Читать книгу Sparrow: The Story of Joan of Arc - Michael Morpurgo, Michael Morpurgo - Страница 6

Оглавление

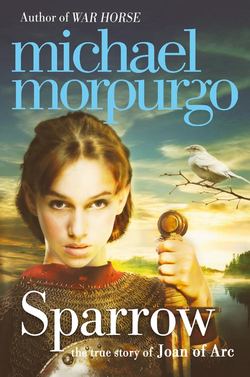

To begin with it was the picture. It was the picture that made it all happen – I am quite sure of it.

In the house where I grew up, in our old house in Montpellier, the picture always hung at the top of the stairs. Every time I went up to bed at night, there she’d be – Joan of Arc in her shining armour, holding her standard, with a shaft of light falling across her uplifted face. I would often gaze up at her and yearn to be serene and strong, just as she was. I wanted to have the same visionary, faraway look in my eyes, and the same hairstyle too.

But I learned very early on that my father did not share my enthusiasm. He disliked the picture intensely, about as intensely as my mother loved it. Apparently it had hung in her house when she was a child. But I didn’t like it just because my mother did. I had my own reasons, reasons I always kept to myself – until now.

My name is Eloise Hardy. I was seventeen last May. Something extraordinary has just happened to me, something so extraordinary that I feel I have to write it down. I want to remember all of it as it really happened, every moment of it, every word of it. Maybe, in the remembering of it, in the writing of it, I will begin to understand it better. I hope so.

One of my very earliest memories is of me standing in front of the full-length mirror in my mother’s bedroom, a red tablecloth over my shoulders for a cloak, a broom with a towel tied to it for my standard. I would contrive to strike my saintliest pose. I once wrote out every adjective I could think of that described her perfectly: noble, honest, kind, brave, and a few others besides. I made a resolution to be all those things for the rest of my life. It lasted for about a day, I think. I read all the books I could find about her; and the more I read, the more I wanted to be her. I made a serious start in this direction when I was about ten years old. Without ever disclosing my reasons I managed to persuade my mother to let me have my hair cut en boule, just like Joan in the picture. Seven years later and it’s still cut the same way. It suited me then. It suits me now.

Thinking back, I suppose I have always been a strange sort of girl, never quite happy being who I was, dumpier, more ordinary than everyone else around me. My face was too round, my hair too thick. At my primary school I was ‘a dreamer’, or so my teachers often said. ‘Bright as a button. Such a pity about her spelling’ ran one school report. Dyslexia was diagnosed. I didn’t mind that much. It made me different, distinctive, for a while at least. Besides, I reasoned, Joan of Arc couldn’t read and she couldn’t write either. And she managed well enough, didn’t she? I found out about all sorts of other worthy people who had done good and great and exciting things in their lives, who had changed the world – Louis Pasteur, Mother Teresa, Mongolfier, Francis of Assisi. But to me these were mere fleeting interests, no more. Joan of Arc, La Pucelle, Johanne of Domrémy, the Maid of Orléans, always remained my real mentor. And as I grew up she became my abiding soulmate.

Just last year, when I was sixteen, I was told we would be moving house. I didn’t want to leave at all. I loved my life in Montpellier, and everything about it. I was happy where I was, with my school, with my friends. But my father, who is a plastic surgeon, had been offered a job elsewhere, a better one, which was far too good an opportunity to turn down, so he said. I protested, of course, but it was no use. The decision had been made. “And anyway,” said my mother, “at least Joan on the staircase will find a good home. It’ll be the perfect place for her.”

“What do you mean?”

“Orléans,” my father said. “We’re moving to Orléans.”

On my way upstairs that night I spoke to Joan, face to face, and silently. “You’ll be going back where you belong, back to Orléans, Joan, where you lifted the siege and drove the English out, where you rode triumphant through the streets, your standard fluttering over your head. We’re going to live there. I’m going to walk where you walked, be where you were. We’ll be together.”

There were no more protests from me after that, and indeed all my anxieties about moving very soon vanished. It wasn’t the end of anything. On the contrary, it was quite definitely the beginning of something. I felt it in my bones even then.

I wheedled my mother into letting me have the Joan of Arc picture to hang in my new bedroom in Orléans. She wasn’t too difficult to persuade – I think she was pleased that I still liked it so much after all these years. My father was, of course, delighted that he wouldn’t have to pass Joan of Arc on the stairs any more. He said as much. “Every time I look at her on my way to bed, she says the same thing: ‘And have you done enough for France today, Monsieur Hardy?’ Gives a man a guilty conscience. As far as I’m concerned you can stick her where you like – just as long as she can’t see me and I can’t see her.”

So now I had my Joan of Arc all to myself in my new room. I hung her above my bed. Neither my mother nor my father really knew how much she meant to me, because I never told them. I never told anyone. I didn’t want her ridiculed – and, I suppose, I didn’t want me to be ridiculed either. I didn’t want her even discussed. They were great ones for discussing everything, my parents. To discuss her would be to share her, and I didn’t want that.

Now that Joan was in my room she became even more my secret familiar, my guardian angel and my talisman. I would reach up and touch her face every night before I went to sleep; and in times of trouble I would even talk to her, but quietly in whispers, so no one could ever hear me. It sounds silly, but I began to hope for, even to expect, perhaps, replies to my questions, solutions to my troubles. None came, of course. I so much wanted to hear voices, as she had. I listened for them, longed for them, but none came.

As time passed, I talked to her more and more often, for my troubles were many. Worst amongst them was the isolation I felt at my new school. I didn’t know anyone, and no one seemed to want to know me – except, that is, for Marie Duval. Whenever she talked to me, Marie Duval made me feel I was the most important person in the world to her. I can’t think why she took me in as she did because she always had friends enough and plenty fluttering around her. There was a kind of serenity about her, a serenity I’d known in only one other person, in Joan, in my picture.

One day our black and white cat, Mimi, fifteen years old and all the brothers and sisters I had, just went off and never came back. Day after day I went miaowing round the streets, tapping her saucer with a spoon. I came home one evening to the news that a black and white cat had been run over at the bottom of our street. I wept all night long, brimful with wretchedness. The next morning I was looking up at Joan, for some crumb of comfort, I suppose, when a sudden bright hope flashed through me. Why had I assumed the worst? There must be hundreds of black and white cats in Orléans. Perhaps Mimi was just lost and couldn’t find her way home. I should go on looking, but further afield perhaps.

So it was that I found myself that same afternoon after school walking along the river towards my favourite place in Orléans, a place I’d often visited before, the river bank opposite the site of the Tourelles, the English fort that Joan of Arc had captured hundreds of years before to raise the siege of Orléans. I sat down at the river’s edge and watched a flotilla of canoes trying to negotiate the fast water under the bridge. A pair of ducks flew in, landed and swam towards me, bobbing comically. I laughed, and felt suddenly overwhelmed by feelings of complete wellbeing, of boundless optimism. Mimi would come back when she was good and ready, she’d gone off exploring. I should just stop worrying.

I looked up across the river at where the Tourelles had once stood, shading my eyes against the sun. The place must have seemed impregnable to Joan, to her soldiers, yet time after time they had stormed the walls. Again and again the English had beaten them back, and every time Joan had rallied her soldiers to the attack. She was first up the ladder, first over the ramparts, her standard whipping about her in the wind. All about her now the cheering soldiers poured over the walls. The defenders were forced back and back, and were finally overwhelmed. The slaughter was bloody and terrible. As her soldiers celebrated, I saw Joan turn away from them. I saw her crying up against the wall, out of joy, out of relief, out of horror.

It was strange. Down here by the river, I could see it all in my mind’s eye so well, so distinctly. She was short, sturdy and dark – dumpy even, just like me. Yet, in my picture at home she was tall and elegant, with the face of an angel – a slim angel. I decided I preferred the Joan of the Tourelles – the Joan of my dreams.

Day after day I came back to the same place – I confess, not to look for Mimi any more, but simply to dream the same dream. I could never lose myself in it for long though. Some earthly distraction or other would bring me back to now – a lorry rumbling over the bridge, the raucous laughter of the canoeists paddling past, or a bird hopping past my feet, usually a sparrow. There was one sparrow in particular, I noticed, that came back and back. He would stand and watch me first with one eye, then the other. So I took to feeding him, to tempt him in even closer. However much I fed him, he always came back for more. And if any of his friends tried to join in the breadcrumb feast, he’d very soon see them off. I could always tell him from the others – he had a white patch on his throat. He was a scruffy looking ragamuffin of a sparrow, but a real character. I called him Jaquot.

Every time I came now, Jaquot would be waiting for me, and I liked that. I really think he looked forward to our meetings as much as I did. He seemed to learn when to leave me alone so I could dream my dreams in peace. When one day I spoke to him it seemed the most natural thing in the world. I told him all about Joan of Arc, about my picture at home, about how she’d stormed the Tourelles and relieved Orléans. I swear he was listening to every word! But when I’d finished he was simply a greedy sparrow once again. In the end I think I went down to the river as much for Jaquot as for Joan of Arc. As for Mimi, I hadn’t forgotten about her. I just knew she’d come back. Somehow I was quite sure of it.

The first I heard of it was on a Monday morning. When I got to school the place was buzzing with excitement. Marie Duval came running up to me. “We’ve been chosen!” she said. It wasn’t entirely obvious to me what we’d been chosen for. So I asked her. Each year, it seemed, one school in Orléans was selected, and from that school one seventeen-year-old girl was chosen to be Joan of Arc, chosen to ride through the streets on a white horse dressed in silver armour and carrying her standard. Whoever was chosen would lead the entire procession. It would be in May, May 8th, on the anniversary of the relief of Orléans, just four weeks away. May 8th? May 8th? May 8th would be my seventeenth birthday!

It was some immediate encouragement to me that half the school, being boys, must be disqualified. But there were at least four hundred girls and about a hundred of those, I calculated, would be seventeen or thereabouts. By that afternoon almost every one of those eligible had put herself forward for selection, a hundred and ten in all, including Marie, including me. A hundred and ten to one. Yet I knew, as I stood there looking at the great long list of hopefuls, that I would be the one to be chosen. I had no doubt about it. We all had to write an essay – ‘The life and death of Joan of Arc’. We had two weeks to finish it and hand it in. The ten best essays would be selected, and for those ten there would be final interviews conducted by the Headmaster and the Mayor of Orléans, and then the winner would be announced.

As I walked home that afternoon I knew for certain that all of this had been meant – the picture of Joan I’d grown up with, the move from Montpellier to Orléans, my new school being chosen for the May 8th celebrations, and the fact that my birthday on the 8th May would make me seventeen and therefore eligible to be the Joan of Arc they were looking for. It wasn’t too good to be true. It was going to be true. It was going to happen. I would write the essay of my life: researching diligently, checking every spelling. I would type it out on my mother’s word processor, so they didn’t have to read my scrawly handwriting. I’d get it done on time, no procrastinations, and submit it. As sure as night follows day, it would be one of the chosen ten. And then, and then…

For two weeks I never once went near the river. Jaquot was abandoned. I confess I scarcely ever thought of him. I delved in the library and read as I’d never read before. Then I settled down and started to type, enlisting the spellcheck on the word processor almost constantly. There would be no mistakes. My mother kept saying I mustn’t get my hopes up too much, that after all I’d only just arrived at the school, that there were a hundred other girls all beavering away at their essays just as I was. But at the same time she was encouraging me to do my best. She’s a writer herself, a journalist, so she knew what she was talking about – in this instance.

“Write it for its own sake, for her sake, Eloise. Try to get under her skin. Try to find the girl behind the legend.” That was good advice. I knew it and I took it, but I didn’t tell her I had. I didn’t tell her either that I knew I was going to win anyway, that it was all fate, all a meant thing. She’d be sure to scoff at that. My father was scoffing quite enough already for both of them. “Lot of old flagwaving drumbeating claptrap, if you ask me. All this dressing-up and parading up and down about something that happened hundreds of years ago. Bit of fun, maybe; but you shouldn’t go taking it so seriously.”

When it came to it, though, he was the first to read my essay. After he’d finished he took off his glasses and looked up at me. There were tears in his eyes. All he said was, “Poor girl. Poor, poor girl. How she must have suffered.” My mother said she never knew that I could write that well. I knew, too, that it was far and away the best essay I’d ever written. I was quite sure, as I handed it in, that it would be one of the chosen ten. I hoped Marie Duval’s would be another. So, when the Headmaster announced the winners, I was pleased when her name was read out, and wildly excited when I heard my own, but not in the least surprised. Everyone else at school was surprised, my teachers in particular; but none of that bothered me. There were a few cruel mutterings about how I must have been helped, but I ignored them as best I could and simply looked forward to the interview and to my inevitable selection as Joan of Arc.

I was nervous before the interview, even though I knew I was going to win. As it turned out, the interview was short and sweet. The Mayor looked just like mayors should look, jovial and well-fed, but worthy with it. He leant forward and asked me from under his twitching eyebrows: “So, Eloise, why do you want to be Joan of Arc then?”

“I’ve always wanted to be Joan of Arc,” I replied. “Ever since I was little.” It was an answer they clearly weren’t expecting, and I was pleased about that.

“Can you ride a horse, Eloise?” the Headmaster asked.

“Yes, but not as well as Joan could,” I said. Just be truthful, I kept telling myself. Joan was truthful, always truthful.

There were a few other questions about how long I’d lived in Orléans and where we had lived before, but none of them was searching enough to worry me. The Mayor’s endlessly twitchy eyebrows made me smile, so that my laughter came easily – I was so relaxed that I was almost sad when it was all over.

There were only two more to go in after me. Once the last interview was over, we didn’t have long to wait. The Mayor and the Headmaster came out together. I could hear my heart pounding in my ears.

“Believe you me, this has been a very difficult choice to make,” began the Headmaster. “There is no question in our minds who wrote the best essay. It was so good, so outstandingly good, that the Mayor has decided for the first time ever, to publish it as an integral part of the May 8th celebrations. However, we both feel we must take other matters into consideration. Accordingly, on account of her remarkable essay, we have chosen Eloise Hardy – as runner-up. But as you know, Eloise has only been living here in Orléans for a few weeks, a very short time. There can only be one Joan a year, I’m afraid. And our choice for Joan of Arc was born in Orléans and has been living here all her life. She, too, wrote a fine essay, and she interviewed well too. So our Joan for this year is Marie Duval.”

Not me! Not me! Marie had her hands to her face, and there was clapping all around me. The Mayor was kissing her on both cheeks to congratulate her, and I found myself doing the same thing like everyone else. Her cheeks were wet with tears, her tears and mine. “I’m sorry,” she said. And I knew she meant it.

“Maybe another year,” said my mother when they came up to my room to console me later that evening. “And, after all, you are having your essay published. That’s much more important.”

“You win some, you lose some,” my father added. He kissed the top of my head and tipped my face upwards so that I had to look him in the eye. “And what do they know anyway?” he said.

They were both kinder, more attentive to me in the days that followed than they had been since I was little. And at school I discovered that Marie Duval was no longer my only friend. Perhaps my essay had earned me some respect; or maybe it was through my losing that I had gained everyone’s sympathy. Either way, I basked in it. So it wasn’t a complete disaster after all – that was what I kept telling myself anyway. Telling myself was one thing, believing myself another.

The picture above my bed was, for me, no longer of my Joan of Arc, but of Marie Duval. It was too painful a reminder. I took it down and put it in the back of my cupboard. Out of sight, out of mind, I thought. I wasn’t angry at Marie. She had been kindness itself. Not a bit of it. I was angry at Joan. I felt she had misled me, abandoned me; and, talking to the cupboard one night, I told her so.

The river, the only place I could be alone and away from it all, had now become my place of tears. The faithful Jaquot was always there, always waiting for me. Every day now, after school, I would go and sit on the river bank and cry until I had no more tears left to cry. I poured my heart out to Jaquot, and he stayed and listened – providing I kept feeding him.

As May 8th came closer, Marie was ever more fêted at school, and preparations for the great day were becoming increasingly evident not just at school, but throughout the city – bunting everywhere, flags in the streets, and images of Joan of Arc in every shop window. There were reminders around me everywhere I looked. Worst of all was having to smile through it all at school, having to hide my misery. With Jaquot I didn’t need to hide anything.

On the night of May 6th I made the decision. I would simply miss school the next day. I would go down to the river and spend all day there with Jaquot. I went off to school at half-past seven as usual and made quite sure I was out of sight of the house before I doubled back and made for the river. Jaquot wasn’t there, but then I was early, earlier than I’d ever been before. He came soon enough though, hopping up on to the toe of my shoe to ask for his breakfast. I fed him and told him what I’d done and why I’d done it. I had the distinct impression he didn’t approve.

“Be like that, then,” I said, and I lay back in the sun and closed my eyes, soaking myself in the warmth of it. For a while I could hear Jaquot pecking busily around my feet. But when I opened my eyes again he was gone, and nowhere to be seen.

That was when I saw the light, a glowing light as bright as the sun, in among the branches of the trees above me. Then it was brighter still, and whiter, enveloping me utterly, until there was nothing to see except the light, and nothing to be heard either. The city had hushed to silence all around me.

The voice came from deep inside the light, deep inside the silence, from far away and close by. “Talking of sparrows,” it said, “there was only one creature on this earth who really knew Joan. She called him Belami. He was a sparrow, just an ordinary sparrow like Jaquot; and he stayed with her all her life, almost from the very beginning, and right to the very end. He was her best friend on this earth, maybe her only friend, too. I could tell you more, if you’d like it. I could tell you her whole story, and Belami’s too. Would you like that?”

I didn’t say yes. I didn’t say no. Because I couldn’t say a word.

“I’ll tell you anyway,” came the voice again, “because I want to, and because I think you should know all of it, as it was, as it happened.”

I felt myself drifting into the light, into the voice.