Читать книгу The Driving Force - Michel Tremblay - Страница 7

ACT ONE

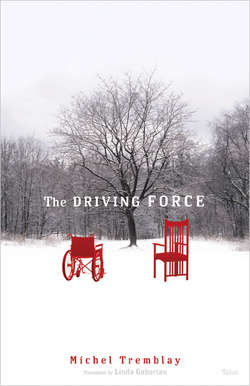

ОглавлениеALEX’s room in a home for Alzeimer’s patients.

ALEX is sitting in a wheelchair.

CLAUDE, his son, has just finished washing and dressing him and is patting his cheeks with eau de cologne.

ALEX will remain perfectly still, absent, during the entire act.

CLAUDE

You don’t know what this takes out of me, do you? The physical effort … and all the rest … Washing you. Powdering you. Putting on your diaper, your clean pyjamas. Shaving you. Patting your cheeks with cologne. Just to cover up how you’re going to smell in half an hour. So it won’t stink the minute we open the door. To create the illusion that you’re clean for a while.

He has finished grooming his father. He backs away from the chair and examines his work.

How long’s it going to take before you start deteriorating again? Your brain has practically stopped working, but your heart goes on pumping like nothing was wrong. You always had a thick head of hair, and a heavy beard. If I weren’t here to shave you … They don’t have the time around here, do they? I mean, they can’t doll you up like I do, they can’t devote the whole afternoon to you, they make it short and sweet, deal with the most pressing stuff, the most urgent, they’ve got other cases, worse cases, the bedridden ones who can’t be moved … They don’t have time to climb into the tub with you to give you more than a sponge bath … They’ll oil your body every night so you don’t get bedsores, but they won’t climb into the tub with you to give you a bath ...

He leans over his father.

When that happens to you, when they can’t move you anymore, when that time comes and you can’t get out of your bed, I promise I’ll go on shaving you. And patting your cheeks with cologne.

Silence.

It’s called dignity.

Silence.

What are you thinking about? You must be thinking about something? I don’t see how someone can stop thinking. Completely. Are you really not aware of anything? Not so long ago, you used to look at me with, I don’t know, let’s say a trace of intensity. You followed me around the room with your eyes. You didn’t know who I was, but I was there, you saw me, and your eyes followed me. Now when I walk by you, you don’t even blink. You look like an old, grouchy baby. Are you blind? Has your brain stopped sending messages to your eyes? Has it stopped telling your eyes that they should close once in a while, to lubricate them? When we put those drops in your eyes, can you feel them overflow and run down your cheeks? No, you can’t, right? We have to wipe them to prevent them from running into your mouth because they could be poisonous. There’s lead in eyedrops, and lead is dangerous. Think about it, when I was starting out, when I was a linotypist, I was the one who was facing lead poisoning. And now I’m putting lead in your eyes. I don’t know how many gallons it would take for your body to finally react … for your heart to stop, or explode … But that would mean you’d have to have one. And it’s too late for that, right? Today’s not the day you’re going to start having a heart … Actually, we can’t even say it’s too late. No. There was never a time for that. And even if you’d had a heart as big as the world, what would that change now? Right now, today, between the two of us? You’d still be in the same place. And so would I. I’d still come and do exactly the same things. We’d still be staring at each other, you in your diaper you’ve probably already started to dirty, and me, barely dry after our bath together. The only thing that would be different is our past. Our memories. But since you wouldn’t have any memories, because you’d be in the same state, it wouldn’t change a thing for you. Nothing would be different for you today, if you had been a devoted, loving father, so why weren’t you? It wouldn’t change a thing!

He moves away, goes to sit on the edge of his father’s bed.

This afternoon, on my way here, I had some errands to do, I had to buy myself a pair of shoes, and at one point, I walked by Ogilvy’s. It’s weird how things happen, sometimes … Without thinking twice, really, I swear I didn’t think about it, otherwise I would’ve felt stupid and I wouldn’t have done it, but really, without thinking, I walked into Ogilvy’s and headed straight for the perfume counter. Never saw so much perfume! The place smelled of wealthy women, like intermission at Place des Arts. Everything was shiny and chic, with glass and mirrors everywhere … They say our sense of smell triggers our memories best, so … I wanted to try even though I figured it was impossible … Anyway, I pounced on the first saleslady I saw, a pretty lady of a certain age, well-dressed, well-groomed, all neat and clean, with a big smile on her face because she probably figured she’d be sure to sell some expensive perfume to the middle-aged man who was heading toward her … for his pretty secretary, or his mistress, or maybe for his actual wife if he was as straightlaced as he looked … She didn’t recognize me. Guess she never goes to the theatre. I went right up to her and without thinking, I swear, I asked her, “Does Lotus by Yardley still exist?” Honestly … I didn’t even know if the Yardley company still existed! And you know what she said? “Even if it still existed, I doubt that we’d sell it here, sir. I think they used to sell it in drugstores.” Is that true? I know, I can remember clearly that we bought yours at the drugstore, but is it true they didn’t sell it anywhere else? One thing’s for sure, it was pretty cheap. Every year, Ma would give me seventy-five cents and say, “It’s your father’s birthday next week, go buy him his bottle of Lotus by Yardley.” Seventy-five cents plus tax. That’s what your birthday present cost us. And it wasn’t even me who paid for it. I’d ask them to gift-wrap it … always the same drugstore paper with the little blue and gold flowers on a white background … When I gave it to you, you’d always say the same thing, “Thanks, my boy! Exactly what I needed, hardly have any left! I was trying to make it last as long as I could. When an elastic band snaps in your face, you know you gotta throw it out, but you think you can make perfume last forever … but sooner or later, the bottle’s empty and you’re stuck smelling your own smell! And in my profession, kid, you’re better off not smelling natural, better to smell like flowers, a bouquet of roses, like a whole rose garden! A travelling salesman is more than a bee flying from flower to flower, he’s a bee that brings flowers to flowers.” And you’d douse yourself with the stuff. You put it on your handkerchiefs, your shirt collars and cuffs … Behind your back, Ma always said you used so much of it, when you came out of the bathroom, sometimes the air was so thick you could cut it with a knife. And she was almost right! I’m telling you, we could smell you coming from way off. In your car, in the winter, we’d suffocate, it smelled so strong. Sometimes I’d walk by your bedroom and say to myself, “I guess he’s back,” because I could smell you. But most of the time, it was just a faint whiff, a trace Ma hadn’t managed to get rid of, a smell that wouldn’t go away … A couple of times I heard her say, on the phone, “Alex smells like a funeral parlour! And it’s our own fault.” And … this afternoon … that’s what I was looking for. That smell. I can’t remember it. At all. I couldn’t tell you what it smelled like, I just remember it smelled strong. What does a real lotus flower smell like? Maybe I could’ve gone to a florist’s, but I don’t know if they sell them. This time of the year, or any time. And I wanted to see if what they say about our sense of smell is true, not with real flowers but with my memory of Lotus by Yardley. Not the real smell, I forgot that ages ago, but … Maybe opening the bottle, just now, after shaving you, things would’ve come back to me all of a sudden ...

He comes back to his father’s wheelchair and crouches down beside him.

Because I want you to know that I stopped hating you recently. And I was hoping that Lotus by Yardley would jump-start my motor again. Because I feel numb when I’m with you now. I don’t feel a thing when I look at you, and I miss those first times when we were in the tub together and I wanted to drown you. I’m getting close to forgiving you, and that makes my head spin. Because I don’t want to. Because that’s the last thing I want. Not as long as you’re still alive!

He moves away from his father.

When Mariette came to set you up here, I hadn’t seen either one of you for ages. I hadn’t even been in touch with you for a long time. I’d decided to forget I ever had a father, and as for my sister, she’s such an incurable nighthawk, I never know when to call her … Listen to me … as if that were any reason to lose touch with your sister … It sounds like one of our old family myths … the incident is true, but there’s so much icing on it, no way you can find the truth. I didn’t see the two of you anymore because I didn’t feel like seeing you, period! The last time I saw you was at Ma’s funeral. And I said to myself, “Never again! Never!” You dared go to her funeral, acting like a grief-stricken widower, after spending your life practically laughing in her face, after cheating on her, humiliating her, treating her like your servant who kept your slippers warm while the master went out to play! They made us sit together on the same bench in the church, even though I didn’t want to—I was sitting on your left, and Mariette on your right. When you started crying, heaving your shoulders, I thought you were laughing, that you’d finally let the cat out of the bag, that you were unable to hide your relief at being free, at last, after all those years in the prison your family had represented to you … But no, you were crying, you were sobbing like a loving husband. You kept it up for the whole ceremony. You were still mocking her in her coffin. Shameless, sure you’d never be punished, sure you’d come out on top as usual! Even the relatives who never liked you were touched. Poor Alex has lost his Madeleine, he loved her so much. I felt like standing up and exposing you right there in the middle of the church. But it wasn’t the right time or place, it was the funeral of the most important person in my life, so I decided to spare you. But I also decided I’d never lay eyes on you again. And I kept my word. Anyway, I admit it was a shock when I saw you again after all those years. Mariette had warned me, but … nothing can prepare you for this kind of thing. You tell yourself: it won’t be that bad, I’ll get through it. I wanted to visit you while you were still conscious. Just in case. In case, something might happen. But what happened wasn’t what I expected … You were already suffering from aphasia. Not only had I never seen someone suffering from aphasia, but it was happening to my father who’d spent his life holding forth, delivering his endless speeches, drowning us, and the truth, in a flow of words, a dense logorrhoea fuelled by alcohol and the desire to trick people, to get his own way. You could hardly manage to say a few words, you had to concentrate, we could see in your eyes how hard it was, and then, instead of the word, “hello,” for instance, you’d come out with the word “helper” or the word “jello” … When I came into this room, you were expecting me, Mariette told you I was coming. You stood up beside your bed, you looked me straight in the eye, you concentrated, I could feel the muscles around your mouth straining, and you said, “Jello!” It was pathetic, it was devastating, I felt like I’d been hit with a ton of bricks, for sure, but at the same time … At the same time, I couldn’t help but think it was a strange twist of fate, almost poetic justice, that the great sweet-talker, the big gabber, the king of eloquence couldn’t even find the words to say hello! I spent, I don’t know how long, maybe two hours, with you that day. And you didn’t manage to say ten sentences. I could read the humiliation on your face because you still had periods when you were completely conscious, totally aware, and you were mortified to have me see you in that state … I told you to talk with your hands, that I realized you were having trouble pronouncing words, and that only made you feel more embarrassed. Then, at a certain point, during a silence that lasted too long, I could see in your eyes that you thought I was happy to see you like that, and that I was staying here so I could enjoy your humiliation, as if the thought that crossed my mind when I arrived had stayed with me, and I wasn’t leaving because I was happy you were aphasic. And you know what? I found that so outrageous, I didn’t even bother to contradict you, or to defend myself. I thought, “If he’s dumb enough to think that, let him think it.” But maybe I was kidding myself? What do you think? Were you the one who was right, in the end? Did you see something in me that I’d censored the minute I thought it, because I found it too ugly? Were those first two hours the nightmare I remember today, or have I just buried the pleasure I felt under the layer of pain, the layer of sadness a good son is supposed to feel under the circumstances? We’ll never know, will we? Because it’s too late for you—and I’d never dare face something like that. Even if I find myself doing things I never would’ve imagined I could do since I started coming here regularly. Some nice things people might say are due to a natural generosity, and other things … like what’s going on right now, and every time I come to visit … talking like this, rattling on to a dying man who’s lost his mind, paying him back, day after day, for his pointless speeches, with more pointless speeches, talk, talk, talking, till I drop, to an inert body, with no hope of remission, on your side or mine, because one of the two parties has withdrawn permanently. I’m exhausted when I leave here, my throat is raw, my nerves are shot, because I dare say out loud things I’d never dare write in my plays because I’d find them either too melodramatic, or too dull! I write crazy, badly constructed, wildly lyrical plays for you, three afternoons a week, and you can’t even appreciate them or dismiss them with a wave of your hand and a sarcastic grin, the way you did with everything I’ve ever written. I make you listen to talk you would’ve hated, but in the final analysis, I’m punishing myself because I know you’re in no state to accept it or reject it. But, at the same time, it’s become my new motor! My punishment has become my driving force! Instead of talking to you in my head, the way I did for most of my life, I can do it for real now, even if I know that I’ll never be able to convince you of anything! I’ll never convince you that I’m talented or that what I write is any good! All my life I’ve tried to avoid writing to please the critics or the experts, I’ve just focussed on the play I had to write, concentrated on what I thought I had to say, and refused to think about what so-and-so might say about this sentence or that speech … but all along I knew I was kidding myself, that there was always one person I wanted to please, one person I needed to convince, like when I wrote my very first play … You committed the most violent act I’ve ever seen anyone commit— you destroyed the only manuscript of an author’s first play. You burned my first play, page by page, with your lighter, with no scruples, no regrets, with the clear conscience of a man who’s convinced he’s right! You destroyed my play because you were convinced you were right, just like I was convinced I was right to denounce you in my play. I could have rewritten it, I knew it by heart, it was a short play, probably not very good, but I chose to drop it, and to keep that blow intact, like a burn that never heals, and over the years I realized that it had become my motor. I’d never be able to forgive you for committing that act, and as long as forgiveness was impossible, I’d have a reason to write. I wanted every play I wrote, every bit of my work, every successful production to be a blow to you, as painful, as brutal as the one you dealt me before my career had even begun. You wanted to crush me in the bud, you failed, and now I was going to try to crush you, slowly but surely, bit by bit, success after success after success! I had my first taste of revenge ten years ago, do you remember? No, even if your brain was still working you wouldn’t remember, because you were so caught up in your little triumph, so intoxicated by your fifteen minutes of fame that you didn’t notice a thing. There was a TV show back then where five nights in a row, they’d invite a celebrity to come meet people from his past—relatives, teachers, classmates … When my turn came, when they invited me, I saw an opportunity to stage a double-revenge, and I succeeded.