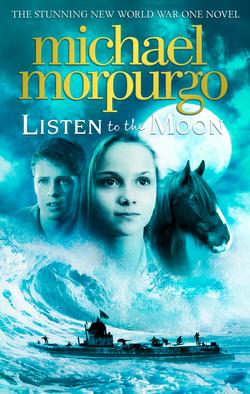

Читать книгу Listen to the Moon - Michael Morpurgo, Michael Morpurgo - Страница 11

Оглавление

LUCY’S MYSTERIOUS APPEARANCE FROM OUT of nowhere had been the talk of the islands for weeks now, eclipsing even the news of the war from over in France and Belgium, which had been the main anxiety and preoccupation of just about everyone in the islands since the outbreak of war nearly a year before – every islander except Uncle Billy, that is, who lived his life in another world altogether, seemingly quite oblivious to the real world around him.

All the news they read in the newspapers, or picked up from any passing sailors coming into port at St Mary’s, dashed again and again their hopes of an early peace, and confirmed their worst fears. To begin with, the papers had been full of patriotic fervour and cheery optimism, every headline another rallying cry to the nation. But in recent months much of that had vanished, as they read yet more news of losses, of ‘heroic stands’, and ‘bravely fought’ battles in Belgium, or ‘strategic’ retreats in France. Armies that were going backwards and losing men by the thousands were clearly not winning – as some newspapers were still trying to insist – and most people knew it by now. None of the boys was going to be home by Christmas time, as everyone had hoped, that was for sure.

The islanders were doing their best to put a brave face on it. They tried all they could to keep the home fires burning with hope, but nothing any longer could hide the truth behind the daily reports of ever mounting casualties, those dreadful long lists in the papers of the killed, the wounded and the missing in action. And in recent months there had been four drowned sailors from Royal Navy ships washed up on the shores of Scilly, every one of them a stark reminder that the war at sea was not going well either.

These were islands accustomed enough to tragedy. ‘Lost at sea’ had always been a common enough cause here of sudden disappearance and death, as witnessed on monuments in churches all over the islands. But when the news came in that the islands had suffered their first losses of the war – two young lads whom everyone knew, Martin Dowd and Henry Hibbert – a pall of grief settled over everyone. Both had rowed in the St Mary’s gig, and both had been killed near Mons on the same day. They were Scillonians. They were family. The war had truly come home.

But it was what had happened shortly afterwards to young Jack Brody that was the most difficult to bear, particularly for the people of Bryher. He was known throughout the islands as a cheeky, cheery sort of a fellow, a bit of a show-off, the life and soul of any get-together, always boisterous and full of fun. He had joined up at sixteen – under age – the first to volunteer from the islands, full of his usual bravado and banter, bragging how, once he got out to France, he’d sort out Fritz soon enough. A couple of years older than Alfie, Jack had been his hero all the way through school, always in and out of trouble, champion at boxing, and the best footballer in the whole school without any question. He was everything Alfie admired, everything he wanted to grow up to be.

But now, only six months after going off to war, he was back home again. From time to time Alfie would see him around the island, sometimes being pushed in his wheelchair along the path by his mother, sometimes limping on crutches, a couple of medals pinned to his jacket, his left leg missing. Jack could still put a brave face on it. He’d wave wildly at anyone and everyone he saw. Miraculously, despite his destroyed mind and mangled body, the heart of him still seemed to be there. Whenever he saw Alfie, he’d call out to him, but he didn’t know any more who Alfie was. Alfie dreaded meeting him. Jack’s speech would be garbled, his head rolling uncontrollably, his mouth slack and dribbling, one eye dull and blinded. But it was the tucked-up trouser leg that Alfie could not bear to look at.

Alfie hated himself for doing it, but once or twice he had even hidden himself behind some escallonia hedge when he’d seen Jack coming, just to avoid having to meet him. Sometimes though, there was no way out, and he’d have to force himself to go over and say hello to him, to confront again the leg that wasn’t there, the livid scar across Jack’s forehead where the shrapnel had gone in, and where, as his mother told him every time they met, it was still lodged deep in his brain. “How are you today, Jack?” he’d say. And Jack would try to tell him, but the words came out as scrambled as his mind. He would keep on trying, desperate to communicate. Humiliated, frustrated and angry, Jack would often have to turn away to hide his tears, and then there seemed nothing else to do but to leave him. It shamed Alfie every time he did it.

So during that summer, for Alfie, as for so many, the finding of ‘Lucy Lost’ – as she was now known all over the islands – had been a welcome distraction. She took everyone’s mind off poor Jack Brody, and the loss of Martin and Henry. The overwhelming shadow of the war itself receded. Lucy Lost gave them all something else, something new, to talk about. Speculation was rife. Imagination ran riot. Rumours were everywhere – plausible, or implausible, it made no difference. Stories and theories abounded, anything that might possibly explain how Lucy Lost had turned up alone and abandoned on St Helen’s, with nothing but an old grey blanket and a raggedy teddy bear with one eye and a gentle smile.

How had she got there? How long had she been there? And who on earth was she anyway? Everyone wanted to know more about her, and if possible to catch a glimpse of her. A few of the most inquisitive had even gone so far as to take a trip over to St Helen’s to scour the Pest House and the island for any telltale clues. They had found nothing. All anyone knew for sure was that her name was Lucy, that this was the only word the strange little girl had ever uttered, and that Big Dave Bishop had discovered the teddy bear and the blanket in the Pest House – both presumably hers. Big Dave had talked a lot about his discovery – but, true to his word, had made no mention of the name embroidered on it. There was so little to go on. But what the islanders didn’t know about Lucy Lost, they more than made up for by invention.

The stories became more and more fantastical. It was said that Lucy was deaf and dumb, and so she had to be “a bit mazed in the head”, like Uncle Billy. Just as he was ‘Silly Billy’ to some, so she was ‘Loony Lucy’. Others thought her mother must have died in childbirth, that she had been marooned on St Helen’s, deliberately abandoned there by a cruel father who had tired of providing for her.

There were other stories going round too, that she was the child of one of those unfortunates who had been quarantined in the Pest House on the island centuries before, that she had perished there long ago, and ever since had wandered the island, a lost soul, a ghost child. Or maybe, it was said, Lucy Lost had fallen overboard from some ship in the Atlantic and had been saved from drowning by a passing whale and carried safely to shore. It could happen, some argued. Hadn’t Jonah himself been saved just like that in the Bible? And hadn’t the Reverend Morrison only recently preached a sermon about Jonah in Bryher Church, telling everyone that these stories from the Bible weren’t just stories, that they were the truth, the word of God himself, God’s truth?

Then, most fantastical of all perhaps, and certainly the most popular theory of all, there was the mermaid yarn – Alfie had heard it often enough in the schoolyard. Lucy Lost was really a mermaid, and not just any mermaid, but the famous Mermaid of Zennor, who had swum over to the Scilly Isles from the Cornish coast many years ago, who had come up out of the sea on to St Helen’s, and sat on the shore there and sung sweet songs to passing sailors and fishermen, to tempt them on to the rocks, combing her hair languorously as mermaids do. But she had grown legs – mermaids can do that, some said, like tadpoles. Doesn’t a tadpole grow legs out of a wiggly tail every spring? All right, so they might not sing songs or comb their hair, but they grow legs, don’t they? All these stories were so unlikely as to be ridiculous, laughable, and quite simply impossible. It didn’t matter. They were all fascinating and entertaining, which was probably why the mystery of Lucy Lost remained the talk of the islands for weeks and months that summer.

Most of the islanders did realise, of course, when they really thought about it, that there had to be some more rational, sensible explanation as to why and how Lucy Lost had been marooned on St Helen’s, how someone so young could have survived. They all knew that if anyone had any idea of the truth of all this then it would very likely be Jim Wheatcroft or Alfie, who had found her in the first place, or Mary Wheatcroft who was looking after her at Veronica Farm on Bryher. Surely they would know. Maybe they did know. They were certainly being overly secretive about her and protective, as they always had been about Silly Billy, ever since Mary had brought him back from the hospital. They all knew better than to ask questions about Silly Billy – he was family after all – that Mary would snap their heads off if they dared. But Lucy Lost, they thought, wasn’t family. She was simply a mystery, which was why, wherever any of the family went, they were liable to be badgered by endless questions and opinions from anyone they met.

Mary was able, for the most part, to keep herself to herself, to avoid too much of this intrusion into their lives, staying inside the farmhouse and around the farm as much as possible. But she did have to leave Lucy alone in the house, and venture off the farm at least twice a day to visit Uncle Billy to bring him his food, and tidy up around him as best she could. She’d find him in the boathouse, in the sail loft above, or more often these days out on Green Bay itself, on the Hispaniola, but always working away.

She’d been bringing him his food, seeing to his washing, cleaning around him, looking after him, for five years or more now. She’d done this every day without fail, ever since she’d brought him home from the hospital in Bodmin, from the County Asylum, or the ‘madhouse’, as everyone called it. It was on her way to and from Green Bay to see to Uncle Billy that more often than not she’d meet one or two of her neighbours on the beach. Some, she knew, had been deliberately loitering there with intent to ambush her, and, whoever it was, sooner or later they would begin to ply her with questions about Lucy Lost. It hadn’t escaped her notice that before the coming of Lucy she had hardly ever met anyone on her way to or from Uncle Billy. She fended them all off.

“She’s fine,” she’d say, “getting better all the time. Fine.”

But Lucy wasn’t fine. Her cough may not have been as rasping, nor as repetitive and frequent as before, but at night-times in particular it still plagued her. And sometimes they could hear her moaning to herself – Alfie said it was more like a tune she was humming. But moaning or humming, it was a sound filled with sadness. Mary would lie awake, listening to her, worrying. Night by night lack of sleep was bringing her to the edge of exhaustion. She gave short shrift to anyone who turned up at the door ‘just visiting’, but quite obviously trying to catch a glimpse of Lucy. Her frosty reception seemed in the end to be enough to deter even the most persistent of snoopers.

It fell to Jim much more often to confront the endless inquisitiveness about Lucy Lost. Like it or not, he had to mend his nets and his crab pots down on Green Bay, where all the fishermen on the island always gathered together to do the same thing when the weather was right. He had to see to his potatoes and his flowers in the fields. He had to fetch seaweed from the beaches for fertiliser, and to gather driftwood there for winter fires. Wherever he went, whatever he was doing, there were always people coming and going, friends, relations, and they all pestered him about Lucy Lost at every possible opportunity.

If Jim was honest with himself, he had at first quite enjoyed the limelight. He had been there with Alfie, when Lucy Lost was first discovered. They had brought her home. All the attention and admiration had not been unwelcome, at first. But after a week or two he was already tiring of it. There were so many questions, usually the same ones, and the same old quips and jokes bellowed out across the fields, or over the water from passing fishing boats.

“Caught any more mermaids today, have you, Jim?” He tried to laugh them off, to remain good-humoured about it all, but he was finding that harder by the day. And he was becoming ever more concerned about Mary. She was looking tired out these days, and not her usual spirited self at all. He’d tried to suggest, gently, that she might be taking on too much with Lucy Lost, that surely she had enough to do caring for Uncle Billy, that maybe they should think again about Lucy, and find someone else to look after her. But she wouldn’t hear of it.

Alfie too, as time passed, was being given more and more of a hard time over Lucy Lost. Every day at school, he found himself being quizzed, by teachers and children alike, and teased too.

“How old is she, Alfie?”

“What’s she look like?”

“Your mermaid, Alf, has she got scales on her instead of skin? Has she got a fish face? Green all over, Alfie, is she?”

Zebediah Bishop, Cousin Dave’s son, who took after his father and was the laddish loudmouth of the school, had always known better than most how to rile Alfie. “Is your mermaid pretty then, Alfie boy? Is she your girlfriend, eh? You done kissing with her yet? What’s it like kissing a mermaid? Slippery, I shouldn’t wonder!” Alfie did try his utmost to ignore him, but that was easier said than done.

One morning, as they were lining up in the schoolyard on Tresco to go into school, Zeb started up again. He was holding his nose and making faces. “Cor,” he said, “there’s something round ’ere that stinks awful, like fish. Could be a mermaid, I reckon. They stink just the same as fish, that’s what I heard.”

Alfie had had enough. He went for him, which was how they ended up rolling around on the ground, arms and legs flailing, kicking and punching each other, till Mr Beagley the headmaster came out, hauled them to their feet by their collars and dragged them inside. The two of them ended up in detention for that all through afternoon playtime. They had to write out a hundred times, “Words are wise, fists are foolish.”

They were not supposed to talk in detention – you got the ruler if Beastly Beagley caught you – but Zeb talked. He leaned over and whispered to Alfie: “My dad says your mermaid’s got a little teddy bear. Ain’t that sweet? Alfie’s got a girlfriend who’s got a little teddy bear, and who’s so dumb she don’t even speak. She don’t even know who she is, do she? Doolally, mad, off her ruddy rocker, like your daft old uncle, like Silly Billy, that’s what I heard. He should’ve stayed in the madhouse where he belonged, that’s what my ma says. And that’s where your little girlfriend should go, and take her teddy bear with her. Not all there in the head, is she? And I heard something else too, a little secret my dad told me, about her blanket, the one my dad found on that island. I know all about it, don’t I? She’s German, she’s a Fritzy, your smelly girlfriend, isn’t she?”

Alfie was on his feet in a flash, grabbing Zeb and pinning him against the wall, shouting in his face, nose to nose. “Your dad promised he wouldn’t tell. He promised. If you say anything about that blanket, then it’ll make your dad a big fat liar, and I’ll—”

Alfie never finished because that was the moment when Mr Beagley came storming in, and pulled them apart. He gave each of them six of the best with the edge of the ruler, on their knuckles this time. There was nothing in the world that hurt more than that. Neither Alfie nor Zeb could stop themselves from crying. They were stood in the corner all through last lesson after that. Alfie stared sullenly at the knots in the wood panelling in front of his face, trying to forget the shooting pain in his knuckles, fighting to hold back the tears. The two dark knots looked back at him, a pair of deep brown eyes.

Lucy has eyes like that, he thought. Eyes that look into you, unblinking, eyes that tell you nothing. Empty eyes.