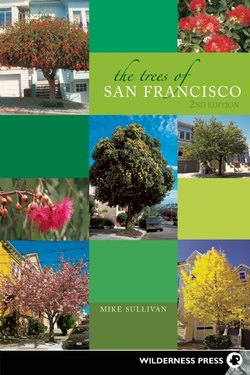

Читать книгу The Trees of San Francisco - Michael Sullivan - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеMary Ellen Pleasant and Her Blue Gums

MARY Ellen Pleasant, an African American woman often called California’s “Mother of Civil Rights,” planted the row of mature blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus) at 1661 Octavia Street, near Bush Street, in Pacific Heights. Though born a slave in 1817, she came to own a sprawling 30-room estate at this address, which has been called the western terminus of the Underground Railway that helped to usher fugitive slaves to freedom in pre–Civil War times.

In fact, once freed herself, Pleasant spent many of her early years helping fugitive slaves escape the American South. Pursued by the law, she headed to gold rush San Francisco in 1852, where with her business acumen she parlayed an inheritance from her first husband into a small fortune. She used her wealth to continue supporting African American rights. In 1868, long before the civil rights battles of the next century, Pleasant brought a lawsuit against two San Francisco streetcar lines that had denied her the right to ride because of her race. Her suit ultimately went to the California Supreme Court, where she won the right for all African Americans to ride the streetcars.

Later in life, Pleasant suffered tabloid-driven scandals and financial reverses. She died in San Francisco in 1904 and is buried in Tulocay Cemetery, north of the city, in the town of Napa. All that is left of her opulent mansion is the row of blue gum eucalyptus she planted in front of her property on Octavia Street. Set in the sidewalk amid these trees, a historical marker identifies the blue gums as something special—a part of San Francisco’s history.

Eucalyptus globulus

BLUE GUM EUCALYPTUS

LOCATION: Main Post of the San Francisco Presidio (this Centennial Tree was planted in 1876 by the U.S. Army to celebrate the country’s 100th year)

Native to a small range in Tasmania and southeastern Australia, the blue gum is likely the most common nonnative tree in California. Introduced to California in 1856, the fast-growing tree was planted extensively by pioneers hoping to make a fast buck from timber plantations (a mistake, as it turned out, because the wood of the blue gum is not well suited for sawn timber). The blue gum has since naturalized and become common in California—too common for some native-plant enthusiasts, who push for its eradication. Others (myself included) are not so doctrinaire; I associate eucalyptus with California and could not imagine the state without them.

The blue gum is one of our largest trees: its towering crown can reach 150–200 feet in ideal conditions, and in its native Tasmania, the tree is known to reach 300 feet. The leaves of blue gums undergo an interesting change in shape as trees mature. The waxy juvenile leaves produced in the tree’s early years are silvery blue and rounded, occurring in opposite pairs on the branch. The deep green adult leaves are sickle shaped, thick, and leathery, and they hang vertically from the tree’s branches. This makes them perfectly adapted to the California coast’s dry but foggy summers. The leathery leaves retain moisture, and their vertical sickle shape causes the condensing fog to drip onto the ground, delivering moisture to the tree’s roots.

Blue gums are a major source of eucalyptus oil, which has disinfecting properties and is used in a number of products. The oil is extracted from the twigs and leaves of the tree. A row of mature blue gums on Octavia Street in Pacific Heights has an interesting San Francisco history; see “Mary Ellen Pleasant and Her Blue Gums” on the previous page.

Schinus terebinthifolius

BRAZILIAN PEPPER

The Brazilian pepper is a fastgrowing, vigorous evergreen tree that is well adapted to city conditions. It has glossy, dark green compound leaves composed of 5–13 leaflets, forming a rounded crown resembling that of a carob tree. The female trees (infrequently planted on city streets) produce clusters of red berries, often used in Christmas wreaths. A shrub by nature, this tree does not develop a single straight trunk unless trained to do so—many examples of “crazy straw” Brazilian peppers are found where the trees have enjoyed only intermittent care. Attention should also be paid to their canopies, which need thinning to reduce risk of breakage in winter storms, since, like many fast-growing trees, Brazilian peppers have brittle wood. Native to southeastern Brazil and northern Argentina, the Brazilian pepper has become an invasive pest in many semitropical areas. In southern Florida, it covers some 700,000 acres, and the tree cannot be legally sold or imported in Florida or Texas.

LOCATION: 832 Alvarado St./Hoffman Ave. in Noe Valley; many examples on Cabrillo St. between Arguello Blvd. and 3rd Ave. in the Richmond

Lophostemon confertus

BRISBANE BOX

LOCATION: 960–970 Haight St./Divisadero St. in the Haight-Ashbury; also 696 2nd Ave./Cabrillo St. in the Richmond

In recent years the Brisbane box has become one of the most commonly planted trees in San Francisco, and in particular it has become the favorite of the city’s Department of Public Works. It has a lot to like: attractive, dark evergreen foliage in a distinctive treelike, upright oval form; smooth, reddish-brown peeling bark reminiscent of California’s madrone trees; resistance to pests and diseases; and tolerance of wind, fog, dry summers, sidewalks, and poor soil. It is also a very low-maintenance tree—easy to prune, with no significant leaf drop, and for a large tree (it can easily reach 40 feet), it is relatively kind to sidewalks. Some people find this tree a bit dull, because its white flowers are nothing to write home about when they bloom in July and August and have no olfactory charm.

Dull it may be, but reliability counts for something in San Francisco’s harsh (for trees) urban environment, which explains the Brisbane box’s increasing popularity on city streets, as the seventh most frequently planted tree in San Francisco. Native to the forests of eastern Australia, the Brisbane box is also a common street tree in Sydney, Melbourne, and other cities Down Under.

Eriobotrya deflexa

BRONZE LOQUAT

LOCATION: Northeast corner of Frederick St. and Stanyan St. in Cole Valley; also at 316 Moraga St./9th Ave. in the Sunset

Bronze loquats are recognizable by the coppery bronze color of their new foliage, which eventually fades to green, giving the trees an attractive two-tone appearance for much of the year. The tree, which grows to 25–30 feet, has creamy white flower clusters March–May, but it often does not bear fruit. A related loquat, Eriobotrya japonica, is also found in the Bay Area (but more often in backyards) and bears edible, orangeyellow fruit 1–2 inches in length. The bronze loquat is native to Taiwan; its edible relative is from China and southern Japan. All loquats are from the rose family (Rosaceae ), which includes apples and pears, and a close examination of loquat fruits will show the resemblance to their more popular relatives.

Araucaria bidwillii

BUNYA-BUNYA

Like its close relative the Norfolk Island pine, the bunya-bunya has a distinctive silhouette. As with other members of the ancient Araucaria genus, the tree’s branches are spaced evenly along the trunk in whorls, giving the tree a symmetrical look. Bunya-bunyas are large trees, often reaching 80 feet, and mature trees develop a characteristic rounded crown. The glossy green leaves are lance shaped, sharply pointed, and spirally arranged on branches. The tree is native to the Bunya Mountains of Queensland in northeastern Australia.

Perhaps the most unusual feature of the bunya-bunya is its football-sized female cone, which looks something like a pineapple and can weigh 10–15 pounds (the record is held by a 17-pounder). The cones, which set every three years, are produced high in the tree’s canopy and can cause serious injury when they fall. Each cone produces 50–100 large edible seeds, or bunya nuts. The nuts were a food source for Queensland’s aborigines.

LOCATION: 201 Vicente St./Wawona St. in West Portal. This is one of the most spectacular trees in San Francisco, and a rare tree in the city. Also at 1818 California St./Franklin St. in Pacific Heights; a grove of five trees in the park at the corner of Hyde St. and Jefferson St. in Fisherman’s Wharf; and in front of Chez Panisse restaurant at 1517 Shattuck Ave. in Berkeley.

When the cones set, the aborigines put aside their tribal differences and feasted. They headed for the Bunya Mountains, where each tribe owned particular trees. (Visitors to Bunya Mountains National Park can still see the notches carved into the trees to facilitate climbing for the harvest.)

Bunya nuts, a delicacy in Australia, are still eaten today. They can be eaten raw or roasted, and the nuts’ flour can be used to make breads and cakes.