Читать книгу Mr Skip - Michael Morpurgo, Michael Morpurgo - Страница 5

Оглавление

I was forever finding things in that rusty old yellow skip. It was on the corner of the estate by the phone box. Whenever they wanted to get rid of stuff, people from all around used to come and dump things in our skip. I’d go have a look and a good mooch around in there whenever I felt like it.

At first Mum told me I shouldn’t do it because there might be something in the skip that could cut me or prick me or whatever. So I promised her I’d be careful, and after that she was always fine about it. What made her really happy though was when I brought things home. We didn’t have much in our flat – we couldn’t afford to buy much at all – so quite a lot of what we did have came out of that rusty old skip.

I found the blue china horse for the mantelpiece, and Mum was thrilled to bits with it, even though it had a chipped nose and only three and a half legs. Her favourite armchair came off the skip too, as well as the electric radiator. All we had to get was a plug for that and it worked perfectly. But best of all was the twenty-six inch Sony Trinitron television set that I brought home in a wheelbarrow – my cousin Barry gave me a hand. It worked fine except that one of the knobs was missing and the colour was a bit fuzzy. Mum didn’t mind. She was over the moon about it.

Mum often told me I was “a terrible little jackdaw”. And each time she said it she thought it was really funny, because my name is Jackie Dawson, which sounds a bit like jackdaw – if you see what I’m saying. It’s not exactly hilarious, is it? But Mum thinks it is. Mum loves a laugh, but there’s one thing she takes very seriously indeed. Mum likes to keep up appearances. She doesn’t like other people looking down on us or laughing at us – nor do I come to that – which is why she never liked the idea of the neighbours seeing a child of hers crawling about on the skip after other people’s cast-offs. That was why I only ever went rummaging around the skip at dusk or after dark.

I don’t like to upset Mum, because there’s just the two of us, and as she says, we make a great team – her and me against the world. And our world is the estate. There’s things I like about it – I mean, all my friends live here – but there’s lots I don’t like about it. It’s a grey place, and you can’t see the sky because there’s tower blocks everywhere, and some people are sad all the time and don’t smile. We haven’t got much to do on our estate, except watch TV. So most evenings in summer we have races, horse races, and then there’s the big race on Saturday afternoons. I reckon we’ve got more horses around our place than on any other estate in the whole wide world. They’re tough little horses too. They’ve got to be. They live out all the year round, in all weathers, and they soon eat down all the grass, so they’ve never got much to eat. Some people don’t look after their horses as well as they should either and I don’t like that. I always thought that if I ever got rich, I would build a stable for every horse on the estate.

Most of the boys on the estate have horses, and a few of the girls too; but the girls aren’t allowed to race. It’s a boys only thing. The boys call themselves the Crazy Cossacks, and they don’t allow the girls to join in even if they do have horses. If you haven’t got a horse on this estate, then you’re a no-one. If you’re a girl and you haven’t got a horse, like me, then you’re a no-one twice over. All I’ve got is that three and a half legged blue china one on the mantelpiece. The one thing I’ve always longed for all my life is a real live horse of my own that I could look after, that would go as fast as the wind, faster than any of the Crazy Cossacks’ horses.

For just a few weeks last year I was allowed to ride on Dasher, Barry’s horse. Barry’s a little less horrible than most of the other boys on the estate. He’s certainly a lot less horrible than Marty Morgan, but then there’s no-one as horrible as Marty Morgan. Marty’s the chief of the Crazy Cossacks, and he’s a great big oaf, all loud and lumpy, and everyone’s frightened of him, except me. I’m terrified of him, so I keep well out of his way. Even Barry, who’s as big as he is, won’t stand up to him.

Barry’s alright when he’s alone with me. When his friends aren’t watching he can be really quite nice. I’d been begging him for years to let me have a go on Dasher. All Barry would ever let me do was groom him, or feed him or pick out his hooves – and he wouldn’t let me do that very often. Then last year when he got glandular fever, he let me ride him out – not in the races mind – just to exercise him for when Barry got better – which he did, and a bit too soon for my liking. But meanwhile I rode Dasher every moment I could. I had the best time of my life. All I’d ever ridden before was Barnaby, Gran’s old donkey who’s about as old and slow as Gran is. So to ride Dasher for a while was a real treat, even if I couldn’t join in the races round the estate with the Crazy Cossacks.

Anyway, late one evening last week, I was out watching the races, watching Marty Morgan and Barry and the rest of the other Crazy Cossacks as they thundered past me whooping and yelling like a bunch of idiots. I was feeling all miserable and angry. I so wanted to be out there with them, racing them, beating them. To be honest, I was secretly hoping that Barry would fall off, and break his collarbone or something, so that I could ride Dasher again instead of him. Then I noticed a car backing up to the skip. A man got out, opened up the boot of his car, lifted something out and chucked it into the skip. I remember wondering what it was and thinking I’d find out later. Then I forgot all about it for a while, because suddenly Barry did fall off. Sadly for me he didn’t break anything.

After that I was busy for a while catching Dasher. It was always really dangerous for a horse if he was running loose on the estate. They were safe enough in their crowded little paddock behind the estate where most of them lived, or even when they were hobbled and grazing on the grass around the flats; but if they broke free and ran off, then they could be straight out onto the open road and in amongst the cars. We’d had a lot of horses knocked over like that, and I wasn’t going to let it happen to Dasher.

He was in a bit of a panic, so it took me a while to sweeten him in, catch him and calm him down. Barry thanked me as he mounted up again, and said I could groom Dasher tomorrow if I liked. Big deal, I thought. But I didn’t dare say anything. If I upset Barry too much he wouldn’t even let me do that. One day Barry, I thought, one day I’m going to ride in the races myself and I’ll leave you standing, you and your stupid Crazy Cossacks. I’ll beat the lot of you, you see if I don’t.

As I made my way home later in the gathering dusk I was still angry, still dreaming of having my very own horse, and talking to myself out loud as I often did. “There won’t be another like him,” I was saying. “He’ll be the fastest on the estate, the fastest in all Ireland, the fastest in the world. And I’ll be riding into the winner’s enclosure at the Irish Derby, and I’ll leap out of my stirrups like Frankie Dettori. I’ll be the greatest.”

I was still talking to myself as I came past the skip. That was when I remembered about the car backing up, and that man chucking something in. I thought I might as well have a look. I made sure there was no-one about, then hoisted myself up and into the skip. I couldn’t see all that well, and at first there didn’t seem to be much that was new. In fact it was almost empty.

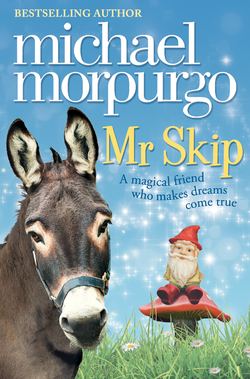

Then I saw him. He was lying there on an old mattress at the bottom of the skip, and he was looking up at me. Well his head was, his face was, but the top part of him was separated from the rest. The other half of him, a very round pot belly and stubby little legs with pointed boots on the end of them, and the toadstool he was sitting on, lay inside a discarded pushchair. In my mind I put the two halves of him together, and recognised him for what he was – a gnome, a battered old garden gnome.

I felt suddenly very sad, very sorry for him, lying there all broken and abandoned and unloved in the bottom of a dirty old skip. I couldn’t leave him there like that. I just couldn’t. And then I had this totally brilliant idea. I’d fix him up, I’d give him to Mum for her birthday in a fortnight’s time. She’d love him, she’d love him to bits.

So, crouching over him and picking up his head I told him my plan. “I’m going to save you,” I said. The moonlight fell on his face, and I could see he was a happy smiling sort of gnome. I thought of his name just like that. “Mister Skip. I’m going to call you Mister Skip, and you’ll be coming home with me. I’ll put you together again. And Mum and me, we’ll look after you, alright?” As I was speaking, his eyes twinkled at me, I was certain of it. It was like he was trying to show me he was happy, as if he was saying thank you. It gave me the shivers to think that this plaster gnome could actually be listening to me, that he could really understand, that he had feelings. But they were nice shivers.

I couldn’t be sure of it, but as I walked away with a half of him under each arm, I honestly thought I heard him chuckling – the top half of him and the bottom half at the same time. It was weird, but I liked it.