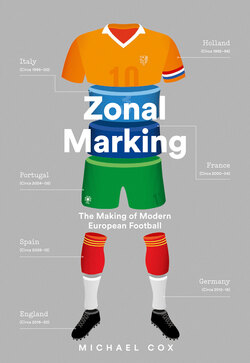

Читать книгу Zonal Marking - Michael Cox - Страница 8

2 Space

ОглавлениеThe Netherlands, by its very nature, is based around the concept of space. A country whose name literally means ‘lower countries’ is a remarkable construct, gradually reclaimed from the sea through the revolutionary use of dikes. Seventeen per cent of the Netherlands’ landmass should be underwater, and only around 50 per cent of the country is more than one metre above sea level.

The Netherlands is also Europe’s most densely populated major country (excluding small countries such as Malta, San Marino and Monaco) and worldwide of countries with similar-sized or larger populations only South Korea, Bangladesh and Taiwan boast higher population densities. The history of the Netherlands has therefore been about increasing the perimeters of the nation, and then desperately trying to find space within those perimeters.

This is, of course, reflected in Dutch football. It’s through the prism of the country’s geography that David Winner explains Total Football in his seminal book Brilliant Orange. ‘Total Football was built on a new theory of flexible space,’ he begins. ‘Just as Cornelis Lely in the nineteenth century conceived and exercised the idea of creating new polders, so Rinus Michels and Johan Cruyff exploited the capacities of a new breed of players to change the dimensions of the football pitch.’

It was Michels who introduced the ideas, and Cruyff who both epitomised them and explained them most poetically. He outlined the importance of space in two separate situations: with possession and without possession. ‘Michels left an indelible mark on how I understood the game,’ Cruyff said. ‘When you’ve got possession of the ball, you have to ensure that you have as much space as possible, and when you lose the ball you must minimise the space your opponent has. In fact, everything in football is a function of distance.’ This became the default Dutch footballing mentality, ensuring everything was considered in terms of positioning and shape. Some nations considered the characteristics of footballers most important (‘strong and fast’), some focused on specific type of events (‘win fifty–fifty balls’), others only considered what to do with the ball (‘get it forward quickly’). But, from the Total Football era onwards, Dutch football was about space, and gradually other European nations copied the Dutch approach.

Michels considered Total Football to be about two separate things: position-switching and pressing. At Ajax, the latter was inspired by Johan Neeskens’ aggressive man-marking of the opposition playmaker, combined with Velibor Vasović, the defensive leader, ordering the backline higher to catch the opposition offside. It became the defining feature of the Dutch side at the 1974 World Cup.

‘The main aim of pressure football, “the hunt”, was regaining possession as soon as possible after the ball was lost in the opponents’ half,’ Michels explained. ‘The “trapping” of the opponents is only possible when all the lines are pushed up and play close together.’ Holland’s offside trap under Michels was astounding, with the entire side charging at the opposition in one movement, catching five or six opponents offside simultaneously, before interpretations around who exactly was ‘interfering with play’ made such an extreme approach more dangerous in later years.

This tinkering with the offside law notwithstanding, pressing remained particularly important for Cruyff and Louis van Gaal during the era of Dutch dominance, with both managers encouraging their players to maintain an extremely aggressive defensive line and to close down from the front. Cruyff’s Barcelona and Van Gaal’s Ajax dictated the active playing area, boxing the opposition into their own half and using converted midfielders in defence because they spent the game close to the halfway line.

‘I like to turn traditional thinking on its head, by telling the striker that he’s the first defender,’ Cruyff outlined. ‘And by explaining to the defenders that they determine the length of the playing area, based on the understanding that the distances between the banks of players can never be more than 10–15 metres. And everyone had to be aware that space had to be created when they got possession, and that without the ball they had to play tighter.’

Van Gaal’s approach was similar, with speedy defenders playing a high defensive line, and intense pressing in the opposition half. ‘The Ajax number 10 is Jari Litmanen, and he has to set the example by pressuring his opponent. Just compare that with the playmaker of ten years ago!’

The best representation of the Dutch emphasis on space, however, was in terms of the formations used by Cruyff’s Barcelona, Van Gaal’s Ajax and the Dutch national team. The classic Dutch shape was 4–3–3, although in practice this took two very separate forms.

The modern interpretation of 4–3–3, epitomised by Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona, prescribes one holding midfielder behind two others, effectively a 4–1–2–3; the Dutch would often flip the triangle, creating a 4–2–1–3, but would still consider this a 4–3–3. Nowadays it seems curious that the two can be conflated, especially considering this is essentially the difference between 4–3–3 and 4–2–3–1 formations, the two dominant shapes of the 2010s. But during this earlier period, 4–3–3 was a philosophy as much as a system, and with other major European countries generally preferring boxy 4–4–2 systems or sometimes a defensive-minded 5–3–2, the concept of a three-man attack spread across the field was in itself audacious. The precise positioning of the midfielders was a minor detail.

But both Cruyff and Van Gaal became even bolder. Upon his appointment at Ajax, Cruyff reduced the four-man defence to a three-man defence, explaining that the majority of Eredivisie sides played two up front, and therefore a trio of defenders could cope. He effectively replaced a defender with a number 10, forming a diamond midfield between the three forwards and three defenders. This was the Dutch 3–4–3, which was very different from the Italian-style 3–4–3 with wing-backs that would later be popularised, for example, by Antonio Conte at Chelsea. Cruyff’s holding player would move between defence and midfield, and the number 10 would move between midfield and attack, with two box-to-box players either side. ‘Cruyff put up with the risks connected to this decision,’ Michels outlined. ‘The success of the 3–4–3 is dependent upon the individual excellence that serves this spectacular but risky style of play … it places high demands on the tactical cohesion of the central players, and it demands that they have a high level of football intelligence.’

Van Gaal disagreed with Cruyff on many topics, but he largely followed Cruyff’s basic formation, using 3–4–3 throughout his tenure at Ajax. Michels, Cruyff’s old mentor, was himself a convert and utilised the system when taking charge of the Dutch national side at Euro 92, although he considered 3–4–3 a mere variation on his old 4–3–3. At this tournament, the uniqueness and fluidity of the Dutch shape confused foreign observers, and the same system was described as, variously, 4–3–3, 3–4–3 and even 3–3–4, a notation that looks absolutely ludicrous on paper compared with the dominant 4–4–2 and 5–3–2 systems of the time, but shows how the Dutch were thinking about the game in an entirely different manner to German, Italian and Scandinavian sides.

The crucial, non-negotiable element of these systems was width. Regardless of the number of defenders, the tilt of the midfield or whether or not the centre-forward was supported by a number 10, Dutch coaches insisted on two touchline-hugging, chalk-on-the-boots wingers. Again, this was unfashionable at the time, with the 4–4–2 system requiring midfielders who tucked inside, and the 5–3–2 relying on overlapping runs from wing-backs to provide width. The Dutch, though, intrinsically believed in the importance of stretching play and prising the opposition defence apart to create gaps for others. Michels spoke about the importance of using ‘true flank players who have great speed and good skills … they must be selected and trained at a very young age,’ he said. ‘The Netherlands is one of few countries that actually develop this kind of player in the 4–3–3 system.’

Van Gaal’s 1992 UEFA Cup-winning side depended on right-winger John van ’t Schip, a classic old-school winger who boasted the three classic qualities: a turn of speed, a drop of the shoulder and a good cross. Van ’t Schip would never receive the ball between the lines, nor would he cut inside; he was a winger and stayed on the touchline. Left-sided Bryan Roy was similar, albeit quicker and less of a crosser. He was supposed to perform an identical task to Van ’t Schip, although he infuriated Van Gaal by drifting inside too frequently. The contrast in systems in their 1992 UEFA Cup Final victory against Torino was particularly stark: the Italian side played 5–3–2, the Dutch played 3–4–3.

Roy also played wide-left for Michels’ Netherlands side at Euro 92, although the right-winger was Ruud Gullit, an atypical player for this system, essentially a central player that had to be accommodated somewhere because he was too important to omit. By the 1994 World Cup the Dutch were coached by Dick Advocaat, who continued with Roy but also discovered the exciting Gaston Taument – and, more significantly, Ajax’s Marc Overmars.

Overmars was the most typical, and most accomplished, Dutch winger of this period. He offered searing acceleration, was happy on either flank because of his two-footedness, loved riding a tackle, and could cross and shoot excellently. He was exciting yet efficient, a winger based around end product rather than trickery, which made him perfect for Van Gaal.

‘I was a coach who wanted to attack with wingers – there aren’t a lot of good wingers around, and Overmars was one of the best,’ remembered Van Gaal. ‘He was a good dribbler who could beat people one-on-one and that was important for a winger in our system, but he also had a very good assist record and he could score goals. Every season he got 10–15 goals and they were nearly always important goals. We need his kind of player to maintain the game as an attractive spectacle.’ If Van Gaal could have fielded two Overmarses, one on either flank, he would have. Instead, he fielded him wide-left, and the speedy Nigerian Finidi George on the opposite flank.

The curious thing about Van Gaal’s use of wingers, however, was that they were almost decoys, part of the overall framework rather than star performers. Something similar can be observed of the centre-forwards: the likes of Stefan Pettersson and Ronald de Boer (who was also used as a midfielder) were tasked with leading the line rather than dominating the goalscoring, instructed to stretch play and occupy opposition centre-backs. Van Gaal’s reasoning was simple: if the wingers dragged the opposition full-backs wider, and the centre-forward forced the opposition centre-backs backwards, it would create more space for the star – the number 10.

For both Ajax and Holland during this period, that meant one man: Dennis Bergkamp. While not necessarily the best Dutch footballer of this period – Marco van Basten won the Ballon d’Or in 1992, while Bergkamp came third and then second in 1993 – he was certainly the most typically Dutch footballer of the 1990s, because his entire mentality was based around that familiar concept. ‘On the field, my greatest quality was seeing where the space was, and knowing where you can create space,’ he explained. Throughout his autobiography, Bergkamp explains everything about his game, and everything about his career path, with the same word: space. Why was he so obsessed with scoring chips? ‘It’s the best way – there’s a lot of space above the goalkeeper.’ Why did he struggle to connect with his Inter Milan teammates during his spell in Serie A? ‘There was a huge space between us, and it was dead space.’ Why did he transfer to the Premier League? ‘I knew you could get space in England.’ What was the key to his legendary 1998 World Cup winner against Argentina? ‘It was a question of creating that little space.’ And, even, what did he dislike so much about aeroplanes? ‘There was hardly any space – it was so cramped it made me claustrophobic.’

Bergkamp was an Amsterdammer who had risen through Ajax’s academy, although his journey to becoming the club’s number 10 was curious. As a teenager he was considered a pure centre-forward, and initially appeared under Cruyff in 1986/87 as a right-winger. ‘Wingers played a simpler game back then,’ Bergkamp recalled, confirming the accepted manner of wing play at the time. ‘You weren’t expected to get into the box and shoot – you had to stay wide, feel the chalk of the touchline under your boots. Your job was to stretch their defence, get past your man at speed and cross the ball.’

After Cruyff’s departure, Bergkamp was demoted to the B-team by Kurt Linder, a German coach who didn’t understand the Dutch mentality and preferred a rigid 4–4–2. In Ajax’s reserves, however, Bergkamp played under Van Gaal, who recognised his talent and fielded him as the number 10. When Linder was dismissed, Antoine Kohn became caretaker manager, but it was Van Gaal, now his assistant, who was in charge of tactics. Van Gaal insisted on fielding Bergkamp in the number 10 role, which prompted Bergkamp to set a new Eredivisie record by scoring in ten consecutive matches. When Leo Beenhakker was appointed first-team manager, however, he misused Bergkamp, deploying him up front or out wide again. It took the appointment of Van Gaal as manager, in 1991, for Bergkamp to regain his rightful position. The Dutch press were so captivated by Bergkamp’s performances in the number 10 role that they felt compelled to invent a new term for it: schaduwspits, the ‘shadow striker’.

In that role Bergkamp was sensational. At Ajax he developed an excellent partnership with Swedish centre-forward Pettersson, a more conventional forward who also made intelligent runs to create space for him. During this period Bergkamp won three consecutive Eredivisie top goalscorer awards, jointly with Romario in 1990/91, then outright in the following two seasons, despite not being a number 9 – or, in Dutch terms, precisely because he wasn’t a number 9. Cruyff is the obvious example of a prolific forward who dropped deep rather than remaining in the box, but the Eredivisie’s all-time top goalscorer – Willy van der Kuijlen – was also a second striker, not a number 9. Van der Kuijlen, who spent nearly his entire career with PSV, had the misfortunate to be playing in the same era as Cruyff, and squabbles between Ajax and PSV players meant he was underused at international level. But in the Eredivisie he was prolific, and formed a partnership with Swedish number 9 Ralf Edström that was identical in terms of nationalities and style to Bergkamp and Pettersson’s relationship two decades later: the Swede as the target man, the Dutchman as the deeper-lying but prolific second striker.

That was the Dutch way: the number 9 sacrificing himself for the number 10, and this arrangement continued at international level, despite the fact that Holland’s striker was the wonderful Van Basten. At Euro 92, when Holland sparkled before losing to Denmark in the semi-final, their best performance was a famous 3–1 thrashing of fierce rivals Germany. Their third goal was significant: midfielder Aron Winter attacked down the right and assessed his crossing options. Van Basten was charging into the penalty box, seemingly ready to convert a near-post cross. But when Winter looked up, Van Basten had just glanced over his shoulder, checking Bergkamp was in support. He was. So, while occupying both German centre-backs and sprinting frantically to get across the near post, Van Basten threw out his right arm and pointed behind him, towards his strike partner. Winter saw Van Basten’s signal and chipped a pull-back behind him, towards Bergkamp, who neatly headed into the far corner. It was the most fantastic example of the Dutch number 9 creating space for the Dutch number 10.

Bergkamp was the tournament’s joint-top goalscorer, while Van Basten finished goalless but was widely praised for his selflessness, and both were selected in UEFA’s XI of the tournament. Their partnership worked brilliantly. ‘Marco was a killer, a real goalscorer, always at the front of the attack – whereas I was more of an “incoming” striker,’ Bergkamp said. ‘If records had been kept they’d show how often Marco scored from ten yards or less. For me, it was from about 15 yards.’

Bergkamp had a curious relationship with Van Gaal, who had initially shown tremendous faith in him, ‘inventing’ his shadow striker role. When Bergkamp missed the second leg of Ajax’s victorious UEFA Cup Final against Torino because of flu, Ajax’s celebratory bus parade detoured to take the trophy past his apartment, and at the reception Van Gaal took the microphone and bellowed Bergkamp’s name from the balcony of the Stadsschouwburg Theatre to the assembled masses below, who responded with their biggest cheer of the day. But the two constantly quarrelled in Bergkamp’s final season at Ajax in 1992/93, before his move to Italy. Having already announced his intention to leave, Bergkamp’s performances were criticised by Van Gaal, who substituted him at crucial moments when Ajax needed goals to keep their title bid alive. In Van Gaal’s opinion, Bergkamp had become too big for his boots. By treating him harshly, he sent a message to Ajax’s emerging generation that superstars would not be tolerated – the team, and the overall system, were far more important.

Bergkamp endured two unhappy seasons at Inter, before becoming the catalyst for Arsenal’s evolution into the Premier League’s great entertainers. The reason for his failure in Italy, and his unquestionable success in England, was inevitably about the amount of space he was afforded. ‘English defences always played a back four, with one line, which meant they had to defend the space behind,’ he said. ‘In Italy they had the libero, but the English had two central defenders against two strikers, so they couldn’t really cover each other. As an attacker I liked that because it meant you could play between the lines.’ From that zone, Bergkamp became the Premier League’s most revered deep-lying forward, although he became more prolific in terms of assists than goals.

Ajax, however, didn’t desperately miss him. In Bergkamp’s three seasons as Eredivise top goalscorer, Ajax didn’t win the title – PSV triumphed twice and Feyenoord once – but in the three seasons after his departure, Ajax won three in a row, while winning the Champions League in 1995 and reaching the final the following year. This wasn’t solely down to Bergkamp’s departure, of course, and more about Ajax’s emerging generation of players. It helped, however, that Bergkamp was replaced by an equally wonderful talent, the Finnish number 10 Jari Litmanen. ‘Dennis Bergkamp was brilliant for Ajax, but the best number 10 we have ever had was Jari,’ said Frank Rijkaard. Litmanen was Finnish rather than Dutch, and therefore his qualities are less salient here, but he perfectly encapsulated the Ajax idea of a number 10. He was excellent at finding space, had a wonderful first touch and could play the ball expertly with either foot. Van Gaal said that whereas Bergkamp was a second striker, Litmanen was the fourth midfielder.

After his retirement, when asked to name his ‘perfect XI’ of past teammates by FourFourTwo magazine, Litmanen spent two days mulling over his options – Ballon d’Or winners like Luís Figo, Michael Owen and Rivaldo, and other world-class options like Michael Laudrup, Steven Gerrard, Zlatan Ibrahimović and Pep Guardiola – before simply naming the entire 1995 Ajax side. That underlined the harmony of Van Gaal’s Champions League winners; Litmanen didn’t want to upgrade in terms of individuals, because the collective might suffer.

1994/95 was an extraordinary campaign for Ajax; not only did they lift Europe’s most prestigious club trophy, they also won the Eredivisie undefeated. Van Gaal counted on a sensational generation of talent, but also created the most structured, organised side of this era.

Tactical organisation, at this point, was often only considered an important concept without the ball; teams defended as a unit, while attackers were allowed freedom to roam. But Van Gaal was obsessed with structure within possession, almost robbing his attacking weapons of any spontaneity. The crucial difference between Van Gaal’s system and the approach of his predecessors Michels and Cruyff was that Van Gaal effectively prohibited the classic position-switching up and down the flanks, the hallmark of Total Football. Previously, Ajax’s right-back, right-midfielder and right-winger, for example, would often appear in each other’s roles, but Van Gaal ordered his midfielders to stay behind the wingers; not because he didn’t subscribe to the concept of universality, but because it harmed the side’s structure. Ajax were supposed to occupy space evenly, efficiently and according to Van Gaal’s pre-determined directions. ‘Lots of coaches devote their time to wondering how their players can do a lot of running during a match,’ he guffawed. ‘Ajax trains its players to run as little as possible on the field, and that is why positional games are always central to Ajax’s training sessions.’

The classic starting XI featured Edwin van der Sar in goal, behind a three-man defence of Michael Reiziger, Danny Blind and Frank de Boer, three technical, ball-playing defenders. Ahead of them was Frank Rijkaard, an exceptional all-rounder who played partly in defence and partly in midfield, allowing Ajax to shift between a back three and a back four. The midfielders on either side of the diamond were the dreadlocked, Suriname-born duo of Clarence Seedorf and Edgar Davids. They were both technically excellent but also energetic enough to battle in midfield before pushing forward to support the central attackers rather than the wingers, Finidi George and Marc Overmars, who were left alone to isolate opposition full-backs. Then Litmanen would play between the lines, dropping deep to overload midfield before motoring into the box to support Ajax’s forward, generally Ronald de Boer, although he could play in midfield with Patrick Kluivert or Nwankwo Kanu up front.

Ajax’s 1995 side is certainly comparable to Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona side a decade and a half later – possession-based, tactically flexible, adept at pressing – but whereas Barca attempted to score following intricate passing combinations through the centre, many of Ajax’s goals were much simpler. The midfielders would service the wingers, who would dribble past the opposition full-backs and cross for the forwards. When Ajax were faced with a deep defence, the most fundamental part of their possession play involved building an attack on one flank, realising they were unable to get the nearest winger in a one-against-one situation, so quickly switching play to the opposite flank, where there would be more space, to try the other winger. This was generally achieved with two or three quick passes flowing through Davids, Rijkaard and Seedorf, rather than with a long crossfield ball. This way, opponents were momentarily drawn towards those central midfielders, which allowed the opposite winger a little extra space.

Ajax’s crowning moment was the 1995 Champions League Final victory over Fabio Capello’s AC Milan. While Capello almost always selected a 4–4–2 formation, for the final he narrowed his midfield quartet to help compete with Ajax’s diamond. Capello tasked his creative number 10, Zvonimir Boban, with nullifying Rijkaard before dropping back towards the left, while defensive midfielder Marcel Desailly performed a man-marking job on Litmanen. With hard-working forwards Marco Simone and Daniele Massaro cleverly positioning themselves to prevent Blind and De Boer enjoying time on the ball, and therefore directing passes to the less talented Reiziger, Ajax struggled before half-time.

After the break Van Gaal made three crucial changes that stretched the usually ultra-compact Milan, allowing Ajax extra space. First, Rijkaard was instructed to drop back into defence, in the knowledge that Milan’s midfielders wouldn’t advance high enough to close him down. Rijkaard started dictating play. Second, Van Gaal withdrew Seedorf, shifted centre-forward Ronald de Boer into a midfield role, and introduced Kanu, whose speed frightened Milan’s defence and forced them to drop deeper. Third, he added yet more speed up front by sacrificing Litmanen, widely considered Ajax’s best player, and introducing the extremely quick 18-year-old Patrick Kluivert.

In typical Dutch fashion, Ajax had increased the active playing area by tempting Milan’s attack higher and forcing their defence deeper, thereby giving themselves more space in midfield. The winner came five minutes from full-time, with substitute Kluivert exploiting Milan’s uncoordinated defensive line and poking home after Rijkaard had assisted him from the edge of the box. That might sound peculiar: Ajax’s holding midfielder, who had been told to drop into defence, playing the decisive pass from inside the final third. Defenders showcasing their technical skill, however, was another key feature of Dutch football during this period.