a riff, a stray middle eight, the bird programming its musical selections with an apparent randomness in which Singletary, who feared and admired the bird, claimed to find evidence of calculation and ironical intent.

“Gibson Goode was born here,” Singletary continued when no explanation was forthcoming from either partner.

Singletary was in his mid-fifties but looked thirty. Hair sprang carefully from his head in micro-dreads no thicker than his grandson’s fingers. His smile easy and warm, his eyes as cold as pennies at the bottom of a well. Like Fifty-Eight’s, those eyes missed nothing, cloaking in a universal fog of conversation the ceaseless void of his surveillance. Archy wondered if the man’s unease around the bird arose from recognition of a rival or a peer.

Singletary said, “Man grew up down in L.A., but his granny still living over in Rumford Plaza. Y’all was operating in Atlanta, New York, and this dude showed up in his great big black blimp, I might understand how you could feel some resentfulness. But Gibson Goode is a semi-local product. Like”—the eyes teaming up with the smile to give notice that he was about to mess with Nat—“if you was to put you and Archy together. Half local, half out of town.”

“Half and half,” Nat said, humming to himself, pouring the formula into Rolando English. The boy definitely had an appetite; they had run through the bottles of Good Start by eleven this morning and were working on a can of Enfamil powder mixed with water at Brokeland’s bathroom sink, the Enfamil provided by S. S. Mirchandani from a deep, remote, and spidery shelf over at Temescal Liquor, which he owned. The infant carrier came courtesy of the King of Bling.

“Look at him go.” Cochise Jones watched the baby formula work its way like mercury in a falling thermometer down the graduations. Intent, pleased, doubtful, as if he had money riding on the outcome. He winked at Archy. Mr. and the late Mrs. Jones never had children of their own. “Boy making me thirsty.”

“Yes, I am feeling quite thirsty myself,” said Mr. Mirchandani, and Archy felt a flutter of anticipatory dread. “You know, Nat, you really should put in an espresso machine or other form of beverage service.”

Archy plunged himself deeper into the mysteries of crate number 8. The theoretical espresso machine was a sore subject, the most recent of many arguments between the co-owners of Brokeland having begun over the question of whether, as Archy had been hinting with increasing heavy-handedness for a couple of years, the time had come to offer more at the counter than unlimited supplies of music and bullshit on tap. Because the truth was, they were already fucked, with or without Gibson Goode and his Dogpile empire. They were behind on the rent to Singletary. Their inventory was dwindling as their ability to purchase the better collections ran afoul of cash flow problems. Probably if you looked at the matter coolly and rationally, an activity in which neither partner could be said to excel, they were on their last legs. So many of the other used-record kings of the East Bay had already gone under, hung it up, or turned themselves into Internet-only operations, closing their doors, letting the taps of bullshit go dry. Brokeland Records was nearly the last of its kind, Ishi, Chingachgook, Martha the passenger pigeon.

Every time Archy broached the subject of trying some new angle, branching out, beefing up their website, even, yes, selling coffee drinks and pastries and chai, he ran into heavy resistance from Nat. Not just resistance; the man would shut down the conversation, shut himself down, with that infuriating, self-righteous Abraham the Patriarch way he had sometimes, acting as if he and Archy were not a couple of secondary-market retailers trying to stay afloat but guardians of some ancient greatness that must never be tainted or altered. When really (like any religion, Archy supposed), it was a compound of OCD and existential panic, a displaced fear of change. Reroutings of familiar traffic patterns, new watermarks and doodads on the national currency, revised rules for the bundling of recyclables, such things were anathema to Nat Jaffe. Fresh starts, clean slates, reboots: anathema. He stood against them like an island in the flow, a snag of branches.

“You want a fucking macchiato?” he had said a couple of days earlier, throwing a record album at Archy, nothing too valuable, just a copy of Stan Getz and J. J. Johnson at the Opera House (Verve, 1957), Getz sitting in with Johnson, Oscar Peterson, Ray Brown, and Connie Kay. “Here’s your fucking macchiato!”

Meaning, sweet light froth of a white guy on top of a dense dark bottom of black. The shot had gone wide, but damn, a flying record, the thing could have sliced Archy’s head off. Archy found himself annoyed just thinking about it now. It annoyed him as well that Mr. Mirchandani had mentioned the espresso machine, even though he knew that Mr. Mirchandani was only trying to help out, take up the cause, join the chorus of those who did not want to see Brokeland die. There was no mistaking the fact that Nat was on high simmer today, perhaps two bubbles away from a full-on roll.

“Gentlemen.”

It was a mild voice, the voice of a man trained to extol the highest in men and women while seeing them at their lowest. Trained to seemliness, to keeping itself soft and low under the pall of remembrance and grief that forever hung over Flowers & Sons. At the sound of that funereal voice, its head cocked in Singletary’s direction, the African grey parrot began to give out, note-perfect, Cochise Jones’s reading of the old Mahalia Jackson spiritual “Trouble of the World,” found on Mr. Jones’s only album as a bandleader, Redbonin’ (CTI, 1973).

“Look out,” Mr. Jones said, but as usual, Fifty-Eight was way ahead of him.

In the shade of a wide-brimmed black hat whose vibe wavered between crime boss and Henry Fonda in Once upon a Time in the West, pin-striped gray-on-charcoal three-piece, black wing tips shined till they shed a perceptible halo, Chan Flowers came into the store. Slid himself through the front door, ineluctable as a final notice from the county. Straight-backed, barrel-chested, bowlegged. A model of probity, a steady hand to reassure the grieving, a sober man—a grave man—solid as the pillar of a tomb. A good dose of gangster to the hat to let you know the councilman played his politics old-school, with a shovel in the dark of the moon. Plus that touch of Tombstone, of Gothic western undertaker, like maybe sometimes when the moon was full and Flowers & Sons stood empty and dark but for the vigil lights, Chan Flowers might up and straddle a coffin, ride it like a bronco.

“Looks like we have ourselves the hard core here today,” he said, quickly tallying the faces at the counter before settling on Archy, a question in his eyes, something he wanted to know. “Wait out here,” he told his nephews.

The two Flowers nephews stayed out on the sidewalk. Like all of Mr. Flowers’s younger crop of nephews, they seemed not to be wearing their ill-fitting black suits so much as to be squatting inside them until some less embarrassing habitation came along. They had the solemn faces of practical jokers waiting to spring a gag. One of them took out a book of Japanese math puzzles and started working them with a stub of pencil.

“Mr. Jones!” Flowers said, starting in, with that politician resolve, to fill the boxes of this human sudoku.

“Your Honor,” said Cochise Jones.

Flowers reached for Mr. Jones’s octave-and-a-half hand, its nails like chips of piano ivory.

“The honor is indeed mine,” Flowers said, “as always, to bask in the reflected luster of the legacy you represent. Inventor of the musical styling known as Brokeland Creole.” Mr. Jones was also, as far as Archy knew, the first person to use the term Brokeland to describe this neighborhood, the ragged fault where the urban plates of Berkeley and Oakland subducted. “Hello, Fifty-Eight.”

There was a silence. The bird regarded Flowers.

“Say hello,” Mr. Jones said.

“Say hello, you little jive-ass motherfucker,” Fifty-Eight said.

The voice was that of Cochise Jones, the unmistakable smoker’s croak, but way more irritable than Archy had ever heard Mr. Jones become. Everybody laughed except Chan Flowers. His eyes kept aloof from the smile on his lips.

“Keep it up,” Flowers told Fifty-Eight. “You know I have a deluxe cherrywood pet casket sitting on my stockroom shelf right now, waiting to house your remains.”

This was true; Cochise Jones had made funeral arrangements of Egyptian exactitude for himself and his partner in solitude.

“Brother Singletary.” Flowers pointed a slender finger. “The King of Bling, how are you, sir?”

“Councilman,” Singletary said, looking at Flowers the same way he looked at Fifty-Eight, with a mix of curiosity and distaste, as if touching his tongue to something bitter at the corner of his mouth.

The two of them, Singletary and Flowers, had beefed often and openly over the years, always in a civilized way. Lawsuits, real estate, a long cold war fought against a backdrop of redevelopment money using proxies and attorneys. West Oakland rumor traced the source of beef to the late 1970s, tendering the story that Singletary had married his wife out from under a preexisting condition of Chan Flowers. Rumor further added the dubious yet somehow creditable information that her reason for choosing Singletary over Flowers came down to an ineradicable odor of putrefaction on the undertaker’s hands. “I’m all right, ’less you here to tell me otherwise.”

“Now, you know,” Flowers said, half addressing the room, the voice modulated, genial, but not, in spite of the rhetoric, orotund. Cool and dispassionate, as ready to express disappointment as flattery. “Back in the Bible, only a king could even wear the bling. They did not call it that, of course, did they, Mr. Oberstein? King Solomon, in his book of Ecclesiastes, do you know the vernacular he employed to allude to that which we now style ‘bling’?”

Moby guessed, “Frankincense and myrrh?”

“He called it vanity,” said the King of Bling. “And I got no argument against that.”

“Well, that’s fine, because I did not come in here looking for an argument,” Flowers said. “Mr. S. S. Mirchandani, a latecomer to these shores, but wasting no time.”

“Councilman Flowers.”

“Good for you, sir. And Mr. Oberstein . . .”

Flowers frowned at the whale attorney, plainly searching for the kind of fitting summary he liked to bestow on people, an epitaph for every headstone.

“‘Keepin it real,’” Nat suggested.

“No doubt,” said Moby, beaming. “True dat.”

“Mr. Jaffe,” Flowers concluded. He pressed his lips very thin.

“Councilman.”

A silence followed, deeper and more awkward than it might have been because Archy had forgotten to turn over the record on the turntable. It was rare, very rare, to see Flowers at a loss for words. Was there guilt on his conscience over changing his mind about the Dogpile deal? Had he come in, this lunchtime, manned up to break the bad news himself? Or was he so caught up in running his own big-time playbook, in setting up his line to defend against the scramble, that he’d forgotten he might run into some resistance at the front counter of Brokeland?

“Archy Stallings,” Flowers said, and Archy, confused, knowing he probably should play it cold and hostile with Chan Flowers but in the lifelong habit of looking up to the man, gave himself up to a dap and a bro hug with the councilman.

“Your dad around?” Flowers said, not quite whispering but nearly so.

Archy drew back, but before he could do anything more than squint and look puzzled, Flowers had his answer and was moving on.

“I seem to remember,” he said, letting go of Archy, “somebody telling me you had left a message for me, Mr. Jaffe. At my office, not very long ago. Thought I would stop in and inquire as to what it might have been regarding.”

“Probably did,” Nat said, still without looking up. At times his protean hum took the form of an earful poured into the councilman’s office answering machine or, when possible, directly into the ear of one of his nephews, assistants, office managers, press secretaries, Nat complaining about this, that, or the other thing, trash pickup, panhandlers, somebody going around doing stickups in broad daylight. “Huh.” He feigned an effort to remember the reason for his most recent call, feigned giving up. “Can’t help you.”

“Huh,” the councilman repeated, and there was another silence. Awkward turtle, Julie Jaffe would have declared if he had been present, making a turtle out of his stacked hands, paddling with his thumbs.

“Now, hold on! Look here!” Flowers noted the baby, who had fallen asleep on the bottle. His eyes went to Archy with unfeigned warmth but flawed mathematics. “Is that the little Stallings?”

Flowers reached out his hand for a standard shake, and Archy took it with a sense of dread, as if this really were his baby and all his impotencies and unfitnesses would stand revealed.

“I know it might seem impossible,” said Flowers, holding on to Archy’s hand, still working the room, “but I remember when you were that size.” Everybody laughed dutifully but sincerely at the idea of Archy’s ever having been so small. “Child looks just like you, too.”

“Oh, no,” Archy said. “No, that is Aisha English’s baby. Rolando. Mr. Singletary’s grandson. My wife and I got like a month to go. Nah, I’m just babysitting.”

“Archy is practicing,” Mr. Mirchandani said.

“It is never too early to start,” Flowers said. Though well provided with nephews and nieces, little shorties all the way up to grown men who had played football with Archy in high school, Flowers was a bachelor and, like Mr. Jones, had no children of his own. “It can definitely sneak up on a man.”

“Maybe I should start practicing being dead,” Nat said too loudly, though whether the excess volume was deliberate or involuntary, Archy could not have said. Before any of them had the chance to fully ponder the import of this remark, Nat added, “Oh, yeah. I do remember why I called, Councilman. It was to ask you to come on by and slit my throat.”

Flowers turned, taken mildly aback. Smiled, shook his head. “Brother Nat, I will never tire of your sparkling repartee,” he said. “What a treat it is.”

“Also, I have that Sun Ra you were looking for,” Nat said, banking the anger, using his smile like a valve to feed it nourishing jets of air. “I don’t know, maybe you want to wait and pick it up at that new Dogpile store of yours. I hear their used-wax department is going to be straight-up bangin.”

“Nat,” Archy said.

“Duly noted,” Nat replied without missing a beat. “Warn me again in twenty seconds, okay?”

“I can certainly understand your distress at the possibility of the level of competition you are going to be facing, Brother Nat,” Flowers said with perfect sympathy. “But come on, man. Show some faith in your partner and yourself! What’s with the defeatist attitude? Maybe you want to consider the possibility your anxiety might be premature.”

“I have never actually experienced anxiety that turned out to be premature,” Nat said, always happy to keep punching in the clinch. “It usually shows up right on time, in my experience.”

“Just this once, then,” Flowers suggested. Itching to get out, tugging at the lapels of his jacket. “Premature.”