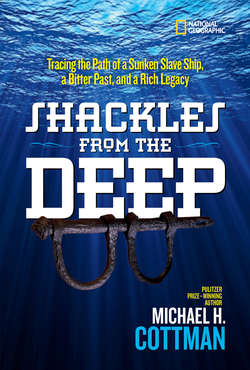

Читать книгу Shackles From the Deep: Tracing the Path of a Sunken Slave Ship, a Bitter Past, and a Rich Legacy - Michael Cottman - Страница 14

CHAPTER 3

Оглавление

The future emerges from the past. ∼ Senegalese proverb

WHAT IS

KNOWN AS

THE transatlantic slave trade began in 1441, according to historians, when two Portuguese ships sailed the coast of West Africa. They were looking for gold and other goods in Africa. But they discovered that slavery, the buying and selling of people, could be profitable as well. They knew there was a demand for workers to harvest plantations in the Caribbean and to serve as laborers in Europe and South America.

What began as trading for a few African people ultimately evolved into the centuries-long global kidnapping and exploitation of the West African civilization by European nations, including Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands. By the start of the 16th century, according to some historians, tens of thousands of African people had been transported to Europe and islands in the Atlantic Ocean. They were chained inside jam-packed slave ships and would never see Africa—their homeland—again.

The seed of fear was sowed into the fabric of the once vibrant West African villages, generations of African families were torn apart, and life for African men, women, and children would never be the same.

I didn’t know it at the time, but present-day marine archaeologist David Moore was studying the slave trade and had gotten wind of the English Wreck. Because so many shackles were found underwater in a single location, David suspected, like Moe, that New Ground Reef might be the site of a shipwreck that had been part of the 17th-century transatlantic slave trade.

Ten years had passed since Moe Molinar had discovered the shackles from the English Wreck. David was surprised that no one had yet examined the shackles. They felt it was an injustice to let those relics be forgotten and fade away like something swept beneath the carpet of time and history.

He took on a mission to learn everything he could about the English Wreck. He was beginning an amazing journey, and little did I know that I would soon be part of it. David and I believed that to understand our past—the people, cultures, and rationale for slavery—is to also understand ourselves. And so, in some ways, to David archaeology is also about the future and learning from our mistakes.

But David needed more information—a name, a date, a timeline—anything solid that could help him trace the origin of this shipwreck.

For that, David would need to strap on his wet suit and do a little underwater detective work.

BY THE START OF THE 16TH CENTURY, ACCORDING TO SOME HISTORIANS, TENS OF THOUSANDS OF AFRICAN PEOPLE HAD BEEN TRANSPORTED TO EUROPE AND ISLANDS IN THE ATLANTIC OCEAN.