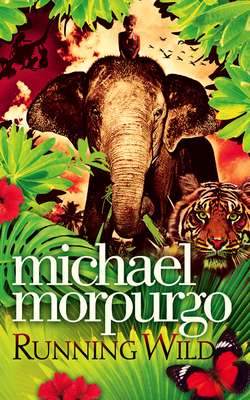

Читать книгу Running Wild - Michael Morpurgo, Michael Morpurgo - Страница 8

“No leaves, Oona, I can’t eat leaves”

Оглавлениеwas being rocked so violently from side to side up in my howdah that it was all I could do to avoid being thrown out. I learned fast that I had to keep my head down, that whenever I looked up, there’d be some overhanging branch just ahead of me, waiting to slash and whip and claw at me, or even to knock me off altogether. So I flattened myself face down into the cushion, closed my eyes, and with all my strength, just hung on, riding the pitch and toss as the elephant blundered through the trees, trumpeting in her terror.

It was the trumpeting I could not stand. It was so loud, so excruciatingly shrill, that it filled my whole head, and the whole forest around me too. I longed to put my hands over my ears, but I could not let go of the rail. The elephant’s terror became my terror, and I found myself screaming into the cushion, then biting deep into it, because it was the only way to silence my screams. I’d been to the funfair with Dad, done the Big Dipper and the Waltzer, but that had all been make-believe terror, terror I could laugh at, terror I had to laugh at because Dad was, because everyone was, even though I was frightened out of my wits. But this, this was the real thing, this was life or death – I knew it because Oona was trumpeting it. I had no idea then what she was running from, only that whatever it was must be close behind us and coming after us, and would kill us if it caught up with us.

It wasn’t until I felt the sun hot on the back of my neck that I realised we must be out of the dark of the forest. I dared now to lift my head at last and look about me. Oona was charging on through a clearing with high grass and scrubby trees all around, and then into a swamp. It occurred to me at once that if I threw myself off here, then at least I would have a soft landing. But then, the more I thought about it, the more I knew I could never bring myself to do it. It was so far to fall, too far, and Oona was running on now even faster than before. I was still being tossed about in the howdah. I was having to hang on with all my strength so as not to be thrown out. But at least I had discovered a technique for staying in there by this time. Splaying my legs wide behind me, I found I could brace my feet against the rails, and steady myself better. I was beginning to feel a little more secure. I even dared to raise myself up a little, and twist round just for a moment to look behind me to see if the mahout had been following us. I’d been hoping against hope all along that he wouldn’t be too far behind, that Oona would slow down, and he would catch up, that somehow, some way, he would be able to bring the runaway elephant to a halt. But Oona was showing no sign of slowing down, and the young man was nowhere to be seen.

All this time I was trying to take it all in, to make some sense of it. Everything had happened so fast, and was still happening. All I could be sure of now was that I had no one to turn to, that I was quite on my own. I was being carried off into the forest by a rampaging elephant, who had been spooked by something or someone unknown. Whatever it was had transformed her from a ponderous creature of supreme gentleness and serenity, into a wild raging beast, maddened by terror, who seemingly had only one idea in her head, to get as far from the sea as possible, as fast as possible.

Ahead of us, beyond a clearing, I saw there was a wide rock-strewn stream. I was sure that Oona must have to slow down to cross it – I hoped she might even stop altogether. She did neither. She ran straight down into it, launching herself into the river, so that the water exploded all around us, soaking me to the skin. Once through it and out the other side I saw that there was a long open hill ahead of us before we could reach the tree line again. Only once she was climbing the hill, did Oona at long last slow to a hurried scuttling walk, her head nodding vigorously with the effort of it, her great ears flapping. I found the ride was suddenly easier, so I got up on my knees now, still holding on, to see better where we were going, where we had come from. I swivelled round so that I could look behind us, back over the canopy of the forest, back the way we had come, down towards the blue of the ocean beyond.

Only now did I understand what it was that had spooked the elephant, and why she had kept running all this time. Everything I was seeing filled me with horror. A warm shiver of fear crept up my spine and into the back of my neck. The sea was rearing itself up into a towering wall of green water that was rushing in towards the beach, towards the hotel, towards where I knew Mum was swimming. I could hear it now too, a distant thunderous roaring. People were running for their lives up the beach. I couldn’t hear their screams, they were all too far away. But in my head I heard their terror. I saw boats being picked up like toys, only to disappear moments later, simply swallowed by the sea.

The great wave didn’t curl over and crash along the beach as I was expecting, but just kept coming, on and on, so fast and so high that it was unreal. It seemed to me like a virtual wave, an impossible wave. There was no beach to be seen any more now, and as I watched I saw that the hotel itself was surrounded entirely by seawater, the first floor already overwhelmed. Everywhere, the water was full of swirling debris: cars, trees, telegraph poles. Entire roofs of houses were being swept along in the torrent like paper hats. I could see there were people caught up in it too, clinging on wherever they could. Any moment now I expected to see the wave crashing through the forest below us, and come rushing up the hill after us. All I knew was that I had to get away, I had to go higher. It was my only chance.

I leaned forward and slapped Oona on the neck, again and again, screaming at her to get going, to go faster. Whether or not she understood I did not know, but to my great relief, I felt her gathering her strength underneath me and then breaking into a lumbering shuffle up the hill and into the forest. All the while I was trying to come to terms with what I’d seen. I was sure by now that it had to be a tidal wave, a tsunami. I’d seen one in a natural history programme I’d watched back home, a virtual one that had been set off after the volcanic eruption on Krakatoa. But this one was for real, and this was now. I had witnessed the terrible power of it with my own eyes.

Knowing it and understanding it for what it was had a strange effect on me. I found myself suddenly calmer, more able to think things through. I now realised that Oona must have sensed the danger, must have felt it coming long before she saw it, and long before anyone else saw it too. I recalled then something the mahout had told me, how she’d been so nervous of swimming in the sea earlier that morning. Somehow, even then, hours before, she had felt that something was out there, was on its way. That must have been why she’d turned and run when she had, and that was the only reason we had got this far, the only reason I was still alive, that we were both still alive.

I could tell Oona was tiring now after all her efforts. Her breathing was laboured, her steps faltering. I should have been ready for it, but I wasn’t. When Oona stumbled and nearly fell, I was hurled to one side of the howdah, losing my grip almost entirely. I just managed to cling on to the rail with one hand as I was flung over the side. I found myself dangling there, barely able to hang on, as Oona barged and blundered her way through the undergrowth. All I knew was that if I let go, even if I survived the fall with no broken arms or legs, I would not stand a chance on my own without the elephant. I had to hang on. Somehow I swung myself round so that I could cling on with both hands, trying all I could to scrabble up the elephant’s side, and haul myself up. But I hadn’t the strength to do it. I knew that sooner rather than later, my grip must weaken and I would fall, or that maybe a branch would knock me off as Oona charged on.

I cried out to Oona then, begging her to slow down. Incredibly, she did. Even more miraculously, she came to a stop. Then I saw her trunk come curling round, felt it grasping me by the waist, lifting me up and depositing me in an ungainly heap back in the safety of the howdah, where I lay for some moments limp and breathless. Already Oona was on the move again, walking on slowly at first, as if allowing me time to recover. I rolled over on to my front, and reached out for the handrail, bracing myself again with my feet, as Oona gathered speed. I closed my eyes, gritted my teeth, and determined there and then that nothing would ever make me let go again.

Only now, as I lay there exhausted in the howdah did I really begin to take in the dreadful meaning of everything I had just witnessed. If Mum had been in the sea, or on the beach, or anywhere nearby when the tidal wave swept in, then she must have drowned, along with anyone else in its path. No one caught on the beach or in the sea could possibly have survived the onslaught of such a gigantic wave. No one would have stood a chance. She had told me she was going for a swim. It was almost the last thing she’d said to me. I tried not to believe what this meant, but I had to. Choking back my tears, I kept telling myself that there was at least a possibility that Mum might already have left the beach by the time the tsunami struck, that maybe she’d been back in the hotel, and had reached the safety of our room, which was after all on the top floor. If so, she could still be alive. She could be. I so wanted to believe that.

But I only had to think again, and I would know in my heart of hearts, that in all probability she had to have been in the water when the wave struck. I knew how much she loved her swimming, and her snorkelling, how for a whole week now she’d hardly ever been out of the water, how each morning we’d raced each other down the beach and into the water, and how she always swam like a seal, effortless and powerful.

That last thought gave me a sudden lift of hope, that maybe even if she had been caught by the wave she might, just possibly, because she was such a strong swimmer, have been able to swim her way to safety. But I realised that Mum’s best chance of survival had to have been the hotel. I tried all I could to persuade myself that she might have gone back to the hotel, to email Grandpa and Grandma again maybe, that she had been up there in our room when the wave came in, that she was alive, that she was not dead and drowned, that she was right now thinking about me, that she’d be looking for me, coming to find me, as soon as she could.

I tried all I could to convince myself that this must be true, and that the worst had not happened. But the more I thought about it, the more I was afraid that it had. As a last resort, I began to pray for God to look after her, to save her, until I remembered that the last time I’d prayed like this, it had been for Dad the night before he went away to the war. God hadn’t been listening then, so why should he be listening now? In my despair, I lifted my head and cried out loud, not to God, but to Mum. “Don’t die, Mum. Please, Mum. Swim, you’ve got to keep swimming, you’ve got to. Don’t give up, please don’t …”

I was interrupted by the sound of a strange throbbing, distant at first, but suddenly quite close and then right overhead. I could see what it was now – a helicopter, glinting in the sunlight up above the canopy of the trees. I was up on my feet at once, balancing as best I could in the howdah, waving my arms wildly and shouting at the top of my voice. But the helicopter was gone within seconds. Just that glimpse though was enough to give me hope again. I knew for sure that they must be looking for survivors, rescuing people, and that one of them could be my mother.

It was at that moment that I made up my mind. Whatever had happened I had to go back to try to find Mum. I yelled at Oona to stop. She didn’t pay any attention. I pleaded with her, I shouted at her, I screamed at her, I slapped her neck. Then, when I could see that none of that was doing any good, I tried explaining. “She could be alive!” I told her. “I have to go back. I have to. Turn round, Oona. You must turn round. We have to go back!” But Oona would not be stopped. If anything, she was going faster, blowing and puffing as she went, striding out more purposefully than ever, her trunk swinging, her great ears in full sail. She was going where she was going, and that was that.

I realised then that there was nothing whatsoever I could do to change her mind, and that I had to go where the elephant was going. I had no choice. Understanding this first, then simply accepting it, seemed to enable me to calm down enough to think straight. Hadn’t this elephant already saved my life? Hadn’t she known exactly what she was doing right from the start? If so, then she was refusing to stop because she knew that the only safety for us both lay ahead of us high in the hills, deeper into the jungle, and that the quicker we got there the better.

I was also beginning to think that maybe this elephant understood things a lot better than I could ever have imagined, that she would not listen, would not turn round and go back, because there was just no point. She knew, as I did, if I was really being honest with myself, that no one could possibly be alive back down there on the coast, and that there was no use any more in pretending otherwise.

As Oona made her way ever onwards and upwards into the forest, I lay there in the howdah, on my back now, staring blankly up at the trees above me, consumed utterly by despair, numb with grief and longing. I had no tears left to cry. I could feel the elephant was exhausted, that her stamina was fading fast. She was stumbling more often, breathing harder. She plodded on, tugging at the leaves around her from time to time, feeding as she went. By now though, I no longer cared what she was doing, or where she was going, or even what might happen to me. I did not care about the oppressive humidity of the jungle, nor the flies that settled on me and bit me. I was not frightened in any way by the wild wide eyes of monkeys blinking down at me as I passed by underneath.

After a while I think I became altogether unaware of the passing of time. Night and day were the same for me. I was neither hungry nor thirsty. I drifted often into sleep, but even when I was awake, I was barely more conscious of what was going on around me than when I was in my dreams. I was aware of the moon floating through the treetops, of the buzz and drone of the forest in the heavy heat of the day, of the raucous cacophony of screeching and howling that filled the jungle every night, of the sudden torrential downpours that somehow found their way through the canopy of trees and drenched me to the skin.

None of it bothered me, none of it meant anything to me. I suppose I wasn’t even aware enough of my surroundings to feel alarmed or threatened. It did cross my mind sometimes that I was in a place where there must be all manner of poisonous snakes and scorpions, and maybe even tigers too – I remembered, in that holiday brochure, seeing a photograph of a tiger prowling through the jungle. I could not have cared less. I was too lost in misery and grief to be fearful of anything.

[bad img format]

I lay like this in my howdah for days and nights on end. I must have drunk from time to time from the bottle of water Mum had given me. I don’t really remember doing it, but I must have done, because I woke up once to discover that the bottle was empty. I kept slipping in and out of my dreams, not wanting to wake at all, because I knew that when I did, I’d remember all over again everything that had happened to me and all that it meant: that I had no father, and now no mother, and that I myself would very probably die out here in this jungle. I was so tired and weak and dispirited by this time, that I didn’t much mind if I did.

My only comfort was the regular rocking motion of the elephant beneath me. I became so attuned to it, that I always woke whenever it stopped. Often I would hear Oona tugging at the branches then, grunting contentedly as she grazed the forest. And from time to time, whenever she flapped her ears, I’d feel a cooling breeze wafting over me. I came to love those moments. And when I heard the sound of her dung falling, I became accustomed to waiting for the smell of it to reach me. It wasn’t unpleasant, no worse anyway than the smells human beings make. In fact, I didn’t find it unpleasant at all, it was strangely reassuring. And it made me smile.

I woke up one morning to feel the soft tip of Oona’s trunk touching me. She was breathing me in, exploring every part of me, from my feet to my face. When she tickled my neck, I couldn’t help laughing a little. And then, without thinking about it, I reached out and touched her trunk. As I did so, Oona left it where it was, deliberately it seemed to me, and let me run my fingers along it as she breathed gently on my face. It was like the breath of new life. I knew then that I wasn’t alone in the world, that I had a friend, and that I wanted to survive, that I somehow had to survive, so I could go back to the coast, and find Mum.

But with this new-found will to live came a sudden unbearable hunger, and with it an overwhelming thirst, a craving for water so strong and all-consuming that I could think of nothing else. I did sometimes manage to grab an overhanging leaf and lick the rainwater from it. Whenever it rained, I’d cup my hands and catch all I could. But there was never enough for me even to begin to quench my thirst, let alone fill my bottle, which was what I knew I had to do if I wanted to survive.

I tried to make Oona understand this every time we came to a stream – and there were enough of those in the jungle – but every time Oona just waded on through and would not stop. I tried whispering gently to her, as I’d seen the mahout doing back down on the beach, but it proved to be no use at all. Shouting at her and slapping her neck did not work. Neither did begging or pleading. Stream after stream we crossed, and all I could do each time was gaze longingly down at the rushing water below me that I so longed to be drinking, but was already leaving behind me.

Again and again I seriously considered standing up in the howdah, and then throwing myself off into the water when we came to the next stream. I would pick my moment, decide where the water was at its deepest, and leap. I could do it. I could swim well enough – the best in my class at school, better than Charlie or Bart or Tonk. That wasn’t my worry. I had other anxieties. If I got it wrong, I could land badly on hidden rocks beneath the surface. I could break a leg, or even my neck. And I knew that rocks weren’t the only danger lurking beneath the surface. I was sure there were crocodiles in these rivers. I was sure because I’d caught a glimpse of one, half submerged. It had looked like a log, but if so, it was a log with a tail, and a tail that moved too.

And anyway, even if there were no crocodiles down there waiting for me, even if I had the best of landings, and had the long cold drink I was yearning for, and managed to fill up my water bottle, would Oona stand there and wait for me while I drank? Even if she did, how was I going to climb back up on to her again afterwards into the safety of the howdah? Getting on and off this elephant was something I just didn’t know how to do on my own. The last time I’d had to do it, days before now, the mahout had been there to help me up, but I could not remember for the life of me how he’d got me up there. All that seemed to have happened so long ago now, before the wave came. Mum had been there. Had she helped me up? I couldn’t remember. I didn’t want to remember.

My longing for food was becoming every bit as frustrating and urgent as my longing for water. It wasn’t as if there wasn’t fruit in abundance all around me in the jungle, but none of it was fruit I recognised, and anyway I couldn’t get at it. I was looking for bananas – I thought there must be bananas in a jungle – but so far as I could see there were none. There was a small pinky-red fruit, that was shaped something like a banana. But these were always tantalisingly out of reach as I passed by underneath. There were sometimes coconuts, orange, not brown, but anyway they were always growing far too high up. And those that had fallen on the forest floor were of course just as inaccessible to me.

There were plenty of other strange fruits I certainly would have tried, had I been able to get near enough, or quick enough to grab them. But Oona swayed on blithely by, quite oblivious, it seemed, to all my needs. And all this time she was adding insult to injury, because of course Oona could reach out her trunk whenever she felt like it, and with a tug at an overhanging branch, was able to pull it down and eat her fill on the move. Worse still she looked and sounded as if she was enjoying every moment of her feasting. I could only sit there and listen to her great jaws grinding away, to her almost constantly rumbling stomach. Elephant digestion, I was discovering, was noisy, and infuriating, punctuated as it was by rumbling groans of the deepest satisfaction.

In the end it all became too much for me to take. I bent down and bellowed into her ear. I knew it was pointless, but I did it all the same. “Food, Oona! I want food! I want water!” She flapped her ears at me then, as if she was batting away my words like irritant flies. But I kept on at her, whacking her as hard as I could on her neck, on her back, anywhere I could hit her, trying everything and anything to make her listen. “I want to eat, Oona!” I cried. “Fruit. I need fruit. And water, I’ve got to have water. Please, Oona, please. Can’t you understand, Oona? I’ll die if I don’t have a drink. I’ll die!”

In time I discovered that all the bellowing and the whacking and the slapping was hurting me a great deal more than it was hurting her. My hands ached with it. My throat was raw with it. Whatever I said or did, the elephant was not paying me any attention, that was for sure. She simply continued on her wandering way through the jungle, munching nonchalantly as she went, seemingly without a care in the world. I tried everything I knew over and over again. But even as I was doing it, I could see it was useless, that neither sweet-talking, cajoling, begging, whacking, or threatening was ever going to work. This elephant would do what she would do, and that was that. In the end I simply gave up trying.

Exhausted and angry, I lay down in the howdah, which I now thought of more as a cage than a throne, and sobbed. Into my head from nowhere came Dad’s old joke: “You’ve got to chill, Will.” I said it out loud then, as Dad would have said it. “You’ve got to chill, Will.” Repeating his words time and again was a comfort to me somehow. It was the rhythm of them maybe, or the familiarity. I longed for sleep, because I longed to put out of my mind everything that had happened, all the discomforts I was enduring. It was the only way to forget the gnawing hunger in my stomach, that my tongue was leathery dry, that my throat was parched and sore.

Once, when sleep came at last, I heard Dad’s words again in my dreams, and I saw him too. “You’ve got to chill, Will,” he was saying. “You’ve got to keep it going. You can do it, Will.” I was back in the sea at Weston when I was little. I was swimming towards Dad, who was holding his arms out towards me. I was kicking my legs frantically, trying all I could to keep my chin above water, trying to reach those outstretched hands before I sank, but the seawater kept coming into my mouth and was choking me. I woke then, suddenly, and sat up spluttering. For a few moments the sunlight blinded me.

The elephant had stopped. There was the sound of rushing water all around me. I sat up. Oona was standing in a river, the water washing over her back and up to her neck and her ears, so that the howdah was simply an island now, the river swirling all around. And somehow the howdah had worked itself loose. I could feel it shifting sideways off Oona’s back, so that some of the cushions were already waterlogged. The river was running fast, but I did not hesitate. This was the chance I’d been waiting for. The shore wasn’t that far away. I could make it. If there were crocodiles I did not care. I needed to have water. I had to drink.

I put a foot on the rail and leaped off. Before I knew it I was in the river, and swimming hard for the shore. Just a few strong strokes and I was there. I crouched at the river’s edge and drank till I could drink no more, filling myself to bursting. Breathless with drinking now, triumphant with it, I found myself laughing and whooping and slapping the water, filling the forest with my noise, sending thousands of screeching birds flying up out of the trees. “Look at them, Oona!” I cried. “Look!”

All I could see of Oona was her head and her trunk. She seemed to have drifted further down the river, and was right out in the middle now, where the flow was faster. I was quite confident I could swim that far. So without another thought I plunged in. But I found that the current was a great deal stronger out there than I had imagined, and I soon realised that I wasn’t going to make it. I just didn’t have the strength to sustain the effort. So I had to turn back again, and swim hard for the shore to get myself out of trouble. It was a long swim and I felt myself tiring fast, so it was a huge relief when I felt my feet touch the bottom, and I could clamber out of the river at last.

I looked round then to see where Oona was. She had vanished. Panic-stricken at finding myself suddenly alone, I began calling out for her, tentatively at first, then louder and louder as my fears multiplied. My first thought was that Oona must have gone off into the forest and abandoned me. I was sure of it. There could be no other explanation. With panic came hurt. I let her know just what I thought of her. “Go off and leave me then, you great lump, see if I care! I don’t need you, you hear me? I don’t need you!”

It was then that I caught sight of the howdah being swept away downriver towards the rocks, but there was still no sign of Oona. The howdah sank as I watched. All I could see of it now were its straps, and then my water bottle and a cushion from the howdah bobbing away into the distance. As I stood there I was thinking that the bottle was the last thing Mum had given to me, that and my hat and the sun cream, all of which must have been at the bottom of the river by now with the howdah. All I had left was what I stood up in: my shirt and my shorts.

That was when Oona erupted from under the water only a few metres from me, rising up to her full height with the water cascading from her, trunk flailing and splashing. When I got over my surprise, I found myself overwhelmed with sudden joy and relief, all my earlier fury at her instantly forgotten. Oona sank down again into the river, leaving only the great dome of her head and her eyes visible. It seemed to me that she had been playing hide-and-seek with me, that this must be an invitation to come and play with her. It was an invitation I could not resist. As I ran down into the water I wondered how I could ever have doubted her.

Oona was better than any wave machine I had ever known. Whenever she rolled over to loll on her side, she created huge waves that I would dive into. Time and again she’d submerge herself completely, then rear up out of the water, so that it came rushing down her sides like a waterfall, and I would stand there beside her, shrieking under the shower she was giving me. She swished her trunk at me, sprayed water at me. It was a performance, a game. I was in fits of laughter the whole time, and loving every moment of it.

I remembered then the last time I had loved messing around in the water like this. It had been with Dad at Weston. I remembered diving down and swimming between his legs, and when I came up again there’d been a long galloping piggyback ride, out of the sea and up the beach towards where Mum was waiting for us. She’d screamed at us not to drip on her, and we had, as she knew we would, shaking ourselves like dogs all over her. It had all been so good. The whole day by the seaside at Weston came back to me, every detail of it, then all the treasured memories of home, of Dad and Mum, of all of us together, of how everything had been before Dad had gone off to the war, before the tidal wave.

I felt suddenly racked by sadness and guilt. I left Oona in the river and went to sit on the rocks. All I could think of was that nothing would ever be the same. Those days were gone for ever. Mum and Dad were gone for ever. I would never see them, or hear their voices ever again. And what had I just been doing? A moment or two before I’d been having the time of my life, shrieking with laughter as if none of this had ever happened, as if everything was just ‘fine and dandy’, as Grandpa used to say. Dad was dead, and down on the coast hundreds of people had been drowned by the tidal wave, thousands maybe, Mum among them. How could I have allowed myself to forget them both so quickly? How could I have been laughing when I should have been crying?

But even as I was thinking this, even as I watched Oona wafting her trunk at me from way out in the river, I found I was smiling inside myself, and I knew there was nothing wrong in it, that Mum and Dad wouldn’t mind. There was a hummingbird hovering nearby over a flower. She was so tiny, miraculously tiny, and beautiful. And butterflies of all colours were chasing each other over the water. That was the moment I felt all the gloom and guilt lifting from me. I was not thinking of the past any more, nor of Mum and Dad. I was thinking that if I had any family at all now, it was Oona. It was a strange idea, I knew that. But the more I began to think about it, the more I believed it was true.

As I sat there watching Oona in the river, I began to take stock of my whole situation. I knew for certain that without Oona I would not have survived at all, I would have no hope at all, I’d be utterly lost. I had only seen that one helicopter, and that was a few days ago at least by now. The only evidence I’d seen of any human existence was the occasional glimpse of a vapour trail high in the sky, thousands of metres above the canopy. No one knew I was here. No one even knew I was alive, so certainly no one would be out looking for me. I had ridden into this jungle on the elephant. If anyone knew the way out, I reckoned, it was her. All I had to do then was to stay with her, and learn to live with her, and I’d be all right. One day sooner or later she’d carry me out of the jungle, just as she’d carried me in.

Meanwhile I had to find some way of communicating with her, of getting her to understand I was starving hungry. I’d heard the mahout talking to her down on the beach that morning, but it had been in his language, a language I hadn’t understood at all. Oona must have understood, though, otherwise why would he have talked to her as much as he had? So if she had understood his language then she could learn English – it stood to reason. All I had to do was teach her. I remembered how her mahout always whispered to her, never raised his voice. I would do the same. Somehow I had to teach her to understand me.

I wasted no time. As soon as Oona came out of the water, I went right up to her. I held her trunk and stroked it as I talked to her, just as the mahout had done. As I spoke I was looking her right in the eye, her wise, weepy eye. “Oona,” I began, “I know your name, but you don’t know mine, do you? You don’t know anything about me. So I’d better tell you, hadn’t I? Here goes then. I’m Will. I’m nine years old, ten soon, and I live near Salisbury in England, which is a long way away, and that’s where I go to school. My Grandpa and Grandma have a farm in Devon, where it’s muddy, and he’s got a lot of cows, and a tractor, and I go there for holidays. Dad was a soldier and he was killed by a bomb in Iraq because there’s a war there, and now I think Mum’s dead too, drowned by that big wave, the one you saved me from. If you hadn’t done that I’d be dead by now, like she is. But the thing you’ve got to understand is that I’ll be dead anyway pretty soon, if I don’t get some food to eat. I’m hungry, Oona, really hungry. I need to eat. Understand? Eat.”

I opened my mouth wide, said “aah” several times, sticking my fingers down my throat. Oona looked down at me knowingly from a great height, so knowing that I felt she must be understanding at least the gist of what I was saying. Much encouraged by this I went on. I rubbed my stomach. “Yum, yum. Food. Food.” Unblinking, she looked back at me. She was listening, I could tell that much, but now I wasn’t so sure she’d understood a single word I’d been saying.

Maybe her eye wasn’t knowing after all, simply kind. I just didn’t seem to be getting through to her. I had an idea. I decided I’d have to try another tack altogether. I ran off to the edge of the forest, and came back after a while with a long leafy branch I’d torn from a tree. I offered it to her, hoping these might be the kind of leaves she liked. She sniffed at it for a few moments, then curled her trunk around it, ripped off what she wanted and shoved it into her mouth. “Yes, yes, Oona,” I cried. “You see? Food. Yum, yum. Me. Me too, I need food. But not leaves, Oona. I can’t eat leaves. Fruit. Fruit.”

As she chomped and chewed her eyes never left me once, and from somewhere inside her there came a deep groan of contentment. I was hopeful that these were all signs that she understood now, that she was grateful to me for fetching her food, that she would do the same for me. But when she’d finished stuffing in the last of her leaves, all she seemed interested in was exploring my hair and then my ears with her trunk. Exasperated now, I lost my patience. I pushed her away, and shouted up at her. “Can’t you understand anything, you stupid elephant? I’m hungry! I just want food! I have to have food!”

I looked around in desperation, and saw there was some kind of red fruit, they looked like huge ripe plums, and they were growing high up in a tree on the far side of the river. “There! Look, Oona! That’s what I want. It’s too high for me to climb. You could reach them easy as anything, I know you could. Please, Oona, please.” But Oona just turned from me and began walking away from the river and up into the trees, her trunk searching out more leaves. Once she was busy eating again, I discovered that no amount of yelling at her, or leaping up and down, or slapping her leg would distract her. Oona was feeding, and nothing and no one was going to stop her.

I felt my eyes filling with tears. I tried to blink them back. But it was no good – they kept coming anyway. I sat down beside the river, clasped my knees to my chest and let the tears flow. I was sobbing not out of self-pity or grief. There were no thoughts any more of Mum or Dad. I was crying out of fury and frustration, and hunger too. I buried my face in my hands and rocked back and forth, moaning in my misery.

When at last I did look up again, I saw that the howdah had now become firmly wedged between rocks. It was obvious that there was no possible way I could retrieve it from the river. Without it, I knew I could never ride Oona again. And without Oona how was I ever going to be able to find my way out of this forest, and back to safety? Strangely, it was only now, as I came to understand all this, that I finally stopped crying, and began to calm down and collect my thoughts. If I couldn’t ride the elephant, and if she wouldn’t find me food, then she couldn’t save me. In which case I’d have to search for food myself, fend for myself. I’d have to find another way altogether of saving myself. There had to be a way out of the jungle. There was a way into this place, so there was a way out. I’d just have to find it, that’s all.