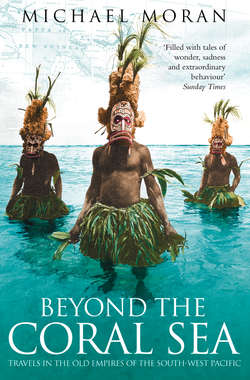

Читать книгу Beyond the Coral Sea: Travels in the Old Empires of the South-West Pacific - Michael Moran - Страница 11

4. Death is Lighter than a Feather

ОглавлениеAcross the sea,

Corpses in the water,

Across the mountains,

Corpses heaped up in the field,

I shall die only for the Emperor,

I shall never look back.

Japanese Second World War Poem

No roads link Alotau, the provincial capital of Milne Bay Province, with Port Moresby. Boats are infrequent and no longer run to schedule. Fortunately, this has insulated the province from raskol activity which blights life in the Highlands. The relative isolation of Alotau meant that flying from Port Moresby was the only feasible alternative.

The ‘Islander’ light aircraft climbed laboriously out of barren Jacksons airport over the forbidding green of the Owen Stanley Ranges. A gothic landscape unfolded below, the precipitous ranges and valleys resembling the spires and flying buttresses of monumental medieval cathedrals draped in cloaks of thick, tropical vegetation. The gloom and mystery brought to mind the inconceivable hardships endured by nineteenth-century explorers who attempted to probe the interior of New Guinea from Port Moresby. Precipitous paths needed to be cut through thick jungle slowing progress to a mile a day. Sir William MacGregor, first Lieutenant-Governor and intrepid explorer, wrote in his diary of the ‘deathlike stillness’ that prevailed in the dripping fog that swirled about the moss-covered trees as he climbed Mount Victoria. Gurney airport, which services Alotau, occupies the same position it did in 1942. Charles Gurney was one of the colourful band of aviators who opened up New Guinea in the 1930s and was a squadron leader in the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force). Below the spinning hub of the propeller, endless plantations of oil-palm unrolled sporadically through breaks in the low cloud.

The terminal was the usual fibro affair with slowly circulating ceiling fans. My luggage was quickly unloaded and packed into a truck. The road into town was severely potholed, with river fords constructed of shattered blocks of concrete. Torrents rushed across them into Milne Bay, threatening to sweep us away. It was hot and uncomfortably humid. Luxuriant vegetation swathed in mist fell like velvet curtains from the ranges lowering into the Coral Sea. The province showed little sign of development.

This formidably rich cultural area is known by Europeans as the Massim. The inhabitants speak Austronesian languages, unlike the majority of Papua New Guineans, who speak one or other of the 300 Papuan languages. Much of the Milne Bay Province consists of islands and the finely-carved artefacts reflect this marine environment. Spectacular ornamented canoes, weapons of ebony and black palm, red spondylus shell necklaces and armshells of tangled beauty, clay pots of abstract shape, and noble war shields are the legacy of the past. Gifted master carvers worked along this coast in the nineteenth century, but the production of such masterpieces has tragically declined in modern times. The culture of the north supports large village communities, whereas in the south, clusters of tiny hamlets nestle along the shore. Their belief in sorcery and magic is strong. Compulsive sweeping keeps the villages free of any personal waste that a sorcerer might fix upon and use in casting an evil spell.

Massim communities are composed of clans ruled by symbolic totems representing an animal, bird, fish or plant. Children take the totem of their mother and it is forbidden for members of the same totem to marry or have sexual relations. In the past the punishment for illicit sex was death. In the almost complete absence of tourism, apart from hermetic groups of divers, the people subsist through fishing and agriculture. Crocodiles and turtles, pigs and megapodes (a small, dark-feathered scrub fowl), bananas and coconuts are being insidiously supplanted by modern supermarket foods, particularly cheap tinned meat like Spam that has scarcely altered since it sustained troops in the Second World War.

The Massim was one of the first areas of New Guinea evangelised by British missionaries in the late nineteenth century. The local people’s profound belief in the power of magic posed the greatest challenge to Christian conversion. The villagers continue to believe that supernatural spirits inhabit trees, streams, rocky places and swamps. Belief in Jesus has not removed the fear of sorcerers who kill by projecting fatal diseases and cannibalistic flying witches that become airborne after dark, snapping bones and tearing entrails. More seductively, erotic magic weaves love spells with flowers plucked in secret groves. More optimistically, a happy life after death is guaranteed by a magic that promises three states of Paradise and an afterlife where Hell is sensibly absent.

Alotau developed from the original Second World War American military base, but the capital was transferred officially from Samarai Island only in 1968. This islet, lying off the easternmost point of the mainland, had become inconvenient as it was only accessible by sea and overcrowded with residents. Alotau has the reputation of being the safest town in Papua New Guinea, a reputation jealously guarded by the inhabitants.

I had arrived in the sultriness of mid-afternoon. Hundreds of listless people were sitting under the rain trees in the shade cast by the awnings of prefabricated supermarkets. They were almost motionless in the oven-like conditions and appeared to be in shock, as if a terrorist bomb had recently exploded. Clumps of resentful youths were chewing buai,1 smiling women in colourful cottons suffered tugging children, a covered market baked in the heat. Banana boats skittered across the glittering harbour and rusting Taiwanese trawlers disintegrated at their moorings.

A path crossed a stream, and I climbed some steep stairs through an avenue of trees past the tables of female sellers of buai. This green globular betel nut, which is the seed of the Areca palm, is laid out in carefully measured rows and beside each nut lies a small betel-pepper stick, the fruit of the pepper vine. The husk of the Areca seed is removed and the tip of the green pepper spike dipped in lime, now usually contained in an old plastic film container. The mixture is then enthusiastically chewed. In the past the powder was taken from an attractive gourd or the shell of the young coconut, often decorated with intricate burnt-in designs and fitted with a woven or wooden stopper. A beautifully carved ebony spatula with a pig or human carved on the handle would be used to remove the lime. Some spatulas were made from the bones of relatives. The family would then be able to suck the bone when taking lime as an intimate reminder of the departed. Lime powder is no longer made from crushed coral by women in secret locations. Spatulas are seldom used.

Gallons of saliva are generated from the chemical reaction and the resulting vermillion juice is spat in jets like an uncontrollable haemorrhage. The effect is horrifying to witness and mildly narcotic to experience. The villagers say it ‘makes them feel strong’, ‘makim head good fella’. Certainly it makes people more talkative, but excessive use creates a drugged daze in the chewer. Nuts are often presented to visitors. In the past, if the point of an offered nut faced away from the stranger, it was a secret signal to kill him.

I was overcome by nausea and an atrocious bitterness during my first attempt at ‘wearing New Guinea lipstick’ as it was popularly known. Gales of laughter accompanied my facial contortions and twitches but much friendliness followed. Captain Cayley-Webster, travelling through New Guinea in the late nineteenth century, referred to betel as ‘a veritable pâté du diable’. Chewing is paramount in social relations in Papua New Guinea, and the cosmetic clash this creates with modern sanitised life has become a symbolic focus of cultural freedom and kastom. Betel is chewed by men and women when working in the gardens, attending feasts and travelling by canoe, when making love and meeting friends. Television advertisements encourage people to stop chewing because of risks of mouth cancer and to present a ‘clean image’, but for most it is a universal refuge begun early in life, a balm to the rigours of existence in these islands.

I would be staying at Masurina1 Lodge, run by Chris Abel, grandson of the missionary Charles Abel. I had never met him, but I had read a great deal about his unique regional business. In 1973 Alotau was a tiny place consisting of five trade stores and a post office. Chris established the Alotau Tea Shop with the help of Mila Walo (‘Aunty Mila’), one of the outstanding women who emerged from Charles Abel’s Kwato Mission. This tea shop was the forerunner of a large local public company called Masurina that Chris Abel established at Milne Bay, with interests ranging from accommodation to fisheries and construction. The local people of Milne Bay are major shareholders in what has become a symbol of the commercial way forward in modern PNG. I wanted to visit Samarai Island and the Kwato Mission and talk to Chris about his controversial forebear.

‘The Lodge’, as it is known locally, is situated high above the harbour and has the flavour of an early South Seas colonial resort with prefabricated units painted with large blue numbers. Reception and what might be termed a drinks veranda have a pleasant colonial atmosphere. A number of fans were ranged along the balustrade to keep the air moving and the mosquitoes at bay. My room overlooked the last thrust of the Owen Stanley Ranges, a line of jagged peaks heading down to the sea. Coconut palms crowned the hill above my writing table and from a garden below, a disembodied, unearthly monody sung by a child floated on the breeze. A dog barked in a distant valley. The weather felt unstable, the peaks shrouded in knotted clouds that were cut by the occasional flicker of lightning followed by sombre thunder.

A couple of attractive local girls with engaging smiles were looking after reception and talking quietly in the Tavara language. A figure sat at a table drinking beer and reading. He wore olive-green officer’s fatigues as part of his tropical kit, the crown of his Australian Akubra hat covered with a colourful woollen cap from the Highlands. A furled racing umbrella was propped against the arm of the chair. Some artefacts and a slim volume entitled Betel-Chewing Equipment of East New Guinea lay on the bamboo table. Clear, grey eyes and a welcoming face framed by a well-trimmed beard greeted me as he lowered his clip file.

‘Come and sit down. Get yourself a beer.’

It was a relief to relax near regular puffs of air from the fan. Carrying my luggage the short distance to my cabin had sent the sweat streaming down my face. Any movement in this sweltering heat apart from drinking seemed excessive. I bought an ice-cold beer and sat down in a cane armchair.

‘Who do you work for?’ he asked directly. The pressing need to speak to a European faintly betrayed itself.

‘No one actually. Just wandering the islands.’

‘Really? A wanderer is pretty unusual round here. I work for AusAID – Biomedical Engineer checking equipment – at the hospital.’ He would be the first of many aid workers I would meet on my journey.

‘So, what’s the state of the hospital equipment in PNG?’ I asked, unsure whether I wanted to hear the answer. Assembling my own travelling medical kit had taken weeks of thought and terror, as the list of possible ghastly diseases and the range of conflicting advice grew.

‘Dire, absolutely dire. The hospital in Alotau though is actually quite good with excellent staff.’ There was disappointment in his voice, overlaid with an almost convincing pragmatic realism.

‘What sort of problems do they have?’

‘Well, the main problem is lack of maintenance. The cultural mentality is so different. They think sterilising only requires the instruments to be washed in Omo.’

I felt that the constant struggle with cultural ‘otherness’ had made him almost unnaturally phlegmatic. He smiled wryly.

‘Is it the same all over the country?’

‘The Highlands are worse of course. I saw an ambulance in Mendi drenched in blood. I thought, “God, it’s bloody violent. Even the ambulances are blood-soaked!” Actually, it was betel juice from people spitting on it. Looked just like blood! But spitting on an ambulance?’

I smiled but my feigned bravado concerning health matters was ebbing away. We sat in silence, the fans whirring and the occasional tortured dog screaming in agony.

‘The tribes up there are spearing each other again. They love fighting and drinking. Some died recently after downing a hellish cocktail of coconut juice, methylated spirits and turpentine. It’s reverting to pre-colonial days.’

An unmistakable tone of angry disillusionment and ruined hopes marked his voice. So many aid workers begin with high ideals that fade in the face of indigenous resistance to change. The benefits of being rushed headlong into a technological paradise from the Stone Age are not immediately obvious to men still profoundly involved with their elemental natures.

‘Don’t you ever worry you might be targeted?’

‘Sometimes, but I am related to a Napoleonic general!’

Despite the off-hand smile, an expression of cultivated stoicism hardened in his eyes. An easy man to underestimate.

‘Is that so.’ I looked away.

I must admit to being sceptical of Napoleonic references in this part of the world. I had heard many such claims while travelling through Polynesia in my younger days. Ravings mostly. The South Pacific attracts extraordinary characters often beset by cosmic visions.

Heavy tropical rain had begun to fall on the iron roof and the storm channels were brimming with water. Night was quickly closing in as the fans hummed lazily. Village girls carried platters of food into the dining room. I rolled down my sleeves – a precaution at dusk in this malarial area. The female Anopheles emerges to strike at close of day. Small, silent and deadly.

‘But you’re not French are you?’

‘No, English, actually. Born in Surabaya in Java.’

‘So who was the French general?’

‘General Alexandre Mocquery. He attended the Military School at Fontainebleau. Around 1806, I think it was.’

He chuckled in the way that those moved by the memory of illustrious relatives often do – a mixture of respect combined with a feeling of comparative inadequacy. The silhouetted coconut palms began to dissolve in sheets of water.

‘How did he die?’

‘Fever in Algeria.’

We both fell silent and looked out into the opaque, watery atmosphere, listening to the muffled clatter of a tropical deluge on the broad leaves and thought of Europe. The ghosts of a hundred misguided adventurers and metaphysical questers seemed all around us.

‘Shall we go in for dinner?’ he said at last.

Sele and two other men were standing by the roadside as the Toyota Hilux four-wheel-drive whizzed past. They were bending over, staring up and listening to a rattle in the suspension of the truck.

‘It’s not serious,’ one said.

‘It’ll get us there,’ said the other with finality.

‘Do you really think so?’ I said.

The vehicle had turned around and was steaming back down the road toward us, sitting high on its suspension. Again they bent over with ears cocked.

‘The brakes were all right last week,’ Sele said.

‘I went down to East Cape last month in it,’ another said.

‘Oh, come on! Let’s go!’ I said. The Toyota roared past once again sounding pretty rough.

Sele, myself and two laughing island girls, Rachel and Marie, loaded up with provisions and plenty of chilled water. Our excursion to East Cape, the most easterly point of Papua New Guinea, would take most of the day. The atrocious road was full of the usual potholes requiring the skills of a rally driver to negotiate. We would need to cross some fifteen rivers and streams swollen by unseasonable rain. Some had warning signs of treacherously deep water: ‘Jesus Loves Careful Drivers – Take the Right Side’. Love messages with hearts and arrows had been picked out in white shells on the river beds.

The area toward East Cape is relatively unspoilt, and we passed the immaculate hamlets, villages and family communities of the Tavara people that have been erected at the very edge of the water. Clear, swept areas of sand have been carved from the dense tropical jungle to accommodate the thatched-roof huts erected on stilts with diapered walls of palm leaf. Smaller detached huts nearby serve as kitchens. Bedding of patterned sleeping mats and pillows was laid out in the sun to air. A Milne Bay woman stood at the window waving and smiling through the brightly coloured washing hanging on the line. Beautiful children squealed with intense pleasure as the family pig blundered about the yard accompanied by a wretched dog with its scrawny pups. The road caused us to be thrown about inside the cabin like rag dolls.

‘Where were you born, Sele?’ I asked. The girls craned forward, bumping my shoulder and listening intensely to my words, collapsing in fits of giggles if I caught their eye.

‘On Logea Island, near Samarai.’

‘Really? I hope to go there. I want to visit the Kwato Mission.’ Coincidentally, we were passing a church, one of many along this road. Pale blue walls with a simple black cross. As it was Sunday, a large congregation had filled the building. The huge windows were thrown open and hymns were being sung with a passionate enthusiasm that saturated the tropical groves.

‘They are good people!’

Sele had a stained ivory smile and seemed illuminated from within by his Christianity. A good man. The girls had never been to East Cape before and were in a state of high excitement, chattering and giggling interminably.

‘Are you still at school, Rachel?’ I glanced over my shoulder at the pair bouncing in the back.

‘No!’ they chorused, ‘Mipela iwok lon Lodge, insait lon kisen.’1 Few children go on to secondary school. We bumped along, the springs often bottoming out in the potholes.

‘Is there much violence around Milne Bay, Sele?’

‘No. It’s peaceful here. A ship came in from Lae with many raskols last month. It was in the harbour. Many crimes happened but we got rid of it pretty quick. We don’t want such things here in Alotau.’

He seemed proud of taking the moral high ground and clearly wanted me to judge Milne Bay and the islands as far superior to the rest of the country.

Picturesque family groups were sitting on the beach in the shade of flowering pink and white frangipani trees, talking, laughing and looking out to sea. Many elegant canoes with outriggers were drawn up on the shore under rosewoods. The hulls had faded to a delicate pale blue or jade green. Groups of children happily played with models fitted with sails. These childish replicas were to be the only sails I saw whilst in Papua New Guinea.

The puncture we got from the brutal coral road was only to be expected. Sele showed not the slightest exasperation, treating it more as a slight inconvenience than a drama. The spare wheel was loosely chained to the vehicle and the change was accomplished in record time. The girls were extremely helpful, as I attempted to be, but the humidity and the searing sun made physical effort an exhausting task for a dimdim.1

This road had been a quagmire in 1942 when the airbase at Gili Gili was being hewn out of the jungle to defend Milne Bay against a landing by Japanese Marines. The local people had watched spellbound as gelignite was placed in holes drilled in the base of coconut palms and the detonation propelled them vertically into the air. Our situation reminded me of photographs I had seen of bogged trucks and ruptured tanks that had skidded into ditches during the battle.

During the Second World War, Milne Bay possessed great strategic significance as it guarded the sea lanes to Australia and the eastern approaches to Port Moresby. By mid-1942, the area had become enormously important to General MacArthur in his campaign against the seemingly invincible Japanese. The Imperial Army had conquered the Bismarck Archipelago and was poised to strike at Australia. Pearl Harbor, Singapore, Malaya, the Philippines and the Dutch East Indies had already been consumed by the forces of the Rising Sun. A remarkable victory was achieved here by the Australians and the Americans against malaria, typhus, bombs, scorpions, mosquitoes, rats, falling coconuts, crawling insects, green dye bleeding from their uniforms, disease, forbidding terrain, incessant rain, clinging mud and a fanatical enemy. This largely forgotten battle marked the extraordinary first defeat of the Japanese on land and halted any further advance in the Pacific, west or south.

The local villagers played a significant role in the victory and suffered terribly at the hands of the Japanese. Many village men were tied to coconut palms with signal wire and bayoneted in the chest or anus. A girl of fourteen was staked out, stripped naked, a bamboo stake driven through her chest, her breasts cut off and placed on the ground beside her. Poor food supplies meant the Japanese even turned to cannibalism. Australians took their own violent turn, and carried out summary executions of villagers they suspected of collaboration. For the local people it was a foreign war of which they understood nothing and cared less. Despite the atrocities, their loyal support of the Australians led to them being known as the ‘fuzzy wuzzy angels’.

The perpetration of unspeakable tortures by the Japanese has an explanation of sorts. The private in the Japanese army was treated as a cipher by his officers; animals and weapons were treated better. They became intoxicated in the heat of battle and disregarded discipline. Brutalised soldiers may have been effective against Russian, Chinese or Manchu troops, but permitting emotion to dominate proved fatal in the Pacific War. In the jungle they suffered from malaria, fatigue, poor food and heavy, outdated equipment. A private had no method of relieving the pressure of his pent-up fury. Japanese officers intended their men to hate them. The officer class was driven by elitism and a sense of fanatical loyalty to the Emperor and his Imperial Army. When unsheathing the sacred regimental sword, an officer would bind his mouth with cloth to avoid breathing upon it and as a war journal observes, ‘amorously caress the naked blade with white silk’.

‘On the way back I’ll show you where the Japanese landed,’ Sele said. ‘Local people told their spies the wrong place!’

The sudden silence that followed once the truck had stopped wrapped us in a cloak of birdsong, the laughter of children, tiny waves rapidly lapping on the shore and cicadas racketing in the tropical heat. War seemed a distant memory and little appeared to have changed for millennia. Milne Bay is one of the least disturbed areas in the whole country.

East Cape has glaring white coral beaches, a decaying schooner hauled up under the palms and a granite Methodist Mission Memorial baking in the sun. The small village of Bilubilu is nearby. Across the Goschen Strait the looming bulk of Normanby Island seemed to deserve its reputation for sorcery and cannibalism. Sele and the girls unpacked our lunch and I sat with my back against a gnarled tree at the edge of the turquoise sea and ate my sandwich, watched carefully by a group of shy children who put their fingers in their mouths and tugged at their clothes.

The cobalt waters that swirl up between the vastness of the Coral and Solomon Seas are diamond clear and support an unparalleled profusion of marine life. Many forms are still to be classified by biologists. The reef drop-off is perfect for snorkelling. More screams of laughter as I climbed into my diving gear – lycra suit, gloves, booties, fins, mask and snorkel. Coral cuts become infected in seconds in these warm waters, so rich are they in bacteria. There are the added attractions of fire coral that cause long blisters when touched, lionfish with beautiful but treacherous spines, cone shells that shoot poisonous darts, stinging hydroids, the occasional shark. I was taking no chances. Children swim constantly with no protection but I never saw an adult Melanesian swimming for pleasure.

As I slowly headed out to sea, superb tropical fish and a kaleidoscope of soft corals were laid out beneath me like a living carpet. Visibility in these glassy waters can be as much as fifty metres. Tiny electric-blue fish formed constellations around isolated outcrops of rock; rainbow fish swam lethargically away to shelter beneath the coral shelves; butterfly fish abstractly painted in swathes of luminous purple and chrome yellow shot into crevices; black and wild-green specimens with long, pointed mouths ignored me completely; gossamer-thin angel fish flowed in the crystal current like fabric; fantastic lacy scorpion fish mimicked plants and defied my most careful observation. The seabed as far as I could see was covered with ultramarine starfish, mauve-tipped clusters of beige coral and enormous brain corals. I remained among these enchanting coral gardens for more than an hour.

Sele seemed pleased that I had enjoyed my swim until I mentioned the skull cave I knew was nearby. In the Massim the dead were buried twice. In the second interment, bones were placed on rock shelves overlooking the ocean, or in dank underground holes near the shore. The cave was five minutes from the village, but no one would agree to show me the place. There remains a great fear of sorcery and witchcraft in Milne Bay. Strange apparitions still manifest themselves at sea in contradiction to mission teaching.

‘We don’t believe in such things anymore,’ Sele said not terribly convincingly.

‘Well, then, it doesn’t matter if you show me.’

He would not argue and shuffled about looking at the ground, occasionally spitting a jet of crimson, anxious to be off. The girls too had lapsed into silence.

‘The first mission school was called Under the Mango Tree. We were happy.’

As he crunched the Toyota into gear a couple of young boys chewing betel nut and dressed in sharp sports-shirts begged for a lift into Alotau. There is no bus service and hardly any transport this far along the Cape. Sele politely asked me if I minded, so naturally I agreed. They gratefully climbed into the tray behind the cab. As we jolted along I pointed to a pretty bush-material hut on stilts standing in the water and asked the girls what it was. Screams of laughter came from the back seat.

‘A toilet!’ they said after catching their breath.

Soon after leaving we were flagged down by some local Tavara villagers whose banana boat had run out of petrol during their Sunday outing. They also piled into the back. Sele ignored our precariously perched passengers despite the lurching of the vehicle, which threatened at any moment to catapult the whole laughing crew into the palms. Clearly they were accustomed to hanging on for grim death. We stopped at a small beach overhung with rosewood trees, a few rusty spikes poking up through the tide washing the sand.

‘This is Wahahuba where the Japanese landed. Wrong place! They came on a raining night and crawled under the huts. We thought they are dogs and pigs looking for dinner.’ Sele smiled with strange equanimity.

‘Were the people frightened?’ One inevitably asks trite questions concerning war.

‘Much shouting out. One meri1 quickly grabbed up her covers thinking her baby is there, rushed away, but later she finds her bundle is empty. Terrible.’ Sele seemed almost tearful. ‘They bayonet people to keep them silent.’

On the showery night of 25 August 1942, a heavy naval bombardment preceded the attack of the Japanese Special Naval Landing Force. The Japanese began the engagement with only a vague idea of Allied strength. Neither side had been trained for living and fighting in the tropical jungle. Their equipment was inappropriate to combat the incessant rain and mud which destroyed their boots and rotted their feet. Some Australian troops who fought as part of Milne Force were young volunteers of the Militia, popularly known as chocos (chocolate soldiers) or koalas (not to be sent overseas or shot). They had trained sporadically at home during their free time. A great deal of ill-feeling, known as the ‘choco smear’, was expressed towards the Militia by the professional, battle-hardened troops of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) who had recently fought bravely in Tobruk in the Middle East. ‘Scum, scum, the Militia may kiss my bum,’ they would chant derisively.2

The Milne Bay Battle was problematical and confused. Troops had suffered from seasickness on the stinking hulks that brought them to New Guinea. The only food was Bully Beef and ‘Jungle Juice’ distilled from palms. Coconuts fall when the stem swells with moisture, and after rain these missiles killed and injured many men. The troops glowed a livid shade of green from skin treatments and dye bleeding from their wet tropical uniforms. There were no proper maps, only rough sketches of the terrain and their radios were useless. No mosquito nets had been provided. A malignant strain of tertian malaria laid low more than half the fighting force through ignorance of correct preventative measures. Equipment was inadequate. No one knew what was going on.

By dawn of 27 August the Japanese were pinned down by intense strafing by Kittyhawk fighter aircraft of the RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force), some flown by former Spitfire pilots. These ‘flying shithouses’ (as they were affectionately known) were polished with beeswax for speed, but the rain and ooze made flying conditions an indescribable nightmare. Fighters slid off the runway and collided with the bombers. One of the Japanese officers, Lieutenant Moji, became physically ill at the protracted onslaught and in his diary noted in his oddly mechanistic way that ‘the tone of our systems was feverish and abnormal’. However, moments of humour were ever present. Some Japanese soldiers attempted to confuse the Australians by shouting unlikely phrases in English.

‘Is that you, Mum?’ was rapidly answered by a burst of machine-gun fire.

Another four-wheel-drive had become stuck in the riverbed just in front of us. Sele contemplated the scene of impotent activity for a long time. He suddenly gunned across the torrent, all the while being egged on with shouts of excitement and delight from our precariously-positioned passengers. More picturesque tropical beaches were glimpsed through the palms until we encountered the final memorial which marked the western- and southernmost point of the Japanese advance. Some eighty-three unknown Japanese Marines, who made a suicidal charge against impossible odds, lie buried here. The Japanese military maxim, ‘Duty is weightier than a mountain while death is lighter than a feather’, seemed to possess an even deeper significance in this theatre of war. Soldiers would feign death, lying open-mouthed among the fallen, and then the ‘corpse’ would suddenly spring to life and shoot an Australian or American in the back. Numbers of dead are uncertain owing to the large quantity of body parts – legs, arms, hands and heads – that were left hanging sickeningly in the trees after the explosion of bombs and shells.

We arrived back at the lodge as dusk was falling. A late afternoon storm was gathering in the mountains. ‘General’ Mocquery was seated on the veranda in his customary position near the fans talking to a tall, fair-haired man whose complexion and features betrayed all the signs of having spent many years in a tropical climate. He was wearing shorts and his bare legs carried a number of small plasters covering insect bites. Slightly damp, thinning hair accentuated his faintly feverish appearance. Mocquery in full tropical fatigues gestured for me to come over.

‘… no dental treatment available at all,’ he concluded and glanced up.

‘Good trip to East Cape?’

‘Marvellous! Went swimming. The water’s so clear!’ I felt elated.

‘I’m Chris Abel.’ The fair-haired man smiled briefly.

‘Ah! I’ve been waiting to meet you.’

‘You must be the writer fellow.’ His voice betrayed unusual caution. An engaging yet slightly defensive attitude revealed itself in his English accent. We shook hands and I flowed into a bamboo chair.

We discussed his childhood on Kwato Island and his grandfather, Charles Abel, the famous and controversial missionary.

Chris had spent some twelve years in Popondetta as an Agricultural Extension and Development Bank Officer. During an election it was discovered that many of the villagers were unable to read the ballot papers, so he invented what they called ‘the whisper vote’. The locals would whisper their choice in his ear, and he would mark their ballot paper accordingly.

Large drops of rain began thudding onto the roof with increasing velocity. A mysterious figure carrying an ancient Gladstone bag wandered onto the veranda. He was wearing a beige linen suit, maroon-spotted cravat and heavy brogues. His engaging face and sculpted beard achieved a wan smile, but he was way overdressed for the tropics and sweating heavily.

‘A Victorian detective looking for the ghost of a missionary,’ Chris Abel commented wryly.

The BBC were making a programme about the Reverend James Chalmers, a famous nineteenth-century missionary eaten by cannibals on Goaribari Island in the Gulf of Papua. The next day I saw the optimistic film crew board a decrepit yellow coaster and dissolve offshore in a dark tropical storm. Abel suddenly turned to me.

‘And what exactly are you doing here?’ His eyes hardened and a measure of suspicion crept into his voice.

‘Just travelling around the islands and writing about the culture,’ I answered carefully.

‘A couple came here recently for a good reason.’ He emphasised the words meaningfully. ‘A lad came back with his father who had fought in the Battle of Milne Bay. He’s going to write a book about it.’

An atmosphere of unspoken confrontation entered the conversation. He seemed suspicious of writers. Russell Abel, his father, had written an excellent biography of Charles Abel in 1934 called Forty Years in Dark Papua. But the latest published biography of the missionary had made the whole family angry. One reviewer reported that the book contained errors, twisted facts and nasty allusions.

‘And we gave the writer access to all the private papers.’

Clearly I had uncovered a nest of scorpions. The downpour blotted out the light and almost stopped conversation. He was forced to shout over the noise. Water was swirling everywhere and the storm drains were overflowing. He raised his hands in a gesture of hopelessness at attempting to talk over the hammering rain. The fans rushed moist air over our faces.

‘I’ll dig out some books for you to look at. You can set the record straight!’

‘I’m going to Samarai and Kwato tomorrow in the Orsiri1 dinghy.’

‘Have a good trip!’ he shouted as his slender figure disappeared into the murk.

‘What was all that about?’ commented Mocquery rhetorically.

‘I have absolutely no idea.’

1Pidgin for ‘betel nut’.

1‘Masurina’ means ‘the fruits of an abundant harvest’ in the local Suau language.

1‘We work at the Lodge in the kitchen.’

1Originally a Milne Bay word long used for white men, probably meaning ‘stranger from across the sea’.

1Pidgin for Papua New Guinean woman.

2At the outbreak of the Second World War, Australia maintained three separate armies of volunteer personnel. The Militia were part-time, citizen-force volunteers ineligible for service outside Australia or its colonies. The Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) was a highly-trained volunteer force eligible for service anywhere overseas. Finally, there was the permanent army made up of a relatively small force of trained volunteers. There was friction between these armies due to the differentiation of combat role and degree of professional training. Many Militia units subsequently distinguished themselves abroad when their theatre of operations was extended.

1A local trading company based on Samarai Island in China Strait.